RESCUE (save) A BOOK,

REVIVE A VILLAGE (shtetl)

Translated by Menahem Frenkel (Haifa)

From the first sentence I want to make it clear that the purpose that brought me to translate this book was to save it from oblivion.

Located forty kilometers from Warsaw, Serock1 had more than three thousand Jewish citizens, representing .1% of the population of that origin in Poland. Beyond natural affection you can feel for your ancestors and their roots, my interest in the little shtetl is justified on the simple fact that my father was born and raised there. Hence, everything related to his biographical data, his life and that of my grandparents and uncles, I was linked to this place emotionally even before I visited it.

Furthermore, I came to some conclusions about my personal experience that indicated to me that geography marked my story more than you could ever imagine. If my father had not left his village in time, I would not have come to this world and not be writing today the introduction of this book.

Those who surf the Internet (web) and enter www.serock.pl find a beautiful Polish

city located half an

---------------------------------

1To be faithful to the will of producing a Spanish version of the original book, I have adopted "Serock" to name the village and the word "srotskers" to refer to its inhabitants. Both Jews and Poles call the people "Serotsk" (hence the adjective derived), in Polish the letter "c" produces the sound "ts".

-7-

hour from Warsaw, interested in attracting foreign capital willing to invest in tourism. The spot, crossed by the wide River Narew, has on its margins clubs and country clubs where you can practice all kinds of sports and summer and weekend activities.

Among the numerous reports provided by the site, you can pick the number of people that live there today, a figure of around three thousand people. The fact is curious, since the reader will remember that this was the number of Jews living in Serock seventy years ago.

The book deals with telling the life of the Jews in this shtetl before, during and after the Second World War. And also provides relevant information on a central question: what happened to those three thousand Serock Jews. In the years I lived in Argentina I did not give this subject any particular significance, in any case, it was something that had happened in Europe, which at that time seemed very distant.

Today, April 14, 2010, I am writing the introduction to this book in Jerusalem. But what makes it possible? The book called Sefer Serock arrived in 1972 at the home of my parents in the City of Buenos Aires. They placed it in a library, beside the telephone, the calendar and telephone directories, some volumes of the Treasure of Youth, Encyclopedia Salvat and a couple of volumes of Human Anatomy of Testut I had used a few years earlier in my career when I was in medical school.

The book of Serock was blue, thick covers, heavy, with 730 yellowing pages was written in Yiddish and

-8-

Hebrew and its content was difficult for me to investigate. Inside, showed photographs of the town, in 1920 and 1930, including young people in schools, family portraits, rabbis, streets full of young girls and boys, but, honestly, by that time my mind was occupied with other avatars. I was a young doctor, single, interested in my profession as a psychiatrist and in the pleasures of life...

In the days of the military dictatorship in Argentina, I immigrated to Israel. In 1976, in Jerusalem, married with one daughter, I began to explore and rethink through my incursion into psychoanalysis and the advantage that gives the distance of the family, my relationship with my parents or, more precisely, the link to my father.

Also, during the courses I took at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Department of Holocaust Studies, the historian of the Holocaust, Prof. Yehuda Bauer, and Professor Hillel Klein, it began to emerge in me a spiritual and intellectual urgency to deepen my understanding of historical events and their psychological impact on the "Second Generation of the Holocaust", i.e., the children of survivors, of which I am part.

In my personal story, that connection was going through my father. I remember its silences, its volcanic eruptions, his pride, his pain; his eyes reflected a search for the lost beloved faces and it was the look of someone who didn't find because there is no tomb where to place a flower ... "Ich bin a yiosem"2, he said when sadness filled him.

While living in Israel I traveled to Europe, often

and for professional reasons

-----------------

2In Yiddish, "I am an orphan."

-9-

I was going to Paris, where I was headed almost compulsively, in a ritual mode, to the railway station Gare du Nord; there I stayed watching the screens with the train schedules to Warsaw. I needed to enter that silent area of twenty-two years that my father had been in Poland before immigrating to Argentina, which constituted a life lived but had not been reported or transmitted to his children.

