|

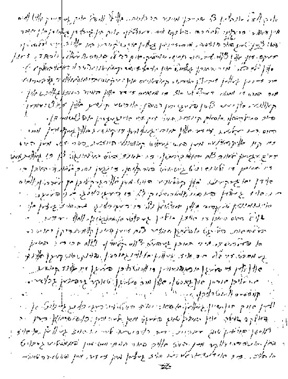

THE MEMOIRS OF ROKHEL LUBAN

(translated from Yiddish by Chaim Freedman)

© Chaim Freedman

| Rokhel

Luban was born in 1898 in the Jewish agricultural colony called

Trudoliubovka (also known to the Jews as Engels) in the government of

Yekaterinoslav in the southeastern Ukraine.

She was the daughter of DINA and AVROM-HILLEL Namakshtansky and a granddaughter of Rabbi PINKHAS Komisaruk (Komesaroff), the rabbi of the nearby colony Grafskoy. Her great grandparents were amongst the original settlers who came to the region when the colonies were established in 1846. These memoirs were completed a few years before Rokhel Luban passed away in Petah Tikvah, Israel in 1979. They were left with her daughter Clara Berchansky. The translation of the memoirs has been divided into two sections. The first ninety pages of the original Yiddish text covers the period from the earliest years recalled by Rokhel, as well as details of the family history told to her by her mother, and concludes when she left Russia and settled in Canada in 1927. Whilst every effort has been made to retain the style of the original Yiddish text, certain sections have not been translated literally. Rather have some sections been précised to convey the essential details. On the other hand, many important sections have been translated word for word, even at the expense of correct English, so as to convey Rokhel's exact intention. The second section covers pages 90 -198 of the Yiddish text and includes the Canadian and Israeli periods. This section is presented as a summary of the essential events. The translator apologizes for his lack of perseverance in completing the translation but feels that it was essential to preserve the first section for posterity. These memoirs are a unique and fascinating presentation of the life of a remarkable woman. Rokhel Luban vividly relates events which she personally experienced whilst giving the socio-historical setting. Although dealing with experiences which were common to many branches of the family, Rokhel relates mainly to events which she was involved in personally. The memoirs provide valuable material for the family history, supplementing, expanding and correcting information provided in `Our Fathers' Harvest'. It is intended that this presentation of Rokhel Luban's memoirs will serve as an eternal memorial to her martyred husband, father and brothers, who perished in the infamous pogrom of 1918, so movingly related in this memoir.

|

R O K H E L L U B A N - M E M O I R S - P A R T 1 .

Ed. Note(# = Explanations not included in the original text)

____________________________________________________________

| |

This is the place where I was born: 1898, ten days before Chanukah. |

| |

These are the residents of our Kolonya (Trudolubovka) |

|

__________________________________________________________

| I

will write my memoirs, as much as I remember and what my mother of

blessed memory used to tell me.

I was born in 1898, ten days before Chanukah (# Nov 28, 1898). We were eight children to our parents, six sons and two daughters: Khaim, Shmilik, me Rokhel, Pinkhas, Velvel, Yokhved, Zalmen and Leibl. We lived in a Jewish colony (Trudolubovka). There were seventeen colonies in Yekaterinoslav Gubernia (# government). Mother told us that her grandfather and grandmother used to live in Kovno. In those times they used to snatch Jewish children to take them for soldiers. Many children were converted. The great-grandfather and great-grandmother took the children and came with them to the Ukraine. They built government houses for them. They gave them land to work. The land belonged to the government; they weren't allowed to sell it nor were they able to acquire more land. In the Kolonya they chose for an elder one who the regime was interested in. He used to take taxes and send them to the regime. There was a Shule. The Jews built a store where all the householders kept their produce for the next year. There was a Feldsher (# an unqualified medical orderly). We had two shops. Two brothers made soap. There was a vineyard. When there was a grape harvest we children went into the vineyard and we found especially large grapes. When I was very young the authorities built a secular school. Half a day they learnt Russian and half Hebrew. The Russian teacher was a Jew from Andreyevka. They built for him and his family a house. The Jewish teacher was my grandfather, my father's father. The school was in our Kolonya and was built of red brick surrounded by a wall and a gate to be closed. In our Kolonya there was one main street and a small one; we called the small one `The Hintisher Gasse' (#The Dog's Street). One person used to raise dogs and sell them. The Shule stood at the junction of the Hintisher Gasse. There were two shops, both opposite the Shule. Between the shops lived the rabbi and the Feldsher (Kozintsev). I think that father had twelve desyatins of land. How it was divided I don't know. When grandfather had three more sons grandfather himself didn't work the land. He was a teacher in the school; he was a Shokhet and Khazan. In his young days it was hard for my father. He didn't have all the machines one needed to work the land. When my brothers grew up and they knew how, they helped. Then things were a lot easier. We used to sow wheat, corn, oats, beans and sunflower for making oil. We had a very small house. But later we built a bigger house with a big chimney and large windows. In his young days my father was a little gentleman. My dear mother was a great housewife. She cooked, washed, sewed, and crocheted; there was nothing my mother didn't know. In my father's house there was no place to lie down. Mama was busy all the time. She made children's pants and all the clothes so that the children always had new clothes. At harvest time Mama didn't sit with crossed hands but helped with everything and don’t forget that as a housewife she had to feed the chickens and roosters and calves and everything was in order in the house. My dear good mother! When one is young one doesn't understand the value of a mother but when one gets old and when oneself is a mother, only then do you understand how to value it. My mother was from another Kolonya (Grafskoy), seven versts from us. My mother did not have a mother. Grandmother died when she brought my mother into the world. Grandfather was the rabbi of Grafskoy. They were seven children, four sons and three daughters. The eldest son Zalmen was a rabbi, Mendel, Ester, Meir, Simkha, my mother Dina and another sister, from one father but not one mother, Reizel. I don't know why it was, but a rabbi could not remain without a wife. Aunt Reizel's mother had a son from her first husband. The son was not all there. He was older than Uncle Zalmen. When the time came when he was liable for conscription there was a commotion. Why? For the sake of the simpleton Zalmen would have to take his place. They decided to make a provisory divorce. The Aunt Reizel's mother was a dear wife. They indeed took uncle Zalmen to serve. He was there a Feldsher and used to heal the soldiers. He made a kosher kitchen for them. But grandfather himself already no longer lived with his wife. Aunt Reizel did not want to go away from grandfather. Aunt came every day and used to cook for him and do the washing and help with the children. All the grandfather's children belonged to their one family. After his service, Uncle Zalmen married and had three sons and four daughters. The uncle I will never forget. He was a Mentsh and a Neshoma (# good soul). It is not possible to write enough of his goodness. Now I will give the names of my cousins, Uncle Zalmen's children: Khaim-Sholem, Mottel, Khaya-Rokhel, Meir, Luba, and the other two I can't remember. Uncle Zalmen's wife was called Mindel. Uncle Mendel, his wife Beila: the first son Zalmen, Yaakov Leib, Yokhved, Binyomin, Basse, Zlate, Pinkhas, and Velvel. Ester; her husband was called Khaim-Moshe. They had only one son - they had no other children. They died young. For a Segula (# lucky charm) they gave him the name of the Brisker Rov Yosef-Dov. (# Soloveitchik). They dressed him in strange clothes until he was six years old. Uncle Khaim-Moshe was an affluent man. He used to have in Mikhailovka a wholesale business for all sorts of leather.