Plunge, Lithuania

Leibas Bunka, A Double Volunteer

by Danelius Merkelis

Our thanks to Abel Levitt & Eugenijus Bunka for making us aware of this article

Leibas Bunka in Plungė, circa 1921

Born in Šilalė in 1895, into the family of cantor Jakovas Bunka, Leibas Bunka and his younger brother, Dovydas, were orphaned early. Nobody knows what really happened, but the spoken history of the family has it that the brothers found shelter in the home of their relatives Izraelis and Gita Efros.

Izraelis had graduated from the University of Berlin, where he studied chemistry, Gita – a dental practitioner. For a while, they lived in Plungė. Here, on November 1, 1914, they had their son Boris, who later became a celebrated Lithuanian doctor, an honorary member of the Vilnius Surgeons Association and Lithuanian Cardio-Thoracic Surgeons Association, Doctor of Medicine, who was the first to perform an elective heart surgery in Lithuania. It happened in 1958.

From Plungė, the Efros family moved to Šilalė along with the two orphans, Leibas and Dovydas. In 1920, they moved to Kaunas. Dovydas, who later became a teacher and journalist, moved to Kaunas with them.

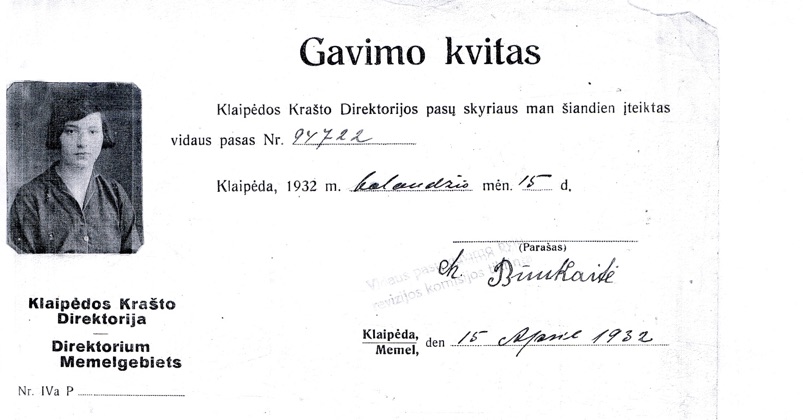

It seems that there was a sister born in 1907 – Chaja-Chasė Bunkaitė. Apparently, she was orphaned very early in life and raised by some relatives or childless Jews. However, there is no information on whether the brothers and their sister ever crossed paths. Almost a hundred years later, it was discovered in the archives that on April 15, 1932, she received Passport No. 97422 from the Directorate of the Klaipėda Region.

We can only guess if Chaja-Chase was the younger sister of Leibas Bunka, but her father’s name and the place and time of her birth allow us to think so.

When Leibas was twenty-two, big changes began in Lithuania, after which the country regained its independence. But it still had to be defended. Leibas was one of the first men who signed up as volunteers in the Lithuanian army and took part in battles for the state’s survival.

He later joked that in the army he was given a Russian greatcoat, a pair of German shoes, and fought against both the Russians and the Germans.

Again, there is no information as to where and in what battles the young man participated, but, apparently, he was a good soldier, because, at the end of the war, he did not come back to Šilalė, but was sent to Plungė to start a gendarmerie there.

In times of turmoil, there were robbers, thieves, smugglers on every corner, so there was enough work for the gendarmes. People say that after the declaration of independence Plungė even had something like a mafia. Both lowlanders and the Jews had their own competing gangs. Since the gendarmes were after them, the gangs united, but soon they dispersed.

Meanwhile Leibas met Taube and married her on December 28, 1920.

Taube-Eide Rilaitė came from a family whose ancestors had moved to Plungė about three hundred years earlier when Plungė took the title of the district center from Gondinga.

The house built by Taubė’s parents in the then poor city area on Rietavo Street still stands today. During the interwar period, the number was 25 now the number of the building is 21. The house was tiny, but it accommodated the newlyweds, the bride’s parents, an old relative, and even a huge wood-fired oven where Taubė’s parents baked bagels which they later sold thus earning their bread.

