|

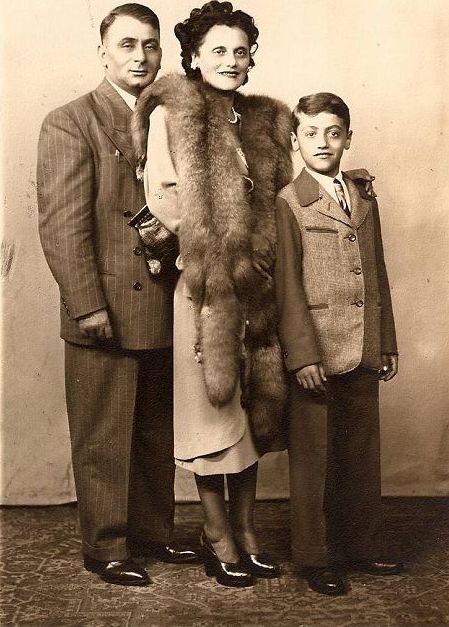

| Photo 1: The Brauner family, from upper left corner clockwise: Felix, Amalia, Adolf, Joel, Isadaore, Bertha. Circa 1930. |

As a four year old child at the start of the German occupation, I have no clear or systematic recollection of this early part of my life, almost seventy years ago. My memory is fragmentary. I can recall only isolated events, like single beads in an invisible thread of time. What I remember best are the faces of the people in the ghetto, and in our cellar hiding place, especially their look of sadness and despair.

Holocaust memoir writers often cite their obligation to bear witness as their motivation. As a young child with a limited understanding of the events, I experienced, I don't feel qualified to bear witness. Primo Levi wrote, "We the survivors are not the true witnesses. The true witnesses, those in possession of the unspeakable truth, are the (sommersu), the drowned, the dead, the (disparu) disappeared". I believe our perspective on the Holocaust must center on the victims as much as on the survivors. My main purpose in writing this memoir is to memorialize my murdered grandparents, and cousins, as well as the Jewish community of our home town. I also wish to acknowledge and memorialize our Polish saviors Kazik Starko and Roman Kalinowski

I was born in July 1937 in Stryj, a town of 35,000 people, 40 miles south of, Lvov, in southeastern Poland. My father's family was quite prosperous, owning the largest flour mill in town, as well as an apartment building, where my parents, grandparents, aunt and uncle lived in three spacious apartments. As an infant I had a wet nurse, a young Ukrainian woman, as was the custom among the more affluent families.

Stryj was in Galicia, a part of Poland that had been a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until Poland regained its independence in 1918 after World War I. The town's population was equally divided among Jews, Poles and Ukrainians. There were also small numbers of ethnic Germans and Roma. In the countryside the great majority of the farmers were Ukrainians.

My paternal grandfather, Leib Seliger was a follower of Zev Jabotinski, the founder of Revisionist Zionism, a militant nationalist movement that advocated Jewish settlement in Palestine on both sides of the Jordan River. After the ascendance of the Nazi regime in Germany in 1933, Jabotinski, a talented multilingual orator traveled throughout Europe, urging immigration to Palestine, predicting a great catastrophe for European Jews in the near future.

My father Samuel, who worked at grandfather's mill as a bookkeeper, had a combative nature. He was expelled from the gymnazjum (high school) for being involved in repeated fights with Polish students who provoked him with ant-Semitic comments. My maternal grandfather, Joel Brauner worked as a salesman for a Czech chinaware company and traveled throughout Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. My mother, Amalia, was a designer and dressmaker. She was an attractive woman with dark hair and a somber demeanor. Her three younger brothers Felix, Adolf, and Isadore, were Communists and were frequently arrested by the police, especially in late April of every year, to prevent them from marching in the yearly May Day parade.

