SEROCK: FRAGMENTS OF A FAMILY HISTORY

Lic. Hélène Goldsztajn de Gutkowski42

Buenos Aires

Translated by Edgar Gil-Haro

I

Serock, a name I must have heard thousands of times during my childhood. A name that at times evoked bucolic images of Jewish youth who coveted modern life and culture, and at other times: poverty, lack of opportunities, discrimination, the horror of persecutions.

Your name, Serock, is associated with the romantic dreams of my parents' generation, as well as with the injustice and the devastation. What has never before been seen or imagined, the unspeakable, are also linked to your name, Serock.

My tie to this Polish shtetele, in the good

and in the bitter, was born with me in another place, in Belleville: an old

working class neighborhood whose paved streets would rise to the height of one of

the hills of Paris. Many Polish Jews had settled there beginning in the 1930s,

my parents among others, and there we returned after the war, the same as many

other gueratevete*. I spent the second part of my childhood43and adolescence in

Belleville. You began to be a part of me there, Serock!

_________________________________

42 Grandmother to six descendants from a long line of srotskers, Hélène

Gutkowski is a graduate in sociology and board member of Generations of the Shoah

(Generaciones de la Shoá) in Argentina.

* gueratevete: In Yiddish, one who has been saved, or has escaped: A survivor.

43 The first part of my childhood, I

lived three years with a Catholic family in a town on the outskirts of Paris,

while my parents and my brother attempted to survive in the Free Zone.

-279-

The backroom of my parents' business was at once a kitchen, dining room, and a place to read the Jewish daily. It was also home for the few relatives and countrymen who arrived in France after having survived hell. I remember them with their backs sunken under the weight of what they had suffered; people with frayed and dark clothing. After having found themselves free, many went back home in search of their loved ones, and with the unbearable pain of not finding a living soul, they now returned to the France of Liberty . . . not so free, not so open, and not so hospitable, in those grey years after the war.

In the backroom, the heat

from the coal stove in the kitchen was comforting on cold days, but became

unbearable during the summer. The skylight was never very bright. My mother

couldn't stand it, and as soon as she opened the door, she'd turn the light on,

even during the day, and murmured: "Es zol zein lichtik in unser schtuben!"44, with

these words expressing Jewish eagerness, par excellence. Two sideboards that framed a solid

table completed what was all the backroom's furniture The few relatives and

countrymen, who had returned, sat around that table. They remembered, they cried.

Mourned were the siblings from whom they would no longer receive news, mourned

were the parents who would no longer write to their papirene kinder45. Mourned

was the calvary, unbearable to imagine, of so many children. Pain was shouted in

my parents' backroom, G-d was reprimanded, and afterwards . . . an

__________________________________

44 Let there be light in our homes! "Light", as an allegory of clarity,

harmony and happiness; and "homes" as a symbol of our family's and friends' homes, of life. In other

words: "Let us have a luminous life, without storm clouds."

45 Paper children. An expression that alludes to children who have emigrated; and paper, letters, as the only means of keeping in contact with them.

-280-

intimate prayer for the miracle of being reunited with a lost loved one, for a better tomorrow for the children.

The backroom of my parents' business, my mother's bitter tears, your name, Serock, once and once again repeated, and the nostalgia expressed in the lidelechs that my father sang, molded, I suppose, my personality, my empathy for those who suffer, and my fears, as well as that diffuse desire, banished for many years, to recover our family history. As a grownup, I've frequently asked myself the reasons for that type of sadness I always carry inside of me. I now know that I was immersed in the repeated cries of my mother, in the self-reproach of not having brought her loved ones back to France in time, in the feeling of guilt shared by so many of the gueratevetw for having survived, when many had not. . .

The walls of that backroom heard so many fervent pleas! And blessings and curses. Those deaf walls have heard thousands of questions, and not one response, to G-d who "had hidden from the face of the Earth during those five hallucinatory years." They were also witness to a few, very few, miracles of being reunited with lost loved ones after years of uncertainty.

My parents used to say, and I've heard it from their fellow-countrymen, here, in Israel, and in the U.S., that you were a beautiful town, Serock, of smooth hills and prairies with fruit-bearing trees. They recalled how the green waters of the Bug and the Narew made your shtetele different from the rest, with boats to ride in the summer and, in the winter, a good layer of ice for those who loved skating. Perhaps only those images would have remained in my memory, had it not been for a becherle, a ritual cup, images of

-281-

life silencing grief. And perhaps it never would have occurred to me to visit my parents' hometown . . .

had it not been for a becherle !