Taubė’s father Mendelis was known in Plungė and the surrounding area as a healer. His grandson Jakovas, the son of Taubė and Leiba has said how, through a crack in the door, he would watch his grandfather run his finger around a bottle of water and whisper something. Then the grandfather would give that bottle to a patient or his companions and tell them what to do with the water in the bottle. He accepted no remuneration, saying that it would destroy his power to charm.

But he would accept gifts brought by the grateful patients once they had been cured. Therefore sometimes there would be such treats as eggs, chickens, butter, sour cream – things they would normally only get during the holidays.

Jakovas asked his grandfather to teach him how to treat people. His grandfather promised to teach him when he is very old. But grandpa never got to live to ripe old age: on one of the first days of the war, he was killed in Skaudvilė together with his wife and one of Leiba’s daughters. They had gone to Skaudvilė to visit their daughter who had moved to the town after marriage. Therefore, the grandfather took his secret to the grave.

But this happened later. Meanwhile, in the early 1930s Taube and Leiba were raising four daughters and two sons in a small house.

Leiba Bunka’s family in Plungė in 1924. From left to right: daughter Dina, Leibas, brother Dovydas, son Jakovas, wife Taubė

Brother Dovydas also moved to live in Plungė. Girls went crazy about the good looking young man, one of them even tried to kill herself because of unrequited love. Perhaps this was the reason why Dovydas left for the United States. There he married and had children. He died in New York in 1976.

Jakovas Bunka wrote in his book The Jewish Page of Plungian History: “People of Plungė liked to invite my father Leibas Bunka to their get-togethers, weddings and other celebrations to entertain guests. Impromptu, he could create a song or poem about a person, based on their appearance or character. He knew many Jewish folk songs and legends, was a good singer and storyteller. He was literate. He would help people write requests to the courts and other institutions. A qualified clerk would charge a lot of money, while he charged nothing.”

Leibas was a true Jew, able to find the right thing to do and say in difficult situations, to make fun of them.

His youngest daughter Hana remembers how, while fleeing from the upcoming German Army to the East, the refugees stopped in some town by a rich estate. Leibas went inside to look around, and when he returned, he told everyone to leave the place as soon as possible because he had found proof that there the Red Army had had its headquarters there, so he felt that the Germans would soon bomb the place.

The tired people unwillingly rose to their feet, but when, having barely walked half a kilometer from the place, they heard bombs falling behind them, they agreed that they had been saved by Leibas’ military experience.

The next time was more tragic. The Germans shelled the column of refugees. Hana and her older sister Genė hid under a dead horse. The father, who found them, would later tell with humor that an unfamiliar horse covered his daughters with his body.

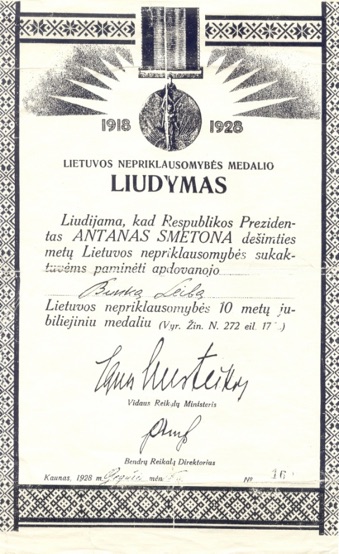

In 1928, the Lithuanian government awarded volunteers the Lithuanian Independence Medal, gave each of them a horse and building materials for a house. In the village of Babrungas, usually called Truikiai by the residents of Plungė, Leiba received almost eight hectares of land from the former Olgapolis manor. Now this is roughly the territory bordering with Laukų, Naujoji, Truikių and Linksmoji streets.

Certificate of Leibas Bunka’s Lithuanian Independence Medal Award

Leibas had no experience in agriculture whatsoever, so he did not dare to start the life of a settler. He leased those eight hectares, sold the horse and the building materials, found a job on the textile factory in Klaipėda, bought a house and moved there with his family. In the address book of the city of Klaipeda stored in the funds of the History Museum of Lithuania Minor there is a record that in 1935 worker Leibas Bunka was living in the house No. 1 on Aukštoji Str.

Only three years earlier, his sister Chaja-Chase had received the internal passport of Klaipėda Directorate, so it is likely that the brother and sister walked the same streets of the city, but never met. Chaja-Chasė’s fate is unknown.