When the war began in September 1939, Stryj, located in eastern Poland, was occupied by the Soviet army. Grandfather's mill and apartment building became the property of the state, but father was appointed the manager of the mill, and the family, while no longer wealthy was able to survive. Everything changed in early July 1941 when the Russians fled and the Germans marched into the city. The local Ukrainians greeted them as liberators and erected an arch in the main square which proclaimed "Welcome, we will line your path to Moscow with Jewish skulls."

A few months later we were moved to the poorest part of town, which was surrounded by barbed wire and barricades, and became the ghetto. My parents along with my aunt and cousin were assigned one small bedroom in a squalid apartment. My father, in order to obtain a ration card for food, was conscripted for hard labor. We had to sell or barter some of our belongings for food. Fortunately because of my father's fluency in German and Ukrainian, he was hired as an interpreter by the German officer in charge of the laborers and provided with extra food rations so we were able to stave off the starvation which many of the ghetto residents suffered.

I remember once a policeman with a German shepherd dog came to the courtyard of our house in the ghetto, foolishly tried to pet the dog only to be bitten on the face, fortunately only superficially. I've been frightened of large dogs since. I also remember a woman living next door with several small children, whose husband had been recently killed, going off with a German policeman and coming back with bread. Being only five years old, I was not aware then, what she had to do to obtain bread for her children. A peculiar event occurred in the ghetto apartment we shared with 3 other families. They held a sťance, They sat around a table and asked certain questions ; mysteriously the table leg pounded out the answer; the only question that I remember was, when would we be liberated, and the answer was 31 days.

Periodically, every few weeks there was an "aktion", a sudden roundup of the residents in the ghetto, by soldiers and police, who were then either marched to the nearby Holobotow forest, and then shot, or to the train station and loaded into freight trains which took them to the Belzec extermination camp several hundred miles away. When the action ended after a day or two, the remaining Jews were allowed to live a little while longer. Many thousands of Jews were brought by the Germans to the ghetto from the other towns, in the area, as well as some from afar. My father met an Austrian Jew, the former owner of the largest department store in Vienna, who with his Christian wife had been deported to the Stryj ghetto and was in a state of shock.. A total of 30,000 people were interred in the ghetto.

During the roundups, we were able to hide in a cellar of our apartment behind a concealed wall. My father realized that we had to escape from the ghetto to survive. He and another man, a Mr. Morgenstern contacted a Polish man named, Kazik Starko whose house was located fairly close to the ghetto. Mr. Starko's teenage son was dying of tuberculosis and the only medicine available had to be imported from abroad and was prohibitively expensive. He agreed to hide our families in exchange for payment in gold or dollars. A hiding place was constructed in the cellar of his house. Sacks of food were stored by my father and a water pump and gas lines were hooked up by Morgenstern. A few other people were informed of the location of the cellar. Mrs. Starko thought her husband was mad to risk their lives to hide Jews, and angrily left her husband to live with her mother.

In the middle of the night my cousin and I were awakened and put in a large basket under a pile of clothes, my parents, aunt, and another man, dressed as Ukrainian peasants carried the basket out of the ghetto. We passed a Ukrainian guard who fortunately was drunk and did not try to stop us, assuming we were just looters helping ourselves to clothes from the newly vacated Jewish apartments. He said in a joking voice, that where these parszywy zhidy (dirty kikes) had been sent they wouldn't need their clothes any more.

The cellar- hiding place, our bunker, housed a total of thirty five people including us. The bunker was to be our home for over two years. It was a dank long cellar room with low ceilings, dim gas lights, a sand floor, bunk beds along the walls and other beds occupying almost all the floor space. My parents, my aunt, my cousin and I slept in one low double bed, head to toe. I still remember the stale pungent odor of sweat since we could not bathe. I still see the ugly grey rats; there were dozens of them scurrying around the floor. I remember a particularly frightening rat with pink pustules all over his body. Unfortunately the rats also ate almost half of our stored sacks of food, which then had to be suspended from the ceiling to keep them away from them. Once one of the men became so enraged at them that he grabbed a club and killed one.

