|

| Table of Contents | ||||||

|

|

Maps |

|

Bibliography | |||

|

|

Aerial Photographs |

|

Documents | |||

|

|

Pictures |

|

Individual Families & Names | |||

|

|

History |

|

Searchable Databases | |||

Some details:

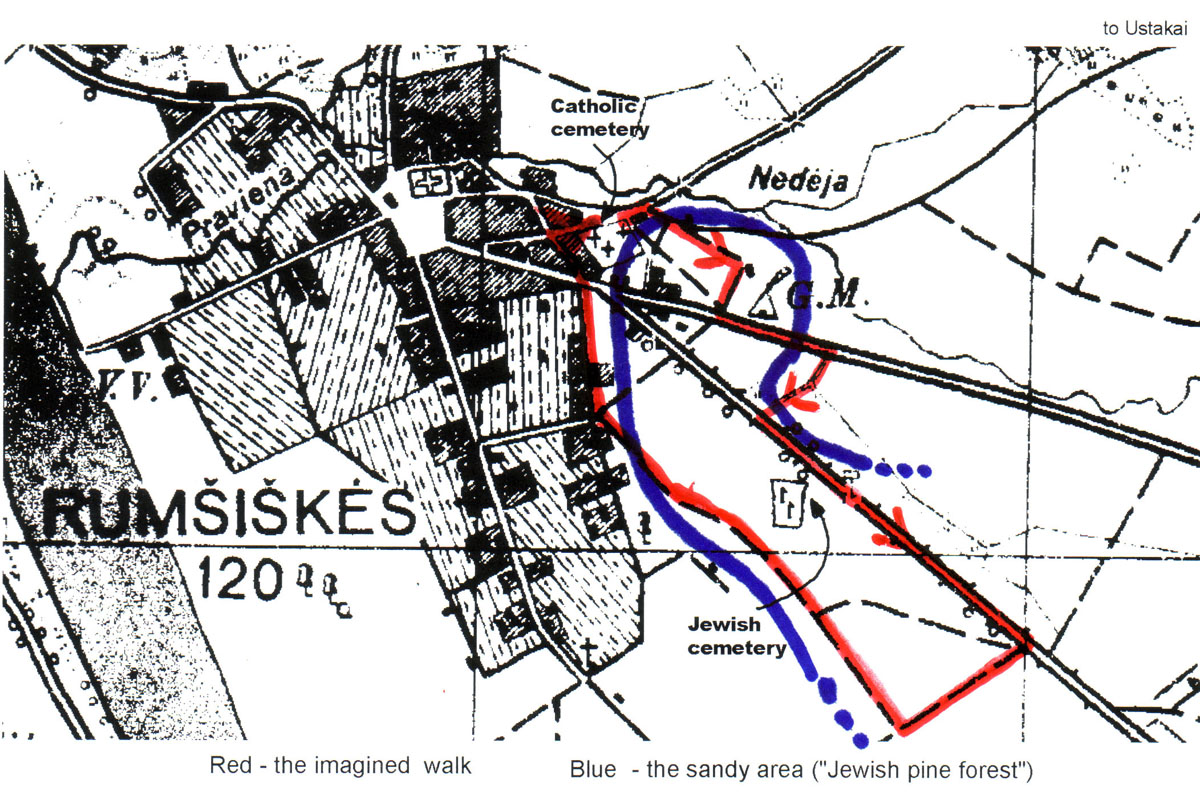

..1. The "Jewish pine forest" is a good-sized sandy area, so called because the Jewish cemetery actually was in a small pine forest in the middle of the area. The map below shows the "walk" as well as we can reconstruct it, and the approximate boundary of the sandy area.

..2. The title, "People Drowned You..." refers to the author's nostalgia for this sandy area, after the old town and its surroundings were flooded by the dam at Kaunas.

..3. Our gravestone photos from 1922 (see Pictures) show in the background just a picket fence, presumably surrounding the cemetery. The author remembers the cemetery as it was later. Presumably the stone fence he describes was constructed some time after 1922.

..4. The description of the structure at the entrance to the cemetery is a little ambiguous. It appears that the structure was small, but large enough to permit some ceremonial activities. It could be anything from a gatehouse to a small hall.

Although the presence and levels of Lithuanian anti-semitism in 1941 are not directly connected with this story, the question was raised when the story was first translated, so a few comments may be in order. Obviously, some Lithuanians were murderously anti-semitic, and made even more fanatical by the fact that the hated Russians appointed Jews to official positions, when they invaded in 1939. Equally obviously, some Lithuanians and Christians were personal friends of each other, and some Lithuanians actually risked their lives to save Jews. The question is, what did the in-between majority of the Christian community think?

