|

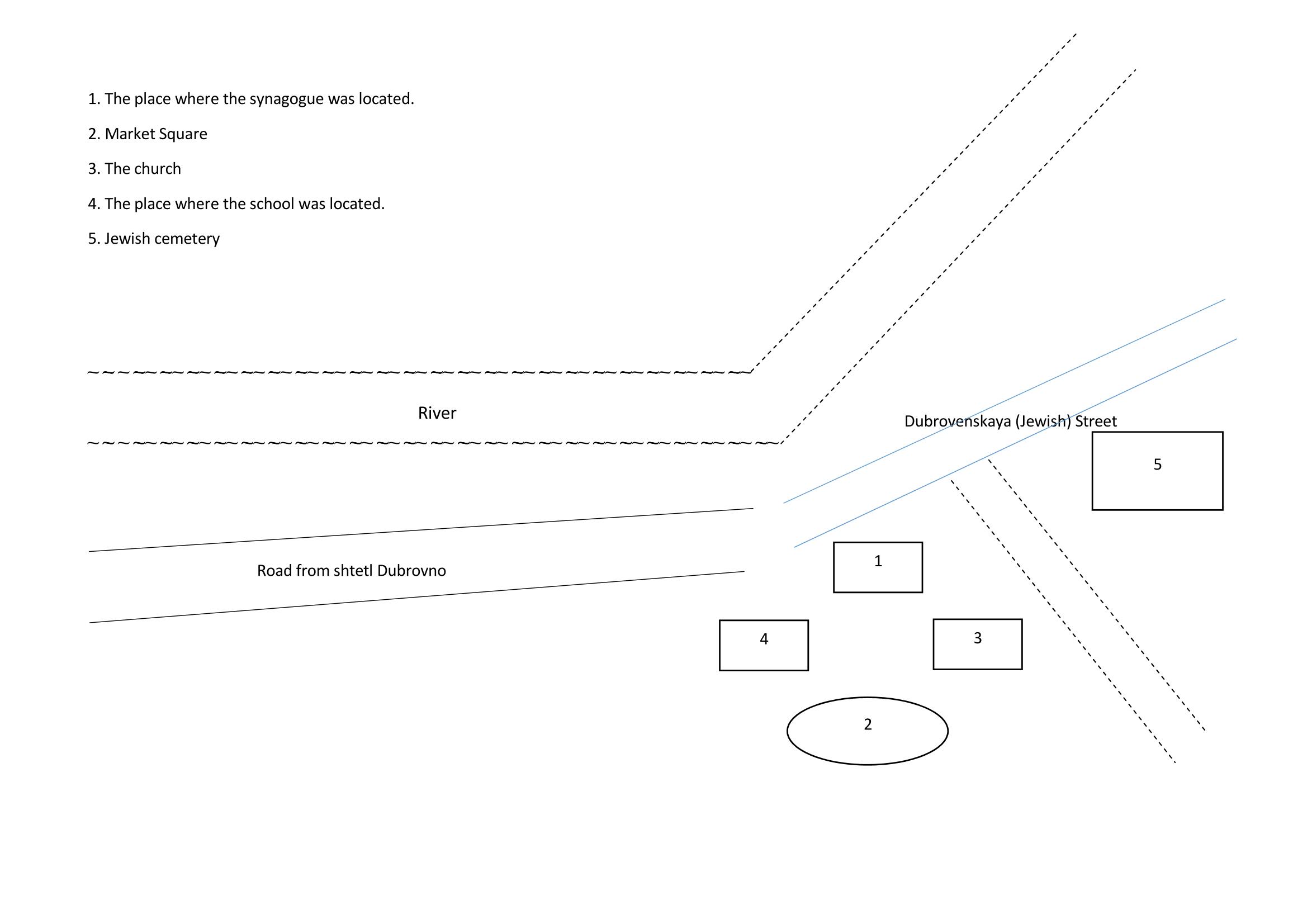

My family lived on Dubrovinskaya Street. It was named such as it was the street leading out of town to the nearby shtetl of Dubrowna. It was nicknamed “the Jewish street” as only Jews lived there. During WW II, the majority of the houses were destroyed, though a few pre-war houses remain. The street has mostly been rebuilt, and the name changed to Dneprovskaya Street. During my research, local residents that were interviewed remembered the USVYATSKY family, but their exact residence could not be identified. The street is about a two minute walk from the location of the old synagogue, and about a five minute walk to the cemetery. Between the cemetery and the synagogue is also about a five-minute walk.