In 1983, I don't remember why, my husband and I decided to invite all of the Gutkowskis to a family reunion. One cousin brought with him a letter that, by strange coincidence, Silvio had mailed from Israel a few days before. In that letter, which was read aloud, Silvio narrated his visit to . . . Serock! He was the first person in our family to have stepped on Polish soil, something his parents would have never accepted, nor mine, or my husband's, or any other Polish Jew of that generation.

So intense for me was the impact of the narration of what transpired for Silvio during the visit to his paternal grandparents' house when, while speaking with the people who lived there, the woman suddenly turned her back to him, went inside the house, and returned with something in her hand. Giving it to him, she told him: "this cup -- this becherle -- belonged to your family; it will be better in your hands than in ours."

For some of us, the letter from Silvio marked a before and after in our connection with Serock. His time and my time, in a certain way, coincided. I'm referring to the "time" one must allow to pass in order to face, without excessive harm, a traumatic history. His example was the impulse I needed. To travel to Poland, to visit the town of our ancestors, took on, for me, from the reading of his letter, the force of a mandate. I should know the place where my parents had lived, where my brother had been born, I felt the need to search for family documents, papers, proofs, facts that would make me feel that we had real roots. I needed to place myself mentally

-282-

in that space and inscribe myself in a continuity that for too long had remained truncated.

II

Finally, in May of 2000, my husband, my sister in law Raquel, and I traveled to Poland in search of our own becherle . . .

The Serock of my imagination would finally situate itself in the actual Serock. With a map in hand, accompanied by a youngster (masc.) who translated for us, and with information we had received from my last two living cousins (fem.), one in Israel and the other one in France, we started our tour through the shtetl where several generations of Gutkowskis, Leibgots, Goldsztajns and Boguslawskys had lived. But . . . where to go first?

The choice fell upon Napoleonisher Berg, the Mount, or Hill, of Napoleon. That hill, mentioned and missed by all of the Serock survivors, must have been a magical place for the youngsters who would spend Shabbat there. Stolen kisses and declarations of love found a setting so idyllic there, just as the illusions they were weaving.

Later, we went in search of the Szdroi, the stream near the home where Iosef and Liba, my parents, lived after having married. The Szdroi flowed in the same way, without a doubt, as it had seventy years before, but no one could tell us which had been the dwelling I was searching for.

-283-

Hélène Gutkowski

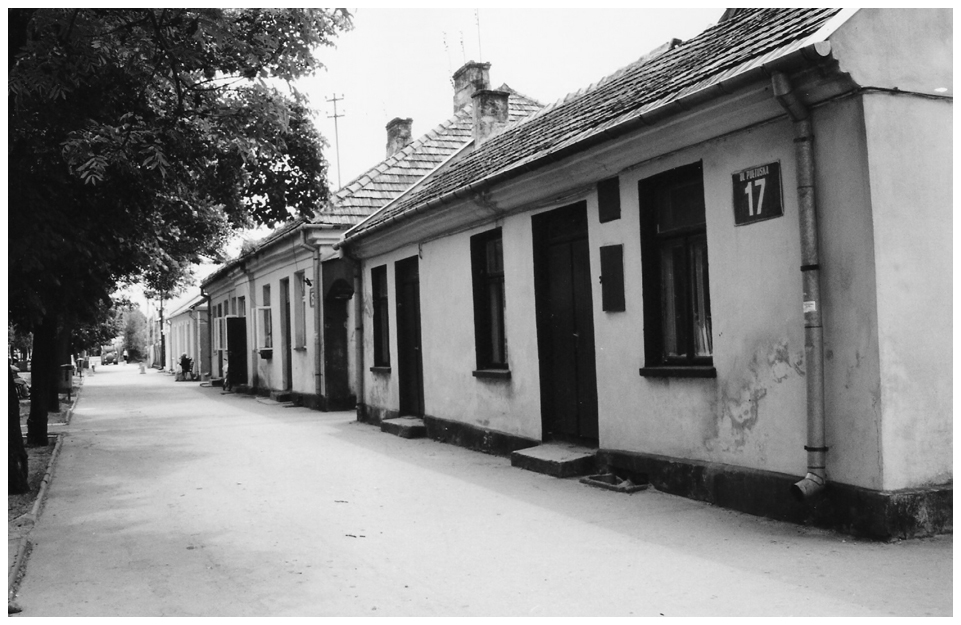

Third of May Avenue is part of the Pultusk Route.

