Old Jewish

Cemetery in Lithuania Restored with the help of local townspeople

By Joel Alpert and Fania Hilelson

Jivitovsky

Overview

of the central section of Yurburg Jewish Cemetery

In 2001, a group of us - twelve descendants

of Yurburg, went to visit Lithuania in search of our ancestral roots. While on

a tour in the capital city of Vilnius, we arranged to meet a local Jewish

survivor Zalman Kaplan who was born and raised in Yurburg. Kaplan shared with

us his memories of the once vibrant Jewish Community in the old but forgotten

Yurburg. He shed a tear remembering the tragic loss of his family and friends,

and told us about life in his beloved native town that vanished in one day in

August 1941. Not a trace of the Jewish Community was left in Yurburg, except

for the old Jewish cemetery, hidden on a back road of a hill overlooking the

Neman river. Aged stones gave in to the relentless passage of time, overtaken

by grassy impenetrable weeds, the tranquility of the cemetery interrupted by

voices of rowdy teenagers throwing around beer bottles. Some of the tombstones

were gone altogether, stolen or reused by local construction workers. For

Kaplan, then 80 years old, to restore this unique showcase of the Jewish

Community, was a task of utmost importance, and he feared he would not live

long enough to see the task completed. Zalman had escaped the Nazi invasion of

Yurburg on June 22, 1941, at the start of the Nazi “Operation Barbarosa” to

invade Russian territory. He pedaled his bicycle out of town barely escaping

the advancing German troops behind him. He ultimately fought the Nazis in the

16th Lithuanian Brigade of the Red Army composed mostly of Jews. By the end of

September 1941, the 1000 Jews who lived in Yurburg before the war were all

gone, the majority of them murdered by the willing local Nazi collaborators in

Lithuania.

Not a single Jewish person returned

to Yurburg after the war, and the cemetery, standing alone and deserted in the

hinterlands of Lithuania, became the only reminder of the hundreds of years of

Jewish past. Albeit ironically, the tombstones, some of them still intact,

served as proof of the vibrant Jewish life that once was. As is well known,

many Jewish cemeteries in rural towns of Eastern Europe have been desecrated.

Headstones have been removed and recycled in construction projects or roadways.

Many Jewish cemeteries were redesigned into soccer fields or parking lots. Yet,

this cemetery of Yurburg, in the western back roads of Lithuania with more than

300 identifiable headstones had miraculously survived. We could not refuse the

urgent request to help Zalman accomplish his life’s goal.

First, we set up a not-for-profit

organization and called it “Friends of the Yurburg Jewish Cemetery.” In 2005,

we made a second trip to Yurburg. This time we requested a meeting with members

of the Jurbarkas (the Lithuanian name of Yurburg) town council to discuss the

restoration of the cemetery. Eight of us came into the meeting, When all was

said and done, the town council promised to cooperate, but admitted they had no

money to allocate to a cemetery, much less to the “Jewish cemetery” They told

us that this was not the first time they were asked to help, yet, as they

stated, “there was never any follow-up”. We sensed an implied “dare” in their

words to actually follow through.

With the help of other family

members and other descendants of Yurburg, the “Friends” raised $5000. With that

money in hand, we contacted the small Jewish community of Kovno (Kaunas) and

asked for their help to arrange construction of a new entrance gate to

replicate the original one destroyed during the war. Motl Rosenberg, a son of a

Yurburg survivor Dobba Rosenberg, who still lives in Lithuania, began to work

on the design and construction of the new entrance together with the

municipality of Jurbarkas.

The project became a true test for

the “Friends”. Could we accomplish such a monumental task being so far away

from the restoration project? As time would show, we could, indeed, and the

entrance would be completed in November 2006.

Rejoicing at our first success, we

embarked on another fund raising campaign to tackle the next task of rebuilding

the fence around the cemetery, Zalman’s ultimate goal. We managed to raise

another $15,000. Then, unexpectedly, help that might have been “b’shert” came

our way.

We received an e-mail from Rabbi

Edward Boraz of Dartmouth College Hillel in Hanover, New Hampshire who was

looking for a site for his “Project Preservation, 2007”. The project was in its

fourth year in which about 20 students, both Jewish and non-Jewish, travel to

Eastern Europe, visit Auschwitz and spend a week restoring an old Jewish

cemetery in a small town, once home for Jews before World War II. Rabbi Boraz

inquired if he and his group could work on “the cemetery in Yurburg”. The

“Friends” were elated and welcomed the offer. We hoped that, although the

cemetery was under the jurisdiction of the town municipality, construction of

the fence by American volunteers would be permitted.

In the summer of 2007, 18 Dartmouth

college students along with Rabbi Edward Boraz, a faculty member of Dartmouth

College, Joel Alpert and his spouse Nancy Lefkowitz of the “Friends” with one

more resident of New Hampshire went to Yurburg for five days to work on the

installation of a 300 meter-wrought iron fence constructed in Lithuania and

designed by Dartmouth Hillel. The group was joined by eight English class

students from the local Lithuanian High School who came together with their

enthusiastic teacher Asta Akutaitiene to help with the construction project.

