Between 1938 and 1941, Jews in Hungary were subject to

anti-Semitic legislation resembling that of Germany's

Nuremberg laws. Jews, defined in racial terms, were

removed from public and economic life. In 1941,

election laws were revised, and 109 local Jews in

Körmend were disenfranchised, and the local council

membership of 8 Jews was terminated.

Prior to 1944, Jews were generally not subject to deportations, though adult Jewish men were "drafted" for forced labor service.

German forces occupied Hungary on March 19, 1944. In April, all Jews except those in Budapest were ordered into ghettos. Generally, Jews from the countryside were sent to ghettos in larger urban areas. According to regulations, ghettos were to be established in all towns and cities with populations greater than 10,000. In practice, county officials were given some leeway where to establish ghettos. There were seven ghettos in Vas megye, including one in Körmend.

Prior to the creation of the ghetto, Jews in Körmend had been subject to increasing restrictions. For example, they could only visit the market between 8:00 a.m. and 9:00 a.m. and stores only between 9:00 a.m. and 10:00 a.m. Other restrictions included being permitted to visit the bathhouse only one morning per week and being prohibited from leaving their apartments between the hours of 7:00 p.m. and 7:00 a.m. Between March and May 1944, the Neolog Jewish Community Association, the Chevra Kadish, the Jewish Women's Association, and the Jewish Medical Aid Association were first registered, then forced to disband. The real estate and other assets of these organizations were confiscated. In April, Jews were forced to close their businesses. Their goods and furnishings were confiscated, and livestock and perishable items were sold. Inventories of Jewish owned factories and artwork confiscated from Jews were drawn up. As an example of the enthusiasm with which the local Hungarian authorities performed their duties, Jewish radios were confiscated even before the official decree was issued.

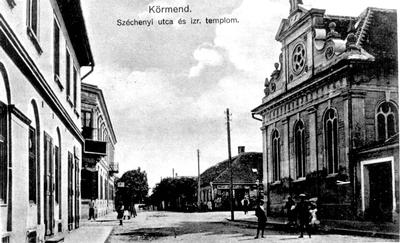

The ghetto in Körmend was established on May 9th, 1944, bounded by Szóchenyi, Rába, Gróf Apponyi and Dienes Lajos streets and including the synagogue. This necessitated the movement of non-Jews from their properties within the boundaries as well as movement of Jews outside the boundaries into the ghetto. Between May 10-12, Jews from neighboring villages and hamlets including Csákánydoroszló, Egyházasrádóc, Ivánec, Molnaszecsõd, Nagyrákos, Örimagyarosd and Szarvaskend were brought to the Körmend ghetto. In all, the ghetto held over 300 Jews. By May 20th, the ghetto was surrounded by a two meter high wooden fence with two closed and guarded gates, one for pedestrian traffic and the other for vehicular traffic, built and paid for by its inhabitants. After that date, Jews were only allowed to leave the ghetto with passes signed by the police. A generic ghetto pass was drawn up allowing the holder to leave only through the Szechenyi utca gate, travel by the most direct route and return as soon as they had finished their task. There was to be no dawdling. The pass was non-transferable and was checked by policemen at the ghetto gate. ¹

On May 23rd, thirty one passes were granted, for about 10% of the ghetto population. A team of four married women along with two men whose task was to carry purchases, were granted passes to shop during the restricted hours and thereby provide food for the ghetto inhabitants. The five-man Jewish Council were also granted passes to leave the ghetto on official business. In addition, two men were permitted to leave to collect and deliver mail and purchase newspapers and medicines. Some professionals and highly skilled workers, such as doctors, tinsmiths, plumbers, and steam saw mill workers, could be granted passes to continue their work among non-Jews. Others granted passes to work included clerks, shoemakers, tailors, haulers, dress fitters, ladder menders and watchmen.² In the interest of expropriating Jewish property and businesses, some Jews were issued passes in order to assist with inventory and to settle accounts with suppliers. Other passes were granted in order to satisfy the need for temporary labor on an ongoing or single day basis by local army and paramilitary units, the city administration and even individuals. For example, a team of twelve young women worked 13 hours a day in the Prince Batthyány gardens and a team of five older women worked in another garden. Five women received passes for daily farm work. On May 27, a group of 20 was sent to Army headquarters in Celldomölk to carry timber from a wood on the outskirts of the village to the railway station in Nadasd.³ Eventually, altogether over 60 passes were granted. Even children could be issued passes. Twelve teenaged boys between the ages of 12 and 19 had the rather unusual assignment of collecting mulberry leaves (working 11-12 hours a day) to feed 51,000 silk worms being raised by the paramilitary youth organization Levente, presumably to produce parachute silk. Their group was later augmented by an additional 11 year old boy and nine girls between the ages of 9 and 14.

There was also limited traffic by non-Jews into the ghetto such as pastors to minister to converts, painters and electricians for building repairs as well as teachers and barbers.