And that theater of the mind was in Poland, Warsaw flickering on the marker boards: the platform number and time of departure or arrival. It was the '80s. I was torn between the reality of the neon sign that read Sortie a Varsovie, and a taboo, named Poiln. Poland, cursed land, tomb of the Jewish people, a place that I was forbidden to step on without my father's authorization.

In 1983, on a visit to Buenos Aires, I extended my return ticket to Tel Aviv with a ticket Madrid - Warsaw - Athens - Tel Aviv and, without communicating my decision to my immediate family, I landed in the Polish capital. There my good friends, Tito and his wife Cora Kaminker, officials of the Argentina Embassy expected my arrival. As I arrived, I was asked what were my plans."I want to go to Serock" I said.

They provided me with everything you need, a driver, a car, a translator and their home and their company.

We arrived at the village map in hand. On the trip, the translator, an official of the Embassy of Argentina, a young Polish middle class woman, informed me that she knew nothing of the genocide, nor that many many Jews existed in Poland years ago; that was not studied in Polish history in those years she added. Curious, is not it?

-10-

Since then I felt something difficult to convey a contained emotion, a need to gather traces of family history, to locate the house of my father, or sites that sometimes he was describing; find the basement where they had hidden during the First World War to protect themselves from artillery duels crossing the town. With very limited data that my father provided me over the years, I had to rebuild in place: the Market Square, the Church, the river, the road to Warsaw, neighbors. Yes, I had to find neighbors.

Luckily there we could talk with them: We were asked twenty-four hours to arrange their memories. We returned the next day. I was told about my grandparents Pan Gutkowski and Panye Gutkowska. One of those neighbors served in the Polish army with Chaim Gutkowski, my father's brother, whom he remembered with admiration, (Chaim) had been taken prisoner by the Germans and deported, he said. And then several recalled with tears in their eyes the expulsion of the Jews from the town.

In our farewell, they also presented to me, visibly moved, a ritual cup found in one of the neighboring houses where Jews had lived. That ritual cup is now in Jerusalem when we make the blessing of wine at dinner every Shabbat and Jewish holiday.

Already hard at work translating the Book of Serock, I began to make a cut of content and translate into Spanish those chapters echoing in me deeper.

Readers may wonder why I decided to make the Spanish version of the Book of Serock ... The reason is that between the years 1925-1937 most of the natives of this small town emigrated to Argentina

-11-

Jakubczak Slawomir

Mss. Slazka and Konopka in the Market Square. Year 1939.

and, as the United States was closed to emigration, a smaller amount came to Israel during the British Mandate. The importance of this translation is that the readers of Argentina or South America could not read the original text. Now they have access to much of its content. Actually, I'm not a professional translator, but I felt called to channel this book, originally written in Yiddish and Hebrew, to my native language. This task made me think about the act of translation. Maybe what I mean is that you not only transform the text from one language to another, but the same person who made the