The American and the Lithuanian students worked tirelessly to dig up and

upright the overturned headstones covered in mold and layers of thick moss

accumulated through many decades after the war. They dug holes, hauled sections

of the fence and cement to the site to anchor the structures. Even members of

the town council turned up to give a hand in the general clean up, removing

trash and weeds into the trunks of their own private automobiles. It was a

stunning and spectacular sight, and the spirit of comradeship was overwhelming.

Asta Akutaitiene (shovel in hand) with

the Lithuanian high school students digging up a long forgotten headstone

This joint effort became one of the most important

parts of our cemetery project. It was the first time the Lithuanian students

had ever met any Jewish people. The Lithuanian students bonded with their

Dartmouth counterparts, and both groups took pride in their mutual work. There

was now a common ownership of the amazing project that restored a forgotten

past.

We became convinced that if these Lithuanian students

would ever hear an anti-Semitic remark they would not let it pass. These

students knew – Jews are not like some of their friends might be telling

them.

New entrance (left) constructed in 2006

by the “Friends of the Yurburg Jewish Cemetery” and the new fence (right)

constructed in 2007 by Dartmouth College students

During their stay in Lithuania, the Dartmouth College

Hillel group met two amazing young Lithuanian women, who helped with the

project.

One of them was Ruta Puisyte, a young Lithuanina

woman, a graduate of the Vilnius State University. She wrote her bachelor’s

thesis on the “Murders in Jurbarkas” because she wanted to learn more about

this hidden part of the Lithuanian history. She once asked her father about the

old cemetery in Yurburg, close to the village where she grew up. He told her

that “horrible things had happened there”, but would not go into greater

detail. She wanted to know more. Today, she is an expert educator on the

history of Jews in Lithuania and works as an Assistant Director of the Yiddish

Institute of Lithuania.

Officially Lithuania takes no responsibility for the

murder of its Jewish citizens during the Shoah, in spite of the fact that 95%

of the Jews of Lithuania perished at the hands of Nazi collaborators.

Anti-Semitic remarks are still heard in the country despite the fact that the

Jewish community is very small, numbering only about 3500.

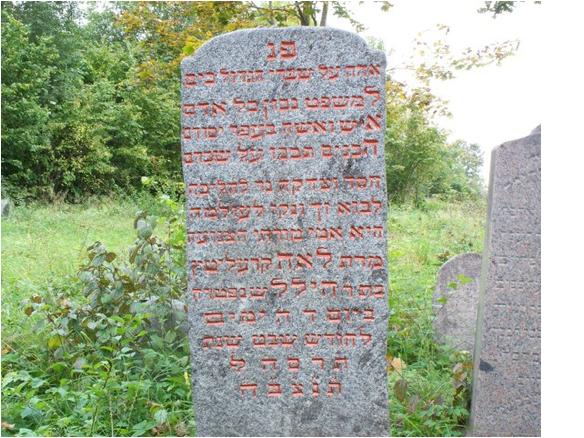

New

fence with the old decaying Russian era fence behind it

The Darmouth College students

also met Riva Vaiva, a local Lithuanian woman who had wanted to learn more

about the mysterious inscriptions carved on Jewish tombstones in the Yurburg

cemetery. As a high school student she would often come to the cemetery on a

warm summer day to read in the shade of an old tree enjoying the tranquility of

the peaceful setting. She began to wonder about this deserted corner of Yurburg

and wanted to know about the people buried in this cemetery. She looked at the

strange markings on the headstones. When she found out that these were Hebrew

letters, she took a course in the Hebrew Language at the Vilnius University.

Over the past years she has independently undertaken a tedious and artistic

task to clean and re-inscribe the headstones in the cemetery, hoping to help

preserve a page in the history of the Jewish community of Yurburg. Under her

craftsmanship the tombstones now have colorful letters and the carvings are

legible. Rita has taken on an added responsibility to ensure that the local

authorities fulfill their legal obligations to preserve the cemetery by

clearing the bush and tree overgrowth, cutting the grass and removing trash.

Rabbi Edward Boraz (left) translating

headstones, with RiVa Vaiva on his right

Headstone of Leah Krelitz, great-grandmother of the

author Joel Alpert, re-inscribed by RiVa Vaiva

Thanks to our efforts the Jewish community of Yurburg,

tucked away in the western edge of Lithuania, will not be forgotten. In 2005,

the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe opened in Berlin, the first such

official memorial to the Shoah in the united Germany. In the Family Fates’ Room

of the Information Centre located beneath the Memorial, there are 15 displays;

among them is one about our Yurburg, featuring the Krelitz family. The display

offers many photos, including the marvelous Wooden Synagogue of Yurburg. A

video clip, restored from a film taken in 1927 reflects a day in the life of

Yurburg in all its vitality which would be destroyed 14 years later.

The “Friends” are proud of their accomplishments in Yurburg,

a small town that could have easily been forgotten. We are grateful that the

Jewish Cemetery is being restored and cared for not only by the Jewish

descendants but also by its local Lithuanian residents. We celebrate the mutual

contributions of these two groups that will promote the healing of the wounds

of a horrible past.

Zalman Kaplan, our landsman from Yurburg died shortly after

the project was completed. It is through the synergy of the young local

residents of Yurburg, and us, the descendants of the town working together with

Rabbi Boraz and the Dartmouth College students that Zalman’s Kaplan’s life task

was finally completed.

We hope our project will inspire others to contribute to the

preservation of our Jewish past in the small towns of Eastern Europe.