Monika Hendry is a wonderful source for our genealogical quests, as she can speak Polish, and is researching her own ancestry. Although not Jewish, Monika is interested in the historical impact that Jews left in Poland. She feels Poland's Jewish heritage should be preserved for the benefit of Jewish communities and future generations of Poles, to help them shed prejudice and broaden their horizons.

The first thing that Monika found was a 32-page booklet titled "The Jewish Community in Old Jaslo" by Wladyslaw Mendys, published in 1992 by The Socio-Cultural Association of Jews in Poland. The book is based on the author's manuscript which was published in 1988 in Jaslo.

Monika writes: "I have translated the booklet and got permission

from Mr. Mendys' relatives to publish it for non-commercial

purposes.

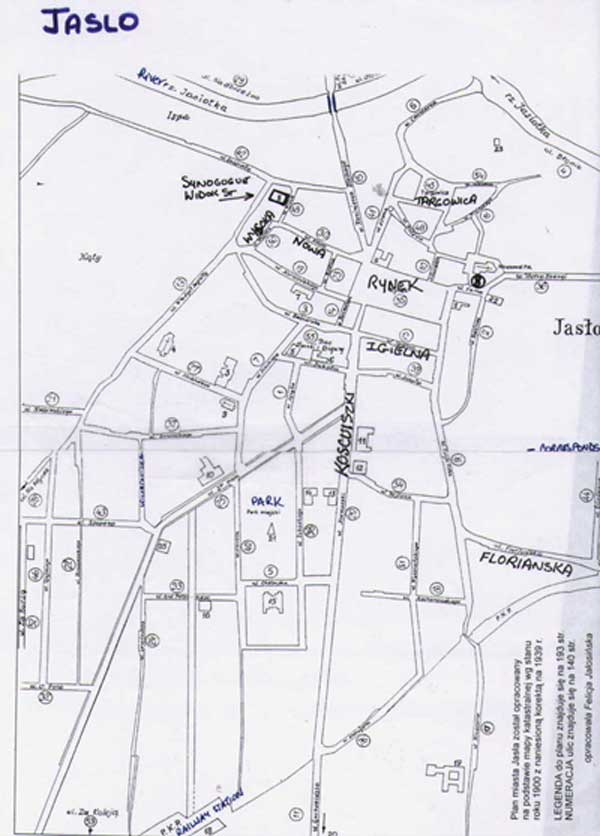

The photographs are from Monika, taken on her last trip to Jaslo, in July 2002. The map was also submitted by Monika.

Jaslo was the seat of the county government, district coal mining office and district court, with jurisdiction over the counties of Gorlice, Strzyzow, Krosno and Sanok. The town boasted one of the oldest high schools in the region - King Stanislaw Leszczynski's High School for Boys, and a few other schools. It also had the district post office, a tax office, a branch of the Bank of Poland, the State Oil Institute "Polomin", hospital and a railway hub. It also had two cinemas and two performance halls. As such, Jaslo was a significant political, economic and cultural centre.

Most buildings in Jaslo were single or double story

houses with gardens. Three story houses lined only the main streets

and could be counted on the fingers of one hand. There was only one

four story building in the whole town. The nicest place was the

park, situated in the town's centre. Streets and houses were very

neat and charming, making Jaslo one of the prettiest little towns in

the area.

Most buildings in Jaslo were single or double story

houses with gardens. Three story houses lined only the main streets

and could be counted on the fingers of one hand. There was only one

four story building in the whole town. The nicest place was the

park, situated in the town's centre. Streets and houses were very

neat and charming, making Jaslo one of the prettiest little towns in

the area.

Jaslo was not big. In the 1930s it covered an area of 6 square

kilometres and had 57 streets, excluding the suburbs and small

lanes. It had 1,090 houses, including 209 Jewish-owned which

represented roughly 19% of the total. Jewish houses were not

evenly distributed. There were streets without even one of them,

such as Na Blonie, Cmentarna, Golebia, Grunwaldzka, Kraszewskiego,

Klasztorna, W. Pola, Rejtana, Zielona. [The photograph on the

right shows a Jewish-owned house on Kazimierza Wielkiego

Street-Monika]. On some streets, such as Igielna, Krotka, Nowa,

Targowica and Widok, Jewish houses represented the majority. The

highest concentration of them was along Jaslo's main thoroughfare

Kazimierza Wielkiego. From the bridge on Jasiolka to the main

square (a distance of about 500m - Monika) there were 12 houses,

including 10 Jewish-owned. The owners were: Markus

Anisfeld, Benjamin Kramer, Dawid Elias, Maurycy Karpf, Pinkas

Lehr, Osias Brenner, Jakub Susskind, Salomea Kornfeld, Dawid

Goldstein and Izrael Plockier.  Other

predominantly Jewish streets were: Nowa, Stroma, Szajnochy, Widok

and Wysoka. These streets marked the section of the town with the

synagogue, cheder, prayer house, ritual bath and rabbi's house.

Other streets with Jewish residents such as Florianska, Igielna,

Wladyslawa Jagielly (part), Kazimierza Wielkiego, Kosicuszki,

Rynek and Targowica, were located in the centre at important

trading and economic points. This leads us to the conclusion that

Jaslo's Jewish residents chose their dwellings based not only on

religious and ethnic considerations but also on economic

conditions.

Other

predominantly Jewish streets were: Nowa, Stroma, Szajnochy, Widok

and Wysoka. These streets marked the section of the town with the

synagogue, cheder, prayer house, ritual bath and rabbi's house.

Other streets with Jewish residents such as Florianska, Igielna,

Wladyslawa Jagielly (part), Kazimierza Wielkiego, Kosicuszki,

Rynek and Targowica, were located in the centre at important

trading and economic points. This leads us to the conclusion that

Jaslo's Jewish residents chose their dwellings based not only on

religious and ethnic considerations but also on economic

conditions.

The trade in cattle and other animals took place on a big square called "Targowica". The buildings around it housed seven shops including five owned by Jews. In the streets leading to the main square Jewish shops dominated. On Szajnochy street, where the prayer house stood, there were nine shops, all Jewish-owned. On Kosciuszki, the main thoroughfare, there were 31 shops, 21 of them Jewish-owned. On Kazimierza Wielkiego there were 22 shops, including 19 Jewish-owned, on Igielna all six shops belonged to Jews. Jews also dominated in terms of the variety of goods. The most common were mix-goods shops, which sold almost everything, including food, and industrial products. These shops targeted farmers and stocked all the necessities: flour, sugar, sweets, fabrics, leather products, chemicals and even tools.

The photo at the right is of the Rynek or main square; if you

look closely you will see the Zimet store on the right!

Jewish restaurants could be found on all main roads leading to the town. They were like customs posts collecting "toll" from everyone who passed by. Many Jewish shops sold assorted goods, fabrics, clothes, shoes, iron products, paper and toys. Shops with "Meat Products" made up another category. Some sectors of retail were completely dominated by Jews. These include furniture, leather and clothes. Some Jewish restaurants played a significant role in the social life in Jaslo. For example, adjacent to a spice shop situated in the main square and owned by Max Koegel, was a very smart breakfast room, frequented only by sophisticated customers. It served gourmet snacks and expensive liquors. Similar, but slightly different in character was the restaurant "U Lajci" also in the square. It was run by Laja (Leah) Margulies. It became customary for local officials and VIPs to turn up there for their Sabbath delicacies - fish Jewish style, Jewish caviar and chala, sprinkled with a few glasses of Sabbath vodka.

Another type of restaurant, on the town's outskirts, was run by Rosa Spett. This place was very popular with court secretaries, although the menu was limited mainly to herring.

A typical tavern, about 2 kilometres from Jaslo's centre, was run by Chaim Fallek. It was next to a big garden full of tables and benches and it was the usual destination of families taking their Sunday strolls in the summer. An ordinary "watering hole" on Kazimierza Wielkiego street was run by Schwimmer. For a long time a retired official called J. St run his legal consultancy business out of it. At any time of the day, he could be seen sitting at the table, his head in his hands, and pondering a case just submitted by a humble peasant, seated on a chair next to him. If his silence lasted for too long, the impatient customer would shyly suggest "your lordship, how about a small beer?" Hearing that, J. St. would leap to his feet and, his face twisted with indignation, shout "you oaf! I had a great idea and you interrupted me with a small beer! Order a big beer then!"

