Max was born and raised in Yurburg, Lithuania. He was a Zionist and upon graduating high school, he was ready to immigrate to Palestine, but upon consultation with the Zionist group, he was told that he must have a profession to be helpful there. He was told that they were building a new country and a civil engineering degree would be very valuable. He left Yurburg in 1921 and went to earn an engineering degree in Germany. He had been sent an entry permit to the United States by either his uncle Harry Ellis or his uncle Bill Krelitz. Upon graduation in 1925 he made alyiah to Palestine instead of going to the United States. He sent the entry permit to his brother George (Zerry), who did come to US and settle in Detroit. Max settled initially in Jerusalem and worked in an architecture office there. In his early years there, he designed some of the first new housing in Jerusalem outside the old city, in Neve Yakov. The British destroyed this neighborhood and the land became part of Jordanian Jerusalem in 1948. Today there is an Israeli army camp built on the spot.

In the 1930s Max designed at least two apartment buildings in the new "Bauhaus" style in Tel Aviv. These buildings still exist. His cousin Ezra Kapshud, also a civil engineer, who was born and raised in Israel, said that Max is considered the "Father of the profession of land appraisal in Israel."

Yitzhak Zarnitsky, Max's son, relates that Max's first job in Eretz Yisrael was for the archetecture engineering firm Heker and Yelin in Jerusalem as chief engineer in charge of building the Neve-Yaakov neighborhood of Jerusalem between 1925 and 1926. This photograph is in front of the Hotel San Remo that still exists on Hayarkon and Alenby Street in Tel Aviv.

He married Bella Labok, originally from Moscow, and raised two sons, Yossie (Yosef) and Yitzhak, who both became successful civil engineers. Max designed several apartment buildings in Tel Aviv in the Bauhaus tradition and eventually became the Chief Surveyor in Israel. In that capacity he traveled to US in 1950s, and visited family in Milwaukee and elsewhere. His home was always open to any family members who came to visit Israel. His home in the 1950's was across from the Mann Theatre in Tel Aviv on Marmorik Street. He and Bella eventually moved to northern part of Tel Aviv, at 10 Biltmore Street.

Max always served as an inspiration to his family all over the world. Bella and Max always welcomed any family members who came to visit or live in Israel. They were warm and wonderful people.

Nossun Kizell, son of Moshe Tuvia Kizell and Rochel Laya Feinberg, one of seven daughters of Rafael Feinberg, son of Naftali, was born in Yurburg on April 14, 1900. Moshe Tuvia and his two brothers came from Finland (which I only learned of this past year!).

The Kizell family owned a bakery in Yurburg, so although they were not wealthy, they always had bread to eat.

My father's recollections of Yurburg were pleasant and he had acomfortable childhood there. He bragged of having "nickel ice skates," quite a status symbol compared to the "wire hangers" that his brother Hertz had (as related by Hertz's daughter Greta Kizell Florence).

I assume his house had two stories as he said that he kept his "collection of pistols" (for target practice only) upstairs. He liked school, attending a "cheder" where he learned to read and write Yiddish and Hebrew. He also learned secular subjects. He often recited a Russian poem, which began with the words "buryam gloyit." He never knew in which language the secular subjects would be taught that year, so he ended up speaking Russian, Polish and Lithuanian in addition to Hebrew and Yiddish. He said that in the first grade he was the best in the class in Mathematics, justified by being the quickest to answer the question, "How much is one million take away one?" Nonetheless, his favorite memory about cheder was the last day of the "z'man" (semester), when he threw all his schoolbooks into the bakery oven in his house.

Nossun was always a good sleeper and he told us of the time that his mother said "let him sleep a little longer" even as a fire was threatening their house. This may have been the "Great Fire of 1906."

On his 12th birthday, the news of the sinking of the Titanic reached Yurburg. My father claimed that this was the first news item that he personally remembers from beyond his "shtetl world."

In 1925, at age 25, Nossun Kizell came to Canada to join his three older brothers and one sister in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. There he became Norman, worked by day, and went to night school where he learned to read and write English correctly, albeit with some idiosyncracies. When he wrote, there never seemed to be spaces between the words, or even any other blank space on the page. We still don't know whether he was trying to emulate Torah script, or just trying getting the most out of each page of paper. He walked to and from work to save the weekly 25-cent streetcar fare allowance he was given by his older brothers. He learned enough spoken French to direct his workers. I often heard him introduce himself as "Ici Monsieur Normand Kizell marchand depe aux quiparle" (Here speaks Mr. Norman Kizell the hide dealer), when calling the butcher and trappers that he was planning to visit on his next "week on the road." On such trips, our biggest worry was that the Mack truck would break down and we would have to get him in the Packard. His biggest worry was that he would be caught with deerskins out-of-season or overweight at the weighing station. At age fifty-six, he was able to retire from his very successful hides and fur business. At this time he began a new career in real estate, which was similarly successful. He bought, sold and managed properties in and around Ottawa. This included carrying with him (at all times) a peach basket full of keys as he visited the tenants to collect monthly rent and to atttend to complaints personally. At the end of the day, he would water his trees with pails of water (not a hose), hammer straight loose nails he had collected. His office had a large map of the local counties, with his parcels (pronounced "possels") shaded in. He was proud of his physical strength - in the early years he would balance and carry around a ladder with his teeth. Later on, he would challenge his daughters' suitors to brick-lifting contests. (My eventual husband was reputedly the first to decline the contest.)

Back to 1935 - my father was single, good looking and "economically promising," but he did not want to marry a "higa" (someone "born in America"). He travelled back to Lithuania on an extended visit to look for a bride. Although his parents and most of the children were already in Canada, his two sisters, Chiene and Gittel, and his brother Dovid still remained in Yurburg. During his visit, he met, courted and married Sonia Gitkin of Shavel (Siauliai, the second largest city in Lithuania at that time). They honeymooned in Paris and sailed back to Ottawa on the "Lusitania."

His greatest pleasure for the second part of his life was driving his wife, children and grandchildren, his many siblings and their families and many guests, for boat rides on his Peterborough outboard and Criscraft inboard motor boats at his summer cottage located just outside of Ottawa (in what is now called Nepean).

One of these guests stands out in my mind. In the summer of 1952 (approx.) we received a lone guest from Israel - Max Zarnitzky, whose family "lived in the same house" as the Kizells in Yurburg. Helen Kizell Beiles, my father's youngest sister, who was born in Yurburg and who now lives in Montreal, confirms that the homes of the Zarnitsky and Kizell families did in fact share a common wall. Max had left Yurburg for Palestine in 1925 with Sam Kizell, Nossun's brother. Sam was not up for the task of building the country - in which his role was to pick up stones in the field, so he joined the Kizell family in Canada, and continued his active role as a Zionist in Ottawa. Max stayed in Palestine married, had two sons, Yossi and Itzhak, and went on to become known as the "father of land surveying" in Israel. When Max returned to Israel from his visit in the 50's, he had his older son Yossi write to me as a pen-pal, and so the friendship between the Kizell and Zarnitsky families continued to the next generation and more. On one of my first trips to Israel with my husband (about 1967), Max and Bella Zarnitsky reciprocated my parents' hospitality. We stayed a night or two with them in their apartment on Biltmore Street in Tel Aviv and they took us to a Habimah Theatre production of Arthur Miller's "The Price." They had two pairs of seats and they insisted that my husband and I sit in the better seats in front, while they took the pair in the back of the balcony. When my daughter Gina Pearl Gotlieb (Ra'anana) made aliyah to Israel, she stayed with Itzhak and his wife Nava for two months. A few years later, the bris of Gina's son Erez was held in Itzhak and Nava's garden. Nowadays, when we or either Zarnitskys' introduce ourselves to others, we do so not just as friends, but always mention that our fathers were "landsmen" in Yurburg.

In addition to being a devoted family man, Norman Kizell's two other principal values were his good name in the community and his acts of tzedakah. He founded and funded the Ottawa Hebrew Free Loan Association. Sonia Kizell was a founding member of the Ottawa Newcomers Committee, a ladies group that welcomed and integrated new residents to the Jewish community.

Together with Helen Kizell Beiles, Sonia founded the Rachel Leah Kizell Chapter of Mizrachi, (in memory of Rochel Leah Feinberg Kizell who died in Ottawa in 1941). The chapter is still active to this day.

