| Religious life in late 19th and early 20th century Skala was similar to that in surrounding shtetlach. Many of Skala's inhabitants were chasidish, but there were those who were not. "They believed in God," a Skala native said of his observant family. "But they didn't believe in the rebbes so much." Skala's chasids were followers of either the Chortkover or the Vishnitzer [also spelled Vizhnitzer or Viznitzer] rebbes. Each of these groups had its own kloiz or synagogue in the town. For more than 100 years, the Drimmers of Skala were rabbis for adherents of the Vishnitzer rebbe. |

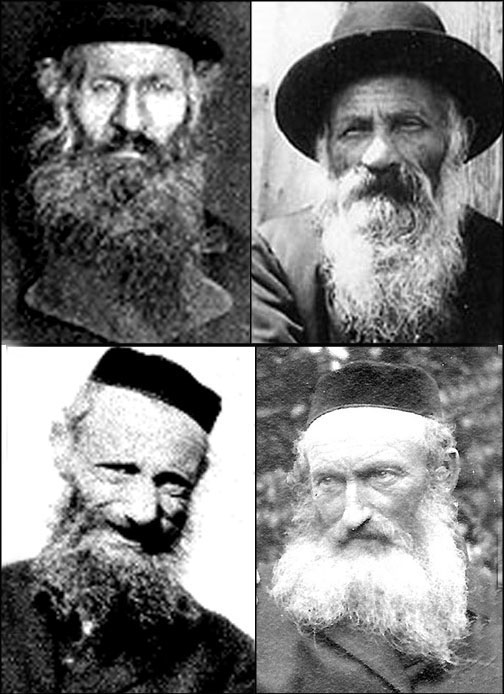

Some observant men in Skala wore the black hats of chasids, while others wore kipot. Left to right, top to bottom: Meier, Hersh Eliyah, and Zechariyah Wiesenthal; Mordkho Wolf Wasserman. |

A majority of the town's denizens were quite impoverished, but "there always was someone poorer than we were, to whom we could give charity," a former resident said. Economic circumstances sometimes required adjustments in religious observance. Unable to afford separate dishes for Pesach, many Skala residents scrubbed their everyday dishes in barrels, brought them to be toiveled (immersed) in the mikveh, then used them during the holiday.