-12-

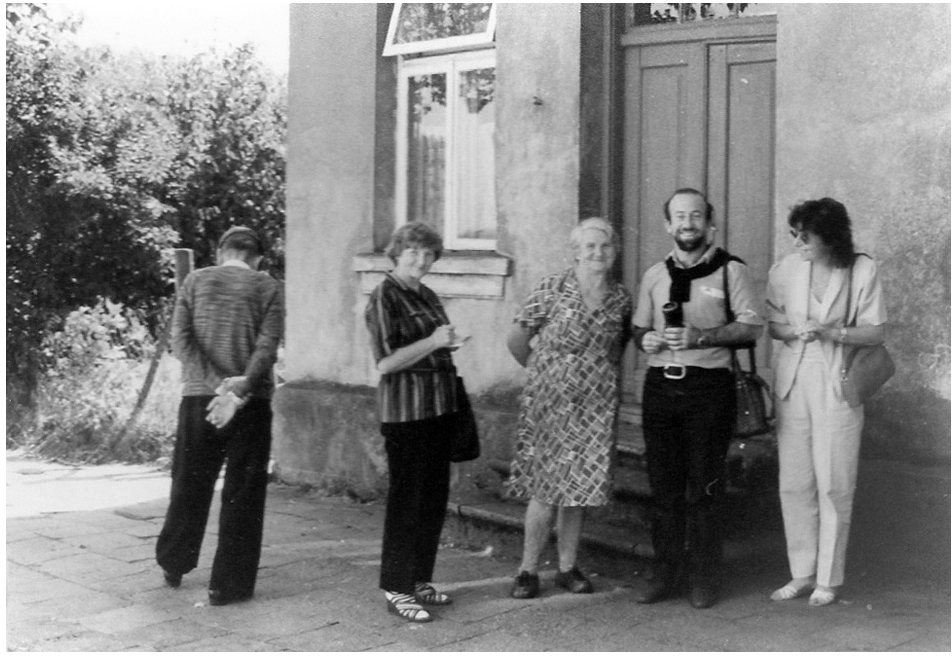

Silvio Gutkowski

With Mrs.Slazka, Mrs. Konopka and Cora Fueguel during my visit to Serock in 1983.

translation - in this case, myself - is being transformed by the very content of the work. And I concluded that if I did not do it by myself, nobody would do it, and if so, many significant events of our personal and family histories were to be lost and forgotten.

I will try to explain it better: Yiddish is not a language I usually speak or read, I just listened to it during my childhood in Villa Crespo, in the house of my parents; my father who came from Serock, arrived at the Port of Buenos Aires in March 1930 in the ship Darro and read with more interest the Idische Zeitung (the Yiddish newspaper), every morning at our house, then the newspaper La Prensa* (*one of the leading newspapers in Argentina)

-13-

With the passage of time, Yiddish was losing speakers and readers, however, Yiddish stayed with me as an anchor in the story not told by my father. When he spoke Yiddish his attitude changed, he freed (released) himself, because it was certainly his language. Or when driving the car and humming, it was always a song in Yiddish. Moreover, when a cast of Yiddish theater came to Buenos Aires, which happened once or twice a year, he bought tickets for the whole family, we dressed elegantly, and we went together to see, in the Teatro Soleil or Mitre3 a comedy of Sholem Aleichem. In the frame of the show, my father usually met with his countrymen, and this day was a holiday.

The Book of Serock was thought and written in the language of my father and I translated it literally, always thinking of the author of each of the testimonies, as well as the imaginary reader, the Spanish speaker. I tried to stay true to both.

My father had left behind his parents and siblings. He left Serock with the last image of his weeping mother and his stricken father. In 1936 he married in Buenos Aires with my mother, Sarita Cordon, a native of Argentina, creolized as her family, who arrived in the country in the early XX century. Also in Argentina we were born, their four children. But while my father was saved, he could not help but feeling the pain of the great loss and the guilt for being unable to help his European family while he was still alive.

This book was translated in 2009 and,

during that time, Gutkowski's clan members from Argentina, Israel and Central

America were partners that sent to me 3 Both the Mitre as Soleil

were true theatrical Jewish temples.

---------------

-14-

their comments and reactions to the text flowing from one language to another. Together with them I realized that through the testimonies that make up the original book, we recover the history of our ancestors in Serock, a fact that strengthens our individual, family and social identity. We recover also a history and a culture, no less! - tending to be forgotten- thanks to this project is again recovered.

The original book was written by srotskers, Serock residents who survived the war and emigrated to Israel, the U.S. and Argentina. Each describes events that occurred before, during the war and after the war, in the vicissitudes of the liberation.

Texts in different and complementary perspectives coexist, allowing to reach a greater understanding of this hard period of European Jewish history and grant privileged access to culture that the Jews were able to develop in their small communities, when there was no television no computers, but there were books, writers, playwrights, theater and a rich political and community activity.

Following the suggestion of the original author of the book's introduction, Baruch Katzenelbogen, I suggest reading each chapter slowly. In this way, remember and honor the three thousand inhabitants of Serock, victims and martyrs of the Nazi regime, of which we are their heirs in culture.

At the end, I included a glossary to facilitate the reading. The translation of this book, the distribution, the transmitting are the legacy of the few who survived the darkest years of the history of mankind; they have taken the task to tell and write their

-15-

experiences for future generations. They are stories that make a narrative of horror and of human value and are a powerful call to life.

Silvio Gutkowski

-16-

Copyright©Howard Orenstein, 2021.