Jewish shops varied in terms of location and facilities. Many were located in small, dark, stuffy rooms and were not very clean. However, there were also high-class shops including that of Adolf Margulies (iron and technical products in the square), Edmund Dab (iron products and tools), J. Menasse and Wistreich (textiles and fabrics), Benjamin Kramer (flour products on Kazimierz Wielki Street), Goldner (accessories on Kosciuszki street), N. Kunstler and Summer (grains), Finkla Bodne (foodstuffs on Kosciuszki street), Anna Blaser (leather products on Kosciuszki), David Wildforth (spices and colonial goods on Kosciuszki),Anna Dranger (women's accessories) , Meilech Krischer (shoes and accessories on the corner of Kosciuszki and May 3 streets), Amalia Kalb (textiles on May 3 street), Mendel Meller (leather on May 3 street), B. Just (jewllery and watches on Kosciuszki street), Esther Blum (ladies' fashion on Kosciuszki street) and L. Baumring (spices on Kosciuszki street).

Out of Jaslo's three brick factories, two were Jewish-owned. One

belonged to industrialist Boguslaw Steinhaus,

the other to Bruno Schmindling. Forscher owned a

shoe polish factory "Luna", Geminder a broom and

brush factory and Grunspann a tannery. Next to

the train station, there was a large mining equipment storage and

workshop, which belonged to Ringler. Jewish

craftsmen were in minority but their workshops were very

sophisticated and specialised. Shoemaker Moses  Schips was excellent at cutting uppers.

Tinsmith Bruder made roofs but also could make

and repair any tin container. In addition to ordinary hats, hatter

Pinkas Leer made elegant student caps. There were three

freight companies run by Feinchel, Finder and Kriger .

Some crafts did not seem attractive to Jews - there were no Jewish

smiths, bricklayers, stonecutters and carpenters. Nor there were

any Jewish railwaymen. It is difficult to establish why, perhaps

Jews considered working in these professions as too hard or

entailing some health risks or dangers.

Schips was excellent at cutting uppers.

Tinsmith Bruder made roofs but also could make

and repair any tin container. In addition to ordinary hats, hatter

Pinkas Leer made elegant student caps. There were three

freight companies run by Feinchel, Finder and Kriger .

Some crafts did not seem attractive to Jews - there were no Jewish

smiths, bricklayers, stonecutters and carpenters. Nor there were

any Jewish railwaymen. It is difficult to establish why, perhaps

Jews considered working in these professions as too hard or

entailing some health risks or dangers.

Jaslo had six barber shops, including four Jewish-owned. On market days, farmers, their main customers, arrived en masse in town and the shops were busy finding ways to lure them in. Apparently, one Jewish barber developed a trick that prevented anybody who entered his shop from leaving without a shave. He'd soap all the waiting customers and shave off a small patch on their faces. Only then would he proceed to give each of them a full shave. This way he ensured that customers waited patiently for their turn. Jaslo also had two photo shops. One was called Flora, the other was owned by Fenichel sisters.

Jaslo, as the seat of the district court with jurisdiction over the counties of Jaslo, Krosno, Gorlice, Sanok and Strzyzow, had more than 30 lawyer offices, including 19 Jewish-owned. Competition was intense and the ethical and professional standards varied. Some were very serious with good reputations. Some eked an existence out of inciting feuds among farmers who were always eager to sue over even an inch of land. The most reputable legal practices, especially those serving the oil industry, were very profitable, which was well reflected in the lifestyles of their lawyers. They also played a significant role in the development of Jaslo's Jewish intelligentsia. The elite of Jewish lawyers included Bernard Appel, Stanislaw Gottlieb, Jakub Herzig, Adolf Kaczkowski, Maurycy Karpf, Abraham Kornhauzer, Abraham Menasse, Naftali Menasse, Ludwig Oberlander, Izrael Plockier, Leon Reichman, Henryk Rosenbuch, Ignacy Rosenfeld, Alfred Rosner, Herman Stein and Fichel Welfeld.

The only surveyor in Jaslo was an engineer of Jewish origins, Bertold Oczeret. The only bank and foreign exchange counter was run by Bernard Kornfeld. Many Jews residents unofficially worked as middlemen. Independently of their roles in Jaslo's economic life, many Jews held posts related to their religion and its rites. At the top of the religious hierarchy were rabbis. In Jaslo this position was held by (rabbis) Mozes Rubin, Zuckermann and Halberstamm. No less important were religious teachers, represented by Akiwa Hoffman and Abraham Diller, both highly educated and very cultured. Then followed those in charge of the synagogue, ritual slaughter of cows and chicken, and the Hebrew teacher, called melamed.

Jewish men stood out from the locals because of the way they dressed. The most common outfit for men was a black, long, buttoned up to the neck coat. They wore black velvet or velour hats and under them, in line with Talmudic rules, black skullcaps, called jarmulka or birytka, which they never took off, indoors or outdoors. Jewish women dressed the same way as local women. Their characteristic feature was, in line with Talmudic rules, a shaven head. Nearly all married women wore wigs, often adorned with precious pearls. Jewish upper classes, such as intelligentsia and financiers, dressed very elegantly and followed European fashion. They treated Jewish masses with slight disdain.

However in matters concerning interests of the whole community, Jews were always very united. They adhered to the rule of not involving goyim in their affairs. The only discords, which sometimes became quite serious between the orthodox and the progressive, were limited to religious issues. These, however, always came second to the matters of importance for the whole community. Here is an example to illustrate the level of disagreement among the orthodox and progressive Jews:

Mr.Ch.D, an orthodox whose son was educated by a rabbi, and Mr.

M.E, a progressive Jew, jointly owned a single story house on

Jaslo's main street. They had equal shares but the wall that

divided the ground floor in half, on the second floor run a few

inches askew so the parts were not equal. This gave rise to a

dispute. All attempts to reconcile them failed because of Mr. Ch's

animosity towards the progressive Mr. E. The case was put to the

court and after a few appeals ended up in the Supreme Court in

Warsaw. Mr. Ch. employed a Polish lawyer from Jaslo and sent him

to Warsaw saying the he feared that Mr.E "this Ganef, this

apikoyres", cunning as a snake, might bribe a Warsaw lawyer or

devise some other trick.

In this case, religious fanaticism took precedence over ethnic

loyalty.

Here's an example: Two Jewish partners run a prosperous business together and make a small fortune. They divide the money and each goes his own way. Itzhak bought a factory and Moritz a country estate. After a while, Itzhak started worrying that Moritz made a better move. His wife, Sarah, suggested that the best way to find out would be to visit Moritz and ask him. Itzhak followed her advice. He reached a magnificent mansion with a servant in a livery. Itzhak asked for Moritz and was told that the master of the house is now called Maurycy (Maurice). The old friends greeted each other cheerfully and Itzhak asked Moritz how he was doing. Moritz replied that now his life was a bed of roses. "I do nothing, others work for me. After I get up in the morning, I lay on the veranda for a while. After breakfast, I do more of the same. Then I check what my people are doing and rest on the veranda again. Then, there's lunch and after that I again rest on the veranda until the evening. It is a beautiful life. How about you?" Itzhak told Moritz about himself and left. At home his wife is very curious - "so how is Moritz doing?" "Well, he is now called Maurycy". "OK. And how is Rifka?" "She is now called Veranda".

German speakers could easily understand Yiddish. In fact, almost every Jew could speak German. Many Poles could speak fluent Yiddish as well as many Jews could speak Polish, although many had problems with pronunciation. Jewish intellectuals frequently spoke very good Polish.

When the Sabbath hour was approaching, Jews would close their shops and workshops and hurry home. Streets emptied and traffic slowed down. Jewish districts looked deserted. Later in the evening, groups of Jewish men, wearing their best clothes, emerged rushing to the synagogue. Their clothes differed from the ordinary day attire. They wore long, black and shiny coats, long, white socks and black shoes. Their black hats were adorned with red fur, usually fox tails, giving rise to the name "fox hats". An empty street with a lone group of figures in their best clothes, with faces covered with black and red beards looked exotic indeed. They carried their black velvet bags with prayer accessories to the synagogue. They included: "talis" - a wide black and white striped shawl with long tassels and tefilim - a small leather box containing a bit of Torah. When praying, they tied their tefilim to their foreheads, covered their shoulders with the "talis" and tied the leather straps around their forearms. They moved their bodies as if in some sort of religious trance. With so many people, the synagogue was filled with loud wails and noise. This created a typical sound background for the whole district. After the prayers, everybody returned home to have dinner.

Apart from the weekly Sabbath, Jews also celebrated several annual holidays. The most important and pompous was Yom Kippur. The day was a strict fast. One of the customs was to go to a river to shake out crumbs and dirt out of one's pockets, which symbolised shedding of the sins. On the day, all Jewish residents would gather in the synagogue with their wives and children and spend long hours singing. A famous cantor was employed for the occasion and his singing would deeply move the audience. Poles were frequently welcomed to take part in these celebrations and were eager to jump on the chance to listen to the cantor's beautiful singing.