On June 12, all Jewish men (including converts) born between 1896 and 1926 (aged 18 to 48) were called up as part of an ongoing mobilization for service in labor battalions. These labor battalions were usually sent to the Eastern Front, where they suffered high casualty rates. Also in early June, 15 Jews were transferred to Kõszeg.

Sunday, June 18th, was the last full day of the ghetto's existence. Despite a rumor that if you worked very hard you would not come to any harm, on Monday morning, June 19th, just over a month after the creation of the ghetto, the remaining Jews of Körmend were marched out the main gate. Carrying suitcases and bundles of possessions and escorted by gendarmes, they continued on foot through town to the railway station, where they were transported to the ghetto in Szombathely. By the afternoon, there were no Jews left.

The concentration and entrainment center in Szombathely was on the grounds of the Mayer Machine Works, a factory that had been idle for nearly 20 years. It was chosen based on its accessibility to the ghetto, its size, and because its rail facilities were connected with the city's freight station. The first Jews that arrived in Szombathely were dumped into factory buildings with broken roofs and broken windows. Subsequent groups of arrivals were forced to settle in the courtyard under the open sky. Compounding their miserable situation was the lack of water, electricity and insufficient numbers of toilets. Water was only occasionally delivered by a municipal watering truck, and hot food was delivered only twice, sufficient for only a few hundred people, not the several thousands there. Because of the inhumane conditions and inadequate provisions, the number of deaths rose daily, especially among those over 60 years of age.

The liquidation of the entrainment center began on July 3rd, though the vast majority were deported on the following day; over 3,000 people crammed into 47 cattle cars. On July 5, 1944 they passed through Kassa, Slovakia on their way to Auschwitz. Many perished or went mad along the way because of the lack of food and water. Some of the men were taken to the forced labor camp at Muhldorf near Munich, where the vast majority perished.

The synagogue established in 1888 and located on the corner of Szechenyi and Dienes Streets was used as a military warehouse during WWII. On March 27, 1945, the synagogue was set afire and destroyed. After the war, a private residence was built on the site.

Perhaps 20-30 individuals survived the Shoah. After the war, survivors re-established the community but by 1960 they had dispersed.

In 2004, as part of a country-wide commemoration, a Holocaust memorial was erected. The memorial was a work by local ceramic artist Ildikó Polgar.

Prior to 1944, Jews were generally not subject to deportations, though adult Jewish men were "drafted" for forced labor service.

German forces occupied Hungary on March 19, 1944. In April, all Jews except those in Budapest were ordered into ghettos. Generally, Jews from the countryside were sent to ghettos in larger urban areas. According to regulations, ghettos were to be established in all towns and cities with populations greater than 10,000. In practice, county officials were given some leeway where to establish ghettos. There were seven ghettos in Vas megye, including one in Körmend.

Prior to the creation of the ghetto, Jews in Körmend had been subject to increasing restrictions. For example, they could only visit the market between 8:00 a.m. and 9:00 a.m. and stores only between 9:00 a.m. and 10:00 a.m. Other restrictions included being permitted to visit the bathhouse only one morning per week and being prohibited from leaving their apartments between the hours of 7:00 p.m. and 7:00 a.m. Between March and May 1944, the Neolog Jewish Community Association, the Chevra Kadish, the Jewish Women's Association, and the Jewish Medical Aid Association were first registered, then forced to disband. The real estate and other assets of these organizations were confiscated. In April, Jews were forced to close their businesses. Their goods and furnishings were confiscated, and livestock and perishable items were sold. Inventories of Jewish owned factories and artwork confiscated from Jews were drawn up. As an example of the enthusiasm with which the local Hungarian authorities performed their duties, Jewish radios were confiscated even before the official decree was issued.

The ghetto in Körmend was established on May 9th, 1944, bounded by Szóchenyi, Rába, Gróf Apponyi and Dienes Lajos streets and including the synagogue. This necessitated the movement of non-Jews from their properties within the boundaries as well as movement of Jews outside the boundaries into the ghetto. Between May 10-12, Jews from neighboring villages and hamlets including Csákánydoroszló, Egyházasrádóc, Ivánec, Molnaszecsõd, Nagyrákos, Örimagyarosd and Szarvaskend were brought to the Körmend ghetto. In all, the ghetto held over 300 Jews. By May 20th, the ghetto was surrounded by a two meter high wooden fence with two closed and guarded gates, one for pedestrian traffic and the other for vehicular traffic, built and paid for by its inhabitants. After that date, Jews were only allowed to leave the ghetto with passes signed by the police. A generic ghetto pass was drawn up allowing the holder to leave only through the Szechenyi utca gate, travel by the most direct route and return as soon as they had finished their task. There was to be no dawdling. The pass was non-transferable and was checked by policemen at the ghetto gate. ¹