On Third of May Avenue, on the other hand, it was not difficult for us to find the Berl Itzkowicz46 house, and later, at the town entrance, the flour mill that made this family one of Serock's most well off. The mill is no longer a mill, and no longer belongs to Jews; it was transformed into a metals factory and now belongs to the Polish state.The Market Plaza, the Rynek, had

been recently renovated, and the town hall completely reconstructed. Modern

benches and flowerpots gave it color without making the place, nonetheless,

________________________________________

46 Berl, husband of Bayla, my father's sister. Berl and Bayla's eldest daughter, Rachl, made aliyah before the war. Their youngest son, Haïm, emigrated to the U.S. at a very young age. Guitele and Surele managed to escape from the Varsovia Ghetto thanks to Polish friends and lived as Poles (fem.) until the end of the war. They arrived in Paris in 1951. Guitele's twin, Meir, ran a different luck . . . In charge of a team that left every day to work outside of the ghetto, he was horrifyingly attacked by a group of trained dogs, the day that one of "his" workers failed to respond to a control call as they were returning. Meir found his death when he jumped from the train that was transporting him to the extermination camp.

-284-

unrecognizable to me because that's exactly how the quadrangle was drawn in my memory through my parents' recollection. Closing my eyes, I could even see the vendors: men and women who came twice a week to buy and sell the little that Poland offered at the time: potatoes, onions and cabbages, beets, some chicken. Which of my two grandmothers was the courageous one who, in order to bear the five or ten degrees below zero (C) of winter, would place some type of brazier under the bench she sat on, in order to better endure the cold, until she finished selling her scarce merchandise?

On a slope below, we would go down toward the Narew River. When we were young, we gave little credit to the srotskers, when they spoke of how beautiful the river was. What did those men and women know of beautiful landscapes? But down below, the shocking mirror of water born of the union of the Narew with the Bug River, confirmed what our elders had expressed: it was beautiful! Natural beauty that doesn't always go hand-in-hand with the beauty of the human soul. . .

We returned toward the road when suddenly, a sign on No. 8 Kasciuska Street made me stagger. It read, "Bibliotek."

For an instant, the present and the past confused each other. Could that be the Jewish library my mother spoke of? No, it couldn't be "her" library, and strangely, at that moment, I knew we were very close to "her" house. At No. 10 of that same street, my cousin Marisha had told me, I would find the house of my maternal grandparents and their six children. A difficult sensation to transmit, to find myself in that place.

With an unrestrained heart, I asked two elderly women, sitting in an adjacent garden, if they had ever met the

-285-

Boguslawsky family, if they remembered my grandparents, if they knew of the fate of my aunts and uncles . . .. Surely they must at least remember my grandfather, Reb Hersch Froim Boguslawsky, the melamed, the master of religion.

One of the women, looking at us coldly, said she had never met anyone with that name and returned to her self-absorption. The other one, more predisposed, spoke after a few minutes: "Yes, I do recall something, but I was very young then. What I do remember very well is the bomb that fell on the 5th of September, just here,"she pointed at the street corner, "and smashed the Rosenberg house to smithereens, along with the seventy-two people who found shelter in its basement."

Seventy-two srotskers, the first among an infinite list of Jewish victims, perhaps some of my relatives, or my husband's, among them.

"I also remember," continued the woman, "that day in which the Nazis expelled the town's Jews. They made all of them come out of their homes. I can still see how they made all of them form a long line and ordered them to walk on Kasciuska Street, toward the Pultuske Shesai,47" showing us with her hand the direction in which the long human column moved, "toward the Nasielsk train station."

After returning to Paris, my cousin Surele

Itzkowicz, the only person of my parents' generation born in Serock and still

living, heard my story in silence and with a weakly voice remembered: "I was

there, in that line. I had returned from Varsovia, where I was living at the

time, a few days before, because the rumors that were circulating made me fear

the worst for my family. I was expelled along with all of them."