No less important was Pesach, commemorating the liberation from Egypt. During this holiday Jews ate "maca"- thin crisp bread made of wheat flour without any yeast or salt. They shared their maca with friends and relatives. In the autumn, Jews celebrated "kuczki"- Holiday of Tents, to commemorate their journey in the desert. Customs related to this holiday also used to leave a deep mark on Jaslo's life and appearance. Talmudic rules forbade Jews leaving their dwellings during the holiday. To show that rule, they would mark the border of their properties with a wire on pickets. In order to keep this Talmudic rule and at the same time maintain some degree of free movement, they would put the pickets as far as possible, frequently fencing off whole sections of the street. The celebrations lasted for a few days keeping whole districts behind the wire. During this time Jews also set up tents and sheds ("kuczki") in their yards. This made the Jewish district look like a big camp. Important among private and social occasions were weddings with their climax of shattering a glass and shouting "mazel-tov".

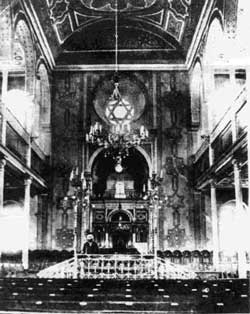

The synagogue was the Jewish social and

religious centre.

The synagogue was the Jewish social and

religious centre. Monika Hendry located this photograph on the left of the

interior of the old synagogue......isn't it marvelous!!

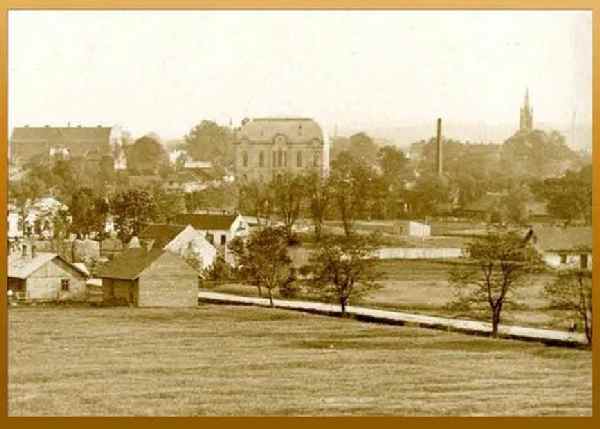

And then the 1916 postcard of the view toward the synagogue!

Then in 2019  Monika wrote:

"Came across this photo on a Jaslo page on FB - have not seen

many pictures of synagogue during the war. This must have been

take right after it was set on fire and the roof burnt down in

1939." The synagogue is the building to the right. As always,

thankyou Monika!!

Monika wrote:

"Came across this photo on a Jaslo page on FB - have not seen

many pictures of synagogue during the war. This must have been

take right after it was set on fire and the roof burnt down in

1939." The synagogue is the building to the right. As always,

thankyou Monika!!

Jaslo also had an old synagogue, which served as a daily prayer place, housed a cheder and the rabbi's office. Right next to it was a ritual bath. Jaslo's Jewish community had its own cemetery called "kirkut" on the town's outskirts.. Funerals were held in the evenings, and the procession would move very swiftly, as if in a hurry. Funerals were led by a rabbi and cantor. Wealthy families sometimes invited a famous cantor who would sing a very moving mourning song "Kl Mole", a masterpiece of music and poetry. Jews have a very well-developed cult of the dead. Each grave had a stone, matzeva, with carved symbols or the star of David and Hebrew writing. The stone was put at the feet not the head of the deceased.

Jaslo's Jewish community had very high and strictly adhered to moral standards. There were no drunks, troublemakers or thieves. Beggars or wanderers were a rarity. Family ties were very strong. The old were respected and had high authority. No discords ever filtered outside. It was unthinkable that a man would abuse his wife or children. On the doorframe at the entrance of a Jewish house they attached a small box "mezuza" containing a piece of paper God's commandments. Every Jew passing through the door would touch it and kiss his fingers, to show his reverence to the Torah.

In their daily life, Jews distinguished themselves as very hardworking, frugal and content-with-little people. A Jew would sit in his shop or a workshop from dawn to dusk. Even after his business hours he would never send a customer away empty handed. He'd never miss a chance to make a little money. Thanks to this attitude many Jews became quite wealthy and managed to transform themselves from looked-down-upon traders to respected members of the society. A daughter's dowry or son's education was behind their drive to amass wealth. This drive combined with their high intelligence frequently produced stunning results. One of the greatest examples is Hugo Steinhaus, a world famous mathematician, born and educated in Jaslo. Another two students of Jaslo's college - Zygmunt Goldschlag (son of the director of the refinery) and Wladyslaw Steinhaus (son of an industrialist) were members of Pilsudski's legions.

Monika said: "The list of names follows - many surnames are identical to those in Krosno, in some cases even first names, which suggests that these people may have lived in Krosno and maintained businesses in Jaslo. I believe it covers the time between the wars but the booklet does not give any dates."

In January of 2006, Monika added: these two pictures of

Jaslo Jews were printed in Mr. Mendys' booklet (the one I

translated).  Since I have permission to reproduce

Since I have permission to reproduce  the

booklet, i reproduced the photographs in it."

the

booklet, i reproduced the photographs in it."

Editor's note: I have removed the list of surnames from the book and added them to the Jaslo table below.

For more information, email Monika Hendry

Return to Krosno's Table of

Contents br> Return to

Jaslo's Table of Contents

Monika Hendry has done it again….in September of 2013 she wrote:

“By a complete chance, I found the website of a digital library in Rzeszow which has a lot of assorted documents from the region so I am just scratching the surface. http://www.pbc.rzeszow.pl/dlibra/plain-content?id=722. So far, I have discovered annual report books for Jaslo for many of the years from 1878 through 1930 (1878-9, 1883-4,1888-94, 1897-9, 1901-2, 1904, 1907-13, 1915-19, 1930/31). And I still have to check many more tabs on that website.

The books are a treasure trove of information. Later ones

detail individual donations to the school - lots of Jewish

businessmen contributed. They even detail the topics of

homework essays given to students throughout the year. I

noticed that the teaching was Latin- heavy. In the first class

of year 1907/08, students had 8 hours of Latin a week, 6 hours

of German and 3 hours of Polish.  In third class, Latin was cut down to 6 hours

and German to 4, but 4 hours of Greek were added. In both

cases, they had only 3 hours of math, 2 hours of natural

history and 2 hours of physical education, but it says that

"during the long break, students were encouraged to play ball

games, tug of war and practice stilt walking". Akiva Hoffman

was the religion teacher - he taught only 2 hours a week.

In third class, Latin was cut down to 6 hours

and German to 4, but 4 hours of Greek were added. In both

cases, they had only 3 hours of math, 2 hours of natural

history and 2 hours of physical education, but it says that

"during the long break, students were encouraged to play ball

games, tug of war and practice stilt walking". Akiva Hoffman

was the religion teacher - he taught only 2 hours a week.

I’m so happy to have new information for the Jaslo page.”

” The digital files are owned by the City Library of Rzeszow. I am sure there's much more info in there. I am just scratching the surface.... At the bottom of the Library page under this link you will find a "linki zewnetrzne" (external links) with loads of dates - these are links to the so called Schematismus des Konigsreiches Galizien und Lodomerien (Schematisms of Galicia and Lodomeria) - annual reports about administrative organs in Galicia, listing surnames of teachers, clerks, civil servants, MPs, delegates, members of associations, charities, notaries, lawyers, employees of district courts etc so a surname mine for sure: http://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Szematyzm_Kr%C3%B3lestwa_Galicji_i_Lodomerii_z_Wielkim_Ksi%C4%99stwem_Krakowskim”

| Year | Total no.students | Jewish students |

| 1878 | 331 | 4 |

| 1879 | 357 | 8 |

| 1880 | 347 | 5 |

| 1882 | 323 | 9 |

| 1883 | 376 | 15 |

| 1884 | 389 | 11 |

| 1886 | 396 | 18 |

| 1887 | 391 | 18 |

| 1888 | 423 | 21 |

| 1890 | 444 | 22 |

| 1891 | 432 | 19 |

| 1892 | 481 | 44 |

| 1893 | 479 | 28 |

| 1894 | 453 | 26 |

| 1895 | 488 | 25 |

| 1897 | 494 | 27 |

| 1898 | 489 | 22 |

| 1899 | 532 | 21 |

| 1901 | 638 | 31 |

| 1902 | 637 | 28 |

| 1904 | 692 | 35 |

| 1905 | 710 | 44 |

| 1908 | 575 | 42 |

| 1909 | 578 | 38 |

| 1911 | 556 | 30 |

| 1912 | 576 | 33 |

| 1913 | 570 | 33 |

| 1916 | 479 | 25 |

| 1917 | 471 | 34 |

| 1918 | 460 | 42 |

| 1919 | 507 | 49 |

| 1930 | 559 | 46 |

I asked

Monika about some of the surnames that didn’t appear

“Jewish” and she wrote:

” We are safe here, a Jewish lawyer, Adolf Kaczkowski, is

also mentioned in the booklet I translated for the

Shtetlinks. The booklet was written by a Polish lawyer, Mr.