Norman Kizell passed away in October 1973 (12 Heshvan). Never one to leave all his eggs in one basket, he left funds for ten yeshivas to say Kaddish for him. He had lived to enjoy the birth of his nine grandchildren. Norman's widow Sonia passed away in 2003.

Norman and Sonia descendant include three daughters, nine grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.

Born in Yurburg, January 13, 1917

Yankel Chossid was born in Yurburg in January 1917 to a family with several brothers and sisters. His father, Eliezer, was a building contractor. His mother died when Yankel was very young and his father remarried. The couple then had a daughter and twin sons. Yankel grew up in Yurburg, attending the Talmud Torah School and Hebrew gymnasium in Yurburg. As a young adult he worked in the Komertz Bank in Yurburg owned by the Bernstein family. In that position Jack learned much about the business dealings in the town. By the time Jack left Yurburg at age 20, he knew virtually every Jew in the town.

In the summer of 1937, Yankel left Yurburg to immigrate to America with the help of his older brother Hyman, who had already immigrated to Chicago. On August 1, 1937 Yankel left Kovno, Lithuania by train to go to Hamburg, Germany. He left Hamburg on August 4, on the SS Harding and sailed for New York, arriving there on August 14, 1937. From this point on Yankel Chossid became Jack Cossid. The next day he arrived by train in Chicago and was met by his brother Hyman.

Hyman had left Yurburg in 1921 at age 16 along with his sister Sylvia, age 14. Hyman became a buyer for Goldblatt Brothers, a large Chicago department store. Jack accompanied Hyman on one of his buying trips to New York. On that trip Jack met Linda, an office worker at business contact in New York. Jack was immediately smitten by Linda, a sweet shy young lady from Brooklyn. In spite of Linda's reluctance to be courted, Jack persisted and the couple grew close in the week Jack was in New York. They then corresponded and eventually Jack returned to New York, and they were married on July 22, 1945.

When the war broke out, Jack joined the US Army. He served as a quartermaster and then as a translator (making use of his knowledge of german, Lithuanian, Yiddish and Hebrew) at the Prisoners of War camp at Camp Grant in Rockford, Illinois. He had five people reporting to him. In Jack's home a portrait of Linda is displayed, in her wedding gown, drawn by one of the German prisoners.

After the war Jack learned that the whole family left behind in Yurburg was murdered, including his father, stepmother (whom Jack always referred to as his mother, since she was the only mother he ever knew, as his birth-mother died when Jack was very young), a half-sister and twin half brothers; in fact, virtually every Jew who had remained in Yurburg has been murdered by their Lithuanian neighbors.

The Eliezer Cossid Family in Yurburg (about 1925) Jack Cossid in center bottom row

Only one sister, Dorothy, who had been living Kovno, survived the concentration camps, having lost her husband and a young daughter. She eventually remarried and settled in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (died in early 2003).

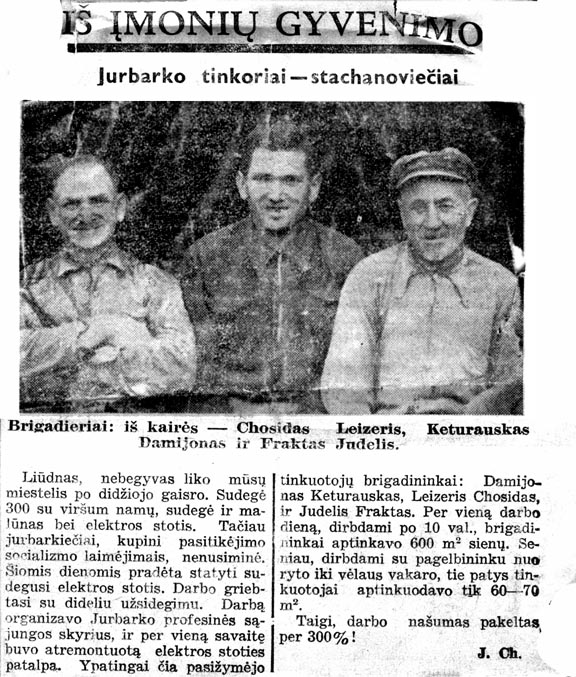

Jack has a scrapbook and photo album of Yurburg, including a newspaper article about an award to his father, who was a building contractor and builder in Yurburg. Jack was told that his father was murdered at the site of the Jewish cemetery, and his body thrown down the well that still exists there to this day. Over the years, Jack, like other Holocaust survivors, has always searched for information about the Holocaust in his town. He has accumulated a wealth of information, remembering minute details of the town he had left, a town that no longer exists for Jews.

Jack and Linda created a dry cleaning business in Chicago and raised two daughters, Gail and Benay. Linda passed away in May 2001. Jack now has four grown granddaughters. He volunteers at Jewish Centers often giving courses in Yiddish and on current events. He gladly speaks to anyone who wants to know about Yurburg or their relatives in Yurburg.

Above left: Jack Cossid on the right and and his brother Fievel Chossid in his uniform from the Lithuanian Army. Fievel spent 18 months in the army (1931 or 1932).

Above right: Jack's twin helf-brothers Moshe-Heshelah and Zalman- Heshka. Hitler killed them and Jack's half-sister, sister Basalah.

From the right, Jack Cossid, his sister Dorothy and brother-in law-Peisach Millstein. Photo taken in Kovno on July 30, 1937, one week before Jack left to immigrate to the United States.

Right: Eliezer Chosid (Jack Cossid's father) about 56 years old, and was taken a few months before Jack left for the United States.

As related in other parts of this book, it was the editor of this book, Joel Alpert who found Jack in 1994, while searching for information on family who had remained in Yurburg. Jack knew them all, the Eliashevitz and Krelitz and Naividel families. Joel's mother's first cousin, Moshe Krelitz was Jack's mentor and a very good friend. Joel had not known about Moshe Krelitz, and he learned much of his own family from Jack. Joel also discovered long lost Krelitz family in Mexico City, Max Sherman-Krelitz (nephew of Moshe). Max's mother Leah had immigrated from Yurburg to Mexico in 1938 and was known to Jack in Yurburg. After his mother's death, Max had discovered a leather briefcase containing over forty handwritten letters in Yiddish from Moshe Krelitz, his sisters and brother, and several friends. These letters were written between 1938 and 1941. The letters did not have much meaning to Max and his sister Esther, mainly because their mother Leah Sherman-Krelitz found it was too painful to talk about her Yurburg family. The trauma of learning that they had all been killed was too overwhelming and she mostly kept her grief deeply inside. Even though Max and Esther read Yiddish, it was too difficult to decipher the letters, furthermore, they did not know much about the tragedy described in such heart-wrenching words in the letters. Joel obtained copies of the letters from Max and sent them to Jack. With Linda's help, he translated the letters into English (see the section by Max Sherman and the translated letters that follow). Now with family background provided by Joel and the clear translation provided by Jack and Linda, many of the mysteries of their family's past began to unravel for both Max and Esther. It was painful for Jack to read letters written by his dear friends nearly 60 years after their murder. It is through these letters that Jack learned more about the destiny of his hometown and even about his own cousins who perished along with the others during the tragedy of the war. Jack said that after this experience he no longer believed that there might be anything impossible in this world.

Due in part to our newly gained knowledge of Yurburg and to the stories about families left behind told by Jack, we began to organize a trip to Lithuania (discussed in an article in this appendix by Fania Hilelson Jivotovsky). A group of Naividel and Krelitz family members traveled to Yurburg, and so began the long road to discovery of our fascinating past, and of the people who were once part of our family and our history.

Jack would have wanted to participate in the trip, but Linda, his dear wife was gravely ill. She passed away the day the group landed in Lithuania in May 2001.

For nearly ten years now, Joel has been referring people seeking information about lost family members from Yurburg to Jack. Painful as it is for Jack to remember his friends and family, who perished in the war, he takes joy being able to tell the callers about their family from Yurburg

The American descendents of Yurburg are indebted to Jack for sharing his memories of Yurburg. Jack will always be our true friend and our beloved Landsman!

My father, Benjamin Heshel Craine, after whom I am named, came to the United States in the early 1900s. At the time, he immigrated to Minnesota, later moving to Detroit. In 1919, he opened a portrait photography business that grew to be the largest, most highly recognized, and respected portrait studio in Michigan. Under his guidance, the studios counted among its clients, the entire Ford family, starting with Henry, Sr; the Dodge family, the Buicks, many of the Detroit Tigers, and most of the other prominent families in the area. Late in life, in his early 50s, he married for the first time. My mother was twenty years younger, and she came to work in the business. Soon afterward, she became pregnant; then, he was diagnosed with cancer. When he died, my mother was six months pregnant, and she was left with a very large business [at the time, the studios employed around sixty people, including many of my father's extended family including many from Yurburg].