Skietele's story would suggest that although the gap between the Jewish and the Christian community was wide, with mutual ignorance on both sides, there was little actual hostility. The Jewish sand-buyer in the story is portrayed as performing a minor act of kindness for the child Skietele. The memories of the translator (Ms. Zukaite) give the same impression; she remembers conversations with her grandparents, where they said that most people had little or no hostility toward the Jews who shared their town (not Rumsiskes). It has been suggested, however, that these memories might have been a bit "sugar-coated". Regardless of what the true answer is, the story indicates that most Jews and most Christians had little or no social contact, that many or most Christians regarded the the Jews as a different and exotic group, and that old-wives' tales persisted (even when the children themselves found one to be untrue).

- V. M.

From P. M. Mikalauskas-Skietele, "Apie Rumsiskiu, senove, miskus, burtus ir velnius" ("Rumsiskes past - woods, magic, and devils")

One end of our garden bordered what we called Jewish Pine Forest. It was a 300-hectare piece of yellow quicksand. On that big piece of land hard, tree-high tufts of grass and two kinds of moss grew several feet apart from each other. Some of them were light in color, almost white, half a meter tall. They had conquered almost all the Pine Forest, and were not eaten even by goats. Others - green, of similar size, but a bit more gentle and softer. Small patches of that green moss shone here and there, and in between them grew those so-called turnips. The turnip heads were composed of lots of tiny leaves, completely without stems, as if they were glued to the sand. From above, the turnips looked like flattened heads of cabbage, only one hundred times smaller. [Christian] Women adorned graveyards with the turnips - they would make crosses, stars, it's just that it never seemed to me that they took root there.

On the edges of the Pine Forest, closer to the farmland, here and there one still could see patches of grass that we called catballs, and half-a-meter tall night flowers that would blossom yellow at night. And that's all. Even mint didn't grow in those sands. The whole piece of land was covered with hills and valleys. Only three buildings were standing on it: a sauna that burnt when I was small, a house of a Jew and a diesel mill that belonged to the same Jew. After the war Russians took with them that big diesel that turned the grindstones of the mill, and our people ripped apart and took the boards from the walls of the two-story mill. And that way the mill ended its life.

There was a Jewish cemetery - magylos1 - in that sand desert. Thick pine trees grew in the cemetery. Magylos was fenced in by a two-meter-high fence made of boards and stone; there was not a single crack left. In one corner, leaning against the fence, there was a small building. It didn't have any windows, just a meter-wide doorhole without a door. There was also a meter-wide hole in the fence. That hole was used to pull in a coffin of a dead Jewish man or woman brought there in a wagon. Here is how it used to be: the Jews that escorted the coffin would get in through that hole, perform some kind of rituals, and then they would carry the coffin to the gravesite. The gravesite was not deep, up until the armpits of an average Jew. Then they would take a dead person out of the coffin, half-seat him in the grave-hole covered with planks, put a piece of a broken plate on his face, cover the dead person who was wrapped in a cloth with boards, and then dig over those boards with a reversed spade. When the boards could not be seen through the sand, they would start digging in the usual way. There was not a single gate in the cemetery fence. We kids would squeeze in through that hole into the cemetery and look for money. Because we had heard that while carrying the coffin from that small building to the gravesite, other Jews would throw money on the ground for the carriers. It is probably not true, because we would never find a single cent. And there was only one coffin for the whole Jewish community...

In the Pine Forest the Jews pastured their cows. Every year they would hire an elderly man for that - a shepherd. At sunrise he would blow his long pipe so hard that the whole town could hear it. And so he would pasture, or to be more accurate, chase those Jewish cows in the Forest, because there was nothing edible there...

The Forest was dry. It could rain day in and day out, cats and dogs, but it stayed dry no matter what. The yellow sand in the Forest swallowed up all the water like a strainer. I remember, we would dig a hole with other kids, but we would never find water in it as we would never find money in Magylos. It probably just flowed into Nedeja that ran on one side of the Forest.