Mendys, who went to school with a bunch of Kaczkowskis so I

am sure he should know. There's also another Jewish family

with a very Polish surname Dab (means: oak) and some of them

took non-Jewish names like Edmund.

I also know that many Jewish families liked to call their

boys Leon, Isidore, Leopold, Zygmunt, Ignacy, Reginald etc -

these are fairly common Polish names but for some reason

more assimilated Jews liked them too. Same with Stanislaw, a

standard substitute for Salomon.

So yes, in many cases I am going by a hunch but I am still

conservative because I don't think I ever identify as many

Jewish students as they say attended in any given year. I am

always short of at least 5-6 names. So there must have been

Jewish students with completely Polish names that are

indistinguishable. I was also surprised to discover that the

teacher of religion in the boys' school was called

Schlesinger Maciej - this is the first Jewish man named

Maciej I have ever seen but he is clearly identified in the

book as being Jewish. “

(Found by Monika in the Rzeszow Archives)

In 1921-1927, Jaslo was a quiet town of pensioners and civil servants, not very industrialized and with sluggish trade. Away from the main railway of Lesser Poland (Malopolska), linking Rzeszow with Cracow and Lviv, it was situated on a local branch railway line to Rzeszow. I remember, in grade 5, Wojtek Urbas (now a priest), my desk-mate at school and I would go every afternoon to the Jaslo train station. This way, subconsciously, we tried to satisfy our longing for traveling, for exploring the wide world that lay beyond those rail tracks. We rarely went to the cinema. We read Karl May in 3rd and 4th grade – that was our dose of fantasy.

Jaslo was a quiet town, well known in Lesser Poland for order and cleanliness. Our school building was the most imposing and beautiful in town. We were proud of our school, of its red brick façade that peeked from behind the trees which formed what we called “the grove of Akademos”, where older students used to take strolls during recess. The yard behind the building was for the youngsters, who spent their breaks screaming, poking and chasing one another. The atmosphere of our school was unforgettable, nice and relaxed. The teachers stroke a happy medium between discipline and freedom. There were never any conflicts related to nationality or anything else. Professors and other staff worked together in the spirit of tolerance, understanding and mutual respect.

In response to this wonderful find, I have created an alphabetical table of names from this resource and others from JASLO. Sources are detailed in other parts of this Kehilalinks site, and include:

Check back often as the table will be updated as

Monika translates each list!!

Phyllis Kramer, web page creator and editor, September

2013

| Surname, Given | Source: School or Stone or Directory | Additional Comments, address |

| "Grand" | 1929 City Directory | Hotel, Czackiego Street |

| "Wisloka" Co Ltd | 1929 City Directory | Printing house, Targowica (market place). |

| “Harmonja” | 1929 City Directory | Cinema, Kolejowa Street |

| “Sokol” | 1929 City Directory | Cinema, Sokola Street |

| Aberbach, Israel | 1913 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a | |

| Adler | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Adler, Morye? - textiles (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 17 Rynek, Pirzeja |

| Adler, Samuel | 1926 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Adler,Ch | 1929 City Directory | Textiles/Fabrics, Rynek (main square), |

| Ahment, Abraham | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Ahment, Abraham | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 41 Ulica Jagielly |

| Ahment, Abraham - tinsmith | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 16 Ulica Krasinskiego |

| Aksamit | 1916 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 6K | |

| Aksamit, Boleslaw | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 3a | |

| Aksamit, Boleslaw | 1918 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4b | |

| Aksamit, Franciszek | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 3b | |

| Aksamit, Mieczyslaw | 1918 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a | |

| Altman, Herman | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Altman, O | 1929 City Directory | Eggs, Targowica (market square), |

| Altman, Szyja | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Altman, Szyja - assorted goods | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 48 Ulica Florianska |

| Altman,P | 1929 City Directory | Assorted goods, Kazimierza Wielkiego Street |

| Altmann (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 2 Ulica Szajnochy |

| Altmann, Herman | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 31 Ulica Szajnochy |

| Altmann, Herman | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 17 Ulica Targowica |

| Altmann, N | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 42 Ulica Florianska |

| Altmann, N | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 47 Ulica Kazimierza Wielkiego |

| Altmann, Szyja | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 12 Ulica Rejtana |

| Altmann,J | 1929 City Directory | Textiles/Fabrics, Florianska Street |

| Amais, Leizor | 1883-84 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b/2b | |

| Ament,M | 1929 City Directory | Tin makers |

| Anisfeld, Dorota | 1925 Graduated B.Y.H.S., class of 1925 | Born 22 Feb 1907 in Trzcinica |

| Anisfeld, Jan | 1926 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Anisfeld, Marcus | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Anisfeld, Markus - propinacja | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 1 Ulica Kazimierza Wielkiego |

| Anisfeld,M | 1929 City Directory | Spirits retail, Nowa Street |

| Anisfeld. Jan – engineer | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Apfel Gitla | 1913 Business Directory | Paper Products |

| Apfel Gitla | 1913 Business Directory | Sundry Goods (Rynek) |

| Apfel, Bernard (lawyer) | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Apfel, Gita | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Apfel,G | 1929 City Directory | Assorted goods, Rynek |

| Appel | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Appel, Amalia | 1920/1921, B.Y.H.S. Class of 1920/21 | |

| Appel, Bernard? - ritual butcher | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 13 Ulica Szajnochy |

| Appel, Gitla | 1925-7, Class 6-8, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Appel, Gitla - stationary shop (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 5 Rynek, Pirzeja |

| Appel, Gitla Syma | 1927 Graduated B.Y.H.S., class of 1927 | Born 2 Aug 1908 Przemysl |

| Appel, Salomea | 1928-1931, Class 4-7, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Appel. Bernard – lawyer | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Aszkenazy,H | 1929 City Directory | Accessories, Rynek |

| Ausenberg,M | 1929 City Directory | Animal skins, Rynek |

| Aussenberg | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Aussenberg, Izaak | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 10 Ulica Targowica |

| Bajer,S | 1929 City Directory | Tavern, Stroma Street |

| Bak,A | 1929 City Directory | Accessories, Czackiego Street |

| Bak,A | 1929 City Directory | Real Estate, Rynek |

| Bak,J | 1929 City Directory | Insurance, “Przezornosc” Rynek, |

| Bana,J | 1929 City Directory | Ladies’ Tailor, Igielna Street |

| Baranowski | 1929 City Directory | Lawyer |

| Barnas,F | 1929 City Directory | Goldsmiths, Koralewskiego Street |

| Baumring | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 10K | |

| Baumring, Anna | 1929 Graduated B.Y.H.S. 1929 | Born 7 Feb 1910 in Jaslo |

| Baumring, Anna | 1929, Class 8, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Baumring, Isaac | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4a | |

| Baumring, Isaac | 1921 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Baumring, Leon | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 10 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Baumring, Leon (dentist) | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Baumring,H | 1929 City Directory | Assorted goods, Kosciuszki Street |

| Baumring. Isaac – dentist | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Bayer, Jacob | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5a | |

| Bayer, Jacob | 1934 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Beck | 1929 City Directory | Lime, Igielna Street Stroma Street |

| Beck | 1929 City Directory | Coal |

| Beck Moses | 1913 Business Directory | firewood |

| Beck Moses coal | 1913 Business Directory | Coal |

| Beck, Abraham | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5b | |

| Beck, Isaac | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5a | |

| Beck, Israel | 1933 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Beck, Joel | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8b | |

| Beck, Joel Mendel | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 & graduated | b. 28 Dec 1909 in Jaslo |

| Beck, Markus | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Beck, Markus | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 22 Ulica Basztowa |

| Beck, Markus - coal | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 17 Ulica Koralewskiego |

| Beck, Markus - coal storage | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 2 Ulica Florianska |

| Beck, Mendel | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8b | |

| Beck, N, Morgenstern, N, Ryczaj, N | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 21 Ulica Kazimierza Wielkiego |

| Begleiter, Zygmunt - gas station and glass works -built in 1923 | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 8 Ulica Sniadeckich |

| Beldengrun, Natan - butcher | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 21 Ulica Targowica |

| Beldengrun, O. | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Benenstock, Ignacy | 1924 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Berger ,Stanislaw | 1895 C.K. Gimnazyum – graduated | |

| Berger, Chaskiel - bags | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 6 Ulica Widok |

| Berger, N | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 18 Ulica Sokola |

| Berger, P. | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Berger, Zacharias | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2a | |

| Berger,D | 1929 City Directory | Delicatessen |

| Berger,D. | 1929 City Directory | Forwarding Office, Stroma Street |

| Bergerowie, N.N. | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 41 Ulica Florianska |

