-

With much debt to and reliance on Susan Wynne's book for the first part of this research.

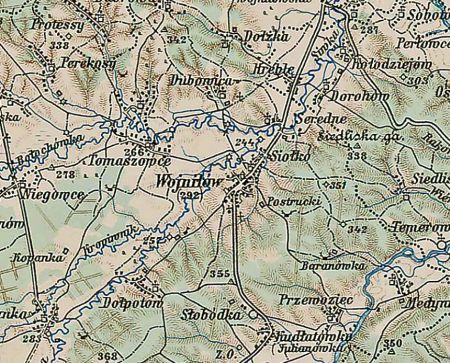

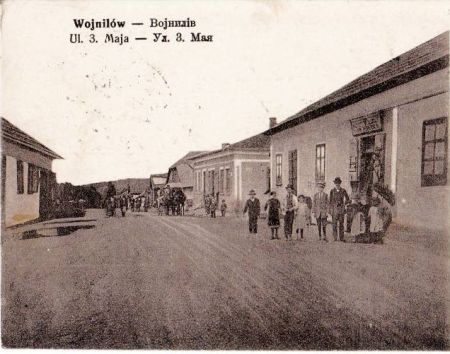

Wojnilow dates back to the mid-16th century when it was granted Magdeburg (city) rights. The earliest known Jewish community here was in the 18th century. Jews received the rights of living in the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1867 and Galicia remained part of the empire up until World War 1. Wojnilow was a shtetl in the district of Kalusz, in the province of Stanislawow. The Jewish population reached 1,115 in 1900 out of a total population of 2,726. It is where my grandfather Samuel Drach was born in 1884. However, after the Austrian Empire collapsed at the start of World War 1, the town became part of Poland and then, in 1939, when Germany invaded Poland, the Soviet Union declared the Polish state dead and the town passed to what is now Ukraine, and its modern name is Voynilov.

As was the case elsewhere in Galicia, Jews began migrating to the region in the eleventh and twelfth centuries from Germany. After the Tatar invasion of 1241, they began to arrive in large numbers and were welcomed by Polish kings who were anxious to rebuild devasted urban areas of the country, according to Paul Robert Magocsi's book on Galicia. Magocsi writes that Boleslaw V the Pious (also known as Boleslaw the Chaste) placed them under his protection and defended them as a group whose main business was money-lending.

One of the first rabbis in the town that became Wojnilow was Aharon Siegel, who was a rabbinical judge in 1673.(Later rabbis in the town's history included Shmuel-Nachum bar Kahat Gassenboyer in 1835, who was succeeded by his son, Menham-Yisrael Gassenboyer, who died in 1894. Yitzhak-Zvi bar Menahem-Yisrael became rabbi in 1894 and held the position until the Holocaust.

The town was said to have begun as a private possession of the aristocracy and was known as Prokopov, after its owner, Prokopi Sieniawski. Jews in the town during the mid-1700s were required by the owner to contribute towards the construction of an Armenian church. Jews suffered harassment from Armenians who saw them as competitors. By the end of the century, the Jewish community had become organized.

The first records in the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People in Jerusalem date back to 1778 where a summary of town revenues was noted.

The incorporation of Galicia into the Austrian Empire in 1772 represented the high point of Jewish life in Galicia. From 144,200 people in 1776, the Jewish population grew to 871,895 by 1910.

The period from 1869 to 1900 was considered a “Golden Age” for Jews living there, according to historian Suzan Wynne. In 1869, the Emperor Franz Josef emancipated the Galician Jews, the last in the Austrian-Hungarian empire to be granted that status.

“Franz Josef was widely considered a benevolent ruler by his Jewish subjects…Many Jewish families with roots in Galicia relate romanticized stories about Franz Josef hunting in nearby woods and visiting their towns and, even, homes and synagogues,” Wynne writes. “With increased access to education, Jews and others in the society who aspired to a better life were able to take advantage of new opportunities in Galicia and other parts of the empire. Although most people continued to be very poor, their sense of hope is evident in the literature that was written in that period.”

Here is a short description of life in Wojnilow in 1910, six years after my grandfather left it, as told by a Jacob Eisenberg to a relative, Jonathan Eisenberg.

His father had a bath house in Voynilov. Women went Friday night for a bath. Men went Friday night to schwitz. It was across the street from his father's house. The baba ran the bath house. Windows were broken and the wind came in. They made a hot fire and threw water on the stones to make steam. One side of the bath was cold water, the other side was hot. They heated with wood. In the bath house was a michvah. They polished their boots and left them in the house, ran across the street to the bath house in their bare feet even in the snow. They charged two groshen to take a bath. You bought wood and besom (small switches) for the sauna. The wood measured 36" to put in the big oven. Big stones got red hot.His family had a cow and their own chickens. They fed a goose to have fat for holidays and shabbas. They made butter and butter milk. On Friday, they made bread for a week. They rubbed the bread with garlic and put it on the stove and toasted it a little. They had a garden. They grew potatoes, corn and zibila. They had berry bushes and grew prunes, peaches and apples. They had enough to eat. The best fresh eggs, cheese and bread. They had a wood stove. They made their own matzos. They made matzos for the neighbors, too. He had to work four or five weeks before Passover, sometimes six weeks, to make matzos for the neighbors. He started work about 5 a.m. They had 12 girls who worked for them. They rolled the matzos out flat and used a redel (wheel) from a clock to make the lines. In the old country, he made coats from lamb. They wore the fur inside. He also made hats. If you were a big man in temple, you had a fur hat and a cane.