Unfortunately, since she had been married for only a short time, there were those family members that felt he should not have willed the business to my mother, and they attempted to take it away from her. All of the responsibilities, including me, managing the business, and the necessity to defend her ownership of Craine's Studios, made her a very strong woman. As a result of this family rift, I grew up knowing few of the Craine family. My mother remarried when I was five, and, together, she and my stepfather ran the business. Growing up, on the weekends, I often helped in the business. After graduating from University, I returned to Michigan and began to work full time at the Studios.

I must point out that my mother always spoke of my father with reverence. I also knew that many of the people working at Craine's Studios worked there with my father, and, from them, I came to know that he was a great man, leaving me a wonderful legacy. Nevertheless, in spite of the fact that my mother did not want to take away from my relationship with my stepfather, I still knew little of my birth father. At our main office, we had a locked cabinet that contained a variety of items, including a stack of 16mm films on the bottom shelf. From time to time I would ask my mother about the films, and she would say, "They were your father's; leave them be." For whatever reason, I respected that request.

It was some years later, and we sold the Studios to a large, national, company, for whom I went to work. Shortly thereafter, we moved our headquarters, and we had to dispose of the locked cabinet. Although my mother had retired and was living in Florida, her request with regard to the films to, ". . . leave them be," continued to resonate. I moved the films to a shelf at home in our basement. There, they sat for another year or two. One rainy day, I went downstairs, took the films, a 16mm projector, and a screen, and I began to view them. Frankly, I knew little of what I was seeing. I did recognize some people in the films who had been working at the Studios, and it was clear that some of the movies were taken in Europe. Still, I could not recognize or identify anything other than those people who I knew from work. Then, in one scene from Europe, I saw my father pictured with two older people, and I was both shocked and overwhelmed. I stopped the movie, rewound it, and called my wife, Vicki downstairs. I replayed the film, and I said to her, "Look, those people must be my grandparents." Since I look a lot like my father, it was easy to see the strong family resemblance that transmitted from my grandfather to my father to me. Frankly, I had never seen photographs of any Craine family members, so this was quite overwhelming. Not knowing most of the people in the movies, and remaining faithful to my mother, once again I returned the films to the shelf to ". . . leave them be."

Though I have said that I remained apart from almost all of the Craine family, from time to time I did hear from my mother about members of the family with whom she had stayed in touch; these were all more distant cousins who had not taken sides many years ago when my father died. I did not know how most of them were related, but there was one set of Craine cousins with whom we maintained a relationship. Max Craine had run the Frame Shop for Craine's Studios when my father was alive. Later, he went into business on his own, and, still later, his son, Joe, joined him in the framing business. When I came into the business, we began purchasing some frames from Max and Joe, and I was pleased to develop a relationship with some of the Craine family. Also, since at the Studios we produced many High School yearbooks, one year I had the pleasure of working with a student yearbook editor, Sandee Tobin, who it later turned out to be another cousin. [These pieces of the puzzle are relevant; bear with me.]

After viewing the films for the first time, another year passed, and Max died. My wife, Vicki, and I made a condolence call to his family. Standing there in the middle of the mourners, all of a sudden, we both noticed four elderly women moving toward me, looking at me, frankly, as if they had seen a ghost. They came up, took my hands, looked them over, and said, "You must be Ben." The four women were Max's sisters, and all of them had worked at the Studios years before. Growing up, they lived in Altoona, Pennsylvania. When their father died, my father moved them to Detroit, gave all of them jobs in the business, and became a surrogate father to them; I never knew of that connection. I mentioned the films to them, and the eldest sister knew about each of the reels. In 1927, my father had filmed family in Detroit and Altoona, and then traveled to Lithuania, where he showed the movies to his family there. He filmed the family in Lithuania, and brought the films back to the United States so he could share them with the family here.

I asked the sisters if they would like to see the films, and they said they would. The next day, I took the reels and had them transferred to video, then invited them to my house. Of course, the movies were silent, and that was fine. I connected a microphone to the VCR, then to the eldest sister, and we all watched the movies together. The sisters were delighted and full of information. As we watched, they talked, and they identified many of the people in the films. They also told meaningful stories about those pictured, and, unfortunately, some of those stories included identifying family members who perished in the Holocaust. These were movies taken in 1927 in the town of Yurburg, Lithuania, showing people picnicking, boating down a picturesque river that ran through town, generally having a wonderful time, and even getting married in the town's old wooden synagogue, also later destroyed in the Holocaust. From the National Center for Jewish Film, I later came to learn that there is precious little original film footage available that shows people living happily in such a European shtetl. So, now I had a treasured film in which we had identified many family members, none of whom I had known or was likely to know. This film has been seen by several family members who never knew their grandparents, yet they saw them moving through the steets of Yurburg in the film; these were very powerful moments for them. The film is now achived at the National Center for Jewish Film at Brandeis University, so it can be a source of research and provide authentic film footage for filmmakers.

Remembering the student yearbook editor who was a cousin, after making the video, time passed, and a while later I got a call from Sandee; she had heard about the video, and she wanted to get a copy for her mother (Diana Berzaner Tobin, who had been brought to Detroit by her mother Itel in 1939 - Itel returned to Yurburg to bring her other daughter and husband back to Detroit, but they were all caught when the war started and were murdered). I was happy to make one for her. She was thrilled, and her mother was thrilled.

Time passed, and the original video with the narration sat in a drawer. Then, one day my wife, Vicki, took a call from a man who asked if I was the Ben Craine from the photography studios. She said that I was. He said that he had seen a copy of the video when visiting relatives in Florida and that he, too, was related. In fact the copy he saw was a copy made from the copy that I made for Sandee, the yearbook editor. His name, Joel Alpert, and we spoke. He explained that he lives in Boston and had been collecting information about the family, that, in fact, he had created a family tree and family history. I made a better copy of the film for Joel, and, when we later met in Boston, he gave me a book filled with information about this huge family, about which I knew very little. When Joel and his wife, Nancy, came to our hotel, we arranged to meet in the lobby. So that we would recognize each other, we designated a specific location.

When we met, Vicki said we did not have to worry about a specific meeting point because Joel and I look so much alike. As we talked, and as Joel continued his research, it was through Joel that learned that my father had immigrated to Minnesota, something I did not know. Joel also discovered that my father and his father signed each other's naturalization papers. Even stranger, Joel and I are exactly one year apart in age, sharing the same birthday, as were his grandfather and my father, who witnessed each others' naturalization papers. From Joel, I also learned that the video was now housed in two Holocaust Memorial centers.

As time passed, and we continued to correspond, another cousin, Ruth Ellis Stromer (grand-daughter of Reuven Eliashevitz, mentioned in the article above, "Home on the Iron Range") had the vision to begin organizing a family reunion. I agreed to help and to participate. As we began to plan, I had the opportunity to communicate with other family members, none of whom I had ever known. Our first reunion took place in Minneapolis. At the reunion, I had countless people come up to me to tell me stories how about my father had helped them get started. He had been a pivotal person in the family, providing employment for family members needing an opportunity to get back on their feet; making sure that family groups stopped in Detroit so that they could have family portraits taken at Craine's Studios; generally being someone any family member could turn to for help or advice. Quite a proud legacy for me, learning more about my birth father, a man who I never knew and about whom I knew very little. At the reunion, I introduced the film, telling this same story.

