HALPERN AND FELLMANN–Escape from the Nazis and Life Afterwards

Dr. Ilan Fellmann's translation of his essays, originally in German, published in DAVID, Nr. 86/87 of September/October 2010

PART ONE

I must concede that the literature about Shoah and the escape of hundreds of thousand of Jews from central Europe is described in more than enough books. As my daughter gave me the book “Schuhhaus Pallas” (“Shoe Shop Pallas”) written by German journalist Amelie Fried that describes the history of her Jewish (but baptized) father in the Third Reich, I felt spontaneously – I will enrich the literature with the variant account of my families—the Halperns and the Fellmanns.

“Who shall read this?” asked my eighty-five-year old mother, and I answered: “Mama, don’t worry, it will be very thrilling.” I can explain to you why. There are only a few biographies about total families who became Shoah victims and include a limited history in their consideration. I studied the history of the First Republic (in Austria), the Weimar Republic (in Germany) and Palestine (from 1930-1948) and tried to develop this in a brief way before the spectator’s eyes. I place my relatives as acting figures in this pertinent history, and hope – you’ll find a dynamic picture about this cruel time and the humans, who had to live in it. In the heart of the story you will find my grandparents: Max Fellmann (born 1883 in Zurawno, south of Lwów, died 1965 in Haifa) and Adele (Fellmann, born Harmel in 1896 in Vienna, died 1969 in Haifa) and my maternal grand parents Michael Halpern (born 1889 in Pawczow near Tschernowitz, died 1950 in Vienna) and Dora Halpern (born Tausend in 1896 in Vienna, died in 1984 in Vienna), and my parents: Fritz Shlomo Fellmann (born in Vienna in 1918, died in Haifa in 1991) and Trude Fellmann (born Halpern in 1925 in Baden near Vienna, lives in Vienna). A completely normal story? Yes and no, I leave it for you to decide.

My grandpa Max already realized in 1933 that there will be no further life for Jews in Austria, since Hitler was appointed to Reichskanzler on January 30, 1933 in Berlin. Max was well versed in migration matters as a fourteen-year-old boy because of his adventurous journey from the Shtetl Zurawno, 80 km south of Lemberg (Lwòw, now Ukraine) to Vienna to try his luck. He arrived with just his clothes on his body. Hard years full of pain followed. He first worked as an unpaid sales aid (chapper) in a clothes shop in the city and later as salesmen, and, from 1910, as a businessman with his own shop on Südtirolerplatz in the tenth Vienna suburb. He had luck—his business principles made him very successful. When he married his wife Adele Harmel—the daughter of the Levite Moses Aron Harmel—he already wore a tailcoat and top hat and elegant dress shirt and white leather gloves. My grandma wore an elegant white silk wedding dress, white bridal veil and modern white stack-heel shoes. I got the photo of this wedding ceremony from my second cousin Hilda Rubin Pierce who lived in San Diego in the middle 1990s.

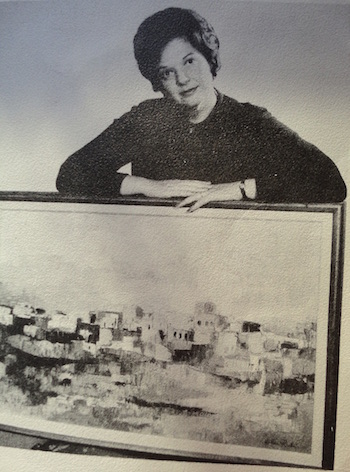

Hilda Pierce, born Harmel, grew up together with my father and a third cousin, Benno (Benjamin) Bordiga, in Weyringer Hof in the Weyringergasse 38 in the upper middle class 4th Vienna suburb. Hilda fled via London to the US in 1939 and became a famous painter in Chicago. Benno came via Bristol in 1940 to NYC and became a successful manufacturer of car parts, but also a paintings collector, e.g. Henry Toulouse-Lautrec, but also Schiele, Klimt, Lionel Feininger and other painters, and he became a patron of the Metropolitan Opera. His self founded company Allomatic Industries, producer of mechanical automobile parts, was sold at the end of the 20th century.

Max, not originally a burning first-hand Zionist, wanted under all circumstances to emigrate to Palestine - to Haifa, a city which Theodor Herzl found beautiful and in which Max wanted to be buried one day. Said -- done. Already in the fall of 1933, he travelled to Haifa, bought land on the hills of the Carmel and built his house. For more than eight months he stood daily on the building site, watched every sack of cement and all working activities. But he bought the building site for too much money from an Arab, and the constructor also cheated him. Regardless, at the end there stood a beautiful apartment building with a view to the bay and harbour of Haifa. The Balabuss took the best apartment under the roof, with three living rooms and two balconies; the other apartments were rented. In July 1934, Max fetched his wife Adele and his son Fritz, who just finished the fifth grade of high school in Rainer-Gymnasium, to Haifa. Both came more or less unwillingly, because they liked the Vienna music, Opera and Burgtheater – not so much desert and heat.

