Religion

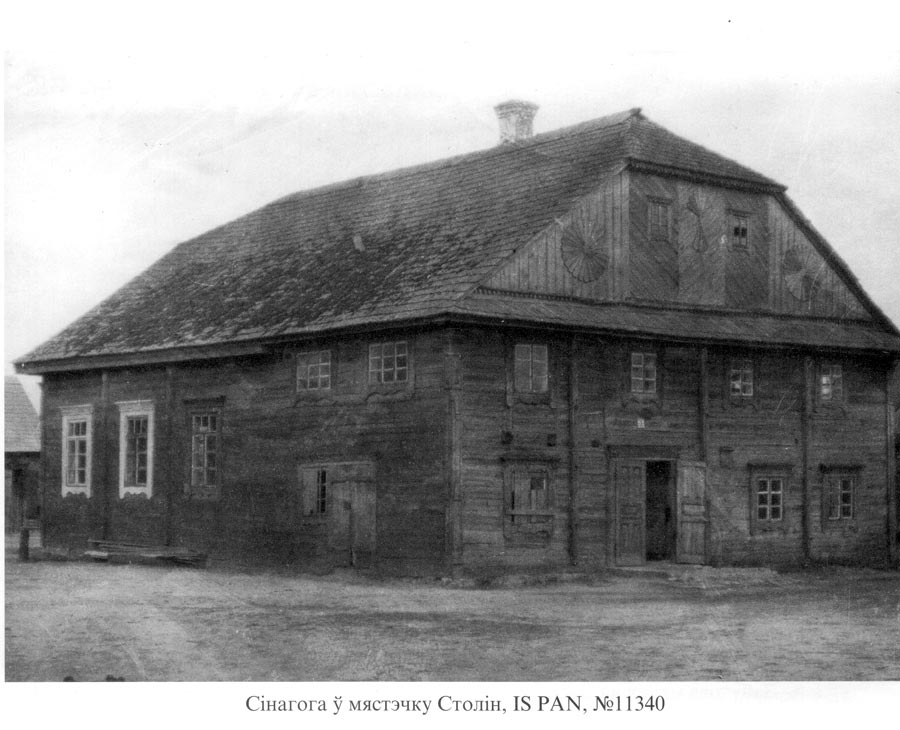

Everything was new and different: sidewalks made of boards, masonry buildings, a marketplace, fairs, and three synagogues on one square! There was a study house, a communal synagogue, and the rebbe’s synagogue. And all the synagogues were conducted in the Sephardic style, like in Duboy. Read more from My Future is in America: Autobiographies of Eastern European Jewish Immigrants »

Karlin-Stolin Chasidim

Rabbi Aharon the Great of Karlin (1736-1772), the founder of the Karlin-Stolin Chassidic dynasty was a disciple of the Maggid of Mezeritch, successor to Rabbi Yisrael Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Chassidism. His grandson, Rabbi Aharon Perlov of Karlin (1802-1872), moved the center of the dynasty to Stolin following an altercation with a rich family of Mitnagdim in Karlin. Aharon II was also the author of the Sefer Beit Aharon, a great work of commentary on Torah, festivals and ethical teachings.

Chasidism in Pinsk and Karlin from Pinsk yizkor book

In 1870, when Rabbi Yisrael Perlov [1870-1921], the future Rebbe of Stolin-Karlin, was born, his grandfather, Rabbi Aharon, was the Rebbe, and his father, Rabbi Asher, was a young man with the promise of a bright future. When the infant Yisrael was only 3 years old, his grandfather and then his father died. Thousands of Stolin-Karlin Chassidim were orphaned of their leaders. It seemed as if an end had come to the Chassidic dynasty that had begun with Rabbi Aharon of Karlin, one of the illustrious disciples of the Maggid of Mezeritch. The senior Chassidim then made a risky decision—they accepted the 3-year-old Yisrael as their leader. Not surprisingly, he was called the “Yenuka” (Child), a name that remained with him all his life. Although he played like other children, he was different. He studied intensely and even then gained respect for his sage advice. The great Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan Spektor once visited Stolin and, after spending two hours with the 12-year-old Yenuka, described him as a gaon. When he was 52 years old, he traveled to Frankfurt for medical treatment and it was there that he died. He had left a will in which he stated that there should be no eulogies at his funeral and that he should be buried in the city where he died. Thus it was that he was buried in Frankfurt, and the Stolin-Karlin Chassidim refer to him as ‘the Frankfurter.’ 1

1 Rabbi Nachman Zakon, The Jewish Experience: 2,000 Years, A Collection of Significant Events, Brooklyn, New York: Shaar Press, 2002