This KehilaLinks page

was created by Phyllis Kramer. Copyright © 2000. Since January 2003

you are visitor#:

This KehilaLinks page

was created by Phyllis Kramer. Copyright © 2000. Since January 2003

you are visitor#: March 15, 1998

Arrival in Hotel " Zalesie" (Behind-the-Wood) in Iwonicz-Zdrój.

Winter is back.

March 16, 1998

Zmigród - Garden of the Snake or Stronghold of the Flying Dragon. At least the coat of arms shows a dragon with bat wings. A town, that lost its charter. Always in the line of fire - in both World Wars. Burnt down and rebuilt, destroyed and still recovering. A village. Today Nowy Zmigród. And Zmigród Stary is now Stary Zmigród. What's in a name. Political hocus-pocus.

Nowy Zmigród. All the Jewish vital records were to be held by the USC of Zmigród, located in the town hall, a typical socialistic concrete monster. Urzad Stanu Cywilnego, a small room with a desk and a copy-machine (hurrah...). The kierownik (head) of the USC, is a tall man in his fifties with dark hair and glasses. And he did something incredible! Without having a computer, he indexed all the Jewish records of Zmigród. His alphabetical register reveals the master; it's a precision work. And he is very pleased with my compliments. "But don't get your hopes up too soon, " he says. "Three weeks ago I had to turn over the pre-1897 birth records to the archive of Skolyszyn." Bad luck. The index however, includes the pre-1897 records, so the lion's share of the research can be done at the USC.

I ask the Director about Zmigród. "Well, I'm a newcomer, as they say here. I am from Jedlicze (or was it Gorlice?). I married into Zmigród. But if you want to know more about the Jewish history, you should ask Mr. S. of the tartak (sawmill) or Mr. B. of the barber shop. They grew up here and went to school together with Jewish children."

After having researched the index and written down all the names that could be of interest, my assistant and I go to the library, looking for a "city map", literature on and old photographs of Zmigród. Nothing. Only a boring book about the region, written in the sixties. The print is so bad that the pictures and the tiny map are useless.

We go to the market, dying for a coffee. We ask several people if there is a café or restaurant in town. The kawiarnia "Kasia" we are referred to, obviously didn't pay off it's a store now, offering plastic flowers, panties, neckties and exercise books. A gray-haired woman, who must have been watching us, comes up to us and asks curiously: "What are you two beautiful ladies looking for? Can I help you?" Smiling she shows us her mouth full of holes and black teeth.

"A café? Over there, at the corner of the market. But it's not

a nice place." She didn't

exaggerate. Entering the establishment, we feel like we're

stepping out of a time machine that

brought us back to the early 1970s. A long dark room with three

rows of small square tables with

cloths that must have been white in the sixties. The brown

covers of the seats and backs of the

rickety metal chairs are threadbare. But we don't turn back. Our

desire for coffee is too great, and

I want to experience this "komuna", the communistic society I

was spared. We cut our way

through the smoke of "Popularna" cigarettes. Of course we are

being scrutinized from head

to toe. Behind the bar (think of the 1930s!) a still not

completely worn out woman. She is

astonished and happy to see species of her own gender. Coffee???

(Nobody has ever ordered coffee

there...) But she has hot water, so it's no problem to serve

Turkish coffee in a glass - a habit that

still has tradition not only in Zmigród. Sitting at one of the

tables at the wall, we try to make out

the other guests. Farmers, laborers, unemployed. Playing cards,

talking, using the same poor

vocabulary like in the back streets of Warsaw. And they are all

drinking the same. No, not vodka,

that's too expensive. On every table stands a bottle of

strawberry wine, the kind that makes your

head explode after one sip. And the bottle has to be emptied,

even if you're already drunk, blind

or dead. But the coffee was good!

It's time to pay a visit to Mr. Wieslaw S. He lives next to the tartak at the south end of town, on the road to Katy (pron. Konty). Again this time machine feeling. We are now entering the world of the 1930s. An old damaged sawmill, piles of tree trunks in the big yard. A wonderful smell. And next to the tartak a beautiful wooden house that shows the welfare of the past. At our knocking, the door is opened and a long-haired German shepherd jumps down the few steps. He seems to say: "Hi, I'm the so-called watch dog, but if you don't bite my boss, I would love to chat and play with you".