The children went to school, Taube took care of them and newborn Hana, Leiba provided for the family. Life seemed OK, despite the occasionally hostile rhetoric of local German against the Jews and Lithuania. The children had German friends and spoke perfect German.

But Leibas actively participated in the activities of the Lithuanian Volunteers’ Union in Klaipėda, which got him in trouble with the local German organizations, his name even appeared in their blacklists.

One evening a German neighbor came by and told the family that she had heard that all members of the Lithuania Volunteers’ Union in Klaipėda were going to be arrested the next day. That same evening Leibas walked off to Kretinga and from there – to Plungė. Taubė’s uncle hired a carriage to transport the family to Plungė.

Leibas found work at the sawmill. He would leave the house for a week – in the forests of Stalgėnai he would receive felled trees, stack them in a sleigh or carriage and send to Plungė.

In the fall of 1939, interned troops from German-occupied Poland came to town. One of them was a Jewish officer who had escaped the Katyn massacre. Leibas and Taubė’s eldest daughter met him and soon married.

For their son Jakovas the parents predicted career of a rabbi, but upon their return to Plungė, he began to learn carpentry at the workshop of Šoblinskas, near the place where now there is “Plungės Jonis”.

When the Soviets came, Leibas continued to work at the sawmill.

Workers of the nationalized Plungė sawmill in 1940. Leibas Bunka sits second from the right.

On the Sunday in June when the Germans invaded the Soviet Union, the family meeting was very short. Dina’s husband, Leibas and Taubė put together their memories of how the Germans had treated Jews in Poland and Klaipėda, Leibas had also heard Hitler’s speech in Klaipėda, so all agreed to try to escape from the marching Third Reich. Taubė’s parents had gone to visit their daughter in Skaudvilė, so all that was left to do was pray for their survival.

But the worst predictions came true with a vengeance.

On that Sunday, the first day of the war in Plungė, childless Šoblinskas tearfully said goodbye to Leibas’ son Jakovas, several other escaping families were blessing those who stayed, sensing that they would never see each other again.

They walked more than three hundred kilometers to Daugavpils, under the rain of bullets and bombs from German planes, leaving the dead behind, losing each other and finding each other again.

After one of the bombings, Dina and her husband were unable to find their loved ones, so they decided to travel south. They ended up in Samarkand, where Dina’s husband subsequently died of starvation.

Only one and a half years later Leibas received her letter and learned that his daughter was still alive.

“My dear dear daughter Dininka, may you live a long life... Today is a big day for me because I have received your letter. I have got a letter that you wrote with your hand. I have cried out of happiness because you have been found. These past eighteen months I have hated my life, thinking where you were, but thank God, we can talk to each other again. I think we will still see each other, but God knows...” – he wrote to his daughter in January of 1943.

This was later, meanwhile, in Daugavpils, Leibas, Taubė and the children found a place on a train going east. In the stations, they would exchange their things for food. The train took them four thousand kilometers from Plungė, to the village of Voroshilovka, in Bolotny district of the Novosibirsk area. They were picked up from the railway station by a “merchant” – the head of the collective farm near the center of the district.

A Ukrainian refugee took in the family – allowing them to live in the bathhouse.

Only after the war it became clear that because Leibas was a Lithuanian volunteer, his name appeared not only on German lists, but also on those of people to be sent to Siberia by the Soviets.

However, the family had come to Siberia by itself.

Jakovas turned eighteen in mid-July, so he was supposed to be conscripted for the army. To prevent this, since he had no documents, his parents changed the date of his birth from July 13 to December 16. Although Leibas thought that the war was going to be long and brutal, he still hoped that a delayed birthday could save his son from the war.

Ironically, Leibas, however, became a peasant in the end: in the collective farm, he took care of the horses. Jakovas would help him. Destiny played a joke on him too: at the end of the war, he was serving as a scout at the Don Cossack Cavalry Corps.

Because war continued even after his delayed birthday, Jakovas was conscripted to the army in 1942.

The 16th Lithuanian Division was formed and whoever had any relations to Lithuania, even deportees, were made to serve there.

