|

Švėkšna,

Lithuania

|

Press Family

By Doctor Shirley Press, e-mail: SPress0602@aol.com

For my father’s history,

I had to rely on documents from the ITS, the United States Holocaust

Memorial Museum, and HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society.) I also interviewed

family and friends. According to ITS records, Gershon Press was born on June

14, 1918, in the Lithuanian town of Kovno. There are no records of my

father’s parents Beines and Sonja (nee Cohn) or his younger brothers Beryl,

and twins Meyer and Welrel. The only recollection I have of my grandfather

that my father told us was that he had been drafted into the Russian army

during World War I. My father also had told us that he was really born in

1921 and that his official records were wrong. Sam Sherron who had been a

childhood friend of my father’s brother Beryl confirmed this. Sam had also

been in the Kovno ghetto with my father. They were reunited at the Feldafing

DP (displaced persons) camp in 1945 after both had been in concentration

camps. Afterward, they found each other again in America and grew close.

When I interviewed Sam in 2010 at age 84, he specifically remembered that my

father had been five years older than him. Despite the horrors of the

Holocaust, Sam insisted that my father survived to live the life of "a happy

person.”

Another person who knows

about my father’s past and remembers him very well is our former neighbor,

Jim Serchia – the one who gave us kids nickels and dimes for answering his

current affairs questions correctly. He and my dad were best friends. Jim

said that Gershon had to shoulder a lot of family responsibility after his

father died early from a stroke.

“He had to become the

breadwinner,” Jim said.

Another fact Jim recalled was that sometime during my father’s early

childhood his family moved to Sveksna, Lithuania, not far from the Baltic

Sea. The earliest documentation of this town is in the 14th century

according to Sveksna: Our Town

by Esther Herschman Rechtschafner. She wrote a Jewish history of the town

that is available online at

https://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/sveksna/.

According to Rechtschafner's research, Jews had a rich past in Sveksna. The

Jewish community dates back from at least the 17th century and was the site

of an important Yeshiva renowned for its brilliant scholars. There was also

plenty of anti-Semitism, which lasted well into the 20th century. As late as

the mid-1930s, a rabbi was accused of killing a Christian boy to use his

blood to make matzoh.

