| 5. Bratislava Sered | ||

|

My main experience of my 18-month stay in Bratislava was living with my two brothers. Both of them, as well as their friends who frequented our home, always surrounded me with much love. Józsi (Joseph) was 20 and Erno (Ernest) 18, when I joined them as third resident in their sublet room. I didn’t find myself among strangers, a situation that greatly eased my homesickness. Nevertheless, I often thought about my parents and younger sisters I had left at home. My brothers had spent several years at Rabbi Eckstein’s Yeshiva in Sered, before leaving for Bratislava. (Our father had chosen this Yeshiva of many others in Slovakia. I am going to discuss the advantages of this extraordinary institute later) There they befriended several students, who had already attained their PhD in rabbinical seminars but needed further study to be able to serve as rabbis. These scholars wanted to act as Orthodox rabbis and felt that they needed to broaden their Talmudic knowledge. Since both my brothers were excellent Yeshiva students, these scholars sought their help with Talmud and Judaica lessons. Neither of them is still living, hence I feel at liberty to divulge their names: Dr. Jeno (Yaakov) Duschinski from Rákospalota, who later became Chief Rabbi of South Africa, and Dr. Leo Singer from Rimaszombat (Rimavská Sobota), who was murdered in Auschwitz. As both of them continued their studies at the High Yeshiva of Bratislava, with my brothers, they naturally were frequent visitors in our sublet room. I learned much from them and enjoyed their brotherly love and benevolent teasing. It may well have been the general secular education of those friends that motivated my brothers to reach beyond their expected rabbinic ordination into other disciplines as well. They started to bring home secular textbooks and studied them feverishly with the aim of a high school diploma. It was essential that the Yeshiva authorities get no wind of this activity; lest the “heretics” would be expelled from the school. Yeshiva supervisors used to make surprise visits at the homes of the students to sniff out any “unholy” literature. In case any secular textbooks had been found, it was agreed that I would be the scapegoat and claim the books were mine. Luckily, no such surprise ever occurred and my brothers managed to carry out their original plans. Somewhere along the line they met the famous journalist and novelist Illés Kaczér, one of the leading figures of Magyar Szellemi Társaság, the Hungarian Spiritual Association in Bratislava, which encouraged literary activity among the Hungarian minority in Czechoslovakia. My brothers started to participate in the Association’s meetings where they absorbed the prevailing atmosphere of liberalism and social democracy. Kaczér’s sons were Zionists and active members of Hasomer Hatzair a left-wing Zionist youth movement. My brothers met those ideas there, for the first time, ideas that influenced their outlook and way of life from then on. I was aware of changing times and new ideas, but was too young to “digest” them at that time.

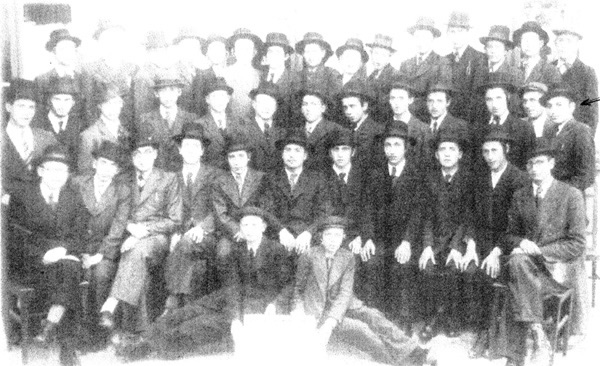

After the Pesach vacation of 1937, at the end of three semesters, I finished my studies at my Yeshiva Preparatory school (Yesodei Hatorah) and entered the Yeshiva of Sered (Sered nad Váhom) mentioned above. On arriving there, I was surprised to hear the Rabbi talking with the students in German, and not, as expected, in Yiddish and, moreover, addressing them in polite third-person mode, “Sie”, rather than the familiar Du (“Thou”). Rabbi Moshe Asher Eckstein was a very special person whose main concern was the physical welfare of his students. He established a dormitory to ensure that the boys lived in decent quarters, not in questionable sublets. He also founded a Mensa, a restaurant for students where they enjoyed free daily meals and personally supervised the menu. Such facilities were rare if nonexistent among the great majority of Yeshivot. His students were not compelled to eat “meals of charity”, every day in another household, as I was in Bratislava. He toured the Jewish communities of Slovakia and, through his extraordinary eloquence managed to raise sufficient funds, in cash and in products, to provide for the local Yeshiva and even for other institutes in Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia (the Eastern province of Czechoslovakia, now Carpatho Ukraine). Another specialty of this Yeshiva was its unique curriculum. Whereas the sole subject at most Yeshivot was Talmud, in this institute we had to study and memorize a chapter of the great Prophets or of Ketuvim, Hagiographa, every week. Owing to this “extra” work I still remember much of these chapters and enjoy this very much. I am convinced that memorizing parts of those supreme ideas and poetic language has greatly enriched my spiritual world and linguistic abilities. I would have gained this at no other Yeshiva. At the beginning of the second semester, the Rabbi invited me to serve as the home teacher of his teenaged son, although I was one of the youngest among his students. Sered nad Váhom is a town of Slovak population. The clerical-nationalist movement of the priest Hlinka enjoyed steady growth in the years 1937-38. Its youth organization, the “Hlinka Guards” became the “spearhead” of anti-Semitic activity all over the country. They were especially active and venomous in this town and became a serious nuisance in the streets. They bothered the walking Jewish girls there and sought ways to bump into the Yeshiva students. We made efforts to avoid them and to prevent possible scandals, but they insisted on provoking violent clashes. We felt that time had come to “pick up the challenge”. We organized a “gang” of some bold boys, who “were not afraid of their own shadow” (I was one of them) and went out cheerfully to the “promenade” where those hooligans used to stroll (without asking the Rabbi’s permission). We met our adversaries within a few minutes. They came leering and cursing to confront us. Our “leader” asked: “Do you want to be beaten, all of you?” and the clash started and lasted only a couple of minutes. The “brave” Guardians fled in every possible direction, screaming and aching all over. From then on, the streets of Sered were quiet and safe, no Jewish girl was bothered and the Yeshiva students could walk at pleasure on the their way. I met those nice hoodlums again in the fall of 1938, when they brought me my eviction order from Sered and practically the whole territory of the new Slovakia became under the rule of the clerical-fascist Hlinka party. I was considered Hungarian, because the whole Southern region of Slovakia, inhabited by Hungarians, including Nagymegyer, was annexed to Hungary. This was the end of the Czechoslovak republic after 20 years of existence. I left Sered and waited for the Hungarian authorities, military and civil administration, to arrive as far as nearby Galánta. After the “Parade of Liberation” I returned home, to Nagymegyer. |

||