Leibas was almost fifty, so he was not eligible for the army. But suddenly he told his family that he would not let Jakovas go to war alone, because he would perish without the care of his father – an old experienced soldier. It was impossible to talk him out of it. Leibas went to the military commissariat and asked to join the division as a volunteer.

His prediction almost came true.

In mid-February 1943, the division commanders reported that the division was prepared for fighting, although the transport carrying arms and ammunition was still on the way to the front line, and it was impossible to dig trenches in the frozen ground. Small heaps of snow was the only protection against bullets.

In the fields by the village of Alekseyevka, in the Oriol region, the division received its baptism by fire between February 20 and March 20, 1943. It was also a place of the mass massacre of its troops. According to historians, out of a little more than 9900 soldiers of the division 5218 were killed, of which 4064 had come from Lithuania, 3215 were wounded, 159 went missing.

After an unsuccessful attack, Jakovas was injured and left lying in the snow. His father, who searched high and low for his son after the battle, found him and carried him to the field hospital on his shoulders.

“You know, my dear wife, I am unable to describe what is going on. Better, think that you will never be able to imagine this. My dear, I will suffer for you all. I am forty-eight years old, but I have to march on, even though I’m sick." – Leibas wrote to Taubė.

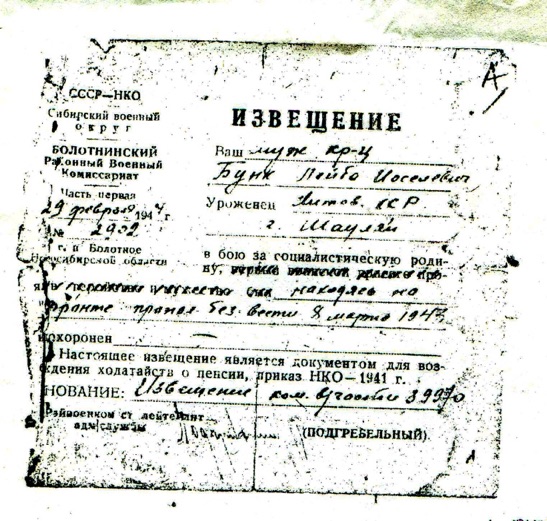

Jakovas ended up in the hospital of Zlatoust, but on March 8 Leibas was killed in battle. The family received a notice that he had gone missing, but, when Jakovas returned from the hospital to the front, he learned that a random mortar shell had exploded directly under his father’s feet. There was nothing to bury, therefore they said that he had gone “missing”.

Notification of the fact that on March 8, 1948 Leibas Bunka went missing in the battles at Alekseyevka tragic to the 16th Lithuanian division. The scribe made an error that he had been born in Šiauliai.

Almost simultaneously with the notification of the loss, the family received the letter, which Leiba had written a few days prior to his death. In the letter, he made no mention of Jakovas’ injuries. He knew that Jakovas would write from the hospital himself, so he saved the family in Siberia from the heartache over his condition.

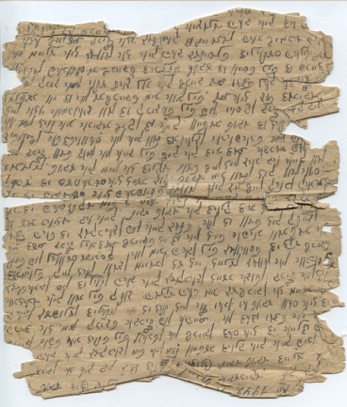

“My dear Taubele, Taubele, it would be so wonderful for all of us to be together again, but you have to believe, maybe God will let us see each other again. Do not cry, it will be all right, please write to me...” – these calming words came from a dearly loved person who was already dead.

Leibas Bunka’s letter from the front

Leibas’ younger son Abraomas, who joined the army later than Jakovas, had the same fate. At the end of the war, he wrote from Konigsberg, that he was beating the Germans and believed he was to come home soon, but instead came the news of his death.

After the war, the women survivors of Leibas’ family – wife Taube, daughters Dina, Gene and Hana – returned to Plungė. Jakovas, who had been left to serve in Germany, returned only two years later.

“If not for the war, my husband would have lived a hundred years,” – Taubė used to say.

She knew what she was talking about because Jakovas who was the spitting image of his father almost fulfilled her prophecy: he lived to be ninety-one.