My maternal grandparents thought a lot of the time that nothing will be eaten as hot as cooked. They would overcome the Austro-Fascism with Dollfuss and his successor Schuschnigg—a deceptive misjudgement, the incidents later showed. Hitler crossed the ways of the parents of my grandmother or other relatives in his Viennese time, when he tried – mostly without success – to sell his drawings to wealthy Jews. From this he seems to have gone over board with his racist prejudices against Jews.

Michael Halpern wished to stay in Vienna. Maybe he was influenced by his economical situation; he has lost a lot of his fortune in the world economic crisis in the 1930s, had to sell three of his four houses including his villa in Perchtoldsdorf (elegant village near Vienna) and the business was running bad. He was close to bankruptcy proceedings but paid little by little all his debts. He was a man of honour.

Der Anschluss of Austria on March 12, 1938 found him on the wrong foot. On the last day before he fled on 11 March with his second oldest son Robert to Pressburg (Bratislava) by railway and little later to Italy. We all do not know what he did there. I thought for a long time he would have visited his older brother Adolph in Genova, but he never appeared there; maybe he was in Milano and studied business opportunities. The oldest son Ernst/Aron did not accompany them, because he wished to remain with his girl friend Susi Steinbock, his great love, in Vienna. The only daughter Trude was not taken with them because they thought she was not very endangered. Six weeks later Michael and Robert returned to Vienna, because of misinterpretation of the political situation.

Already on the railway station, filled with SA personnel on the platforms, Michael saw his error. A former client, now SA officer, recognized Michael Halpern and shouted: “Are you crazy, Mr. Halpern, what are you doing here? Try to make your exit. If someone recognizes you, you are lost”. Michael looked to come home rapidly. The way to his house was not far. Dora, his wife, awaited him already. She was glad to have her husband and son back again.

Shortly after this, Michael heard from the SA man that the railway stations generally stood under strict observation. Wealthy or disliked persons were caught and brought often enough to KZ Dachau. At the moment this SA man saved Michael from the worst through his silence. Nobody could imagine what else could follow. A salesman, who lived in the house and was working for a German steel company, Mr. Zwirn, was arrested by the Gestapo and set free some days later. My grandma saw him, obviously hurt, and how hard he was dragging himself in the staircase on the way to his apartment. In spite of the attempts of the physician Dr. Viktor Ullmann, who lived in this house and tried to save him, he died shortly after the sustained tortures.

Life for Jews became worse and worse. At least after the pogrom on Reichskristallnacht of 9.-10. November 1938, which ware especially cruel in Vienna, it was clear for Jews: we all have to flee, very fast. One moment! The term “Reichskristallnacht” was used in a mocking way by the Nazis. The correct name for it was November pogrom 1938. It was ordered and organized by Nazi authorities and in no way a spontaneous uprising as maintained by the propaganda. Previously, there were a lot of activities against Jews, which culminated in the demolition of Jewish synagogues in June 1938 in Munich and Nuremberg, and in Dortmund in September. In the night from 9th to 10th November, 400 Jews were killed and a big number seriously hurt; 1.400 synagogues and praying rooms and other Jewish official places were destroyed, and thousands of Jewish shops, flats and also cemeteries damaged. On November 10, 1938, 30.000 Jews were arrested in the KZ Dachau, Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen. Some hundred Jews ware murdered.

Michael, Dora and my thirteen-year-old mother Trude fled late, but not too late on November 16, 1938, six days after the Reichskristallnacht, with some difficulties – and at this time, illegally – over the western border of Germany via Karlsruhe, Freiburg and Lörrach on November 20, 1938 to Basel in Switzerland and then soon after to Muhlhouse (France). They were lead as pedestrians over the well-guarded German-Swiss border by a paid Swiss escape agent, Frieda. And they continued on foot from Basel to the French border, a pathway of some hours. They totally feared the Swiss border police, because it often sent back Jewish fugitives to the German Reich. Michael, who suffered from heart problems, wanted to sit down often, to have more breaks and was near to giving up. “Papa, we have to go on!” urged Trude and saved Michael’s life. On the other side of the border waited a reserved car, which brought them to Muhlhouse from where they travelled by train to Paris.