_____________________________________________________

47 The Pultusk route.

-286-

And she added: "Incredibly, despite the shoving, the blows, and the insults that accompanied our march, none of us imagined what was ahead. My mother, my aunts and I were all dressed in hats and gloves, as if we were going for a ride somewhere . . ."

A sad forefront fell upon the Serock community as the shtetl suffered, four short days after the beginning of the war, the impact of the first German bombs, the death of seventy-two of its members, being one of the first ones, also, from which all Jews were expelled.

III

Several years have passed. Serock is always in a little corner of my heart-memory. I now belong to Generations of the Shoah in Argentina, an institution that brings together hidden children, survivors, and children of survivors, and works in the diffusion and education of the Shoah.

There are still a lot of black holes in our family course and that which was experienced by my closest ones during the war. Not knowing carries a heavy weight, each time even more, and the desire to return to our shtetl to try to put together the fragments of my family history is stronger as time goes by. I am pressed to inscribe our saga in its space-time continuum and community frame, to recover the names of that great family that the war has stolen from me. To know how many there were, who they were, what their dreams were . . .

To be able to place the present and the future of my children and my grandchildren over a past with first names and last names. Could it not be, some day soon, a utopia?

-287-

Until recently, I felt alone in confronting this project. . . I couldn't hear enough echoes around me.

And here it is, more than a year later, Silvio announced that he was coming to Buenos Aires and told us of his wanting to be reunited with all of the Gutkowskis. For the second time, Silvio's motivations, at some point, were going to cross mine.

There was then a new reunion with the whole family, this time with Silvio, and with the third and fourth generations. The emotion was enormous, everyone felt summoned, the adults, as well as the children. Two projects were born of that reunion: the Gutkowski family tree, a magnificent undertaking by Pablo Gutkowski, representing the third generation, and Silvio's commitment to translate the Sefer Serock into Spanish.

The Sefer Serock, the Book of Serock, is a compendium of stories written by a group of survivors from our town, referring to life in the shtetl, before, during and after the war.

Many of us had received it from our parents as a legacy, but I don't believe anyone had read it yet, because of the difficulty it meant for the majority of us to read in Hebrew and in Yiddish, even though . . . perhaps it was because no one was prepared to come near, during all of those years, that painful past.

Silvio understood that the book amassed testimonies that were relevant, not only to the tragic years of the Shoah, but also to previous eras, histories that had to do with all of us and that we should have the possibility of reading it to consolidate, as he expresses it, our individual, family and social identities. In that way, once again, he was a pioneer . . .

-288-

For more than a year, members of the Gutkowski clan began receiving, via email, the Spanish version of The Book of Serock. Silvio's will to recover our roots was a lot like my longings, and the translation he undertook gave me the stimulus I lacked. Notwithstanding the obstacle of language, what I remembered of my parents' stories had been confirmed! Every delivery took me back to the backroom of the family business, there in Belleville.

In Iosl Grossbard's story, the same nostalgias resounded those heard from my parents, seventy years before; but what moved me the most from his article is that it is written in the same romantic style unfurled by my mother in her brief moments of tranquility, when she sat down to write poems. Could they have both belonged to the same group of young srotskers, poetry enthusiasts?

To read Haim Kapetsch was also like listening to my mother who, he has now proven it, did not fantasize when she spoke of the rich cultural life in Serock: of conferences, of the plays they presented, of the library.

Story after story, I recovered what I listened to as a child, putting two and two together, and enriching my knowledge of shtetl life, and also, in regards to the German invasion of Poland, and the persecutions. I began to notice, through this reading, that the war began by taking down Serock, in two of its cruelest dimensions, more than a year before the rest of the Jewish communities of Europe. The strategic war, on the one hand, was war for "vital space," and on the other, war against the Jews.

For the few srotskers who survived the horror, the war lasted six very long years. The stories of Feige Kanarek and Bracha Pszikarsky explain it: the war front could be found

-289-

only a few kilometers away from Serock, from there the Nazis needed to establish their base in town and install, from the very beginning of the war, a battery of heavy artillery. I now understand this to be the reason why our people were expelled so hurriedly, but if we do not also take into account the concept of "war against the Jews," we cannot comprehend the brutality, the viciousness, and the sadism with which this expulsion was carried out.