Let's go. I'll show you around the Forest. We'll start with the Catholic cemetery. We are walking along the metal fence to the north up to the road that leads to Uztakai. A little bit left of the Uztakai road we find the Nedejos, a little river that dries out in the summertime. On the other side of the little river there are the farmlands of Klimas, Ulozas, Sadauskas. Walking on the left bank of Nedeja against the stream, maybe half a kilometer down the road, we'll come to the so called "Slaughter Road". It's a narrow path that leads to Uztakai and reminds one of a lot of things from WWI. And when we need to part with the small river and turn south, then we will step onto the old Vilnius-Kaunas road. Let's go, my friend. We are now walking up a rather steep hill. Doctor Ulozas' piece of land is on the left hand side, and the Forest and the Jewish mill are on the right. Three to four hundred meters up the road, we start descending the hill onto the new Vilnius road. This road has carried on its stony back not only the farmers' wagons with pigs, geese, cheeses, butter and other treats to Kaunas, but also the Polish, Russian and German troops. Let's turn to the left. It's hot - would be nice to get something to drink. But remember, my friend, we are walking in the Forest, where there is not a single drop of water. Hang in there - keep on, we've made it almost a third of the way... On one side there is the land of the Ulozai family (belonging to Daktaras, Sikis, Gruzinas, Gorciukas [most likely nicknames of the Ulozai family members]), and the land of the other Ulozai family from Paniedejai [place name?]. On the right you can see the Jewish cemetery.

After having walked on the asphalt road we turn ninety degrees south, by the Dementaviciai farmstead (near Skatikeliai), and go further on until we reach the old Gardin road, which some people used to call Kruonkelis. The road continues along around 700 meters through the farmlands of Sadauskas (Azuolas) and Ignataviciene (Zaniene). From Kruonkelis we are headed in a northwest direction. Having left behind the land of the three brothers Asilaviciai and Zakarauskas (Vistinis), and the outskirts of the gardens and having also passed by the asphalt road and the old Vilnius road, we finally end up at the starting point of this tour - the [Catholic] cemetery fence.

As you see, we have walked along the whole edge of the Forest. If I asked you now, what had you seen beside moss and sand, you would say - nothing. It's because we were walking on a warm and sunny day without the sky promising any rain. But if we had walked just before it rained, we would have seen a plethora of toads. Not a dozen, not a hundred, but several thousand of those striking creatures. They make their way through the Forest in rows, but only before the rain. [...] But you wouldn't see them on a hot summer day. That's how the Forest would let us know whether it would rain tomorrow or whether it would be clear skies.

While looking for money in Magylos, we would sometimes get to see other inhabitants of the Forest - small lizards. They were gray, some six-seven centimeters long, had four legs and a long tail. They lived only in Magylos. I would be a liar if I didn't mention that there were also a lot of crow's nests in the pine trees of the cemetery. They would hatch there and put up such concerts that you could hear far away.

The Forest was useful to us in the wintertime. At school, when you finished an exercise book, you had to show it to your father, then you would get two cents for a new one. But sometimes you happened to stain an exercise book. The teacher wouldn't correct a stained one and would demand a new one instead. If you showed such an exercise book to your father, not only you wouldn't get two cents for a new one, but he would ground you. What could you do? The Forest gave us a way-out. Back from school you would throw your backpack on the bench, grab two bags, a spade and a sled and run to the Forest. The sand didn't freeze there even in the wintertime. You would dig the bags full and take them to the town. A Jew would come out and say:

- Hei, kiddo, do you sell those bags?

- Yes, I do.

- So, how much do you want, how much do you ask for them?

- 10 cents for one bag, 15 - for two.

- Oh, well, OK. Pull over, empty here.

- No, give me the money first.

- Oh, what are you so afraid of, have I ever swindled you, have I ever kept what belonged to you? Pull over and empty here!

What are you gonna do, you need that exercise book real bad, you just pull the sled over and empty the sand where the Jew wants. The Jew comes, gives you 15 cents and an exercise book into the bargain.

- Just take it, I know you need money for exercise books, take it.

I say thank you, but I don't kiss the Jew's hand, as my parents have always taught me. If it is still light, I bring another load - and then I am rich, have enough for exercise books. Most important, I don't need to ask my dad.

Now you are under water, my dear Forest. People drowned you. They gave you so much water that you wouldn't get during the heaviest spring rains. Your sand filters cannot strain out that much water. Moss, turnips and lizards - they all disappeared... And you probably don't resist the water at all if the same depth of water is holding onto your sandy back.

- Translated by Laura Ziukaite

1 - Translator's note: Magila is Russian for "a grave". Since the author uses rather colloquial language, and not exclusively standard Lithuanian, the text contains a few loan words and old expressions that at that time were simply an integral part of the language because of different cultural influences.

- V. M.

Rabbi Ben-Zion Saydman

Compiled by Vic Mayper and Benzi Saydman

Web site layout and banner by Jose Gutstein

Updated by VM: April 5, 2010

Updated by rLb: April 2020

Owner: Rabbi Ben-Zion Saydman

Copyright © April 2020

JewishGen Home Page | ShtetLinks Directory

This site is hosted at no cost by JewishGen, Inc., the Home of Jewish Genealogy.

If you have been aided in your research by this site and wish to

further our mission

of preserving our history for future generations,

your JewishGen-erosity

is

greatly appreciated.