The entering of the Altreich (German Reich without Austria) was strictly forbidden for Jews as mentioned above. I did not know why my family took this high risk. By and by, I understood that one of the possible escape routes went through Basel, and the financier of the escape, Olga Krupnik, possessed these contacts. Several days into the escape in Germany, the family never slept in hotels, but in trains, flats of relatives or waited in railway restaurants. This was because of the strict supervision of all these institutions, which were not harmless. Grandma Dora told me she did not feel like she was really in danger because of their European non-Jewish appearance and modern clothes.

Living for many years in Paris was Hilda Weizenbaum, born Drucker, the daughter of one of the sisters of Dora and Olga, Antonia Drucker (“Tante Toni”). Hilda was married to Leon (“Leo”) Weizenbaum (later in USA: White), a shop owner and furrier, who made a lot of money and could support his impoverished relatives. Their elegant, well-equipped apartment was situated close to Rue Faubourg-Bergére and the cabaret Folies Bergéres. After some days, the Halperns had to move to a cheap hotel nearby, a no-tell hotel. It seems that there were some differences. At this time many refugees already lived in Paris.

As my mother, a teenager, could not attend to school, she walked through Paris, sat in parks and quickly learned basic French. She especially liked the photos of beautiful dancers and cabaret stars in the shop windows of Folies-Bergéres.

Hilda’s brothers Ernst and Kurt Drucker, twins, came to Paris as well and were, after a while, supported by Leo, who bought ship tickets to Cuba for them. My mother remembered decades later that there were discussions between Hilda and Leo about this. Hilda’s family was big and Leo’s money reserves not unlimited. At the end, Hilda carried her point, and she and my mother accompanied the twins to the railway station where the trains to southern France departed. This was the start of their journey to Havana.

A sister of Michael and aunt of my mother, Hilda Hoffmann, born Halpern, lived with her husband and their three sons in the former apartment of her father and family patriarch Joseph Mayer in Seitenstettengasse 4 in Vienna (facing the historic town temple and office of Israelite Community Office (Israelitische Kultusgemeinde). She could not depart. Her grand nephew, Chanan Tell, explained to me in Tel Aviv on April 2, 2010, that “Tante Hilda did not wish to leave Vienna, although everything told her she should disappear”.

“Wanted or could not flee?” I had too little information. Don’t forget, if you wanted to emigrate, you needed a valid passport of the German Reich, which was only issued after paying all demanded taxes including Reichsfluchtsteuer. This tax could easily cost for five people some thousand Reichsmark, a high amount. The Hoffmann family was not wealthy and it was a hard time without jobs and income. Maybe was Hilda Hoffmann too proud to ask one of the rich relatives, like her brothers in law Joseph and Adolph Katz, wealthy businessmen or Olga Krupnik, her sister in law for some money. But Olga for example supported already a lot of relatives—and the family was big. Maybe she was not asked. The history showed that staying in Vienna was the wrong choice—it lead in 1942 directly to KZ Theresienstadt and in 1944 to KZ Auschwitz, where Hilda and two of her sons were suddenly gassed; only her son Bert and his father survived. (I found Burt in 2012 in Willmington, NC. He died in Feb. 2015).

Another brother of Michael, Adolph Mayer, his oldest sibling, emigrated with his family in the late 1930s from Vienna to Genova, where he felt safe and had a good life. When the Italians enacted the racist law (similar to Nurenberg race law) that excluded Jews from social and economic life they fled to southern France. Unfortunately, the Vichy government interned Adolph and his eighteen-year-old son Kurt in Les Milles, Gurs and Rivesaltes. Both were transported via Drancy to Auschwitz in 1942 and killed. The children’s mother and the only daughter, Edith Mayer (married Cord), survived in the underground and immigrated after WWII to the US (Maryland).

In the year 1938, the possibilities to emigrate were very restricted for Jews, because hardly a state in Central Europe or elsewhere (e.g. US) was still willing to accept immigrations of foreign Jews who were legally German citizens. This happened in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Italy, Switzerland, and other states. So what to do?

Good advice was also hard to find for the normally smart Jews with life experience. The only thing that could help – well guessed! – was money that could be changed directly for life and intactness. As I wrote above the emigration of German Reich was only possible with a passport (including the red letter “J” for Jew), which was fundamental for foreign visas and getting an affidavit (official declaration of a citizen to take over the costs for the new immigrant). Without this document it was impossible to travel to United States. As you understand, it was very hard to get an affidavit, which was a financial risk for everyone. The US government was not willing to take over the costs for these highly endangered Jews, although they knew about their fates.

My grandparental family Halpern had for example to pay 20.000 RM to get the necessary passports in Vienna. This was only affordable by selling the last pieces of jewelry of gold and diamonds of the family. For financing the emigration, they needed support by their relatives Julius and Olga Krupnik.