I vaguely remember the frequent pangs of hunger. We slept during the day and were awake at night for added security. Every 12 hours we ate some sort of broth or kasha, sometimes with bread. During the last year as food became more scarce, the portions became smaller and many people fainted from hunger. I remember my cousin Stan's sad downcast face. He hardly spoke, except to ask his mother for more food and frequently cried that he was hungry. He always slept clinging to his mother. Being two years older, he was more aware of our precarious situation, than I and was probably frightened. Once the latrine located in the corner overflowed and the stench became almost unbearable. Several men dug another deep hole and the smell subsided to its usual level.

Because of our close confinement it was agreed that the married couples would refrain from having relations. However one couple insisted on having sex and we had to endure the noise of their lovemaking. Many people angrily shouted at them repeatedly to stop but they were crude, insensitive people and refused.

I remember being taught arithmetic by one of the older boys using stones on the sand floor. I remember playing on the sand floor of a small antechamber of the cellar which was unoccupied. My cousin and I played a game with string where we would form various shapes with our fingers, a star, a spider, a mattress and transfer them back and forth. We had no other toys. I greatly enjoyed having this small space to our selves without any one else in the room, since I had no other personal space.

I remember a chimney at the center of the cellar which was our only source of ventilation as well as our conduit for food deliveries. Mr. Starko would drop a basket of food down the chimney from the roof once a week. Mr. Starko's neighbor, Roman Kalinowski met him in the street one day and surmised that he was hiding Jews because of the amount of food he was carrying home, and offered to help by also purchasing food for us to decrease suspicion on him. Mr. Kalinowski did not ask for any money but simply wanted to help.

My mother told me many years later at (age of 92) that I had told her, I wished I was a bird so I could fly outside and see the sky. When she asked me if I would leave her, I replied that I would fly back and bring back lots of food for us.

Apparently we could no longer pay Mr. Starko. The occupants of the bunker were obliged to give up any remaining valuables they had. My aunt and mother gave up their gold wedding bands, and other people gave any jewelry they had. My father and one other man then proceeded to search everyone for any valuables that might be hidden. Nothing was found initially, but the oldest person in the bunker, a childless widow in her sixties acted suspiciously and was forcibly stripped and searched. A 500 dollar American bill was extracted from her body cavity (equivalent to about 20,000 dollars today).

The incident I remember most clearly occurred some time later. We were awakened by noises of German soldiers with barking dogs only a few feet from the house. One of the neighbors had informed that there were Jews hiding there. I remember my mother and aunt weeping. Some people were praying. Several men were preparing to swallow poison and had glasses of water ready. Next we heard cries and shouts. The Germans discovered a Jewish family hiding with their children in a woodshed near the house. My mother recognized the crying voice of her former next-door neighbor and old school mate. We heard them being beaten, and tied up with barbed wire. The Germans departed without searching anymore and we were saved.

My mother told me many years later, that as she was weeping, she had a vision that her father was speaking to her, and told her that we would survive because there were 35 people in the cellar. Seven children for the 7 days of the week. Ten men for the 10 commandments and eighteen women, the Hebrew letters ?? (life). Tragically Mr. Starko was struck with shrapnel, during a bombing raid, and killed as he was dropping food down the chimney for us, the day before we were liberated by the Red army on August 8, 1944.

By this time we were all malnourished. More ominously several people were ill with typhus, including my aunt who was so weak she had to be carried out of the cellar on a stretcher. My mother's hair had turned grey prematurely during our confinement and she suffered from frequent abdominal pain. The bright summer sun was blinding after more than 2 years in the cellar. One of the Russian soldiers gave us blankets, because our clothes had rotted in the dampness of the cellar and were in tatters. My mother sewed my cousin and I pants and jackets from these heavy army blankets.