| Bergman,T | 1929 City Directory | Ladies’ Tailor, Targowica |

| Berner | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Berner Isaac | 1913 Business Directory | Paper Products |

| Berner, Balbina | 1925 Graduated B.Y.H.S. | Born 17 Dec 1907 in Jaslo |

| Berner, Isidore | 1925 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Berner, Jude | 1893 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 3b | |

| Berner, N - bookstore (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 23 Rynek, Pirzeja |

| Berner,H | 1929 City Directory | Bookstore, Rynek |

| Berner. Emmanuel – merchant from Jaslo | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Bernstein, M | 1908 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 40K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Bernstein, Maria | 1909 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 20K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Bezener, Anna | 1920/1921, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Bialywlos,A | 1929 City Directory | Accessories, 3 Maja Street |

| Bienenstock, Ignacy | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b | |

| Biller, Abraham | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Binenstock,J | 1929 City Directory | Furniture, Kazimierza Wielkiego Street |

| Birn, Abraham | 1891-92-93-94 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b/2b/3a/4a | |

| Blaser Elias | 1913 Business Directory | leather trade |

| Blaser, Anna | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Blaser, Anna | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 17 Ulica Slowackiego |

| Blaser, Anna - leather shop (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 33 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Blaser,E | 1929 City Directory | Shoes, Kosciuszki Street |

| Blatt, Helena | 1925, Class 1, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Blazer,E | 1929 City Directory | Animal skins, Kosciuszki Street |

| Blech, Jacob | 1905 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b | |

| Bleimann, Juma | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Bleimann, Juma - scraps purchasing center | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 17 Ulica Basztowa |

| Blum, A | 1929 City Directory | Pharmacy, "Pod Gwiazda" |

| Blum, Anna - ladies fashion (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 34 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Blum, I | 1929 City Directory | Accessories, Rynek |

| Blum, Regina | 1930-1, Class 4-5, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Blum,Ch | 1929 City Directory | Accessories, Kosciuszki Street |

| Blum,Estera | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Blumenkrantz, Zalel | 1899 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2a | |

| Blumenkrantz, Zalel | 1901 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4a | |

| Blumenkranz, Zalel | 1898 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a | |

| Blumenthal | 1916 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 12K | |

| Blumenthal, Arthur | 1918 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 6a | |

| Blumenthal, Artur | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5a | |

| Blumenthal, Artur | 1920 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Bluth | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Bober, Hersch | 1879 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b | |

| Bock, Eugeniusz | 1897 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b | |

| Bock, Gabriel | 1901 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5b | |

| Bock, Gabriel | 1904 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Bodne(r?), Finkla | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Bodner, Nathan | 1913 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b | |

| Bodner,Finkla - flour goods (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 33 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Bogen, David | 1908 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 4K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Boldengrun,S | 1929 City Directory | Butcher, Kosciuszki Street |

| Bonder,F | 1929 City Directory | Assorted goods, Kosciuszki Street |

| Brandstatter, Ignacy | 1890 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b | |

| Brandstatter, Isaac | 1896-8 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 6/7 | adult student, externist (studies on his own but takes all the exams) |

| Brandstetter, Isaac | 1893-94-95-97-98 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4/5/6/8/graduated | Mature, adult student |

| Brandstetter, Leopold | 1899-1902 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b/3a | |

| Braun, Salomea | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Braunseis, Jadwiga | 1925, Class 4, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Braunseis, Jadwiga | 1929, Class 8, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Breitmeier, Adam | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5a | |

| Brenner, Helena | 1925, Class 8, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Brenner, Osias | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Brenner, Osias | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 6 Ulica Kazimierza Wielkiego |

| Brenner,L | 1929 City Directory | Timber, Kazimierza Wielkiego Street |

| Broch, Moses | 1901 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 3a | |

| Broch, Napthali | 1897 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b | |

| Bruck, N - butcher (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 16 Rynek, Pirzeja |

| Bruck, N - cattle trader | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 23 Ulica Szajnochy |

| Bruck, O. | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Bruck,M | 1929 City Directory | Butcher, Rynek |

| Bruder, N - hall painter | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 7 Ulica Koralewskiego |

| Bruder, O. tinsmith | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Bruder, Osias - hall Painter | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 8 Ulica Bednarska |

| Bruder, Salamon - tinsmith | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 17 Ulica Nowa |

| Bruder, Salomon | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Bruder, Samuel | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Bruder,J | 1929 City Directory | Tin makers |

| Bruder,S | 1929 City Directory | Painter |

| Buba,J | 1929 City Directory | Book Binding |

| Buchelt,H | 1929 City Directory | Real Estate, Franciszkanska Street |

| Bukiewicz, J | 1929 City Directory | Midwife |

| Bukiewicz. | 1929 City Directory | Lawyer |

| Bydon,J | 1929 City Directory | Ginger bread, Koralewskiego Street |

| Chaim, Dawid | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Chaim, Dawid - corner | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 4 Ulica Chelmska |

| Chaim, Dawid - tavern | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 43 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Chaskiel, Meth | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4b | |

| Chil, David | 1893 C.K. Gimnazyum – graduated | |

| Cislo, Jakub - bar | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 73 Ulica 3-go Maja |

| Cymerman, Stanislaw | 1902 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b | |

| Cymerman, Stanislaw | 1905 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4b | |

| Cymerman, Stanislaw | 1908 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 7b | |

| Cymerman, Stanislaw | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 7a | |

| Cymerman, Stanislaw | 1932 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Cymerman. Stanislaw – colonel | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| CzernySzwarcenberg | 1929 City Directory | Lawyer |

| Czopp, Nathan | 1911 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 4K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Czopp, Olga | 1911 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a | (private female student) |

| Czopp, Olga | 1912 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2a | (private female student) |

| Czopp, Olga | 1913 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 5K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Czopp, Olga | 1913 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 3a | |

| Dab (Domb) Napthali | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 & graduated | born 8 Oct 1901 in Rymanow |

| Dab (Domb), Napthali – doctor from Biecz | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Dab Edward | 1913 Business Directory | Iron and Machinery |

| Dab, Edmund | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Dab, Edmund - scrap metal, iron recycling | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 1 Ulica Kochanowskiego |

| Dab, Edmund - storage yard | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 6 Ulica Kochanowskiego |

| Dab, Leopold | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2 | |

| Dab, Leopold | 1922 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Dab, Naftali | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 23 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Dab, Naftali - iron recycling | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 14 Ulica Wyspianskiego |

| Dab, Naftali - metal goods (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 27 Rynek, Pirzeja |

| Dab, Napthali | 1912 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a | |

| Dab, Napthali | 1913 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2a | |

| Dab, Napthali | 1918 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 7a | |

| Dab,Edmund | 1929 City Directory | Agricultural equipment, Kosciuszki Street |

| Dab,Edmund | 1929 City Directory | Iron, Kosciuszki Street |

| Dab,S | 1929 City Directory | Kitchen Utensils, Kazimierza Wielkiego Street |

| Dab. Leopold – merchant from Jaslo | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Damashek, Jacob | 1926 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Damaszek, Markus | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Dankmeier. Hugo | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Dankmeyer, Hugo | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8a | |

| Dankmeyer, Ludwik | 1926 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Dankmeyer. Ludwik | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Dasiewicz,R | 1929 City Directory | Sausages, meat products, Piotra Skargi Street |

| Deisenberg, Adam | 1912 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 7b | |

| Deisenberg, Adam | 1913 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8b | |

| Denner, David | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Denner, Dawid | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 16 Ulica Jagielly |

| Denner, Juma | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Denner, Juma & Beila | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 17 Ulica Jagielly |

| Denner,D | 1929 City Directory | Butcher, Bednarska Street |

| Diamond, Markus – clothes shop | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 12 Ulica Nowa |

| Dietl, Roman | 1911 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8b | |

| Dilgacz, Salomea | Graduated B.Y.H.S. 1926 | Born 3 Feb 1908 Podwoloczyska |

| Diller, Abraham (teacher) | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Diller, Bina | 1930-1, Class 6-7b, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Diller, Chaim | 1922/1923, B.Y.H.S. Teacher | |

| Diller, Chaim – Judiasm Teacher | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 2 Ulica Wyspianskiego |

| Diller, Deborah | 1925-7, Class 6,7, 8, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Diller, Deborah | 1927 Graduated B.Y.H.S., class of 1927 | Born 12 Nov 1908 Jaslo |

| Diller, Isaac | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Diller, Isaac | 1929 Jewish Teacher, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Diller, Israel | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b | |

| Diller, Israel | 1918 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b | |

| Diller, Israel | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 3b | |

| Diller, Sabina | 1928-9, Class 4-5b, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Dilmer, Isaac | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5b | |

| Dintenfloss, Israel | 1902 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5a | |