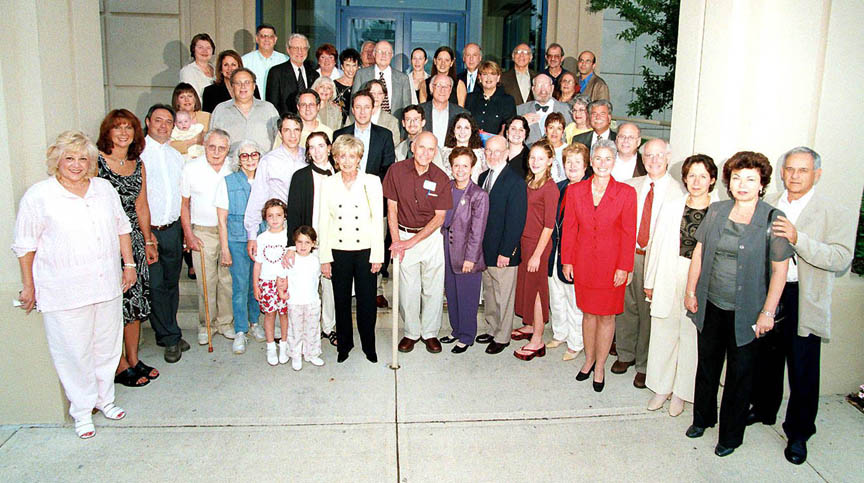

We have held three family reunions, ranging in size from 80 attendees to 120 attendees. The films, the video, have acted as a catalyst to gather people, all with ancestors who lived in the little town of Yurburg, Lithuania, extended family who now travel to our reunions coming from all over the United States, Canada, Mexico, and Israel. I am glad that I had the curiosity to save the films and the opportunity to find a member of the family who could help us learn about the people in the films. I am glad to have a cousin who is willing to spend literally thousands of hours collecting data and ensuring that our family stays connected. I am glad to have found, after so many years, such a large, warm, and welcoming family.

Moti was born on November 26, 1903 in Yurburg, Lithuania. He had a younger brother, Ilusha (Hillel).

His mother died when he was a little child, probably right after the birth of Ilusha. His father remarried, and Moti and Ilusha were raised by their Aunt Polly. Moti attended the Hebrew Gymnasium in Lithuania. Here he obtained his knowledge of the Hebrew language. Moti studied law in Kaunas and became an attorney of the law.

In 1936 his aunt Polly became seriously ill and in order to find a proper treatment, Moti took her to Berlin. Unfortunately, the treatment did not succeed, and Polly passed away during her stay in Berlin. Moti cared to bury her at the Jewish cemetery in Weissensee, Berlin.

Moti was married to Cheka Karabelnik probably in 1939 or 1940. They had one daughter, Elinka. Until the Russian army invasion of Lithuania in 1940, Moti and Illusha had a law office in Kaunas (Kovno). However, Moti and his family lived in Yurburg. After the Russian invasion, Moti and his brother, as well as all other private enterprises, had to close their business. Lithuania became a Soviet Socialist Republic and both brothers were offered high-ranking positions in the law administration of the Lithuanian government. Moti served as legal advisor the government and Illusha was appointed as judge in the Supreme Court.

On the day of the German invasion into Lithuania (in June 1941) Moti and his brother with his family were in Kaunas, while Moti's wife and child were in Yurburg. Moti could not return to Yurburg, and he and and Illusha with Illusha's family succeeded in fleeing Kaunas. However, tragically, Cheka and Elinka were murdered by the Nazis in Yurburg.

Cheka and Elinka Naividel Hillel Naividel . ..

Moti, Illusha and his family fled to Uzbekistan, where they spent the whole period of the war. As far as is known, both brothers worked in their profession. They shared a very small room together with other people. With the end of the war, they came back to Lithuania. Moti decided that he wanted to immigrate to Palestine. However, this was of course not possible, since Lithuania was under Soviet government, and the Soviet regime did not allow any emigration to Palestine. As a result of the situation, Moti participated in the "hijacking" of a Soviet airplane. He was a member of a group of about 100 people, who were willing to take this severe risk in order to go to Palestine. Unfortunately, it later turned out that the whole operation a fake and was organized by the KGB, in order to uncover the "Zionist elements" in Lithuania. Moti was sent to prison without any legal trial. He spent 8 years in Stalin's camps in Siberia. Moti used to tell that in the first night during his imprisonment, his hair turned totally white. Moti was imprisoned together with criminal prisoners. This was intended by the system, which sought to weaken the moral of the political prisoners. Luckily, Moti got a jot in the hospital of the camp. Most of the other prisoners were working under very difficult conditions in physically hard work, for example in the coal mines, building the railway etc. On the other hand, due to his work, he was subject to threats by other prisoners, who demanded that he provides them with drugs etc. In 1953, when Stalin died, Moti was released, as were millions of other prisoners. He was forbidden to return to Lithuania for a certain period (2 or 5 years). Moti succeeded in contacting his brother, who arranged his immediate return to Lithuania. In the beginning he had to hide, and only after a certain period all the papers for Moti's return became legal and he could start working. He then joined the largest Lithuanian metal plant as a legal advisor. Here, Moti worked for the next 20 years until his retirement in 1975. In 1954 Moti met Bella Rud, an opera singer and cousin of the husband of Moti's cousin Gita Abramsohn Bereznizky. They were married in 1955. In 1958 Bella gave birth to her only son, Benny.

During the last four years in Lithuania, already retired, Moti worked in the legal department of a toy factory.

Moti and his family made "Aliya" to Israel in May 1979. Moti and Bella settled in Kfar Saba and thereafter moved to Beer Sheva, while Benny joined Kibbutz Gaaton in order to learn Hebrew.

Even after his Aliya, at the age of 76 years, Moti remained was active he gave legal advice to newcomers and to people who had to fill out forms in order to get compensation from the German government. Moti always loved to read and had great knowledge of literature. He translated Ingmar Bergman's "pictures of a married life" into Lithuanian language. However, this was never published. Moti died on March 31, 1993.

Benny and Regina Naividel Kiryat HaSavionim, Israel February, 2003

The Mexican Connection

On December 22, 1996, being on vacation I started to search the Internet for some information about my mother's place of birth. I had searched several times previously for the town known to me by the name of Jurbarkas, Lithuania. On those previous occasions, when I had searched on the Lithuanian server, I had found only the town's geographic location and some brief references, but nothing was mentioned on the fact that in the near future more information would be included about Jurbarkas. On that occasion I used the Altavista search engine and it also mentioned Yurburg under the Yiddish name by which it was known to me, and to my surprise I found a whole page about Yurburg. I found the heading: "What happened to the Jews from Yurburg," and as an example: "What happened to the Krelitz family." This is my mother's family name! So with much excitement I started to download more information and found a photo in which my grandfather Meyer (Max) Krelitz appeared, the connection was so slow that it took what seemed like hours to appear in full. In these pictures I immediately recognized my grandfather because my mother had a similar picture of him that used to hang in the den of our house. There were also a couple of pictures of her brothers Liebl and Moishe Krelitz, who I also recognized from photos (I had never met them). Of course, I was very excited and crying, in a very emotional state of mind. A person named Joel Alpert, who was totally unknown to me, placed the material on the Internet. Further, on this page it was mentioned that there was a branch of the family in Mexico (where I live) but that all contact was lost. Based upon my own experience, I believed that they (the American side) felt the Mexican branch had very little interest, if any at all, in maintaining family connection. So I was very surprised to note that the page included a request to reconnect to the American family

I immediately called my sister Esther and could not really communicate to her my feeling of the moment. Afterwards, I called a first cousin (son of my mother's sister Riva who was still alive) by the name of Elias Guttman Krelitz, and he told me that he had received a letter from Joel Alpert whom he didn't know personally but knew he was the grandson of Tante Shile (his mother's Aunt Celia) and while considering how to answer, had lost the letter and hadn't answered it. At this moment I will pause to clarify the story.

On several occassions my cousin and I had spoken about creating a family tree but, as it often happens, we had deferred it for sometime "in the future." He had much more knowledge about the family for several reasons. In my case I had tried to talk with my mother about her past, and she always said there was nothing to talk about, nothing to say because all her family members other than her sister had stayed in Yurburg and were all murdered in the Holocaust. I was told that she had an uncle in United States by the name of William or Bill (Velvl) Krelitz but that he had passed away, and also a cousin, George Zerry (Zarnitsky) who lived in Detroit with whom she had occasionaly been in touch through the mail, mostly updates on news about weddings or bar mitzvahs and the like.

Here it is important to clarify some history which, I found out later, and which now explains the situation. My mother was the youngest of four brothers and three sisters, with a 17 year span between the oldest sister Riva (who immigrated to Mexico) and herself. Therefore, when my mother was born in 1917, my grandfather's brothers and sisters had already left for America by 1904, and even if she had cousins, uncles and aunts, for her they were very distant (being far away and with little comunication with them). Even though she might have seen some photos of them, basically her family consisted of the closest ones she had met in Yurburg. She had also mentioned that on her mother's side there was the Kapulsky family with whom they had not had a very good relationship. The Kapulskys had very little interest (if at all) in her branch of the family because they where very wealthy people in Europe in those days, although my grandfather and grandmother were not in bad shape economically, they were not in the same league, and for that reason they felt ignored. Also my mother lost her mother at very young age (3 years old) and as a result, the family ties with the Kapulskys were very tenuous.