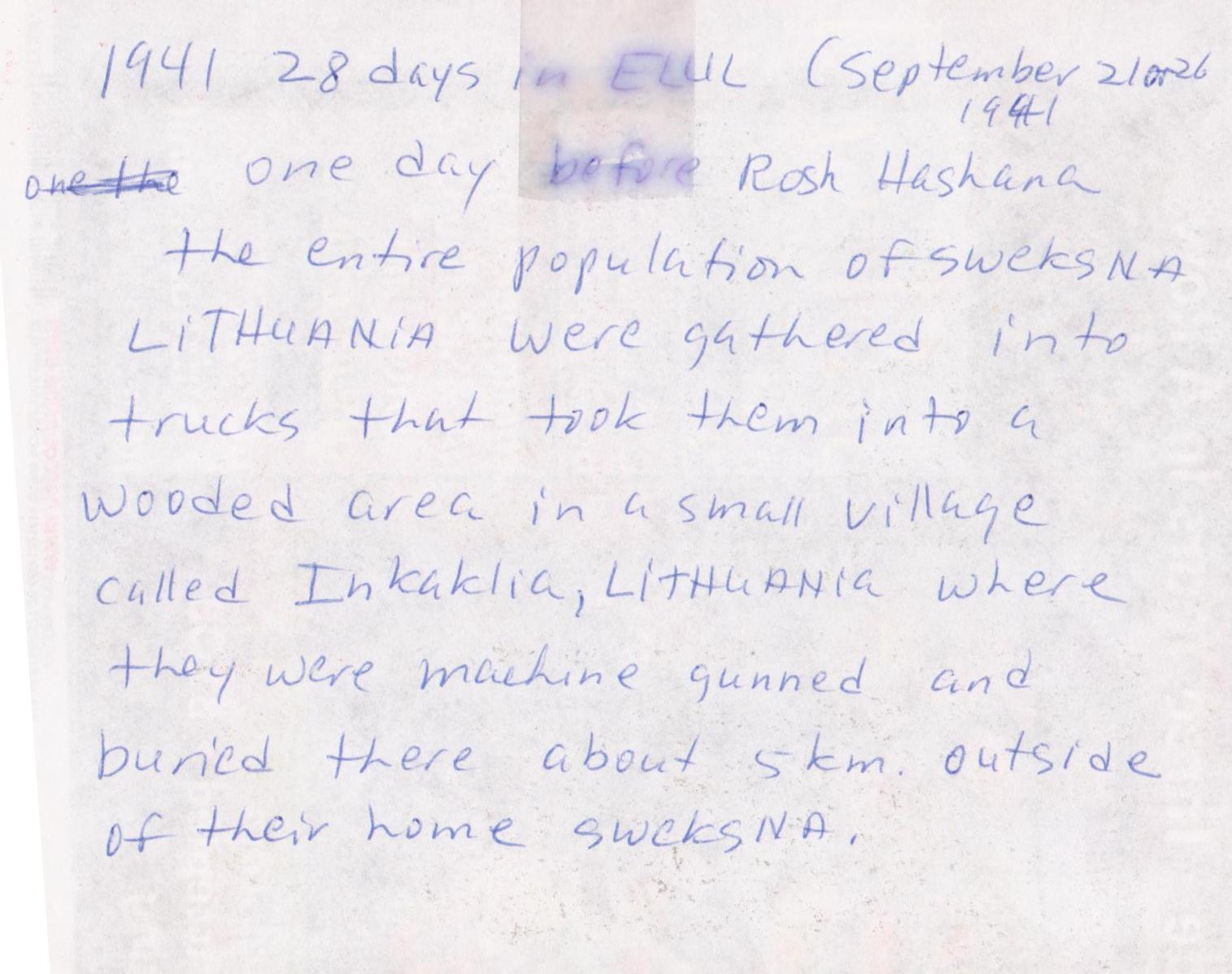

At the time of the 1941

German invasion, my father was living and working in Kovno, which is not far

from Sveksna. His job was shearing the skin off cattle and curing it into

shoe leather. His mother and younger brothers had stayed behind in Sveksna.

The Nazis captured them and murdered them with machine guns, part of the

Germans' large-scale immediate slaughter of the Jews. They were buried in

ditches in a mass grave in Inkakliai, Lithuania, in September of 1941.