| Dligacz, Isaac | 1927 religious teacher, also 1928 | |

| Dranger, Anna | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Dranger, Anna - ladies accessories (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 9 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Dranger, Bina | 1928-9, Class 5-6, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Dranger,B, | 1929 City Directory | Accessories, Kosciuszki Street |

| Dreisenberg, Adam | 1913 C.K. Gimnazyum – graduated | born 24 May 1889 in Pilzno |

| Dunai,J | 1929 City Directory | Restaurants, 3 Maja Street |

| Dunaj, Jozef | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 9 Ulica Czackiego |

| Durat, Mozes | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Durst, Chaim & Eder, Mozes | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 19 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Dutkiewicz | 1929 City Directory | Notary |

| Dymnicka | 1929 City Directory | Doctor |

| Eckstein | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 10K | |

| Eckstein, Elias | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – Graduated | while serving in the military |

| Eder, Mozes | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 19 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Eder,M | 1929 City Directory | Textiles/Fabrics |

| Ehlenberg | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 10K | |

| Ehrenaum, Eugenia | 1928-1931, Class 3-7b, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Ehrenfreund | 1929 City Directory | Fruit wines, Kazimierza Wielkiego Street |

| Ehrenfreund,J | 1929 City Directory | Upholstery |

| Ehrlich | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Ehrlich, N & Zins, N | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 10 Ulica Nadbrzezna |

| Eibel, Edward | 1908 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4c | |

| Eibel, Edward | 1911 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 7a | |

| Eibel, Edward | 1912 C.K. Gimnazyum – graduated | born 15 Mar 1894 in Twierdza |

| Eibel, Josef | 1909 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b | |

| Eibenschutz, Ignacy | 1883 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 6 | |

| Eier | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Einhorn,A | 1929 City Directory | Kitchen Utensils, Rynek |

| Einziger, Natan - leather trader | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 5 Ulica Nowa |

| Einzinger | 1929 City Directory | Animal skins, Nowa Street |

| Einzinger, Isidore | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b | |

| Einzinger, Mozes | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Einzinger, Nathan | 1923 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Einzinger,Mozes - Kuntz’ clothes shop | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 5 Ulica Asnyka |

| Einzinger,W | 1929 City Directory | Tavern, Kosciuszki Street |

| Ekiert, Stanislaw | 1884 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b | |

| Elias, Abraham | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 7a | |

| Elias, Dawid | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Elias, Dawid | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 36 Ulica Jagielly |

| Elias, Dawid | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 3 Ulica Kazimierza Wielkiego |

| Elias, Natan – chimneys | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 7 Ulica Mickiewicza |

| Elias, Sala | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Elias, Sala | 1927, Class 7, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Elias, Sala Perla | 1928 B.Y.H.S.graduated | Born 23 Oct 1909 in Przemysl |

| Elijas, Irena | 1931, Class 5, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Eljas, Abraham | 1931 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Eljas, Helena | 1928-31, Class 4-7b, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Ellias,L | 1929 City Directory | Assorted goods, Wladyslawa Jagielly Street |

| Ellowitz,F | 1929 City Directory | Textiles/Fabrics, Rynek (main square), |

| Emer L and Kornfeld D | 1913 Business Directory | private financial institution |

| Emmer, Isaac | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 3c | |

| Emmer, Isaac | 1918 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4a | |

| Emmer, Izaak | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Emmer, Izaak - storehouse | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 12 Ulica Igielna |

| Emmer, Izaak & Melania | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 3 Ulica Florianska |

| Emmer,L | 1929 City Directory | Assorted goods, Igielna Street |

| Emner, Isaac | 1923 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Empty Property - Jewish owned | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 5 Ulica Szajnochy |

| Engel, Markus | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Engel, Markus - enamel pots | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 11 Ulica Wysoka |

| Engel,H | 1929 City Directory | Kitchen Utensils, Rynek |

| Engelhardt | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Engelhardt | 1929 City Directory | Fruit wines, Kosciuszki Street |

| Engelhardt, Izaak | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 4 Ulica Jagielly |

| Engelhart, Hinda | 1929 Graduated B.Y.H.S. | Born 26 Jan 1908 Rymanow |

| Engelhert, Hinda | 1926-9, Class 5-8, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Erlich,S | 1929 City Directory | Glass and porcelain |

| Faber, Cyla | 1931, Class 1, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Faber, Jozef | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 39 Ulica Jagielly |

| Faber, Jozef - stall keeper | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 5 Ulica Florianska |

| Faber,Ch | 1929 City Directory | Accessories, 3 Maja Street Accessories |

| Falek, Benjamin | 1908 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1c | |

| Falek, Benjamin | 1909 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2c | |

| Falek, Benjamin | 1911 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4b | |

| Falek, Benjamin | 1912 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5b | |

| Falek, Benjamin | 1916 C.K. Gimnazyum, student on military duty | Corporal |

| Falek, Benjamin, | 1913 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 6b | |

| Falek, Chaim | 1909 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 6K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Fallek, Chaim | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Fallek, Chaim - tavern | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 22 Ulica Ulaszowice |

| Fass | 1929 City Directory | Hairdresser |

| Fass, Isaac | 1927 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Fass, Wilhelm - barber shop (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 5 Ulica 3-go M`aja |

| Faust, Mozes - textiles | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 14 Ulica Igielna |

| Faust, Paulina | 1929 B.Y.H.S. graduated | Born 16 Dec 1909 Jaslo |

| Faust,M | 1929 City Directory | Textiles/Fabrics, Igielna |

| Feinchel, Gitla | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Feit, Salomon | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b | |

| Feit, Salomon | 1918 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b | |

| Feit, Salomon | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 3b | |

| Feldbradt, N - tailor | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 23 Ulica Basztowa |

| Fenichel (carrier) | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Fenichel, Bronislawa | 1923/1924, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Fenichel, Izaak | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 12 Ulica Targowica |

| Fensterblau, David | 1898-99 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 7/8 & graduated | |

| Fensterblau, David | 1892-94-95-97 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a/3a/4/6 | |

| Fensterblau, Felix | 1898 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 6 | |

| Fensterblau, Hoschea | 1894-95 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b/3b | |

| Fensterblau, Shie | 1893-97-99-00 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b/5/7/8 | |

| Feuer, M – Targowica | 1929 City Directory | Midwife, Targowica |

| Finder | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 6K | |

| Finder, Eugenia | 1923/1924, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Finder, Maurycy | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a | |

| Finder, Salomon | 1898 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1c | |

| Finder, Salomon | 1899-1902 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b/4b | |

| Fisch (baker) | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Fisch, Izaak & Windla - bakery | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 36 Ulica Szajnochy |

| Fisch, Mindla | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Fisch, Mindla - assorted goods | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 15 Ulica Szajnochy |

| Fisch, Mindla - tenement | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 16 Ulica Szajnochy |

| Fisch, Mozes? - bakery | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 2 Ulica Ulaszowice |

| Fisch,E | 1929 City Directory | Bakery, Kazimierza Wielkiego. |

| Fischer, Ludwik | 1884 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5 | |

| Fischer, N | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 39 Ulica Florianska |

| Fischer, Wladyslaw | 1887 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4b | |

| Fischler, David | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b | |

| Fleschar, Zofia | 1922/1923, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Forcher/Forscher, Jozef | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Forscher Josef | 1913 Business Directory | shoe polish |

| Forscher, Bernard | 1932 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Forscher, Bernard – industrialist from Jaslo | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Forscher, Jozef & Felicja - shoe shine factory “Luna” | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 7 Ulica Nowa |

| Forscher,J | 1929 City Directory | Shoe polish, Nowa Street |

| Forsteher, Bernard - shoemaker | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 3 Ulica Czackiego |

| Fraenkel | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Frankel and Stillman | 1909 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 41K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Frankel and Stillmann | 1908 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 21K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Frankel, Osiah | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a | |

| Frankel, Osiash | 1926 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Frankel, Oskar? - photo shop “Flora” & shoe shop “Bata” | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 5 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Frankel, Wolf | 1909 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 3a | |

| Frankel, Wolf | 1912 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5a | |

| Frankel, Wolf | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – Graduated | while serving in the military |

| Frankel,S | 1929 City Directory | Marmalade, Nowa Street |

| Frant, Izrael-assorted goods, haberdasher | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 4 Ulica Czackiego |

| Frant, Izreal | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Franzblau | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Franzblau Abraham | 1913 Business Directory | interior decoration |

| Franzblau, Chaya | 1926-9, Class 5-8, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Franzblau, Chaya Leah | 1929 Graduated B.Y.H.S. 1929 | Born 14 Jul 1911 Pilzno |

| Franzblau, Helena | 1925, Class 4, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Franzblau, Helena | 1927, Class 6, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Franzblau, Szyja – assorted goods | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 44 Ulica Florianska |

| Frenkel, Wolf | 1918 C.K. Gimnazyum – graduated | |

| Freund, Emil | 1882 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Freund, N - shoe shop (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 14 Rynek, Pirzeja |