I, by inference, and with a childish sympathy towards my mother, made the mistake to assume that it worked the same way with both sides of her family, and if some of the relatives existed, they probably had no interest to be in contact with her. Consequently, I thought, there would be even less interest in maintaining contact with me and my sister. Therefore, I grew up in a very small family not knowing of the large Krelitz family in the United States (seven aunts and uncles of my mother) and feeling that the subject of family was a forbidden topic.

In 1979 my mother made a trip to Israel and Europe with her sister Riva, and she mentioned she had visited with the Kapulsky family, who were very cold toward them. She also mentioned she had visited a cousin by the name of Dovid Leibke Abramshon who had a wife and two daughters, and they had a very warm reunion. However, I am not sure if they knew each other from Yurburg or not.

It is also very important for me to mention that my mom, who was a widow for many years, married again and then went back to Israel with her new husband and found out that her cousins Dovid Leibke Abramsohn and Max Zarnitzky had passed away, consequently even these relatives were gone.

When my mother had married again, my sister and I decided that because she married at an older age, there was the chance of her becoming a widow again, so we decided that we would keep her apartment, so that if she were widowed again, she would have a place to come back to. Unfortunately, that was not the case, as she passed away before him.

When my mother died in 1983, my sister and I went to her apartment and we found a leather briefcase, which she had brought from Yurburg. In it we found some family photos from Yurburg, which we had never seen before, and a set of letters she had received from her family in Yurburg, written in Yiddish between 1937 and 1941. I am fluent in Yiddish but cannot read Yiddish in script form. For sentimental reasons I decided to keep these letters even though it was not very clear to me who wrote them, or what contents of the letters were. I kept the letters even though my mother's practice was not to hoard, but rather get rid of things. The fact that she herself kept these letters made them very special to me.

Now, going back to my newly discovered family I traced through the Internet, I remember, I called my son Abraham (who lived in Houston). I was in a state of shock to have found family in the United States. Abraham immediately established contact with Joel Alpert and informed him about us. Joel was as surprised as we were, because he didn't know about our existence.

From there on a very close relationship developed, and we now have a record of E-mails and letters we have exchanged. In June 1997, my son Abraham and I made a trip to Milwaukee to meet many of our Krelitz cousins.

There is also another story about how I was contacted by Chana Magidovitch who survived the Holocaust and was a witness to the massacres in Yurburg [her testimony of the murders in Yurburg appear in Chapter 6.]

Chana Magidovitz's contact:

I can't recall the exact date, but after my mother remarried, one night I received a call, when I was half asleep, from a person who identified herself as Chana Magidovitz. She said that she was a close friend of my mother's from her hometown and wanted to find her because she hadn't seen my mother since the time my mother left for Mexico in 1937. She had found out that I was the son of Leike (Leah) Krelitz and she contacted me so that she could get in touch with my mother. Somebody had told Chana that my mother wasn't living in Mexico City any longer. By this time I was fully awake and I did not want to miss the chance to ask Chana about those from the town who had survived the Holocaust, since Chana herself was a survivor. Chana told me she survived because she had joined the Partisan Group. After the war she lived in the communist world and when she could leave she had done so, and was now traveling with her husband and speaking about the Holocaust in the Jewish communities. When she came to Mexico she asked the people that worked for the Jewish community about my mother. The advice she got was to contact me.

Chana told me that nobody else from the town had survived; I still hear her words: "they were buried alive and the earth shuddered for a couple of days from the movement of the bodies buried alive." Those words still overwhelm me. My uncles and cousins were among the people who were buried alive; my own flesh and blood were among the people she was talking about. Needless to say, after that I was so upset that I couldn't sleep well for some time. It had been some time since I had spoken Yiddish, and even though it might have been difficult, it was also very easy because, in spite of the fact, that I didn't know Chana personally, I felt close to her because after some many years she still remembered and was looking for my mother. I told her my mother was living in Miami Beach, Florida with her new husband and gave her the phone number. She said she was going to the United States and would for sure give her a call and try to see her. I know, she called because next day I called my mother and mentioned that Chana had called, but gave no details about our conversation (as I write these lines, memories still come to my mind of my mom and me as a five year old child going to the Red Cross to find out about survivors in the family or going to some other place where somebody would let us know about survivors from the Holocaust). Afterwards, when we spoke again my mother mentioned that Chana had called, and confirmed the news she always hoped would not be true.

I can only add that a couple of days after Chana's call, my mother, had a stroke and was hospitalized in Miami. We had always assumed the stroke was not related to Chana's call. However, today we are not so sure. Having partially recovered, my mother came back to Mexico where a couple of weeks later she passed away.

January 30, 1939 Yurburg

Dear Sister Leike, (from Moishe)

How are you? Are you having a good time? I did everything I could to send you some pictures of our Estherle, but they came out too dark because I took them inside our house, and that's why they are not any good. But now I am sending you some new pictures. She is even prettier in person. She is five months old now and she seems to be a very intelligent child.

You ask me if I can make a living. I can answer you that I could make a very good living, but the business climate is getting very bad, particularly for businesses owned by Jews. Most of the people of Yurburg say that we need to get out of Lithuania, to any other place, because Lithuania is now the worst place in Europe for Jews to live, particularly if there is war, and if Hitler's decrees are enforced in Lithuania as we presume that they would be.

Leike, what do you think of our planning to leave Lithuania? Do you think we could emigrate to Mexico? Do you think I could make a living with my skills? So now you don't need to be upset because you are not in Lithuania and don't even consider returning because everyone here will tell you that you are crazy to return. Things are very unsettled here in Europe, Leike.

Iztke Kopelovitz requests that you give his cousin a letter that he is enclosing in this letter. Tatke Lubin's mother passed away, also Zalman der glaze. Feigele Magidowitz sends her regards to you. Also Leizinke (Leizar) Peisachson says hello to you. Also my wife Dvora (Dora) and Esther send their love.

Be Well, (signed) Your Brother,

Moishe Krelitz

No Date (probably in 1939 - another letter from then reads very much like this one.)

No Beginning (probably from Leibel, but could be from Feige or Rochel)

.See to it that Moishe gets papers so he should be able to come to you. Things are not good here with us. The whole city's businesses are in the hands of the gentiles. The time is now. Later may be too late.

Dear Sister, what you asked us about Itel Berzaner, She's going to America after Passover with her daughter Miriam and Diana. She's going as a tourist and what you asked about a fur coat, has to cost about 800 Lit. Moishe has a very fine little girl. We were there yesterday. Moishe said he wrote to you about everything. He wants to sell half of his brick building. His business is very bad because he is dealing with the Gentile Lithuanians.

Malkele, Raizel's daughter got married to Zalman Berke Glazer -------He bought his own truck. He died accidently. The driver pushed him against the wall and he got killed and Chaika was left a widow. It is very sad. Leiska (Eliezer) is coming home after Purim from the Army. If you are traveling to America for the Exhibit [possibly the 1939 World's Fair], try to see the machine that talks like a human being. Here they call it ageilom (golim?, meaning robot in Yiddish). We read about it in our newspaper and also about the exhibit.

Have a happy trip. Try to see our Father's brother, Velvel (Bill Krelitz)

No signature

Dear Sister Leikele, (from Rochel) No Date

How are you? You wrote and told me that you are getting used to the life there and that you got a job with Shmuel. I'm very happy you also told me that you're going to an exhibit in America and that you'll be able to see everybody. Perhaps you can tell Uncle Velvel (William Krelitz) that he should send us immigration papers. That's all we're asking him to do. We would sell everything and we could bring some money with us. I'm sure you know that my husband Gershon is not a lazy person. I talked to Moishe and Leibel while I was in Yurbrick. They told me to write to you about it. Maybe this is a place for them in Mexico but the first thing would be good if you could bring Moishe. He can't make a living here. He has a very good trade. He would do well in a big country, but not in Yurbrick. The competition is difficult here and he can't make a living here. They sold the brick building for 16,000 Lit (about $1600 - probably worth $35,000 in 1997) which Moishe could bring with him. He could go to work right away because he's got a trade.