We would never bite his boss. Mr. S. is a small, delicate but lively, man in his seventies, who invites us into his house without bothering about our dirty boots. He is well-read, intelligent, open-minded and charming, charming, charming. He heats up the stove and excuses himself for not having vacuumed. "As mother was still alive, it was always clean. Now I have to cope with Miszek's fur. Four years ago he walked into me and stayed." Miszek adores Wieslaw, he follows him wherever he goes.

We are sitting at the big table in the middle of the sparsely furnished room and Wieslaw rummages in cupboards and drawers, fishing out photos, negatives, publications. "I would enlarge the photos myself, but I have no time." I am flabbergasted at his comment. Mr. S. was born in the 1920s, in the Tarnopol area (today's Ukraine). His father was from Toki, a stone's throw away from Zmigród, but he left at the beginning of W.W.I, looking for work. In 1928 his father came back to Zmigród, bought the sawmill, put things in order, and, in 1932 Wiesio and his mother joined him. Wiesio went to school together with Jewish children. "In those times we were all one melting pot. Who made a point out of it, if you were Greek-Orthodox, Jewish, Catholic or Protestant? Every group had its own place of worship, its own holidays, its own habits and traditions. And its own businesses. I still remember the taste of these delicious cakes I used to buy at the Jewish baker's shop. I love sweets."

It was a flourishing town. The market was the place where

Geschäfte were made. Always

crowded. But on Friday evenings the stalls and shops were

closed, and the Jews vanished in their

homes, preparing shabbes.

On Saturdays in black-dressed men with fur hats rushed to the

synagogue. "The Old Synagogue was used for normal prayers, the

New one for Sabbath

and special occasions. And behind them was the chejder, in a

wooden house."

"There were two synagogues?"

"Yes, next to each other. And to the right of the Old one was

Eisenberg's shop, you see?"

Wieslaw shows some pictures. Amazing.

The New Synagogue already existed in 1910.

This 1930 postcard shows the east side of the market

place with Berger's house.

The shuls stood off the market at today's Karcinski street, the main north-south road. On the same side, but at the market, stood the typical houses with arches. One of them belonged to the Bergers.

Opposite, at the NW corner of the market is the church. Next to the church at the west side two of the few Jewish houses with shops that have remained. In the remarkable house at the same corner of the church was Buchsenbaum's restaurant.

Wiesio continues: "During the war we had to move away. The battles were too heavy. The Germans built bunkers, shelters under our garden. In 1945 we came back. My father wanted to go to America, but my mother said that if the house is still standing, we'll stay. The house was there, without windows. The mill was taken apart, the machines were brought to Germany. We started to build up the tartak. In 1946 the nationalization laws were passed. But private enterprises were still allowed. We should have listened to Ivan 'the Kozak', who fled from the Soviet-Union. He tried to convince us that the communists take everything, even the smallest private business. In 1953 the sawmill was nationalized. And this situation hasn't changed till today."

March 17, 1998

The Director of the USC gives me the newly bound vital record books.

While I am studying your families, a huge man with a short cut mustache drops into the USC. The Kierownik introduces him: "This is the man I told you about yesterday, Mr. B.". He is dressed like a hunter, his rifle is his mouth. "Are you Jewish? (Only goyim ask that) No? Well, as a matter of fact I'm bored with that Jewish history of Zmigród. And to tell you the truth - I always say what I feel - nie lubie Zydków, I don't like Jews (he uses the diminuitive of Zydów, which is very insulting). Many, many times I talked to them, I helped them, I even sent them pictures; Jews from the States, from Belgium, but you know what?- None of them ever thanked me for my services. I'm not interested in Dollars, shall they keep them in their pockets. A word of honor, a word of thanks would do. I have done many good things in my life, but I don't praise myself for that. But the Jews have to put their names everywhere. Na Halbówie, on the Halbów, they carve their names in golden letters on signs and plates, showing that they financed the monument. I am far from interested in Dollars. But people should learn to say: thank you. Not the Germans created the ghettos, the Jews themselves did, they isolated themselves, and didn't allow Poles on their territory, they bought houses and property, and kept together. Even if they didn't build a house themselves on a plot, they never allowed a Pole to do so. They weren't rich, they were laborers, craftsmen, maybe one or two were farmers, who had a piece of land. They weren't that honorable, they stole from each other, they denounced each other, the Jewish police worked together with the Nazis, they put the bullets into the guns of the Germans, they betrayed their own people. And at the cemetery only one grave, of that one Jew, that died in 1947, after the war."I thank him for his exposition, and B. leaves.