Only about 300 Jewish people had survived of a total population of 30,000. We were informed by several survivors that my grandparents Leib, and Leah Seliger and Joel and Bertha Brauner were murdered in September 1942. Apparently they were crammed into the cattle cars so tightly that they died during the journey to the Belzec extermination camp. More than 20 of my parents' aunts, uncles, and cousins also perished. Unfortunately Mr. Starko's son succumbed to his tuberculosis a few months later. The two oldest of the seven children in the bunker also died tragically. Helenka age 16 at liberation was consumed with hate and wanted revenge. She joined a group of partisans fighting in a nearby forest, and was killed, Dov, about 14, was emotionally destroyed by his experience. He had missed 5 years of school and could not make them up. He immigrated with his parents to Toronto, Canada after the war, became addicted to drugs and alcohol and died of a drug overdose several years later.I started school at age 7. Since the school teachers were Russians not Poles I had to learn the Cyrillic alphabet, and was also indoctrinated about the great achievements of Communism and our great leader Joseph Stalin. One day our teacher took us to the town square, where a gallows had been erected. Six Ukrainian Nazi collaborators had been captured by the Russians and were hanged while we watched. I remember one of these men was tall and gaunt with an amputated leg. My mother was quite upset at the school, but could not complain for fear of reprisal by the Communist authorities.

In May 1945 the war finally ended. My father invited several Soviet soldiers to our home to celebrate. They brought several bottles of vodka. One officer gave me a glass of vodka, and remarked that since I was almost eight years old, I was old enough to drink and toast our glorious leader Joseph Stalin and the great victory over the fascist Germans. My mother grabbed the glass away, much to his dismay.

The Soviet Union annexed eastern Poland after the war. We moved to Bytom a town in western Poland, near the German border to escape the Soviets. All the surviving Jews left Stryj as well. I attended the local Polish public school, but was repeatedly taunted and called dirty Jew by the other students. A few months later, my father received a letter from a Polish partisan organization, threatening death to the Jew Seliger. We fled to a displaced persons camp near Munich, Germany called Feldafing which had been organized by the American occupying army to shelter Jewish survivors. Approximately 1,500 surviving Jews were murdered by their Polish neighbors after their liberation from the camps and hiding places between 1944 and 1946.

My father was able to contact his two cousins in New York, who sent us money for our passage and in July 1946 we traveled by train to the port of Bremen and then boarded an American troopship. We slept in narrow bunk beds, three high in a windowless chamber below the waterline, and were seasick much of the time because of the rough seas. After an 11 day voyage we arrived in New York. The next day, my father read in the Yiddish newspaper that more than 80 Jews had been murdered in Kielce, Poland on July 4 and July 5, 1946, while we were at sea.

Now more than 60 years later, I view these events with a mixture of detachment and trepidation. Sometimes when I see live rats, or when I encounter pungent body odors, I become depressed for a while. The adult survivors suffered more severe psychic scars. My mother at age 98 told me one day, that she had just had a nightmare that I was a baby and we were hiding in a closet but the Germans caught us, then she woke up.Writing this memoir has been neither a catharsis nor a measure of closure for me, since the Holocaust defies closure. My experiences have made me a pessimist. I am dismayed by the endless human capacity for unspeakable cruelty and evil, as has been repeatedly demonstrated in the six decades since the Holocaust ended, in Rwanda, Darfur, Bosnia, and elsewhere. Neither reason, nor faith is sufficient to stop us from devouring each other. I view the Holocaust as a vast black hole without hope or redemption.

Dr. Gustav Seliger |

| Photo 1: The Brauner family, from upper left corner clockwise: Felix, Amalia, Adolf, Joel, Isadaore, Bertha. Circa 1930. |

|

| Photo 2: Seliger family, circa 1932. From upper left corner, clockwise: Samuel, Yetta, Lieb, Leah. |

|

| Photo 3: Seliger family, New York, 1947: From left, Samuel, Amalia, Gustav. |