Kolonja Izaaka

History, Jewish Agriculture and International Support

Kolonja Izaaka is an example of a first

wave of Jewish agricultural development in Tsarist Russia. As a result

of the partitions of Poland beginning in 1791, vast numbers of Jews of

eastern Poland found themselves living on the western

outskirts of Imperial Russia. In that year, Catherine the Great issued

an edict confining Jews to the Pale of Settlement -

a

thin strip of land roughly reconstituting the former

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and including what are now Lithuania,

Eastern Poland, Belarus, Bessarabia and Ukraine.

In 1807, a statute prohibited Jews from holding any leases on land. Thus barred from agriculture, Jews instead eked out their livings as tradespeople, shopkeepers, moneylenders, scholars, artisans, etc. Food production was the province of wealthy landowners, with labor provided by the serfs that were beholden to them.

In 1835, an edict was issued placing additional limitations on the settlement and movement of Jews. However the edict also relaxed the land ownership restrictions, permitting Jews to settle on government land for purposes of agriculture, apparently to further a government policy of developing airable land to shore up Russia's food production. In 1848, 158 Jewish families settled on government lands, and this wave of settlement continued until the western Russian governments abandoned this policy in 1864.

This first wave of Jewish agricultural settlements included Avramowo, Ivaniki, Izraelska, Galilejska, Dovgalishok, Dubrowo, Lejbishok, Leipun, Sinajska, Pawlowa, Kurenetz and Kolonja Izaaka (possibly called Kolonja Odelsk at its inception).

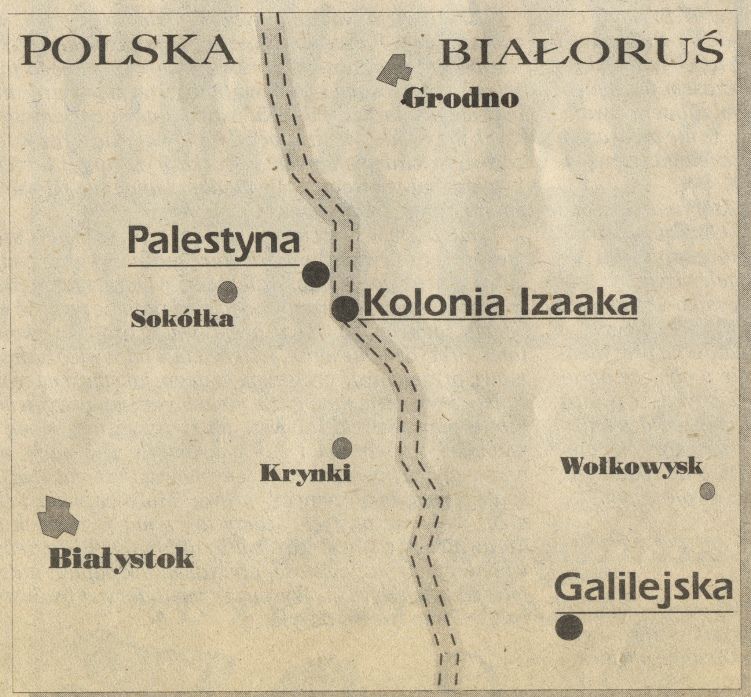

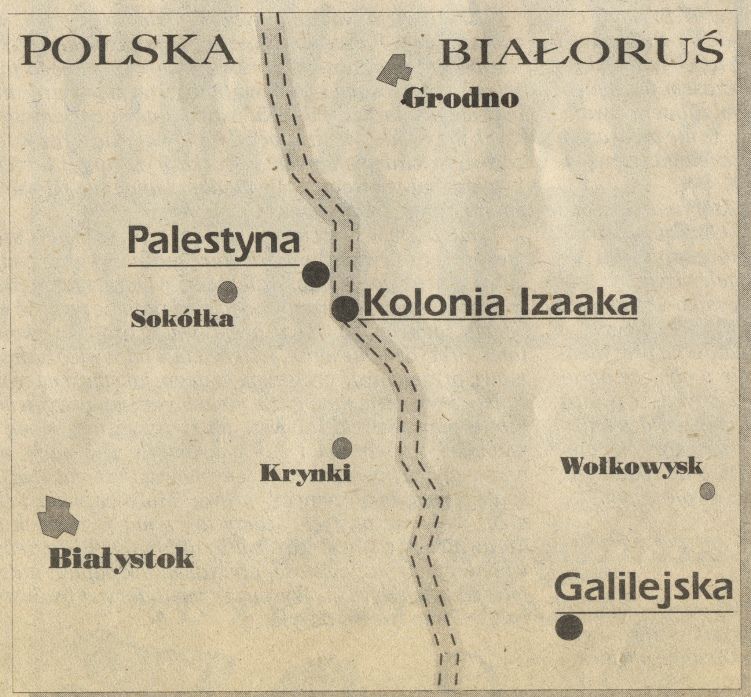

Kolonja Izaaka was founded in 1849, when the provincial government of Grodno offered a tract of land 1.5 km southwest of Odelsk to poor local Jews, in the hopes that they would be motivated by the prospect of land ownership and the independence it might bring. The land was sandy and rocky, and took years - and the support of Jews abroad - to become productive.

Twenty-six Jewish families staked their claim. During the first decades of the colony's existence, the land alone was insufficient to support the landowners; the Jews of Kolonja Izaaka often engaged in trades in Krynki, Sokolka and Bialystok, and left tenants to cultivate the land.

Like many colonies, Kolonja Izaaka began to receive support from Jewish organizations in Russia and abroad. The Organization for the Rehabilitation of Jews through Training (ORT) was founded in 1880 and offered training opportunities for Jewish farmers. The Paris-based Jewish Colonization Association (JCA) granted vast sums of money belonging to the Baron de Hirsch to Jewish colonies in Eastern Europe, South America and the United States, beginning in 1891, to support Jewish independence. Kolonja Izaaka was among them. With the help of ORT and JCA, Kolonja Izaaka became a strong local producer of grains, legumes and orchard fruit.

