Compiled by Martin Davis © 2010- 2017

Click to enlarge photos

Living in Kamenets-Podolsk

The pre Second World War Jewish community of Kamenets was large enough to maintain numerous Jewish institutions. In its heyday, the Jewish adult population constituted almost 50% of the total population of the city (that is 23,430 people in 1913). The Jewish way of life in Kamenets, prior to the Bolshevik suppressions of 1926 held an attraction for the population; which only the systematic low level Anti Semitism (much of it officially inspired) could sour. In that context it is hardly surprising that many of the Jewish residents of Kamenets chose to remain in their home-town’ , rather than emigrate either to Palestine or to the new world. This goes some way to explaining why my great grandparents - Anja (Hannah) and Avrum-Meyer Leiferman - tried to settle in the UK but returned to Kamenets.Currents of History

Outwardly, the family appeared as a traditional observant Jewish extended household but, like almost every other family within the community, they were caught up in the currents of history. In 1895, my grandfather (Mordecai-Moshe Leiferman) received his letter from the Imperial Russian Army conscription board, requiring him to report for 5 years of compulsory military service. The requirement was a leftover from the early to mid 1800’s when one male Jew from each family had been forced to undertake 25 years of military conscription and many Jewish boys had been effectively kidnapped and forced into a lifetime’s army servitude. The aim was to ‘Russify’ the Jews; and in that earlier period obliterate their knowledge of family and religion. There are many stories of Jewish men - understandably - trying to find ways to avoid such conscription - such as changing their names and ‘disappearing’ to avoid this Gehenna. My grandfather had agreed with his family that he would go through with it as he was capable of undertaking the physical hardship and it would be a protection for the family. He ceased his studies at the Bet Midrash under Reb Yehuda Goldschmidt (later to become his father-in-law) and reported to the enlistment centre - probably in Kitaigorod, a town near Kamenets - and served as a Sapper in the 100th Division of the 13th Regiment of the Engineers of the Tzar’s Army. His only remembered comment about his military service was that when asked by one of his daughters what he did in the army, he responded with humour and a twinkle in his eye, “I was a cook”. Finally the majority of the members of the family decided that they would have to go. This presented a double difficulty for my grandfather; he was both betrothed to marry (Etiyeh Golda Goldschmidt - my grandmother) and was also obliged to remain on call as a reserve soldier for the army. After discussion with my grandmother and both sides of the family, a marriage was ‘contracted’ according to the the religious practices that the family followed. Then the majority of the family fled Kamenets, never to return. Those of the extended Leiferman family who did remain, including Zeidel Leiferman and their children, later experienced hardship and poverty. No members of the extended family, or their friends, who remained in Kamenets are known to have survived the Shoah. Martin Davis

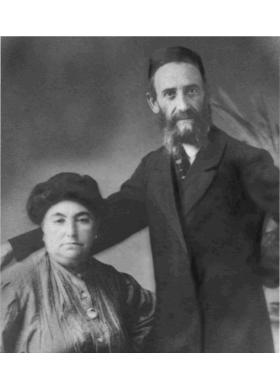

Avrum-Meyer and Anja (Hannah)

Leiferman circa 1895

A Jewish run inn Ukraine circa 1845 - note the social mix of

Ukrainian and Jewish people.

Frima (nee Leiferman) and Aharon

Reichman c 1895

Anja and Avrum-Meyer, who had three children (Zeidel, Frima and

Mordecai-Moshe), owned an inn and were licensed to sell both alcohol

and tobacco. The latter license was apparently very valuable and

enabled the whole family to live from the income generated from the inn

and to develop an associated small business factoring wine and corn.

From our family tradition I would say that the business side of the ‘firm’

was undertaken by the women - it is very clear that during the period up

until 1900 my great aunt and great grandmother were in charge of the

business whilst the men of the family did the farm trading, labouring and

the (most importantly) the studying and praying.

In reality ordinary soldiers in the Imperial Russian army were on semi-

starvation rations and much of what food they did have was trayf, that is

not kosher (so for any observant Jew both a physical and moral challenge

to eat and impossible to cook).

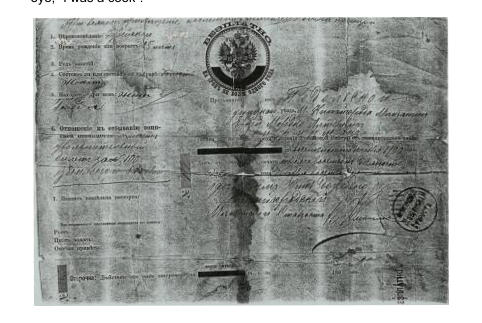

His army record shows that he completed his service without punishment

and received an honourable discharge. His discharge certificate, which

also served as an internal passport, gave him and his direct family the right

to live in any part of the Russian Empire and to travel to, and cross, its

borders and demonstrated to the authorities that he had achieved the

status of a ‘citizen Jew’ - as the certificate testifies!

Leaving Kamenets

Almost immediately my grandfather left the army he also left Kamenets. By all accounts it was a difficult decision to leave but, because of political activities, the local police had warned my great uncle (Aharon Reichman) that he was at risk of arrest by the Tzar’s secret police and that he and his immediate family would be deported to Siberia.

Mordecai-Moshe Avrimovitch Leiferman’s army

discharge certificate issued 31 August 1899

M. M. and Golda Leiferman with

their children - 1913