The cemetery is located in the northern part of town. Good, that Wiesio had explained, where to find it, otherwise I would have passed it. It's in the wood along the road that leads to Toki and Jaslo. And there is wood, because there is a grave-yard. Trees have pierced their roots through stone. The few mazzevahs, that are not too damaged, are small and thin. The engraved symbols are simple: a krojn, a hirsch, a sejfer.

Again we drop into Mr. S. He borrows us two negatives, some photos and a booklet about Jaslo. Then we drive to Jaslo, to a photographer who will make us reproductions and b/w prints.

March 18, 1998

In the morning we meet the Kierownik of the USC to order copies

of the records. Then we drive to Skolyszyn to the archive. The

Polish archives are usually located in historical buildings. The

one in Skolyszyn as well, but we have to search for it, because

we don't expect such a young history: it houses in the offices

of a former kolkhoz, a collective farm. And I bet, a lot of work

had to be done to suit the horrible building to its new

purposes. The first soul we meet on the second floor, is a woman

dressed in a smock with flower pattern, sitting at a desk piled

up with books. She wears thick glasses and is reading; the book

almost touches her nose.

"Yes?"

In a friendly voice, a little bit joking I say: "Dzien dobry,

what an odd place for an archive".

"That's not my fault", she barks.

This woman hasn't escaped from the "komuna" yet, and she

probably never will.

"Ask pani kierownik for records", and she points with her head

to the wall. The director is a lot friendlier. After having

checked my papers, she says:

"I received the Zmigród records three weeks ago. I don't know

exactly in what state they are, but there is an index". The

index she shows me is a copy of the booklet in Zmigród, bound by

the Kierownik of the USC himself. That man is really amazing.

I hope I haven't lost you by now. I won't torture you by describing the rest of the week. Just one thing more: Dukla must have been one of the most beautiful townlets of Galicia. And visiting Rymanów, that was built on top of a mountain, is a must.

Following our three night stay in Warsaw, Poland, our tour of 14 couples and two single women moved on by bus to the city of Cracow (Krakau in German), the capital of the province of Galicia. This area of Poland had been part of the Hapsburg Austrio-Hungary Empire until the end of WW I and then was separated during the break-up of the Empire and returned to Poland in late 1917. Twenty-one years later it was the first province of Poland to be attacked by the Germans at the start of WW II in 1939. Whereas Warsaw (the new capital of Poland) was 85 % destroyed by German bombing and cannonade, Cracow (the old Capital of Polish Kings), because it had once been part of the Austrian Hapsburg Empire, was fundamentally untouched.

The first full day of Cracow we visited the Palaces of the

Polish Kings, the Jewish Quarter (a very large portion of the

city) and the old city. Since we were scheduled to visit a

Polish salt mine and then peruse the city on our own in the

afternoon, we hired a private guide-driver to take us to

Zmigrod. He was a strapping young man about 30, college

educated, who picked us up  at our hotel at 8 AM and took us across the Polish countryside,

mostly on back roads, to the Shtetl of Zmigrod, now known as

Nowy (New) Zmigrod. It is a small village in the foothills of

the Carpathian Mountains quite close to the Slovenia border, and

not far from Hungary, Rumania, and the Ukraine in the southeast

corner of Poland. After a 4 hour drive through these rolling

hills we finally arrived in Zmigrod,

at our hotel at 8 AM and took us across the Polish countryside,

mostly on back roads, to the Shtetl of Zmigrod, now known as

Nowy (New) Zmigrod. It is a small village in the foothills of

the Carpathian Mountains quite close to the Slovenia border, and

not far from Hungary, Rumania, and the Ukraine in the southeast

corner of Poland. After a 4 hour drive through these rolling

hills we finally arrived in Zmigrod,  a quaint little village not much different than I have seen in

middle and southeastern Pennsylvania or upper New York State.