Dear Leikele, answer right away because Moishe's situation is very bad and because, after all, he is our brother. We tried to get him a job but we were not successful. We were told that they are laying off people. He told me that he would go there with his wife and beautiful child. What else can I tell you? I'm sure you know what's going on here in Europe. It's in all the newspapers.

They arrested Moishe Eisenstadt in Smolninken. That's where he lived but he was able to escape. They also arrested Moishe the doctor and he had a nervous breakdown and they had to take him to an insane asylum. Mrs. Weinstein told this to me. I must tell you that the situation here in Lithuania is very bad. There are signs all over saying "Don't buy anything from Jews." Every stinking farmer tells us that we are only guests here and there are pogroms in many cities and that is the truth.

No signature.

Dear Leah, (from Feiga) No date (from Yurburg)

The general situation is very bad. I have a fur coat, but I haven't worn it yet. I was in Kovno (big city nearby). The outlook is not good. I'm sure that you read it in the newspapers. Let's hope that things will turn out for the best. I will answer you when I get your letter. I have a lot to tell you. I wish you the best.

Your friend,

Feiga Best regards from all your friends.

March 28, 1939 Yurburg

Dear Sister-in-law Leikele, (from Dora, Moishe's wife)

How are you? Are you having a good time? You are in a big world; it's not like in Yurbrick. Here the girls are complaining that it's very lonely. Now the situation in general is very quiet. We have a lot of refugees from Memel and Smoleninken (two nearby towns, near the German border). Leizer Peischson was in town on furlough. He was supposed to be released from the Army but they're holding the soldiers back because the situation is unstable.

The economic situation in Yurburick is very bad and all the merchants are complaining that they can't make any money. Therefore nobody spends any money. I believe that Moishe wrote to you about everything, therefore I am ending my letter. It is Erev-Passover and I did not do a thing yet. My daughter is a real mensch. She wants me to play with her. She looks beautiful. She got heavier. If the weather will be good, we will take pictures and send them to you.

Be well. Regards to your sister, brother-in-law and nephews,

Dora

No date (from Yurburg)

Leikele, (from Moishe)

Please write and tell me if the trade of a watchmaker is of value there. I know a little bit of the trade but I could learn more in a very short time. I have a guy who is a watchmaker working for me. I hired him so that I could learn the trade. I am a goldsmith and a silversmith and I know those trades well. You won't have to be ashamed of me. I already wrote you about everything. I am waiting for your answer.

Be well and have a good time.

Wishes to you, from your brother, Moishe

March 28 (Jack believes it's 1939) (from Lithuania, likely not from Yurburg)

Dear Sister Leah, (from Fanny also called Feiga)

I received your letter and I am aggravated about your plans to come back to Yurbrick. Postpone the trip temporarily. The situation in Lithuania is very bad. A war can break out any day. Germany has already invaded Austria and now Hitler is after Poland and Lithuania. You cannot imagine what we are going through. I am sure a war will break out. Wait until perhaps the Russians come in. I'm sure you'll have a better time there with your sister and spend Passover with her. What is your hurry to come back? Perhaps you can better yourself and go to America to the relatives. Make that trip. I'm sure they will give you money for the travel expenses. By doing that you will have a good time and forget your problems. When you write to me, tell me details about everything.

Your sister Fannie

The children are all, thank G-d all well

Regards from Aserlen. She asks me all the time when Aunt Leah is coming back. I'm waiting impatiently for your letter.

P.S. Everybody is buying gas masks for Passover

March 27, 1939 April 12, 1939 April 18, 1939

Dear Sister Leah, (from Rochel)

You will be surprised that I am writing to you now. Last year you send me a letter and told me that you will write and tell me everything about you and your health. Now, not waiting for your answer, I am writing to you again. My writing to you now is about the actual Jewish situation in Germany, that you already know. But now it became closer to us. Hitler already entered Memel and is frightening the Jews. Lots of Jewish people could not get out because they did not have any help from anybody. Others barely escaped and need to leave everything behind. They just took their children and ran away. In just one word, there is a big panic. Lots of refugees came to Tovrik, Yurburg and Kovno and we can not describe the sadness of the situation of these Jews. Here as you know in a small town, we know with our fingers all the poyerim (goyim) wait until Hitler will come, and then they will be against us. Mainly they have "pointed their eyes" toward the ones that are wealthy. Immediately they take the Jewish businesses. The newspapers are writing that the future of our Jewish people will be tragic in a very short time. Hitler will establish a decree against Jews in Lithuania, that now the panhandle is in their hands (that means he made an ultimatum to Lithuania). You now can imagine how Lithuania is "standing over hen foot" (a Yiddish proverb which means is trembling). In just one word, dearest sister and brother-in-law, the only thing we just want is to be SAVED and that they will not take us before our time from our children. We do not want our children to be orphans like the German children. I do not need to describe you in detail what's happening here. You already know the same news from the newspapers. My request to you is that you send us papers as soon as possible to be able to get out of here. About money, you do not need to worry, now there is still time to sell our businesses. Now we can also obtain a loan from our house. Yes, it is really sorrowful that we must give away our businesses so well established and having taken so much work and with a such a good name, but what can we do, the only thing that we want is just to be SAVED FROM DEATH. See my dearest and hurry and do everything possible to try to save us and take us out from the jaws of the lions. My oldest son Yosele says to me, "Mama, write to aunt Leyken a letter and she will save us from death. She knows us so well." There is such sadness from the kids when they listen to the predictions of what will happen. We all have intense feelings of fear and anger because we know that the death is waiting for us. And what can be worse than suffering alive? They are being cruel. IN JUST ONE WORD SAVE US AND HAVE PITY FOR US AND FOR OUR CHILDREN. See urgently what can you do and answer us as soon as possible, because we want to know if we should ask for a loan on our house. I finish my writing to you.

Be well. Your loving sister, sister-in-law and aunt Rochel

Gershon and the children send regards to all of you. I anxiously await your immediately answer with good and happy news.

Just a few words about today news: Please you must urgently get us papers, we do not care if they will be either for the city or another place.

Dear Sister Leike: See to it that they will send us papers as soon as possible. Leike: Please write to me. Do not wait to receive a letter from us.

Be well and regards from your sister

Rochel

Answer right away when you receive our letter.

No date

Dear Leikele, (from Rochel?)

When you go with your friend to America, write and tell us right away. A lot of people are leaving Kovno.

There are now refugees here from Smolininken and Memel. Dear Leikele, imagine what we have to do, we had to make a collection for them. They came without anything. Everything was taken from them. You should see the condition that Shlame came in with her children. It a good thing that she has a few Lits. Yisrael eats at our house. They are in a pitiful situation.

All the rich people in Yurbrick are sitting and eating because they have the money. Those who don't have anything, get help from public aid. How long that will last, nobody knows. In the meantime things are not good. We would borrow but nobody has any money.

Dear Leikele, tell us how you are and how you spend your time. Also tell us about your friend, and do you think you'll get marrried soon. Beile's mother asked us the same thing. Feige and Yakov send their regards. Feige looks very well. Leibel and Rochel came to visit us, and they also went to Shauvel.

Best regards and kisses to everybody,

Yours, Rochel (?) Please answer.

No date (- but after 1940) (Probably from Rochel, or maybe Fanny - Feige)

Dear Sister Leah,

How are you? How is your health? How do you keep busy? Write a few words. My only wish is to see you. Regards to dearest Beila and I wish her all the best. She should get a good man, who is a good-hearted person. I am ending my letter and hope that I get a speedy answer from you. Save us from Hell. Make out papers for us because if you don't do it now, later will be too late. We hope you will be able to do.

I'm thanking you in advance. I'm sure I don't have to tell you the rest you know yourself. Best regards from my husband and children. Have a happy Passover. It will be a sad Passover for us because we live in a dark world. We want to be rescued otherwise we'll go under. Leah, I hope you'll be a good mother to your son.

March 25, (1941) (date not clear)

Dear Sister (from Feiga)

My letter would have been in you hands but I neglected to send it to you. I did not get a chance to see your son's picture. You should raise him in good health. Hope you'll be very proud of him. If it isn't too hard, write us a longer letter. Rochel received a letter. She's getting rid of everything.

Be well. Kiss your son from everybody. Our Esther is learning to write and so will be writing a letter to you. After Passover she will go to school.

