![]()

Chaim-David’s

Shoemaker Shop

By J. M. [Jacob Meyer] Pukacz

(From the magazine Belchatow

Week [Belchatowski

Tydzien] No. 32/158

Translated into Polish, from the original Yiddish, by Szoszana Raczynska

Translated from the Polish by

Andrzej Selerowicz

[Edited by Jerry Liebowitz]

PART

1

[Daily life of a poor Jewish family in Belchatow]

There

were different and unusual buildings in Belchatow. Not one of them, however, was

similar to Chaim-David’s shoemaker shop in Pabianicka Street, to which you had

to climb up three short steps, leading to a tall, narrow glass door.

This

was not a shoe shop in the modern sense of the word. This was a rather poor

Belchatow abode where his entire belongings were placed together with the

children and working place. Countless articles and packaged goods were squeezed

in between the four dark walls, and remembering and keeping track of them would

have required the memory of a Minister of State. There were no windows in the

narrow, gloomy room. The little bit of sunlight came through the glass door,

although there was almost always somebody standing there, watching pedestrians

walking down the narrow stone sidewalk of the paved Pabianicka Street.

Just

to the right of the entrance stood two seldom made beds one after another. Next

to the first one stood a spinning wheel which was used by the children, Mendel

or Pesha. In a corner of the room across from the second bed was a cast iron

stove on which the modest food, mostly potatoes as in many of Belchatow’s

houses, was cooked.

In

the wintertime a kettle with boiling water always stood there. People took water

and mixed it with a bit of chicory and a piece of hard Polish sugar.

On

the other wall, a small cupboard stood near the kitchen table, and another

larger table, permanently covered with books, notebooks, newspapers, magazines,

shoes, slippers, galoshes, wooden shoe forms, and other paraphernalia. Closer to

the door there was the workbench with a three-legged stool, where shoemaker,

Chaim-David, used to sit, dream, play the philosopher and work. On the other

side, near the door, a bench stood for customers, guests or simply loafers,

where also Szprynce (mother) mostly sat and read out loud a book, newspaper, or

magazine. This kind of close quarters was characteristic for the majority of

Belchatow’s inhabitants.

In

the weaving workshops, for example, two or three looms filled up almost the

entire space of the house so that all other household utensils were incredibly

squeezed together. This lack of space led to some comic episodes. I remember one

of them:

[A comic episode]

The

shoemaker, Chaim-David, was a great fan of noodles. His wife, Szprynce, decided

once to make noodle dough. But she had only a handful of black rye flour, and

no eggs. But where is it written that eggs are necessary to make noodle dough?

So she kneaded the dough using water, rolled it out and put it out to dry on the

bench. In the meantime a neighbor lady, who was a bit near-sighted, came for a

visit, and sat down at the bench where the dough was placed. A few minutes

later, she stood up with the dough sticking to her dress. On that day Chaim-David wasn’t able to enjoy noodles and his noodle dream went up in

smoke.

[Magazines and Newspapers]

The

working day started at eight in the morning, and the evening went on and on,

sometimes until midnight. The first chores to be done in the morning belonged to

Mendel, the son. He went to the post office to fetch newspapers and magazines,

which had been sent to Chaim-David’s address from all over Poland.

Chaim-David

had a special way of getting Jewish and Polish magazines without paying the

subscription costs. Even if he wanted to pay he couldn’t because he did not

have any money. He wrote to various editorial offices as an unemployed person

who despite his condition wanted to read their magazines. And so he received

them free of charge.

In

this way the shoe shop became probably the one and only place in Belchatow which

subscribed to “Gazeta Polska”, “Wiadomosci Literackie”, “Kurier

Poranny”, “Robotnik”, “Folks Cajtung”, “Hajnt”, “Der Frajnd”,

“Literarisze Bleter”, “Literarisze Tribune” and many others which were

printed in Poland in the 30s.

And

when you get a package of newspapers, you should read them! So Chaim-David put

away his hammer, spit the nails out of his mouth, left a shoe on the tripod and

started reading and commenting on happenings described in the newspapers. But

one can not make money for a living by talking and commenting. No amount of

persuasion and arguments would help. Chaim-David read more then he worked, and

there was still no money in sight. Szprynce had a fantastic idea: “Why should

you read and not work? From this day on, I will read to you out loud and you

will work.” And so it was. This lasted for years and brought peace into their

lives and money as well.

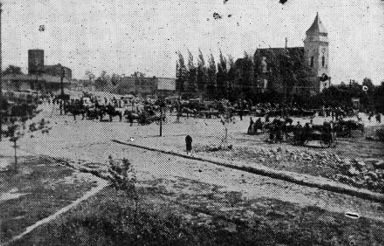

One of Belchatow’s streets, 1930.