World War I and the subsequent Russian Revolution interrupted the outside support received by Izaaka and other colonies. Redrawing of borders left Kolonja Izaaka as part of the Bialystok District of the newly reunified Poland. The JCA was forced to scramble to create a new infrastructure to work with the newly created Polish government. According to a document published by the JCA in 1931 in honor of the centenary of the birth of Baron de Hirsch, JCA support did manage to continue in the region, including helping settlements expand their cultivation of fruit trees and, in 1926, introducing bee-keeping, which we know through Salit to have been part of Kolonja Izaaka's economy. Kolonja Izaaka, referred to as Isakowo, was specifically mentioned in the portion of the document describing the JCA's work in Poland in the 1920s:

Despite the seeming prosperity of the 1920s, Kolonja Izaaka fell into the same economic depression as the rest of Europe in the 1930s. At first the colony received loans from ORT and JCA to help with their large tax burden, but eventually credit was halted. While conditions were undoubtedly more difficult in the remainder of the 1930s, we have no testimony regarding them. The Jewish colonists perished and their homes burned at the hands of the Nazis in 1942 and the Christians were moved to Odelsk by the Soviet government after the War.

Photo at top of page: a barn in the nearby shtetl of Krynki. Photo by Irwin Keller, 2007. Map courtesy of Tomasz Wisniewski.

Copyright © 2008 Irwin Keller

In 1807, a statute prohibited Jews from holding any leases on land. Thus barred from agriculture, Jews instead eked out their livings as tradespeople, shopkeepers, moneylenders, scholars, artisans, etc. Food production was the province of wealthy landowners, with labor provided by the serfs that were beholden to them.

In 1835, an edict was issued placing additional limitations on the settlement and movement of Jews. However the edict also relaxed the land ownership restrictions, permitting Jews to settle on government land for purposes of agriculture, apparently to further a government policy of developing airable land to shore up Russia's food production. In 1848, 158 Jewish families settled on government lands, and this wave of settlement continued until the western Russian governments abandoned this policy in 1864.

This first wave of Jewish agricultural settlements included Avramowo, Ivaniki, Izraelska, Galilejska, Dovgalishok, Dubrowo, Lejbishok, Leipun, Sinajska, Pawlowa, Kurenetz and Kolonja Izaaka (possibly called Kolonja Odelsk at its inception).

Kolonja Izaaka was founded in 1849, when the provincial government of Grodno offered a tract of land 1.5 km southwest of Odelsk to poor local Jews, in the hopes that they would be motivated by the prospect of land ownership and the independence it might bring. The land was sandy and rocky, and took years - and the support of Jews abroad - to become productive.

Twenty-six Jewish families staked their claim. During the first decades of the colony's existence, the land alone was insufficient to support the landowners; the Jews of Kolonja Izaaka often engaged in trades in Krynki, Sokolka and Bialystok, and left tenants to cultivate the land.

Like many colonies, Kolonja Izaaka began to receive support from Jewish organizations in Russia and abroad. The Organization for the Rehabilitation of Jews through Training (ORT) was founded in 1880 and offered training opportunities for Jewish farmers. The Paris-based Jewish Colonization Association (JCA) granted vast sums of money belonging to the Baron de Hirsch to Jewish colonies in Eastern Europe, South America and the United States, beginning in 1891, to support Jewish independence. Kolonja Izaaka was among them. With the help of ORT and JCA, Kolonja Izaaka became a strong local producer of grains, legumes and orchard fruit.

World War I and the subsequent Russian Revolution interrupted the outside support received by Izaaka and other colonies. Redrawing of borders left Kolonja Izaaka as part of the Bialystok District of the newly reunified Poland. The JCA was forced to scramble to create a new infrastructure to work with the newly created Polish government. According to a document published by the JCA in 1931 in honor of the centenary of the birth of Baron de Hirsch, JCA support did manage to continue in the region, including helping settlements expand their cultivation of fruit trees and, in 1926, introducing bee-keeping, which we know through Salit to have been part of Kolonja Izaaka's economy. Kolonja Izaaka, referred to as Isakowo, was specifically mentioned in the portion of the document describing the JCA's work in Poland in the 1920s:

En

1927 et 1928, l'activité de l'oeuvre se développe dans

tous les domaines sur une échelle de plus en plus vaste. La

prospérité des colonies augmente et l'on peut

déjà

réaliser dans certains centres des mesures

d'intérêt général. A Dubrowa, Dowgeliszki,

Isakowo et Iwaniki, les routes, jusqu'alors impraticable en certaines

saisons, sont aménagées et bordées d'arbres.

From this we learn that the single road, or "allée" so fondly recalled

in remembrances of Kolonja Izaaka, was paved in 1927 or 1928, and that

the poplars lining it, still visible in satellite photos, were planted

at the same time, with the help of Baron de Hirsch funds.Despite the seeming prosperity of the 1920s, Kolonja Izaaka fell into the same economic depression as the rest of Europe in the 1930s. At first the colony received loans from ORT and JCA to help with their large tax burden, but eventually credit was halted. While conditions were undoubtedly more difficult in the remainder of the 1930s, we have no testimony regarding them. The Jewish colonists perished and their homes burned at the hands of the Nazis in 1942 and the Christians were moved to Odelsk by the Soviet government after the War.

Photo at top of page: a barn in the nearby shtetl of Krynki. Photo by Irwin Keller, 2007. Map courtesy of Tomasz Wisniewski.

Copyright © 2008 Irwin Keller