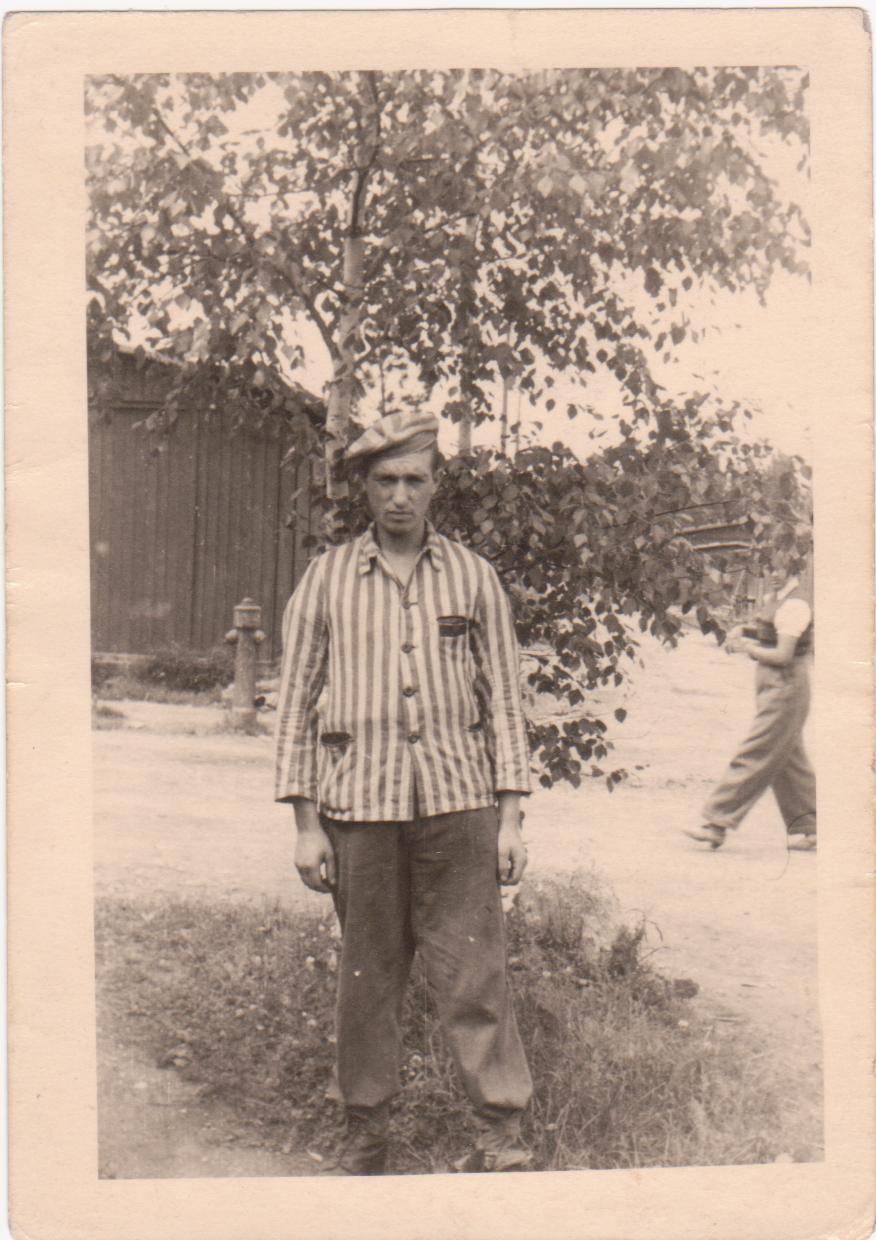

My father was arrested on August 15, 1941, at the

age of 20, and was confined in Kovno's ghetto where he endured forced labor.

In 1943, it was converted to the Kovno concentration camp where he became a

slave laborer. On July 29, 1944, he was transferred to Dachau concentration

camp in Germany where he was assigned the number 84847. According to the

reference book Hidden History of the

Kovno Ghetto published by the United States Holocaust Memorial

Museum, out of a total of 235,000 Jews living in Lithuania before the war,

only a few thousand survived.

My father told my sister

and me that he was a baker inside the camp making bread for the German

soldiers. As a result, he was able to hide bread for himself and his

friends. On one of his official documents, his profession was listed as

weaver. As Barb and I were growing up, we saw no evidence of either trade in

his life. He never ever cooked. He never sewed – with one exception; I

remember that my father accidently sliced off the edge of his thumb when

chopping meat in our grocery store. He calmly and without anesthetic sutured

it back together with a needle and thread. He saw a doctor the next day who

said he did a fine job. Perhaps, he really did know how to sew.

Our former neighbor and

friend Jim related this story about our father saying, “He said he was

running away from the Germans during the war and eventually got caught. He

said he was fortunate to have been assigned to a German officer and became

more or less a valet. He would do chores for him.” My father also told Jim

that he remembered the officer as being decent and that he had enough to

eat.

My father was liberated from Dachau by the United

States Army on April 29, 1945. According to ITS records, he was registered

in the DP camp known as Feldafing on October10, 1945. He also spent time in

the Landsberg DP camp, the largest such camp in Europe. In my research, I

came across Colonel Irving Heymont’s description of the camp in

Generations, the United States

Holocaust Memorial Museum’s newsletter, the Fall 2009 edition.

“The camp is filthy

beyond description. Sanitation is virtually unknown,” he wrote in September

1945. “Words fail me when I try to think of an adequate description. The

people of the camp themselves appear demoralized beyond hope of

rehabilitation. They appear to be beaten both spiritually and physically,

with no hopes or incentives for the future…” The colonel underestimated the

resolve of people like my parents and other survivors.

On May 10, 1946,

according to the passenger manifest form, my father boarded the "SS Marine

Flasher" which sailed from Bremen, Germany. The fare was $142, the

equivalent of $1693 in 2013. HIAS and my father’s Uncle Morris and Aunt Rose

assisted my father in leaving his devastated life in Europe. He landed in

New York on May 20, 1946.

His first cousin Betty

Dworkin Ettinger vividly remembers that date because her marriage to Sig

Ettinger took place one day earlier in Philadelphia. They were on their

honeymoon 90 miles north in New York City. Her father, Uncle Morris Dworkin,

knocked on her hotel room door.

“What are you doing

here?” she asked in total shock.

Click here to

view Chapter 7, recounting my father's background, from a book I have

written.

Here are photographs (click on any image for a larger view):

Web Page: Copyright © 2019 Esther (Herschman) Rechtschafner