| photos

showing the ghetto fence in Körmend |

On May 23rd, thirty one passes were granted, for about 10% of the ghetto population. A team of four married women along with two men whose task was to carry purchases, were granted passes to shop during the restricted hours and thereby provide food for the ghetto inhabitants. The five-man Jewish Council were also granted passes to leave the ghetto on official business. In addition, two men were permitted to leave to collect and deliver mail and purchase newspapers and medicines. Some professionals and highly skilled workers, such as doctors, tinsmiths, plumbers, and steam saw mill workers, could be granted passes to continue their work among non-Jews. Others granted passes to work included clerks, shoemakers, tailors, haulers, dress fitters, ladder menders and watchmen.² In the interest of expropriating Jewish property and businesses, some Jews were issued passes in order to assist with inventory and to settle accounts with suppliers. Other passes were granted in order to satisfy the need for temporary labor on an ongoing or single day basis by local army and paramilitary units, the city administration and even individuals. For example, a team of twelve young women worked 13 hours a day in the Prince Batthyány gardens and a team of five older women worked in another garden. Five women received passes for daily farm work. On May 27, a group of 20 was sent to Army headquarters in Celldomölk to carry timber from a wood on the outskirts of the village to the railway station in Nadasd.³ Eventually, altogether over 60 passes were granted. Even children could be issued passes. Twelve teenaged boys between the ages of 12 and 19 had the rather unusual assignment of collecting mulberry leaves (working 11-12 hours a day) to feed 51,000 silk worms being raised by the paramilitary youth organization Levente, presumably to produce parachute silk. Their group was later augmented by an additional 11 year old boy and nine girls between the ages of 9 and 14.

There was also limited traffic by non-Jews into the ghetto such as pastors to minister to converts, painters and electricians for building repairs as well as teachers and barbers.

On June 12, all Jewish men (including converts) born between 1896 and 1926 (aged 18 to 48) were called up as part of an ongoing mobilization for service in labor battalions. These labor battalions were usually sent to the Eastern Front, where they suffered high casualty rates. Also in early June, 15 Jews were transferred to Kõszeg.

Sunday, June 18th, was the last full day of the ghetto's existence. Despite a rumor that if you worked very hard you would not come to any harm, on Monday morning, June 19th, just over a month after the creation of the ghetto, the remaining Jews of Körmend were marched out the main gate. Carrying suitcases and bundles of possessions and escorted by gendarmes, they continued on foot through town to the railway station, where they were transported to the ghetto in Szombathely. By the afternoon, there were no Jews left.

|

| Körmend;

Deportation of the Jews, 1944 Rákoczi Ferenc utca photo courtesy of the Hungarian National Museum and used with permission by Yad Vashem |

The concentration and entrainment center in Szombathely was on the grounds of the Mayer Machine Works, a factory that had been idle for nearly 20 years. It was chosen based on its accessibility to the ghetto, its size, and because its rail facilities were connected with the city's freight station. The first Jews that arrived in Szombathely were dumped into factory buildings with broken roofs and broken windows. Subsequent groups of arrivals were forced to settle in the courtyard under the open sky. Compounding their miserable situation was the lack of water, electricity and insufficient numbers of toilets. Water was only occasionally delivered by a municipal watering truck, and hot food was delivered only twice, sufficient for only a few hundred people, not the several thousands there. Because of the inhumane conditions and inadequate provisions, the number of deaths rose daily, especially among those over 60 years of age.

The liquidation of the entrainment center began on July 3rd, though the vast majority were deported on the following day; over 3,000 people crammed into 47 cattle cars. On July 5, 1944 they passed through Kassa, Slovakia on their way to Auschwitz. Many perished or went mad along the way because of the lack of food and water. Some of the men were taken to the forced labor camp at Muhldorf near Munich, where the vast majority perished.

The synagogue established in 1888 and located on the corner of Szechenyi and Dienes Streets was used as a military warehouse during WWII. On March 27, 1945, the synagogue was set afire and destroyed. After the war, a private residence was built on the site.

Perhaps 20-30 individuals survived the Shoah. After the war, survivors re-established the community but by 1960 they had dispersed.

In 2004, as part of a country-wide commemoration, a Holocaust memorial was erected. The memorial was a work by local ceramic artist Ildikó Polgar.

|

||

| Sunday,

19 June 2005 11:30 a.m. Holocaust memorial remembering

victims of the Körmend Holocaust |

Holocaust

memorial

by Ildikó Polgar |

|

|

|

| Synagogue

plaque; mounted 1 Jul 1990 Left side: "Here began the Ghetto. From here left 384 Jews to the death camps. Right side: "At this place stood the Synagogue of the Körmend Jewish community. It was built in 1865 in the classical style. It burned down on March 28, 1945. Below: "Erected in memory by the Town Council of the City of Körmend" |

Memorial

list

of those deported to Auschwitz |

Street sign. This street was in the Körmend ghetto. It shows the old and new names.

Footnotes:

¹. Traces of the Holocaust: Journeying in and out of the Ghettos by Tim Cole, page 72

². ibid.

³. ibid. page 79

Return to Körmend main page

© Copyright 2008 Judy

Petersen

|