This was the last letter received. On June 22, 1941 the Nazis invaded Lithuania, and Yurburg was one of the first towns overrun because it was across the Nieman River from Prussia. Within three months, all the Jews of Yurburg were murdered.

The small town of Sudarg is known to have come to existence during the second half of the sixteenth century. The quiet sleepy Lithuanian town can be found in the southwest of Lithuania, on the left bank of the Nieman River about 5.4 miles down-river from Yurburg.

The town of Sudarg, with its earthly scent of the forest, drawn out green pastures sprinkled with yellow dandelions in summer, with grasshoppers spinning around and sparrows joining in to sing the tune of other living creatures, is a town where peace seems to be the very essence of existence. But, like other Lithuanian towns, it hides a dark history of our past.

History books tell us that Jews began to settle in Sudarg at the end of the eighteenth or at the beginning of the nineteenth century. In 1923, there was a small Jewish community of about 273 people living peacefully in the quiet boroughs of the town. Jews ran a few bakeries, grocery stores, two taverns, and a pharmacy and had their own two Jewish tailors and a butcher.

My father told me that the Jews of Sudarg also had their own synagogue called "Di Shul", decorated inside with spectacular wood engravings. This synagogue was used for prayers in summer, while in winter people would walk to the other synagogue, the "Beth-Midrash," which was heated by a furnace.

The tightly knit community nurtured its spirit of landsmanship, and the kinship of the people helped to weather all storms in bad times.

Young Jewish people began to leave Sudarg in the twenties and thirties, mainly to Kovno or abroad, looking for a better life and bigger opportunities. Many young people from Sudarg immigrated to El Paso and Dallas, Texas and Albuquerque and other parts of New Mexico and New York City and raised families in safe countries.

My father Gershon Hilelson was born in Sudarg in 1913. He attended the "Heder", where together with other children he learned to read and write, and studied biblical scriptures and Hebrew. Later the few Jewish children of Sudarg either studied in the Lithuanian school or moved to Yurburg to attend high school, and my father went to Yurburg and stayed with relatives while attending school.

He used to tell us about the green meadows and the forests of Sudarg, the river Nieman, and about the town of Yurburg nearby. He considered himself both a Sudarger and Yurburger, and anybody who was from these two places was family. "He is a Yurburger," meant "he is my own, he is my family".

My father took my brother and me as children to Sudarg in 1961. This must have been the first time he returned to Sudarg after the war. I remember the pained, tormented look on his face as he looked at familiar streets. I remember, a local farmer recognized my father and ran towards him "Berchik has arrived! Berchik is here!" He grabbed my father's hand and shook it enthusiastically, but father looked pale and somber. I will never forget my father's voice as he kept repeating on our way back, "God, oh God, what happened to them all?"

Out of a family of nine children he would be the only survivor living in Lithuania. His mother, sister, brothers all perished in the summer of 1941, when they were rounded up and shot together with other Sudarg Jews. The whole community of Sudarg perished in one day - a destiny so similar to countless other towns of Lithuania.

After the War, the few remaining Jews of Sudarg would not go back to live in their ancestral town, and today, Sudarg is but one more vanished community. A small and forgotten town.

My father carried both the pain and the spirit of his family and his community.

I remember when I was a student at Vilnius University, my parents were trying to find a place for me stay; the university was two hours away from where we lived. The problem was solved in the spirit of the communities of Yurburg and Sudarg.

"You will stay with the Breskys" my father said. "They are family". "Who are the Breskys? How are we related?" - I asked

"It is a long story"- my father answered, "they are "kreivim," our own."

I stayed with the Breskys, who were wonderful warm people for two years, but nobody could ever explain what the relation was. It took me about 40 years to figure out the connection, and having attended our family reunion of the interconnected Naividel, Krelitz, Eliashevitz, Rosin and Feinberg families of Yurburg, in 1998, I finally understood how we were related to the Breskys:

As I was growing up, I heard the names of Naividel, Zapolsky, Abramson, Krelitz and others, but I never knew that many years later these names would evoke the same emotions in me as they did in my father these are Yurburgers, therefore they are my family.

And somewhere far away from the small towns of Sudarg and Yurburg, the spirit of these communities lives on

In Memoriam

Today I remember with love all the people in my family

who have gone to everlasting life,

and I honor the memory of the departed.

As the light of the candle I light burns pure and clear,

so may the thought of their goodness shine in my heart

and strengthen me,

and may I live out the eternal values, which keep their influence aliveThe memory of the righteous is as a blessing...

(Prayer for the Yahrzeit, from the book of Jewish Prayers)

Our plane is taking off in half an hour, and I look at the passengers checking in at the Lithuanian Airlines flight 247 leaving Amsterdam for Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital. I watch a tall slender Lithuanian woman board the plane, then a man with glasses who looks like a professor, chatting in Lithuanian to his companion. On the plane a stewardess asks me in accented English if she can help me with my carry-on luggage. I answer in Lithuanian - "aciu, thank you, I am fine".

The plane takes off and I begin to feel as if I am in Lithuania already. I hear the announcements in Lithuanian and see faces that somehow begin to look familiar. Lunch is served, and I watch a flight attendant take a back window seat as she begins to eat slowly, with an appetite and oblivious of her passengers. Suddenly I feel tense. I have a flashback and remember my Mother and how hard she worked to stock up on preserves in summer because fruits and vegetables were scarce in winter. In the early fall Father would bring home a borrowed small hand-run gadget that would shred cabbage. In about two days a barrel would be filled, sprinkled with cranberries on top, and left to ferment to a champagne-like perfection until winter, enough to last for five long months. Then there would be cans of pickles and jam preserves, the result of tedious labor. I wonder if they still do that in Lithuania.

I have a window seat next to my husband's. Our fellow passenger is a young Lithuanian coming back from the United States. He tells us he went to Florida to earn some cash. He will stay in Lithuania a few months and will go back to America where, he says, cash comes easy.

Thirty years ago I took a train from Vilnius to Vienna, via Warsaw, my first trip to the outside world. The next day I reached my destination - Tel Aviv where I would stay for six years before moving to Canada.

The plane begins to descend. Through the window I see small neat squares of luscious green fields, valleys and hills. The land below looks rich and fertile.

We take a cab to the hotel where we are about to meet our group - eleven other travelers, Shtetel Shleppers, who are ready to travel with me through the back roads of Lithuania. Though we are not closely related, our roots can be traced back to one big family in Yurberik. I am the only one who has lived in Lithuania and speaks the language

We meet our group in the lobby of the hotel. I look forward to spending some time with the people in the group and getting to know them - Esther and Brenda, Gary and Mark, and our family-encyclopedia-wizard Joel, and all the others who came with us.

We also have a tour guide Chaim Bargman who looks like a character found in the books of Sholom Aleikhem, Bashevis Singer or Babel. He could be Tevie der Milhiker, or Curly of the Three Stooges. Or may be even a defiant Trotsky? In my head Chaim does not quite fit the image of a smooth-talking and well-groomed tour guide. I ignore his funny accent and faulty grammar, and forgive him the spots on his windbreaker and baseball cap, the two inseparable accessories in his attire. For, above all, Chaim looks to me like he is a Jew with a mission. His baseball cap has two embroidered words in Hebrew - "Moreh Derekh", Teacher of the Way.

The next morning we are on our tour bus in Vilnius. I take the window seat and look at the streets that once were familiar. I don't recognize where I am. Then it dawns on me - this is Basanaviciaus street. My friend Genya used to live here, this is where we walked after classes at the University.

Suddenly sadness engulfs me. I realize I will not find anybody I used to know. A town without the people who once lived here is like a town without a name. I remember the faces I used to see on these streets and recognize in a crowd. Without the people who were part of it, it is a strange place, like the one I never visited. Years have gone by, and we have all left. Childhood friends, relatives are now scattered all over the world.

Unlike the generation before us, we left in time, and built new lives. Why then do I still feel so sad?

We go to Subaciaus street, and I see a few blocks of apartment buildings. This time I recognize the place. This is where the Goldsteins used to live. Chaim, our tour guide, explains that before the war this was the Baron de Hirsh Housing Project converted to a Jewish prison camp by the Germans during the War. I am flabbergasted by the discovery that I never knew that this apartment complex on Subaciaus street was a Jewish prison camp.