| Freund,Ch | 1929 City Directory | Shoes, Rynek |

| Freund,M | 1929 City Directory | Shoes, Karmelicka |

| Frey,J | 1929 City Directory | Assorted goods, Czackiego Street |

| Friedweld, Elias | 1898 C.K. Gimnazyum – graduated | |

| Frisch,E | 1929 City Directory | Kitchen Utensils, Kosciuszki Street |

| Frisch,E | 1929 City Directory | Glass and porcelain, Kosciuszki Street |

| Frisner,L | 1929 City Directory | Hatter |

| Frohn Alexander | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – Graduated while serving in the army | |

| Fromowicz, Israel | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4a | |

| Fruhling, Stanislaw | 1908 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 6b | |

| Frunkeil,A | 1929 City Directory | Juice/Syrup factories, Szajnochy Street |

| Fuhrer, Hersch | 1898 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a | |

| Fuk, Jacob | 1887-90-91-92 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a/4a/5/6 | |

| Fuk, Jacob | 1894 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 & graduated | |

| Furst, Jacob | 1929 Jewish Teacher B.Y.H.S. | |

| Furst, Laura | 1930-1, Class 4-5, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Ganger, Osias | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Ganger, Osias - tavern | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 19 Ulica Targowica |

| Ganger,O | 1929 City Directory | Textiles/Fabrics, Rynek (main square), |

| Gans Napthali | 1913 Business Directory | interior decoration |

| Gans,I | 1929 City Directory | Painter |

| Gartenberg and Schreier | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 1380K | |

| Gartenberg and Schreier | 1929 City Directory | Oil industry, refinery |

| Gartenberg and Schreier | 1913 Business Directory | refinery, petroleum products |

| Gartenberg, David | 1893-94 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 6/7 | |

| Gartenberg, David | 1895 C.K. Gimnazyum – graduated | |

| Gastenberger and Schreirer | 1912 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation – 50K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Gawlow,Z | 1929 City Directory | salt |

| Gellar, Chaim | 1913 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b | |

| Geller, Israel | 1921 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Geller, Josef | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5a | |

| Geller, Josef | 1933 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Geller, Lotti | 1930 Graduated B.Y.H.S. 1930 | Born 4 Nov 1911 Iwonicz |

| Geller, Lotti | 1929, Class 7, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Geminder | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Geminder, Salamon | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 7 Ulica Kochanowskiego |

| Glaser, Anna - Restaurant | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 7 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Glaser, Jacob | 1904 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Glassman | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 62 Ulica Florianska |

| Glassman, Szymon? - carpenter | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 33 Ulica Szajnochy |

| Glassmann | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Glassner, Szymon | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Glassner, Szymon | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 16 Ulica Igielna |

| Glodfluss,M and Wistreich,S | 1929 City Directory | Sawmill, (steam) 3 Maja Street Jozef |

| Gluksman, Stanislaw | 1918 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2a | |

| Goetzler, Anna | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Goetzler, Mozes | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Goldberg, Jacob | 1893 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 3b | |

| Goldberg, Nathan | 1883-84-86-87 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a/2a/4/5 | |

| Goldblatt, Brucha | 1930, Class 3, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Goldblatt, Eugenia | 1927Graduated B.Y.H.S. | Born 21 Aug 1907 Jaslo |

| Goldblatt, Genowefa | 1925-7, Class 6-8, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Goldblatt, Gizela | 1920/1921, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Goldblatt, Ida | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Goldblatt, Ida | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 7 Ulica Kazimierza Wielkiego |

| Goldblatt, Ida - Weinberger, Leib | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 12 Ulica Basztowa |

| Goldblatt, Ida & Bruck N – cattle trader | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 23 Ulica Szajnochy |

| Goldblatt, Jutta | 1926-9, Class 5-8, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Goldblatt, Jutta | 1929 Graduated B.Y.H.S. | Born 23 Sep 1908 Jaslo |

| Goldblatt, Regina | 1931 Graduated B.Y.H.S. 1931 | Born 17 Oct 1911 Jaslo |

| Goldblatt, Regina | 1926-31, Class 3-8, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Goldblatt, Salomea | 1923/1924, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Goldblatt,Ch | 1929 City Directory | Timber, Kazimierza Wielkiego Street |

| Goldfaden | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Goldfaden, Natan - milk purchasing | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 6 Ulica Nowa |

| Goldflus, Leopold | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b | |

| Goldfluss and Wistreich | 1929 City Directory | Mills, 3 Maja Street (steam),. |

| Goldfluss, E. | 1909 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 10K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Goldfluss, Michal | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Goldfluss, Michal & Wistreich, Jakub - house | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 21 & 22 Ulica 3-go Maja |

| Goldman, Henryk | 1895 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1c | |

| Goldner | 1929 City Directory | Underwear, Kosciuszki Street |

| Goldner, Adolf - accessories shop (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 31 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Goldner, Berl | 1909 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5b | |

| Goldner, Berl | 1916 C.K. Gimnazyum – student killed on 7 May 1915 in Zurow near Lublin | (see note 1 below) |

| Goldschlag | 1904 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 10K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Goldschlag | 1905 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 10K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Goldschlag, Fryderyk | 1904 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b | |

| Goldschlag, Fryderyk | 1905 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b | |

| Goldschlag, Fryderyk | 1908 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5a | |

| Goldschlag, Fryderyk | 1909 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 6a | |

| Goldschlag, Fryderyk | 1911 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8a | |

| Goldschlag, Fryderyk – doctor from Lviv | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Goldschlag, Ludwik | 1908 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4c | |

| Goldschlag, Ludwik, | 1905 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1c | |

| Goldschlag, Zygmunt | 1908 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2c | |

| Goldschlag, Zygmunt | 1912 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5a | |

| Goldschlag, Zygmunt | 1913 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 6a | |

| Goldschlag, Zygmunt | 1916 C.K. Gimnazyum, student on military duty | sergeant, 1st Uhlan Regiment |

| Goldschlag, Zygmunt | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Goldschmidt | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Goldschmidt, Chana? | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 13 Ulica Koralewskiego |

| Goldstein | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation – 6K | |

| Goldstein M | 1913 Business Directory | firewood |

| Goldstein M | 1913 Business Directory | Building materials |

| Goldstein Samuel | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – Joined the army - class 8 | |

| Goldstein, B | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 10K | |

| Goldstein, Dawid | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Goldstein, Dawid - Clock shop of Schacht | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 34 Ulica Kazimierza Wielkiego |

| Goldstein, Ewa | 1925-7, Class 6-8, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Goldstein, Jacob | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b | |

| Goldstein, Jacob | 1928 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Goldstein, Salomon | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8b | |

| Goldstein, Salomon | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 3a | |

| Goldstein, Samuel | 1918 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2a | |

| Goldstein, Stefania | 1925-7, Class 4-7, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Goldstein, Stefania | 1928 B.Y.H.S. 1928 graduated | Born 8 Oct 1910 in Jaslo |

| Goldstein,B | 1929 City Directory | Timber |

| Goldstein,Ch | 1929 City Directory | Restaurants, Kazimierza Wielkiego Street |

| Golschlag, Deborah | 1911 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 120K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Golstein, Samuel | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – Graduated | while serving in the military |

| Gotlieb,S | 1929 City Directory | Oil products, Rynek |

| Gottlieb | 1916 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 6K | |

| Gottlieb Dr. | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 25K | |

| Gottlieb, Ignacy | 1913 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a | |

| Gottlieb, Ignacy | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5a | |

| Gottlieb, Ignacy | 1921 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Gottlieb, Ignacy – engineer from Jaslo | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Gottlieb, Krystyna | 1928-9, Class 1-2, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Gottlieb, Stan | 1929 City Directory | Lawyer |

| Gottlieb, Stanislaw – lawyer from Jaslo | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Gottlieb, Stanislaw (lawyer) | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Gotzler, Anna - Deli of Gotzler | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 3 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Gotzler, Mozes | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 6 Ulica Szajnochy |

| Gotzler, Mozes & Anna | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 11 Ulica Igielna |

| Gotzler,M | 1929 City Directory | Confectionery, 3 Maja Street |

| Graber, Dawid | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Graber, Markus - bakery | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 18 Ulica Koralewskiego |

| Grabschriff | 1929 City Directory | Dentist |

| Grabschrift | 1908 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 7K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Grabschrift | 1929 City Directory | Dentist technician, 3 Maja Street |

| Grabschrift (dentist) | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Grabschrift, Herman | 1905 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2a | |

| Grabschrift, Herman – dentist from Jaslo | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Grabschrift, Hermann | 1904 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a | |

| Grabschrift, N | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 6 Ulica Sobieskiego |

| Gross | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Gross, H - basket maker | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 12 Ulica Bednarska |

