Click on photo to enlarge

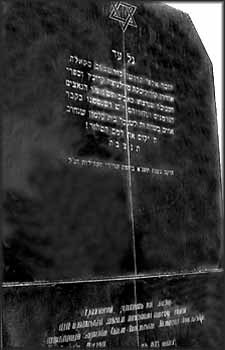

Borszczow plaque

|

There were some Jews who decided to remain in Skala, who tried to hide with the goyim, with the Ukrainians. Not too many stayed with the Ukrainians. There also were those who went into the forest. They lived in the forest in bunkers that they built themselves.

Because my brother Hersh continued to work for the Germans, we tried to see if they would allow the families of the Jews who worked for them to remain also. They had a lot of workers, not only my brother and the other Jew [Michael Yagendorf]. There were a lot of Jewish families who worked there and they continued to work there even after the pogrom. Because they still worked there, we hoped that we also would be able to stay. Finally they told us, "Okay, you can remain." They gave us permission to stay in Skala. The Ukrainian police, who were responsible for patrolling the goyim, left the Jews who worked for the Germans alone. They saw those Jews as being somewhat protected by the Germans.

The concession allowing the families to stay did not last long. In the end, they told us that despite the previous arrangement, they only would be able to keep the people who worked for them and that they would not be able to allow their families to remain.

My brother Hersh and [Michael] worked in the pig shed. The Jews were not experienced in this type of work. They worked together with an old experienced Polish worker. There also was a Ukrainian woman who worked there. Of course, there were other Ukrainians and Poles who worked there as servants, keeping the house and other things.

We didn't go to Borszczow. We decided that since Hersh was able to walk around freely in the town, because of him I also would be able to go around freely too. If I saw a Ukrainian policeman, I tried not to go near him and not to meet him. But I was not afraid of the goyim. Everyone knew that we worked for the Germans. I even was able to go to the market to buy things. So we decided that the family would stay in the town because we knew that in Borszczow the same thing certainly would happen as had happened in Skala. In Skala, since there were so few Jews, it was possible that there would not be any more pogroms. We also thought that we would have a better chance of surviving with the Ukrainians and the German border patrol.

There were other Jews in hiding and more than once I would hear shots and immediately I would run to the rooftop to see what was happening. Sometimes it would be the Ukrainian police doing searches, either because someone had informed on the Jews or because they took it upon themselves to do a search. They would kill whomever they would find.

I once ran into two policemen who were riding on bicycles. I ducked into a side street, but saw that they were coming after me, so I ran away. I came to a place where it was impossible for bicycles to enter: the policemen would have to get off their bicycles to run after me. They did run after me and I went into an abandoned Jewish house. There was one level, where the entrance was. But once inside, I saw that the outside yard was lower than this level. I didn't think about it, whether it was lower or not lower, but simply jumped from the window. It was very high up, but nothing happened to me. I got up and continued to run.

There were some Ukrainians who lived next door. After the war, they told me that they had seen me jump and they had thought to themselves: "How is it possible? How could he jump from a place like that! He certainly was either killed or maimed." They remembered that I ran away. I didn't think so much about what I was doing. I wasn't so afraid. I knew that even if they caught me, I would say that I worked for the Germans and they probably would free me. I had the feeling that if they didn't free me, the Germans themselves would free me: that Hersh would talk with one of the guards or with someone else in a position of authority. In the end, I arrived safely at the work place.

Aron caught typhus and was very sick. He was kept in bed with a high fever. Of course it was impossible to call a doctor. There were times when I was able to buy medication in the pharmacy, but I don't remember if I specifically went to buy medication when Aron was sick. During this whole period, when it was necessary I did go to the pharmacy and buy medication. The pharmacy owner was a Pole and he was friendly to the Jews. At one time, the pharmacy either had belonged to a Jew or there was a partnership with a Jew who had been taken away during the pogrom. The Pole stayed with the pharmacy and he acted very well to the Jews. If someone came to buy something, he didn't inform the authorities that he had seen a Jew.

The real danger was from the Ukrainians because they would inform on us. Those most in danger were the Jews who earlier had given their property to the Ukrainians. Many Ukrainians had come to the Jews and had suggested to them: "You see? There are robbers all around. I can watch your things. We are old acquaintances. You can leave everything with us." Many Jews made this mistake. They gave things to the Ukrainians to watch and afterwards these same Ukrainians made sure that those Jews who had given them property were taken and killed. They would inform on them.

I would go to the abandoned house and I would bring food to my family. Then I also became sick with typhus which, apparently, I had caught from Aron. My parents decided that I should stay in the house until I recuperated. I rested for one or two days until I felt better.

In these types of situations, everyone is like a stone. It is difficult to describe this. People don't think about what is going to happen to others. Everyone runs as if he is all alone.

My father ordered us to "run from here and we will meet by the house" of a certain goy. We had planned that if something were to happen, we would run to that place a little outside of the city, to the orchard of a goy whom we knew. But we would do it in a way that the goy would not see us. So we knew where to run and where we would meet. We ran in the direction of this orchard. I jumped out of the window.

This happened during the day. It was a market day. The Ukrainian policeman ran to the front door and began to shoot at us and all the people in the market place ran to see what was happening. I didn't see any of this, but someone told us afterwards.

My mother Sheindel purposely ran in a different direction and she was caught. I think it was the same Ukrainian policeman who caught her and maybe some other Ukrainians as well. She had some gold coins, Russian money that we had kept in case we needed either to buy food or otherwise to survive. Someone told us that she begged, "Take this money and let me run away before the policeman gets here!"

| My sister Edzia was shot and killed by the policeman's gunfire. My father and I managed to run away. We ran into a narrow street and from there we turned right, so that the Ukrainian policeman no longer was able to see us. We then were able to escape by running between the houses. |

My mother's fate was that the policeman killed her. We only knew this from accounts that we heard. I didn't see it and no one else in the family saw it. We didn't see the bodies of either my sister or my mother.

[Editor: According to the Skala yizkor book, "the collaborator Petryszyn" betrayed the Bretschneiders to the Ukrainian policeman Nakoniczewski, who shot Sheindel and her daughter Edzia in the market place. The yizkor book reports that Nakoniczewski also killed Aron, but that is not correct (see below). Sefer Skala, p. 54]

A while later, a Ukrainian saw him and said to him: "Look, the police are here. Get away from here." Then a German passed by. Aron recognized him as one of the Germans we worked for. This German saw my brother and stared at him. He may even have said something to him, but that was all he did before continuing on.

That evening, my brother Aron arrived at our pre-arranged meeting place in the orchard of that family of goyim. We viewed that family as more than just acquaintances: they knew our family very well and we thought that, at the least, they would not inform on us; but they had no idea that we were meeting in their orchard.

My brother Hersh arrived later, to see if any of us had survived. He and my father discussed our situation and they decided that my father and Aron should hide in one of the empty houses behind the row of houses that the Germans used. On the bottom floor of that house lived a Ukrainian boy who worked for the Germans as a coachman or taking care of the horses. Apart from this boy, the house was abandoned, so Hersh decided that he could keep the two of them in the attic and no one would suspect that they were there.

Later that night, we all went to that house and climbed up into the attic. Aron and my father Avraham stayed there. Even though I had recovered quickly, Aron still was sick and it was difficult to take him to that place. Hersh and I helped him and he was able to lie there in the attic with my father. I joined Hersh at the place where he worked and we planned to bring them food. I never did go to that house. I do not even remember exactly where the place was. Hersh would go there himself, since it was close to the place where we worked.

|

The testimony of Menachem Bartel was taken in September, 1965, when he was interviewed in Tel Aviv by Miriam Tov.