Some people had skis made from wood. Others had sleds used on the hill. One Saturday at 10:00 a.m., there was a mobilization. They blew trumpets to call up the reserves. Everyone was in the reserve up to a certain age. Even his father-in-law, who was an old man, was taken into the army too, to clean floors. Jacob served in the Austrian Army, three years in the infantry in the town of Stryj, then six months in the cavalry in the town of Pshemis.

However, the good years in Wojnilow did not last.

After 1900, political and Catholic leaders in Galicia pushed for more power. Wynne writes that this “strengthened the influence of those with strong anti-Jewish feelings among the lay and Catholic leaders in Galicia, and diminished the degree to which the central Austrian government could provide protection to Galician Jews.

There had been a few small-scale pogroms in Galicia during the period of 1880-1900, but the number and intensity of these pogroms increased after 1900, as Catholic priests encouraged their parishioners to strike out against Jews in both violent and economic ways. Most damaging were the organized economic boycotts of Jewish businesses and agri¬cultural products, as well as formal legislation generated by the Galician Diet, which outlawed Jewish involvement in any aspect of the production or sale of alcoholic beverages.”

During the period of 1904-06, the Jewish community in Wojnilow complained to authorities about religious taxes and corruption, according to an index of records at the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People.

The worsening conditions were compounded by the extent of poverty and backwardness in Galicia, as well as high rates of disease and death. There were typhus and cholera outbreaks in 1866, 1873, 1884 and 1892. During one of those outbreaks, a Catholic priest named Zygmunt Gorazdowski,who was ordained in 1871 and whose parish included Wojnilow, was later recognized for his efforts to help the sick and dying despite risk to himself when he was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI in 2005.

The result was that between 1881 and 1910, an estimated 236,000 Jews left Galicia. (Wynne says the Jewish population of Galicia ranged from 686,596 in 1880 to 811,103 in 1910, about 11% of the population. Magocsi had put the figure closer to 900,000). Galician Jews began coming to the U.S. in the 1880s, with most of them settling in a small area of the Lower East Side, establishing synagogues and landsmanschaftn, or social welfare organizations. Magocsi writes that "encouraged by steamship agents who visited the Galician countryside, the first emigrants (non-Jews as well as Jews) began to depart in 1880. Having heard about the success of their brethren through avidly read letters, others established a pattern of chain migration that reached large-scale proportions during the first decade of the twentieth century."

The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust puts the Jewish population of Wojnilow in 1900 at 1,115 out of a total population of 2,726.

In 1919, there were a series of pogroms in the Ukraine, said to be carried out by groups associated with the Ukrainian nationalist military leader Symon Petlura, at a time when Wojnilow was in a region under the rule of the reborn Polish state. Jozef Pilsudski, Poland's head of state, had signed a military agreement with Petlura in hopes of holding off the Red Army when Russian leader Vladimir Lenin launched the Russo-Polish War of 1919-1920. Petlura's complicity in the pogroms has been a matter of debate among historians, some arguing that he did not do enough to stop them because he did not want to alienate his base of support and others asserting that he did, in fact, actively seek to halt anti-Jewish violence on a number of occasions.

A group describing itself as the Jewish Relief Committee at Wojnilow wrote to the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee on November 18, 1920 with an account of the devastating effect of the pogroms in Wojnilow and pleading for assistance in dealing with the aftermath.

The committee said that the "Army of Petlura" had struck in the town in late August and early September leaving the Jewish population "robbed and ruined" with "legions of orphans, widows, cripples and wounded (remaining) with roof and without even the possibility of earning a livelihood." Its letter to the Joint Distribution Committee continued:

On Friday, August 20th, the excesses began. At midnight several cosacks (sp.) rushed into the house of the most wealthy Jew, Mr. Mendel Herschberg, and without listening to his prayers and promises of giving them his whole fortune, cut off his ears and smashed his head with swords. This was only the beginning...It is difficult to relate the dreadful scenes which took place in the next days. It was a real hell, and these pictures will forever remain in our minds. Among the victims were...Munio Hahn, writer at a notary, who has been killed in a bestial manner by a stroke of the sword on the head; Leiser Andacht, tenant of a farm at Temerowiex, who has been first hanged and afterwards cut to pieces by the cosacks; A.M. Fledermause, a needy shop-keeper who has been shot through the head; a most needy shoemaker, Eber Laznik, to whom the Cosacks had cut off one hand, in consequence of which he died shortly afterwards...