My paternal cousin Hilda Harmel, who immigrated as a seventeen-year-old teenager to England, where completed her school education but also her education in arts, was very clever. Her way to England was a pure adventure! Hilda appealed to a totally unknown distinguished gentleman in the British embassy in Vienna and begged him to get her an invitation to England for her otherwise she had to commit suicide. This gentleman, a British university professor, had a heart of gold and arranged the necessary invitation as au-pair to England – the beginning of her survival. Subsequently her parents could also travel to England. But Hilda wished to immigrate to the United States, surely an example of smartness. She searched for weeks in the yellow pages to find a person with the name “Harmel” to invite her…And in fact – she found the family of Lou Harmel in New York, who sent to the totally unknown Hilda Harmel an affidavit; now she could enter the US in 1939. What a story! And what a gesture of gratitude of Lou Harmel …

Meanwhile, Dora and Michael reached the harbour of Tel Aviv coming by ship from Marseille in February 1939. They rented a small furnished room in Rehov Geula—what a fall compared with their lifestyle in Vienna. The immigration to British Palestine was enabled by Julius Krupnik who gave guarantees for three Capitalist certificates to get visas, because the normal quota for immigration were consumed and no more were available.

Michael’s sisters Dora and Berta and their Husbands Joseph and Adolph and their numerous children already lived here in Tel Aviv. Also Julius and Olga Krupnik, who ran her fashion shop “Model” on the central and busy Allenby Street 29, were in Tel Aviv. Later some family members worked in this business: Dora, Dora’s (and Olga’s) brother Isidor Tausend and partly Olga herself. Soon Joseph Katz started his successful shop on Allenby Street, which became a vein of gold. Joseph was the type of successful businessman, who repeated his success from Vienna; only a handful businessman were able to do this; my cousin Hanan Tell (Joseph’s grandson) told me this.

Meanwhile, my mother came after a year of preparing courses (one teacher was Golda Meirson) for a following life in a Kibbutz as a Hachsharah (apprentice) to the famous Kibbutz Degania Beth near Lake Genezareth and spent a lot of time here and in Kibbutz Alumot near Poria. She met in Petach Tikwa a girl of Poland who suffered from nightmares; she often cried in the nights, and people said that she had been in a concentration camp. She informed my mother about many captured Jews in eastern territories and that they were killed. This was the first time my mother heard such narrations, which were for most people hard to believe.

In Degania Beth, founded in 1920, the collective socialist economical system was realized. All people worked together; everything belonged to the community. This Kibbutz was a branch of the oldest Kibbutz in Israel, Degania Aleph, founded already in 1910. It is the birthplace of Moshe Dayan (1915-1981) the later Hero of the wars of 1948, 1956 and 1967, general and war minister.

But this was later. We are at the moment at the beginning of Second World War, which started with Hitler’s attack on Poland on September 1, 1939. What would this mean for the Jewish population? Nobody knew at this time.

PART TWO

The beginning of WWII with the invasion of Poland was a catastrophe for the Jischuw. Meanwhile, Hitler conquered Poland and won all along the line. Paris collapsed in a debacle and Western Soviet Union fell into the hands of German Wehrmacht and the SS. Millions of Jews came under German occupation.

My paternal relatives in Haifa lived in fear about Max’s only brother in Zurawno, near Lemberg; as the following history showed – with good reasons. Their family in Zurawno was killed, a couple with one son, probably in 1941. We never heard about them. They vanished without a sign from this world.

Fritz, my father worked in his father’s antique shop “Armon” on Rehov Herzl in Haifa. My mother Trude (Shoshanna) lived after her time in the Kibbutz in Rehov Geula in Tel Aviv and tried to learn tailoring.

My grandfather Michael was jobless, and it was very bad without money in Tel Aviv. He decided in autumn 1939 to return for a while to Paris. He planned to sell the rest of his clothes, furs and fabrics from Vienna in Paris and with the earned money found a shop in Tel Aviv. Paris seemed safe, the Maginot line gigantic and the French army strong. Nobody could have imagined that Hitler could enter Paris on June 12, 1940, after a short campaign.

Very soon after, my grandpa fled to southern France to escape from the Wehrmacht and the Gestapo. For me, it is totally unclear why he remained in France so long. Relevant papers show that the famous author Manès Sperber was kept as prisoner in the internment camp, Les Milles, between May and December 1941—at same time as my grandpa. My grandfather was previously in Camp de Vernet in Ariège, whereArthur Koestler was also imprisoned. The legal source for this was the act about internment by the Vichy government from October 4, 1940.