The population total hasn't changed much at all----but there are

no Jews living in town or within 75 miles of the town. They are

all gone.

a quaint little village not much different than I have seen in

middle and southeastern Pennsylvania or upper New York State.

The population total hasn't changed much at all----but there are

no Jews living in town or within 75 miles of the town. They are

all gone.

From the outskirts we drove straight to our first stop---City

Hall---in the hope that they would be able to show me the house

location of where my Grandfather and his family lived. It was  a funny experience because we arrived at about 11:30 AM and the

door to the office of records was locked. It turned out that the

young woman who ran the statistics office was busy breast

feeding her baby. Suddenly the door opened and her husb whisked

the baby away. Through my guide-translator I think I made my

request for information clear but her reply was that there were

no Jews living in Zmigrod and the records of their births and

deaths were no longer kept in the City Hall but were held in the

provincial capital of Cracow. However, since I knew that

building 45 in town was on the square and she showed the guide

where it was. She also informed him how to get to the site of

the mass slaughter of all Jews in Zmigrod and surrounding

villages in July, 1942 and also where the ancient Jewish

Cemetery was.

a funny experience because we arrived at about 11:30 AM and the

door to the office of records was locked. It turned out that the

young woman who ran the statistics office was busy breast

feeding her baby. Suddenly the door opened and her husb whisked

the baby away. Through my guide-translator I think I made my

request for information clear but her reply was that there were

no Jews living in Zmigrod and the records of their births and

deaths were no longer kept in the City Hall but were held in the

provincial capital of Cracow. However, since I knew that

building 45 in town was on the square and she showed the guide

where it was. She also informed him how to get to the site of

the mass slaughter of all Jews in Zmigrod and surrounding

villages in July, 1942 and also where the ancient Jewish

Cemetery was.

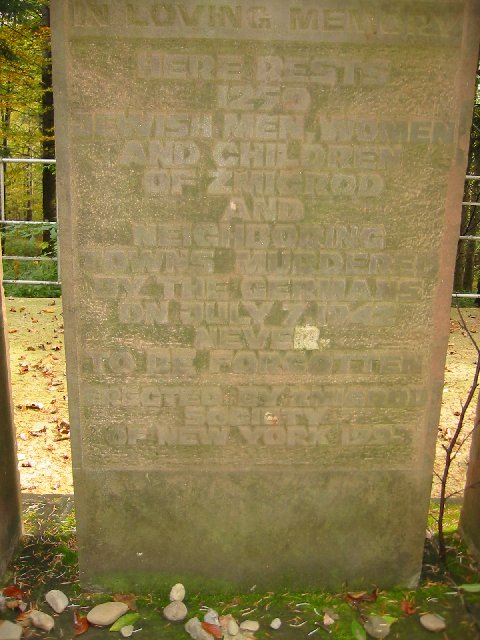

Although disappointed in not being able to find any official

records of births, deaths, and marriages, we proceeded out of

town on a paved two lane road about 1-2 miles and almost missed

the marker we were looking for. Our guide backed up and pulled

off the road and there was a marker, not particularly obvious to

passersby.

Although I do not understand (or even can pronounce) Polish,

this sign, as translated by our guide says "Here marks the

place where 1250 Jews were slaughtered on June 7, 1942 by

barbarian Hitler henchmen. If there was a more peaceful

setting than here in Poland, I did not find it.

It was warm and sunny, although shady in the woods, fresh

smelling, birds chirping. I just tried to imagine what is was

like on June 7, 1942 when all these people were ordered  to strip, babies were screaming, mothers were screaming, old men

were shoved and pushed along after being trucked up the hill.

Everyone could see and hear what was happening. It is better

described in the history of Zmigrod which I sent to many of you.

I will gladly send more---just write and asked. There was an

eye-witness who survived in the woods.

to strip, babies were screaming, mothers were screaming, old men

were shoved and pushed along after being trucked up the hill.

Everyone could see and hear what was happening. It is better

described in the history of Zmigrod which I sent to many of you.

I will gladly send more---just write and asked. There was an

eye-witness who survived in the woods.