The accounts of Havvah Concal Kanarek, Jacob Mendzelewsky, Zvi Kleiman and Abraham Spilka corroborate the presumptions that are made of the preceding: our town had been a type of practice laboratory for the Nazis; in Serock, they experimented with methods that would later be applied to the rest of the Jewish communities: plundering, concentration in the synagogues, grotesque and humiliating mockery, indiscriminate punishment, torture, expulsion, trampling, beatings, executions by firing squads, deportation.

The order to exile on the 9th and 10th of September concerned only adult men, but that of the 5th of December no longer took anyone into consideration. All of Serock's Jews had to leave. Three-thousand Jews from whom everything was taken, three-thousand people uprooted from their homes, directed toward the Pultuske Shesai, with their elderly and their ill, with their babies. Pushed, squeezed together and beaten, humiliated . . . three-thousand people, eighty of whom were related to me. "I was among them," Stacha had told me. And the pain in my chest is no longer just for Surele48, it has multiplied by three-thousand!

Zvi Kleiman's article, where he describes the coming and going of

trains, in one banishment and another, demonstrates that,

_____________________________________

48 Surele: In Yiddish, a diminutive of Sarah, or Stacha.

-290-

in both expulsions, in September and December of 1939, the Nazis weren't yet clear what should be done with the Jews. The machinery of death, the final solution, would be sketched out in Wannsee, in January of 1942, which did not hinder them, a priori, from ferociously using brutal treatment, as recalled by Kleiman, as he describes the "unheard of sadism of the German perpetrators in the concentration of the 10th of September, 1939," when five hundred men were brutally exiled, and many of them, assassinated . . .

The 5th of December of 1939, the day in which all of the town's Jews are expelled, is a very cold day. In that harsh winter of '39, the majority of all the rivers have frozen. The uprooted arrive, some at Jablonna-Legionowo, where the Law of the Ghetto has been enforced with full vigor, others at Biala Podlaska, and the rest at Varsovia, where the ghetto would be created a year later, in October of '40, and would be sealed in November of '41.

As remembered by the majority of the authors, the srotskers were forced to abandon their homes under shouts, insults and all types of physical abuse. My mother's mother, three sisters and two brothers, along with their respective families ended up, I am not sure if by their own choice or not, in Jablonna, a small city situated fifteen kilometers south of Serock, also on the edge of the Narew river, but on the opposite bank.49

A few days after settling in Jablonna, who

knows where and how, my grandmother, in a crazy attempt to recover the small

savings she had left hidden in a wall of her house, decides to return to Serock.

She managed to slip away from Jablonna at nightfall, imagining that the darkness of the

______________________________________

49 One of my father's brothers, Shulem Goldsztajn, lived in Jablonna. He escaped to Uzbekistan where he found another brother, Leibele, and survived, not so his wife and daughter.

-291-

night would protect her and that the frozen river would be the ideal shortcut. She arrived in Serock and managed to obtain her meager treasure, but she never returned to Jablonna. The layer of ice over the Narew was not yet level and in the very middle of the riverbed, and of the night, the ice gave in under her feet.50 My guts twist just thinking of her desperation, poor grandmother of mine whom I never met, when she understood that she would remain there, swallowed up by the frozen waters of the beautiful Narew. Her name was Ruchcia Zylbersztajn.

A meager consolation to think that her frightful death was less horrifying than the nameless suffering of hunger and of the extermination camps . . .

Of my uncle Shaie, dear brother of my mother, I learned recently, also from my cousin Marisha, that he was taken down by Nazi bullets while trying to bring food into the Jablonna ghetto. His wife and three daughters, my cousins, were all deported. How painful it is to write these words when it deals with your own family!

Could Shaie have been able to escape his destiny? Why wouldn't he have stayed in Buenos Aires, where he arrived in the '30s with a group of youngsters from Serock? He had found work in Mendl Kuligowsi's carpentry shop, another fellow-countryman. Shaie could have forged a peaceful situation there for himself. But no, he missed the shtetl life and he had returned to Serock a few months before the war . . .

Until here, a

recovered history, thanks in great part to that "starting mechanism" that

signified Silvio's decision to translate the Sefer Serock into Spanish. There

are still a lot of missing pieces in that great puzzle of our family history, but

the first few steps have already been taken . . .

______________________________________

50 Source: My cousin Marisha, who received the information from a town survivor.

-292-

Copyright©Howard Orenstein, 2021