From 1940 began the transports of Jews to the east as Manès Sperber clearly described, to Generalgouvernement. The Nazis told the Jews that they would work there and get enough food. Many Jews volunteered to these transports. My grandpa wished to be transported to the “East” because he was told he could go to a spa and experience good conditions for becoming healthy. A French doctor in the internment camp shouted roughly to Michael: “Are you crazy? No one ever came back!”

Michael cheated death. He had contacts with Olga Krupnik, who could buy him freedom from the Vichy government. How did this work? I don’t know, and there is no one alive who could be asked. Five minutes after twelve, Michael left Les Milles and was lead by a paid guide over the Pyrenees to Spain. He got a ship passage to Havana, where he arrived in early 1942. A reunion with Julius and Olga Krupnik, Leo and Hilda Weizenbaum, Harry and Zita Lax with their son George; Isidor and Fritzi Tausend and others followed. Michael was sick and poor, but alive.

Nobody knew at this time that the “Wannsee Conference” had taken place on January 20, 1942, where the “Endlösung der Judenfrage”, the final annihilation of the Jews in Europe was decided. President of the meeting was Reinhard Heydrich, the keeper of the minutes for Adolf Eichmann.

With the Wannsee Konferenz started the final phase of the annihilation of the Jews. From now on, no Jew was allowed to leave the German occupied countries. Shortly before this, Heinrich Himmler forbade the emigration of Jews on 23 October 1941. Michael left Vichy France after this date…

Michael had no work, no flat, no future in Cuba – only a small rented apartment: he lived from the support of the Joint Distributive Committee and jobs here and there. His sorrows about his two sons Ernst and Robert, who served as soldiers in the Royal Army in Egypt and later Northern Africa and Italy, accompanied him. His heart disease became worse, and when he returned to his wife and Tel Aviv at the beginning of 1946, he had a heart attack.

Meanwhile, my father and mother were introduced to each other, as arranged by the two mothers who met by chance in Tel Aviv… and they were married on 30 June 1946 in Tel Aviv. The circumstances are described in my book. The young couple used to live in Haifa in my grandfather’s house, first in their apartment and after some time in a new furnished two-room apartment. Everything seemed to be happy. I was born in November 1948 and got the Hebrew name “Ilan”, my brother Michael was born in June 1955.

Meanwhile Robert had left Palestine, studied in London and finished his studies of Pharmacy in Vienna. The older brother Aron became a police officer in the British Palestine police and later an officer in the Israeli police. His daughter, Zipora, was already born in 1939.

The Krupnik family lived now partly in Israel: Gedalia (“Fredl”) and his wife Charlotte in Rehovot; they had four children. Grete and David Pik lived in NY and later Canada; they were divorced and had three children. Their son Robert Pik is living near Tel Aviv. Daughter Zita and her husband Harri Lax emigrated to NYC; they had one son, George Lax (1935-2005). George married Gila from Sweden and had two children: Peter (living in NYC) and Veronica, married Gönc, who live in Stockholm.

I translated parts of my essays in recognition of the great achievements of Julius and especially Olga Krupnik for my family! We are thankful until today.

Dr. Ilan Fellmann,

Vienna,

17.7.2015

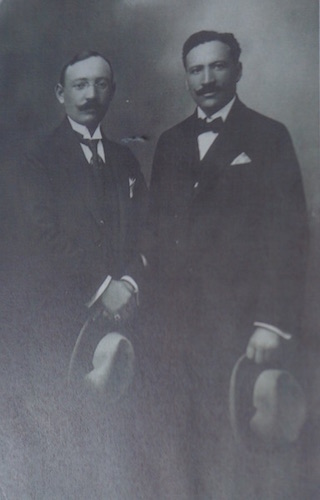

Photos: (1) Max and Adele Fellmann, wedding in Vienna Stadttempel (1915); (2) Hilda Harmel Pierce (b. 1921 in Vienna). She is the daughter of Julius Harmel of Zurawno; (3) Michael and Dora Halpern and their sons Ernst ('Aron') and Robert (1923, Vienna). Michael was born in 1889 in Horodenk and lived in Cernovce (both are now in Ukraine). He came because of WWI with the entire Mayer-Halpern Family in 1914 to Vienna, fleeing from the Russian army; (4) Trude Fellmann in Vienna (b. Halpern in 1925); (5) Brothers Adolph Mayer and Michael Halpern (c. 1920 in Vienna); (6) Olga and Julius Krupnik in the 1950's. Olga is a sister of Dora Halpern and aunt of Trude Fellmann.

Permission to use the photos on this page granted by Ilan Fellmann on July 25, 2015.