[Note:

This same photo is titled "The old market in Belchatow, as it looked in

1930"

in the Belchatow Anniversary Publication of the Mutual Aid

Society of Belchatow

and Its Surrounding Areas (1959), page 11.]

PART 2

[The Cinema]

Chaim-David

Kaufman had another passion – the movies.

There

was one movie theater in Belchatow called “Polonia”. Three times a week:

Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays, movies were shown in two performances.

Every

Friday, without compromise, even if the world would come to an end, Chaim-David,

Szprynce, and their four children went to the movies and watched both films.

Until 1936 only silent movies were shown in Belchatow.

My

friend, Mendel, had a talent to tell stories. He could describe the whole movie,

even particular scenes. In those times, the entire movie art revolved around

Douglas Fairbanks (father), Charlie Chaplin, Valentino, Ramon Novaro, and Greta

Garbo. You will surely ask, how one could afford such an expense like going to

the cinema every week under such a difficult economic situation? Chaim-David

found a solution. Frankly speaking he did not have any money, so he agreed with

the movie theater owner, Janek Rybak, (he was his neighbor, as the movie theater

was also in Pabianicka Street) that he would allow him to enter “on credit”

and the money would be paid back in the form of various shoe repairs and new

soles for the entire Rybak family. Who owed whom money was never a grounds for a

disagreement, and cash was never used to pay off debts. Only by one more movie

performance or the repair of one more pair of worn out shoes. In such poverty -

but what a high spiritual level - four successful children were raised and

educated.

[Political (and religious) tolerance]

One

more characteristic has to be noted of the Kaufman family: The tolerance and

mutual trust towards each other. It was no secret for anybody in Belchatow that

the Kaufmans belonged politically in the left spectrum. They themselves did not

hide this and often told their opinions in discussions about local and general

problems. However when Mendel one day came home and expressed his wish to join

the religious organization “Shomer Hadati” they started to discuss this

topic, but nobody tried to hinder his plan. After a certain time, I saw Mendel

wearing the bright green uniform of “Shomer” and a round cap with a

blue-white brim. Mendel probably remained a student of this school for several

years. He learned Hebrew, went for excursions, and once even got a prize for the

recitation of the part “Motl-Pejsi the Cantor’s Son” during a cultural

evening.

Chaim-David

and Szprynce were extremely happy when Mendel brought home a bar of chocolate

and a bag of candies as a prize for his successful performance.

[Baking matzoth in the new house]

I

left Poland at the end of 1937 and traveled to Argentina. In the first years of

my stay – as every immigrant – I yearned for Chaim-David’s shoe shop and

sent him letters. At the end of 1938 Chaim-David left his flat and moved to the

old house of the Moszkowicz family, also in Pabianicka Street. This new flat was

a part of the inherited house where Szprynces’s sister, Rywa, already lived

with her husband (also a shoemaker) and children, as well as her two brothers,

Peszek and Szlomo-Lejb with their families.

Both

of Szprynce’s brothers, average and peaceful workers, earned their living from

three different types of handwork. In the winter time they were weavers, in the

summer they kept the orchard, and between the holiday of Purim (end of

February/beginning of March) and Easter they baked matzoth. The oven for matzoth

faced the street. Every year they baked matzoth there and had a large group of

regular customers, among the poor people of Pabianicka Street. The process of

baking matzoth was connected to a ritual and started a long time before Purim.

In the room where the oven stood, Rywa and her husband usually lived, and so it

was necessary to find them another place to stay for a period of two months.

Only then began the cleaning, preparation, purifying and kashering of the oven.

The whole Moszkowicz family was involved in the baking of the matzoth. The

hierarchy and standard of work had been set down for years. There were the

persons who mixed the ingredients, and those who kneaded and rolled out the

dough. Mendl and I also had our duties and earned a couple of groschy profit as

well as some kilos of matzoth for Passover, which my mother wrapped in a clean

pillow case and hung it from a hook in the ceiling.

During

the Nazi occupation, Mendel and Jakob Cyngler [Tsingler] hid and cemented the books from

the library in the oven. What destiny became the books after the liquidation of

Jews in Belchatow remained a secret, and nobody has tried to find out what

happened. Probably it will never be clarified.

[Tragic Epilogue]

Life

in the new flat did not last long. Here we approach the end of the memories of

the epilogue of the Jews in Eastern Europe. In September 1939 Hitler invaded

Poland. On the third day of the war, Belchatow was occupied by Nazis, and that

was the beginning of the end.

Chaim-David

was one of the first victims of the Nazi occupation. Together with a group of

other Jews from Belchatow, he was deported to a work camp in Poznan where he

perished.

Belchatow before the war – view of the Old Market (today: Narutowicza Square).

J. M.

Pukacz

Translation from Yiddish by Szoszana Raczynska

[Permission to translate and reprint this

article was granted by the author, who has lived in Argentina since 1937.]