| Gross, Alfred - basket maker | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 11 Ulica Koralewskiego |

| Gross,M | 1929 City Directory | Baskets, Koralewskiego Street |

| Grunfeld, Malka | 1931, Class 4, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Grunfeld,J | 1929 City Directory | Mens’ Tailor, Bednarska Street |

| Grunfeld,O | 1929 City Directory | Shoes |

| Grunspann | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Grunspann Hersh | 1913 Business Directory | leather trade |

| Grunspann, N - tannery | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 3 Ulica Nadbrzezna |

| Gutwein | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Gutwein,M | 1929 City Directory | Textiles/Fabrics, Rynek (main square), |

| Gutwinski | 1929 City Directory | Notary |

| Guzik | 1929 City Directory | Ginger bread, Targowica |

| Guzik, N - pierikarz | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 15 Ulica Kazimierza Wielkiego |

| Haas (prior owner) timber storage | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 18 Ulica Basztowa |

| Haas, | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Haas, Elias | 1909 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 20K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Haas, Elias | 1911 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation - 3K | (Austro-Hungarian Krone) |

| Haas, Herman | 1933 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Haas, Isaac | 1928 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Haas, Izaak | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 19 Ulica Florianska |

| Haas, N | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 11 Ulica Florianska |

| Haas, Roza | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Haas, Roza | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 6 Ulica Florianska |

| Haas, Salomea | 1923/1924, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Haas, Zygmunt | 1894 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 & graduated | |

| Haas,L | 1929 City Directory | Timber |

| Haas,L | 1929 City Directory | Timber, Florianska Street |

| Haber, Mozes | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Haber, Mozes - carriages, cab driver | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 4 Ulica Stroma |

| Haber, Mozes? | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 74 Ulica 3-go Maja |

| Haber, Natan – tailor | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 9 Ulica Stroma |

| Haber,M | 1929 City Directory | Ladies’ Tailor, Stroma Street |

| Habermann Benjamin | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4b | |

| Hagel | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Hagel, N. – textiles (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 13 Rynek, Pirzeja |

| Hagel,H | 1929 City Directory | Textiles/Fabrics |

| Halberstamm (rabbi) | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Hallaman,A | 1929 City Directory | Tavern, Florianska Street |

| Handler, Cecylia | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Handler, Cecylia | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 21 Ulica Basztowa |

| Handler, Cecylia - tavern | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 1 Ulica Florianska |

| Harnwolf, Artur | 1897 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 7 | |

| Heffner, N - transport/freight | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 39 Szajnochy |

| Heilpern, Aron | 1905 C.K. Gimnazyum – Latin Teacher | |

| Heller, Abraham | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Heller, Abraham - horse trader | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 10 Ulica Szajnochy |

| Heller, Emilia | 1929, Class 5a, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Heller, Etka | 1926-9, Class 5-8, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Heller, Etka | 1929 Graduated B.Y.H.S. | Born 20 Jun 1911 Kowalowy |

| Heller, Salomea | 1928-31, B.Y.H.S. class 3-6 | |

| Heller, Salomon | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5a | |

| Heller, Salomon | 1918 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 6b | |

| Heller, Salomon | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 7 | |

| Heller,M | 1929 City Directory | Horse Trader, Basztowa |

| Hergesell | 1916 C.K. Gimnazyum – donation – 6K | |

| Hergessel, Alfred | 1912 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a | |

| Herz, Adam | 1887-90-92 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b/4b/6 | |

| Herz, Baruch | 1886 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 3b | |

| Herz, Boruch | 1890 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 6 | |

| Herz, Bronislaw | 1887 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4a | |

| Herz, Eisig | 1894 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 & graduated | |

| Herzig, Herman | 1884-1924 | 1905 Stones in the Cemetery (see KehilaLinks page) |

| Herzig, Jakob | 1929 City Directory | Lawyer |

| Herzig, Jakub (lawyer) | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Heumann, Henryk | 1884 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4 | |

| Hibl, Ludwik | 1892 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4 | |

| Hibl, Ludwik | 1897 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Hicner | 1929 City Directory | Doctor |

| Hicner | 1929 City Directory | Doctor |

| Hirsch, Rivka | 1930-1, Class 5-6, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Hochhauser, Frida | 1929, Class 8, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Hochhauser, Fryda | 1929 B.Y.H.S.graduated | Born 8 Apr 1909 Nowy Sacz |

| Hoffert and Hollander | 1929 City Directory | Colonial Goods, Kazimierza Wielkiego Street |

| Hoffert, Elias | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Hoffert, Elias - soda water factory (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 27 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Hoffman, Akiva | 1905 C.K. Gimnazyum – religion teacher | |

| Hoffman, Akiwa(teacher) | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Hoffman, Bertha | 1922/1923, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Hoffman, Jacob | 1908 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b | |

| Hoffman, Jacob | 1909 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b | |

| Hoffman, Jacob – MP from Warsaw | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Hoffman, Joel | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b | |

| Hoffman, Miriam | 1920/1921, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Hoffman, Simon | 1908 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1b | |

| Hoffman, Simon | 1912 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5b | |

| Hoffman, Simon | 1916 C.K. Gimnazyum, student died on 11 June 1915 in Buczacz | (see note 1 below) |

| Hoffman, Simon | 1916 C.K. Gimnazyum, student on military duty | Cadet |

| Hoffmann, Simon | 1909 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b | |

| Hofman, Israel | 1913 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 1a | |

| Holander, N | 1930s: Name from Booklet (Above) | “Jewish Community in Old Yaslo” |

| Hollander and Hoffert | 1929 City Directory | Colonial Goods, Kazimierza Wielkiego Street |

| Hollander, Izaak | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 7 Ulica Stroma |

| Hollander,A | 1929 City Directory | Eggs |

| Hornberger, Josef | 1909 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2b | |

| Hornberger, Josef | 1913 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 5b | |

| Hornberger, Josef | 1916 C.K. Gimnazyum, student awarded Military decoration | |

| Hugo, Dr Steinhaus - colonial goods | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 2 Rynek, Pirzeja |

| Hupnicki | 1929 City Directory | Vetinary Doctor |

| Husar, H Slowackiego St | 1929 City Directory | Midwife, Slowackiego Street |

| I. Haas | 1929 City Directory | Timber |

| Ingber, Braindla | 1925, Class 7, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Ingber, Braindla | 1926, Class 8 B.Y.H.S. | |

| Ingber, Braindla | 1926 Graduated B.Y.H.S. 1926 | Born 28 July 1907 Jaslo |

| Ingber, Jacob | 1917 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 2 | |

| Ingber, Jacob | 1918 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 3b | |

| Ingber, Jacob | 1919 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 4b | |

| Ingber, Jacob | 1923 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Ingber, Moses | 1928 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Ingber, Regina | 1930 Graduated B.Y.H.S. 1930 | Born 7 Sep 1909 Jaslo |

| Ingber, Regina | 1929, Class 7, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Jaklinski,K | 1929 City Directory | Tobacco goods, Koralewskiego Street |

| Jakub Schorr, Jakub | 1929 City Directory | Doctor |

| Jakubowicz, Meilech – assorted goods | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 13 Ulica Kilinskiego |

| Jamner, Moses | 1927 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Jamner, Moses | 1938 C.K. Gimnazyum – celebration attendee | 70th anniversary of school |

| Jamner, Wolf | 1929 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 6a | |

| Jamner, Wolf | 1932 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 8 | |

| Jarymowicz Emmanel | 1913 Business Directory | Cement Factory |

| Jugendfein, Jan | 1878 C.K. Gimnazyum - graduated | |

| Jugendfein, Karol | 1878 C.K. Gimnazyum – class 6 | |

| Jurasz | 1929 City Directory | Lawyer |

| Jurys | 1929 City Directory | Sausages, meat products, Slowackiego Street |

| Jurys,E | 1929 City Directory | Shoes |

| Jurys,J | 1929 City Directory | Funeral homes |

| Jurys,K | 1929 City Directory | Funeral Homes, Zielona Street |

| Just, Osias - watch maker (tenant) | 1939: Memoirs of Jaslo | 34 Ulica Kosciuszki |

| Just,B | 1929 City Directory | Jewelry |

| Kachlik,E | 1929 City Directory | Assorted goods, Wladyslawa Jagielly Street |

| Kaczkowska, Anna | 1925-6, Class 6-7, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Kaczkowska, Maria | 1925-6, Class 4/6, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Kaczkowska, Natalia | 1923/1924, B.Y.H.S. | |

| Kaczkowska, Olga | 1925 Graduated B.Y.H.S., class of 1925 | Born 11 May 1907 in Jaslo |

| Kaczkowska, Olga | 1925, Class 8,B.Y.H.S. | |

| Kaczkowska, Zofia | 1930, Class 5, B.Y.H.S. | |