The local committee estimated that five Jews were killed or died from wounds, 14 were "dangerously" wounded or mutilated, 48 others were wounded, three women were widowed,14 children were orphaned,and 23 women were "dishonoured" or raped.

There are records from the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People of anti-Jewish actions in Wojnilow by Ukrainian nationalists in 1936-37.

The extermination of the Jews in the Stanislawow province, that included both towns, was carried out under the command of an SS Captain named Hans Krueger, (the “SS” being the Schutzstaffel or the arm of the Third Reich that led the mass murders.) Over 16 months between 1941 and 1943, Krueger, with a small squad of men sometimes numbering as few as 25, organized and implemented the shooting of some 70,000 Jews and the deportation of another 12,000 to death camps in this part of Galicia.

To increase his personnel, Krueger built up a unit of Rumanian and Hungarian ethnic Germans sworn to the Security Police. He also drew on a contingent of municipal police known as the Orpo, who were dispatched to him from Vienna. In October, 1941, Krueger carried out “Bloody Sunday” in the town of Stanislawow. The Jews were driven from their homes in one neighborhood of Stanislawow and were marched in long columns out to the Jewish cemetery at the edge of town. The nearly 20,000 Jews were herded into the large cemetery grounds, surrounded by a high wall. The victims were forced to the edge of two large pits that had been excavated there, compelled to climb onto a beam suspended over the pit, and were then shot. The executioners included Krueger himself.

The shooting continued without letup until dusk and ended, by one report, because the executioners grew tired of shooting. As night fell, Krueger called a halt to the mass murder. He had mercilessly ordered some 10-12,000 persons slaughtered. The cemetery gates were opened once again, and the survivors poured back into the city but Poles and Ukrainians had already taken over the Jews’ abandoned dwellings.

This and other atrocities marked the onset of the murder of the entire Jewish population in the Stanislawow region. The civil authorities now began to concentrate smaller Jewish communities in the respective subdistrict capital. Within a short period, the Jews who were affected were forced to relocate, trudging in large columns to the subdistrict town after having left behind their possessions.

Immediately after the Judenaktion in Stanislawow on March 31, Jews were taken from the closest smaller towns to the Stanislawow ghetto: on April 5-6, from Tlumacz, and later also from Tysmienica and my grandfather’s town of Wojnilow. The latter two towns were now judenfrei. In a private letter sent to Germany, the rural commissioner in Nadworna remarked: "Currently I'm involved in resettling my 7,000 Jews. How is something I'll have to tell you in person. It can't be explained in writing." I have seen another translation of this last line that reads: “In writing, it would not seem possible (like reality)."

All this is distant or even unknown history to the Ukrainians now living there. Roman Zakharii, an academic born in nearby Ternopil, visited the area in 2004 and sought out the Jewish cemetery in Wojnilow. Here is a link to his journal. He wrote:

I intended to find a Jewish cemetery and strange enough, not knowing myself was on the right road. I asked some older aged man nearby (who was a shepard) where is a Jewish cemetery. He was quite amazed at my question. He asked me why do I need this. I had to explain to him that I had to take photos. Definately not frequently people inquire with such questions here. He pointed me to continue walking straight the same road to the field. The small road that led to the Jewish cemetery serves as cattle road, through which shepards lead cows to the grazing fields. When I came out of the village by that road I was staggered with a beautiful open fields view. The area around is rather flat with hills on the back not higher than 100 – 200 meters I think…. . . Clearly the locals have no idea of Voynyliv Jewish past and Jewish world of Voynyliv means something close to zero for the most. I found the pile of cemetery monuments which were assembled at one point by someone, all the remaing ones with visible Hebrew inscriptions.

I photographed all with inscriptions. One was turned off with another stone, so I had to remove the upper stone to make the picture of the stone under. It was a thrilling view to see Hebrew inscriptions in such a place. It made me think when walking back of the Jewish tragedy that still continues and why it is so still? Why the cemetery is grazing land for cows, why the road to the cemetery is a cattle road and why the poisonous plant (called kropyva in Ukrainian, kropiwa in Polish) grows around the remaining grave stones, the plant that when you touch the skin gets burnt. For me it was not a coincidance, since things of such dimension both in time, place and occurance, repeating themselves from village to village can not be mere coincidences. It makes me think of God and strengthens my faith in Him and what other might call a “superstition”.

The same fate befell nearby Bukaczowce. The German Army entered Bukaczowce (also known as Bukachevtsy) on July 3, 1941. Many Jewish residents were sent to the ghetto in nearby Rohatyn. From there many were killed and buried in a mass grave in Rohatyn, while the majority were sent to the Belzec death camp. When the Soviet army liberated Bukaczowce on July 27, 1944, only about 20 Jews from Bukaczowce and the surrounding towns had survived those who hid in the woods, those who found shelter with Christian neighbors, and those who had false papers. A good number of Bukaczowce's Jews survived by escaping to the Soviet Union. (At its peak, there had been about 1,216 Jews living in the town in 1900).

Copyright © 2009 Bruce Drake