Behind the apartment building, in the middle of a small square we find a monument. We light a candle and say the words of Kaddish for those who perished in this camp.

Chaim Bargman, "Guide of the Way" in the Lithuanian Park in May 2001. Palace of the Russian Prince is in background. Photo not in original Yizkor book - Photo courtesy of Dr. Leon Menzer.

Our next visit is the old city. We go to the Vilnius State University and enter old and damp hallways of my Alma Mater. Posters at the entrance and the narrow halls mark its 500th anniversary.

Slowly my memories take me back to my once carefree existence in Lithuania when I was a student. Where I was, if you wanted to fit in, you had to read the likes of Kafka, Nitche and John Updike or Sallinger's "Catcher in the Rye".

I remember poetry readings in dimly lit, smoke-filled student cafes, and evenings with bards, and guitar players, and groupies humming along to the sound of a weeping saxophone or a guitar until the wee hours of the morning. If you had seven kopecs to pay for black coffee, you were in for a treat. Sipping bitter coffee in between chains of cool Bulgarian BT cigarettes, you could engage into endless discussions on the purpose of existence and the meaning of life, and chat with bohemian dissidents who frequented the cafes. To add a simple sophistication and an air of nonchalance, you would don a beret pulled to one side, or would puff imported cigarettes with long filters. There was nothing to compete for with other students, and the only rat race you could find was "who managed to get hold of the latest issue of Solzhenitzin's book published by Samizdat?" Those were simple times filled with dreams of a future in distant lands.

Back in the hallways of my Alma Mater, I stop to skip through dozens of announcements on the billboards and come across a curious notice about a program offered by the school. The program is called "Stateless Cultures", and it includes studies of the Yiddish language. A visiting American Professor Dovid Katz teaches the course. This truly amazes me. Yiddish was never permitted in any educational institutions in the Soviet Union. It is now a disappearing language, and I hold on to the idiomatic, expressive vernacular I still remember.

We walk outside and go to a narrow street just behind the small University campus. This was the street once called "Jewish", and it was home to many families. The street had a different name when I lived here. Today it got back its original name. I am puzzled and I try to figure out, why I did not know any of this when I lived here. And why didn't anybody tell me that during the war the Jewish Ghetto of Vilnius was just around the corner?

Only at the end of the trip I would find my answers to all these questions that kept haunting me all through this trip.

Religious affiliation is no longer forbidden in Lithuania, and there is a dwindling Jewish Community in the city. Out of a community of 120,000 before the war, only 3,000 Jews remain in Vilnius today. Many of the families are not of Lithuanian descent, having moved here in the last few years from Russia, where life is still tough.

The Lithuanian Capital now boasts a Jewish Community Center. Our next stop is there.

We enter a shabby building carrying architectural remains of Stalin's

epoch with its signs of exuberance - high ceilings, big windows and

large rooms. The Director of the Community Center, Mr. Levinson

greets us. I recognize him; he is the father of Natasha, an old

friend of mine, now living in Toronto. I am afraid he will think I am

a ghost, but I approach him asking in Russian:

"Mr. Levinson, do you remember me? I used to live around the corner, remember me?

He looks at me and says - "I am so sorry, dear, did you really? I can't remember, I am an old guy".

I tell him I occasionally speak to his daughter in Toronto. Levinson warms up and shakes his head. "So many years went by."

We walk into another hall where walls are decorated with hundreds of photographs. These are photographs of Jewish soldiers who fought the Germans in the 16th Lithuanian Division. I remember my father used to say that the 16th Lithuanian Division should have been called "the Lithuanian-Jewish Division". The hyphenated semantics presented no interest to me at that time. I was more interested in D. Lawrence's "Lady Chaterleys Lover" and the Voice of America on my short-wave radio. I would only come to understand the importance of these semantics to War Veterans later in my life.

My father's photograph is not there. He and his brother Leib were soldiers serving in the 16th Division. Leib lost his life in 1943. I think the Jewish Community just did not have Leib's photograph because he perished early in the war. What about my father's photograph?

Chaim tells me I should send my father's photograph to the Jewish Community Center of Lithuania when I return home to Canada. I remember that we had one remaining small passport-size picture of Leib with an inscription in tiny Yiddish letters on the back of the photograph. I make a note to send the photographs of both my father and Leib to be put up on this wall.

On an adjacent wall there is a huge plaque with many names. That's the list of fallen soldiers. I read through hundreds of names carefully inscribed in alphabetical order, with a date next to each name. I get to the letter "H" and I read, "Leib Hilelson, Killed in Action, 1943, Battle near Oryol". I read the name over and over again, and touch the engraved letters with the tip of my fingers. This is Leib, my father's brother? Though Leib's photograph is missing, his name is here. I feel a lump in my throat. For the first time, I actually see a place where the memory of Leib Hilelson can be honored. He never even had a burial place. I feel so grateful to have found his name on this memorial wall, one among hundreds of other names.

Then, I think of all the other relatives we lost - uncles, aunts, cousins, grandmothers and grandfathers. We have to find the places where we can light a candle and say Kaddish for them - something I never did when I lived in Lithuania.

Throughout our 10-day journey through the back roads of Lithuania we found these places where white monuments would mark common graves and memorial plaques would state numbers, not names. The inscriptions would often be in the Hebrew of Yiddish languages seemingly undergoing a late revival in this part of the world.

We found many small towns that once hosted vibrant Jewish communities where nothing but old Jewish cemeteries remained, overgrown with impenetrable thick weeds, and broken gravestones and even those could disappear overnight.

Chaim knew of all the 250 Jewish mass massacre sites in Lithuania and the history of every small town where Jews lived. All of Lithuania was Chaim's backyard. A keeper of the collective memory of Lithuanian Jews and a scholar in his own right, Chaim was eager to impart his knowledge to anybody who would listen. He told us many heroic and tragic stories my generation hardly ever knew, although our history books were filled with dates and battles the glorious Soviet Army won in World War II.

Chaim's stories were from the era where stories would never end, and today many people are going back to Lithuania to hear and find out more.

Sometimes I would wonder - if Chaim, who knew of all these forgotten places, if he left Lithuania tomorrow, who would know where to find these cemeteries and mass murder sites? Who will preserve the memory of our lost relatives and who will guard their resting places?

The poignancy of those moments would often overcome me, as I would remember that Lithuania was like hundreds of other places in Europe where Jewish Communities once lived and then vanished. My generation, actually, helped this happen by choosing to leave. Should it not be up to us to preserve the memory of what now seems to be our ephemeral past?

Like other countries, Lithuania today, is just one big and sad museum, a showcase of a vanished culture, which so greatly enriched us. This culture left its lasting imprint on us, the Jews, called "Litvaks."

I carry it with me, this special sense of Yiddishkeit, the Lithuanian kind. When I came back to revisit that part of my identity and find its roots, I did not find it Lithuania.

I found it in me instead.

Ponar looks like a country place in the outskirts of Vilnius. We leave our bus and walk through the densely wooded area with winding pathways. We hear the wind as it softly runs through summer leaves barely touching them. Birds are twirling and chirping above in their summer dance, and ever so friendly. There is a soft smell of pine and cedar trees. It is serene and peaceful.

We walk to the small Museum of Ponar. We find a Lithuanian employee inside. He shows us a map where arrows point to geographic locations of Shtetls where Jews once lived. The arrows, actually, mark places where large numbers of Jews were killed.

I find Yurberik on the map, then skip through a dozen of other shtetls I come across a town called Solok in the East of Lithuania. That is my mother's shtetl. When we lived in Lithuania, I remember, my mother would make an annual trip to Solok in summer on Memorial Day. But she would never take me, or my brother along. Not even one photograph of her family could be found after the war. I have never seen a picture of my grandmother from Solok. When I was a child I would imagine my smiling grandmother I have never met, with gray hair, kind blue eyes and an apron. She would softly pat me on my cheek and tell my brother and me the wonderful tales of her past .

Chaim tells us the story of Ponar, and, as I look at the winding paths, this place begins to look somber and ominous. I remember lyrics from a Jewish Ghetto song "Never say you walk the road of no return". Prisoners sang that song as they walked these paths and never returned...

Ponar is the place where all hell broke loose in 1943. It was the killing ground of Jews from Lithuania, Poland and Germany. From the Ghettos and Labor Camps Jews were transported here to be killed in the thousands. They were made to dig their own graves, stripped naked and shot into the freshly dug pits.