Ann and I stopped to have our guide take our pictures before

we actually saw the site of the slaughter.

We continued to walk another 100 yards into the woods and came

upon a large slab of concrete, covered with leaves on which were

several grave markers, surrounded by a low wrought iron fence.  This was the place where in one day 1250 members of the Zmigrod

Jewish community were annihilated ---one bullet in the back of

the neck and pushed into a deep pit. Babies weren't shot---just

tossed in and soon covered by bodies.

This was the place where in one day 1250 members of the Zmigrod

Jewish community were annihilated ---one bullet in the back of

the neck and pushed into a deep pit. Babies weren't shot---just

tossed in and soon covered by bodies.

I found it very hard to walk away from this place. I stared at all the individual burial stones trying to read them. Some in Hebrew, some in Polish, some in Yiddish and some in English. 1250 men, women and children. Up close and personal and not like the assembly lines of the following years in Auschwitz, Birkinau, and elsewhere. It is beyond my capacity to understand how men can do this and ever sleep peacefully again.

Many of the memorial stones were placed years later when the

place of mass murder was discovered. Here are all of the stones.

I just couldn't quit.

We finally left the cemetery with a feeling that we had

accomplished something. It was like coming to Elizabeth, NJ and

spending a few moments at the gravesites of our parents. I

suppose you need a good imagination to feel like this was

family, as our family has been in the USA for well over 100

years, but I remember my dad getting so terribly upset when news

of what happened to the Jews of Galicia in Auschwitz and

Birkinau and in separate little Shtetls like Zmigrod before the

mechanization of murder came into being. I don't think he really

knew any of the Galician cousins, but it is still a fascinating

tragedy to think of all the new discoveries thant might have

been made by all those wonderful brains that our people seem to

turn out year after year. One million youngsters and babies

never had a chance to find cures for cancer, heart disease,

pollution, earth-warming and so many other things.

Our next stop was again one we almost missed. We drove back

thru town and onto another country road and pulled into a

farmyard about a mile out of town. The guide spoke in Polish to

the farmer who said we missed the driveway by just a few  yards, and then we were driving on gravel and no road at all

and came to the ancient Zmigrod Jewish Cemetery. Since

there were no Jews in this area for over 60 years, one would

hardly expect to see a replica of home cemeteries, but even so,

look at this.

yards, and then we were driving on gravel and no road at all

and came to the ancient Zmigrod Jewish Cemetery. Since

there were no Jews in this area for over 60 years, one would

hardly expect to see a replica of home cemeteries, but even so,

look at this.

As the day wore on there was one final thing I wanted to look

at and we drove into the  center of town, a typical town square with a park in the center

and 4 streets surrounding it.

center of town, a typical town square with a park in the center

and 4 streets surrounding it.

On the West side of the square was the beginning of the "Jewish

Section" of town. There was a  row of stores there---not from 1880 when my Grandpa left, but

newly built buildings probably dating to after WW II. The old

wooden synagogue remains only in pictures now, and I do have

some of them. It was once a small village with a very prominent

Hasidic Rabbi. I can give you more history. I did find one

building that the guide thought predated WW II and it is

photographed.

row of stores there---not from 1880 when my Grandpa left, but

newly built buildings probably dating to after WW II. The old

wooden synagogue remains only in pictures now, and I do have

some of them. It was once a small village with a very prominent

Hasidic Rabbi. I can give you more history. I did find one

building that the guide thought predated WW II and it is

photographed.

The trip home seemed quicker although it truly wasn't, but we were caught in a lot of commuter traffic when we got near Cracow. It was an expensive day and a long day, but I will always remember it. I wouldn't do it again but I do not regret going there once. My whole attitude about Poland has changed. I know there are still some crazy antisemitic Poles, but I came to realize that their choices were not much better than the Jews of Poland. Assisting a Jew in any way was punishable by death of the entire family. How many would take that risk?? And the treatment of Polish people was just a few degrees better than the treatment of Polish Jews. There is no excuse for what happened in Polish concentration camps and yet here we are---60 some odd years later, watching it happen in Darfur, fearing that it will happen again in Israel. Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. I hope the world has learned.

Dr. Howard Haskel Lehr, September 2007

Return to Table of Contents