(click to enlarge) |

||

(click to enlarge) |

(click to enlarge) |

(click to enlarge) |

The other street that was primarily occupied by Jews was Orshanskaya Street.

My family owned a korchma, which is sort of a combination inn and tavern. Probably most of the clients were non-Jewish peasants. Tavern-keeping was a very common occupation for Jews dating from the Middle Ages, offering one of the few means of livelihood, as Jews could not own land, and were often expelled from major cities. For example, in 1875, in the Goretzky District, there was an auction for people who wanted to obtain a license to sell vodka. All four of the individuals who received licenses were Jews. In addition, my family received permission to have a post office in the korchma, the services of which were paid by the State. People could bring their letters to the korchma for mailing, and receive their mail there as well. The mailman could stay overnight in the korchma while on his route, and stable his horse there.

The synagogue was near the town center where the

majority of the Jewish population used to live.

It was located between the old church and the market. Males who belonged to the

synagogue were eligible for voting privileges if they owned property or made a

donation to the synagogue. Before the war the

synagogue and Russian Orthodox Church were closed by the communists. The synagogue, a two story wooden building, was

demolished in the 1930s. The church was

converted into a granary. Locals said that during WW II more than half of all

the houses in the town were burned; that's why, in the pictures, houses look like they

are far from the center of town. The

church and the market burned down during the war and were never rebuilt. The church wasn't rebuilt because at the time

religion was forbidden. According to

locals, 20 years ago people could still see the foundation of the synagogue.

Now all you can see is a field.

(click to enlarge) |

(click to enlarge) |

According to residents interviewed by my researcher, in the 1920s and 30s, many people were poor. Adults, both Jews and Christians, worked at the local collective farm. This was a very difficult job. They were not paid, but rather worked in exchange for food (milk, eggs, grain, flour). Collective farm workers had no passports: this was done to prevent them from leaving for larger villages. Some people in the village were skilled artisans—the father of one woman interviewed was a cooper, and the barrels he made were highly prized, not only in Rossasna but also in the surrounding area. Children’s life expectancy was low—for one family interviewed, only 4 of 9 children lived to the age of 18.

Jews and Christians interacted frequently. Their children went to school together and formed friendships. Many of the teachers were Jewish. Before the war, many Jews held executive positions, worked in local shops, were school teachers. There were several “mixed” families. People interviewed felt that Jews and Christians got along well. One woman related the story of a local Jew named Efim who was walking through the forest and saw a boy drowning in the river. He saved the boy, who turned out to be her cousin.

At age 16, all

young men had to register for the draft.

At the age of 20 they had to appear before a medical committee. If there were health issues, or if the person

had been hospitalized during this time, that person was discharged and did not

have to do military service.

Additionally, according to an 1874 law instituted by the Czar, if a

person was married with at least one child, they would also be discharged from

military service. Military service could

be postponed if a person was in school (for instance a vocational school). Otherwise, military service started at age

21.

In Rossasna, there is a monument to the soldiers of the Red

Army who liberated the town and the surrounding areas from the German

Army. Locals say a lot of soldiers were

killed in this area; their bodies were collected and buried in a common grave.

Today, the current population of Rossasna

is only 329 residents. Most of them work for the collective

farm. The day care has 26 children. There is one school for 44 students, but it is

scheduled to be closed in 2018. Students will then attend the school in Dubrowna. There is

one daily bus from Rossasna to Dubrowna. There are two grocery stores and one clothing store. Many of the little towns and villages in the

Vitebsk region have been shrinking, as people leave them for larger towns.

Created by JP February 2016

Last updated by JP January 2018

copyright © February 2016 Judy Petersen

Email: Judy Petersen

| Belarus SIG

Home Page |

JewishGen

Belarus Database |

KehilaLinks

Home Page |

||||

Jewish Gen Home Page | ShtetLinks Directory

This site is hosted at no cost by JewishGen,

Inc., the Home of Jewish Genealogy.

If you have been aided in your

research by this site and wish to further our

mission of preserving our

history for future generations, your

JewishGen-erosity

is greatly appreciated.