Pinsk uyezd, Minsk gubernia

Pinsk-Karlin, Russian; pensk

1989 population: 118,636 1995 population: 130,000

Early Jewish Settlers.

Russian city in the government of Minsk, Russia. There were Jews in

Pinsk prior to the sixteenth century, and there may have been an

organized community there at the time of the expulsion of the Jews

from Lithuania in 1495; but the first mention of the Jewish community

there in Russian-Lithuanian documents dates back to 1506. On Aug. 9 of

that year the owner of Pinsk, Prince Feodor Ivanovich Yaroslavich, in

his own name and in that of his wife, Princess Yelena, granted to the

Jewish community of Pinsk, at the request of Yesko Meycrovich, Pesakh

Yesofovich, and Abram Ryzhkevich, and of other Jews of Pinsk, two

parcels of land for a house of prayer and a cemetery, and confirmed

all the rights and privileges given to the Jews of Lithuania by King

Alexander Jagellon. This grant to the Jews of Pinsk was confirmed by

Queen Bona on Aug. 18, 1533. From 1506 until the end of the sixteenth

century the Jews are frequently mentioned in various documents. In

1514 they were included in the confirmation of privileges granted to

the Jews of Lithuania by King Sigismund, whereby they were freed from

special military duties and taxes and placed on an equality, in these

respects, with the other inhabitants of the land, while they were also

exempted from direct military service. They were included among the

Jewish communities of Lithuania upon which a tax of 1,000 kop groschen

was imposed by the king in 1529, the entire sum to be subject to a pro

rata contribution determined upon by the communities. From other

documents it is evident that members of the local Jewish community

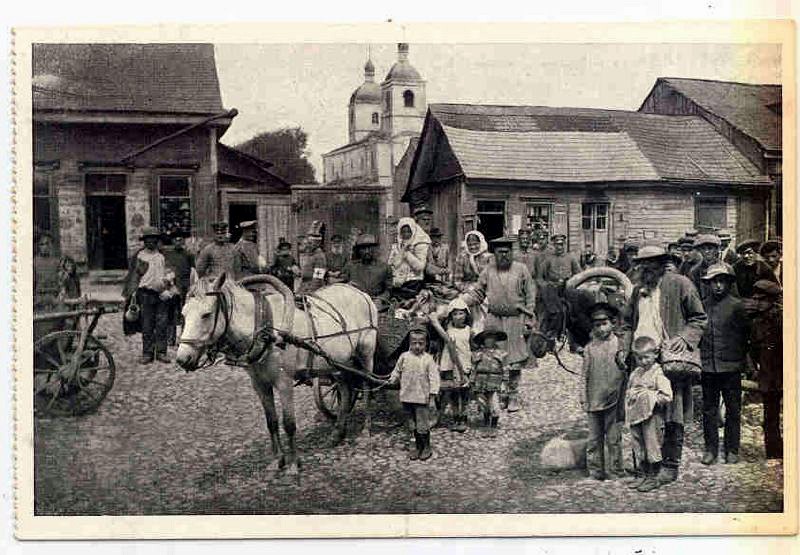

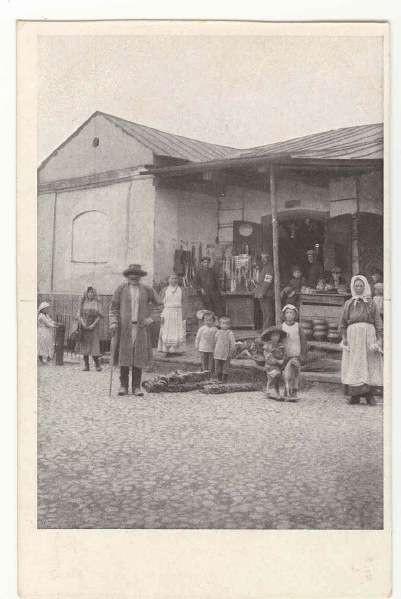

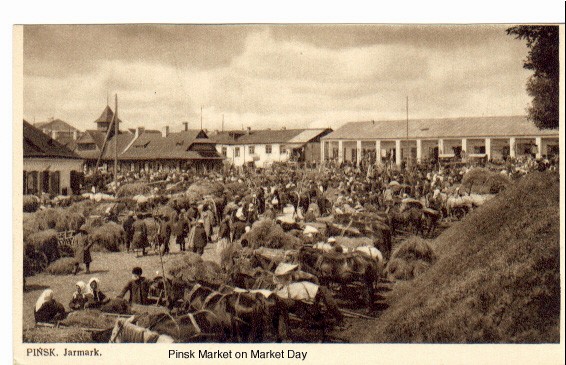

were prominent as traders in the market-place, also as landowners,

leaseholders, and farmers of taxes. In a document of March 27, 1522,

reference is made to the fact that Lezer Markovich and Avram

Volchkovich owned stores in the market-place near the castle. In

another document, dated 1533, Avram Markovich was awarded by the city

court the possession of the estate of Boyar Fedka Volodkevich, who had

mortgaged it to Avram's father, Mark Yeskovich. Still other documents

show that in 1540 Aaron Ilich Khoroshenki of Grodno inherited some

property in Pinsk, and that in 1542 Queen Bona confirmed the Jews

Kherson and Nahum Abramovich in the possession of the estate, in the

village of Krainovichi, waywodeship of Pinsk, which they had inherited

from their father, Abram Ryzhkevich.

Abram Ryzhkevich was a prominent member of the Jewish community at the

beginning of the sixteenth century, and was active in communal work.

He was a favorite of Prince Feodor Yaroslavich, who presented him with

the estate in question with all its dependencies and serfs. The

last-named wererelieved from the payment of any crown taxes, and were

to serve Abram Ryzhkevich exclusively. He and his children were

regarded as boyars, and shared the privileges and duties of that

class.

Pesak? Yesofovich.

Pesak? Yesofovich, mentioned with Yesko Meyerovich and Abram

Ryzhkevich in the grant to the Jewish community of 1506, took an

important part in local affairs. Like Abram Ryzhkevich, he was

intimate with Prince Feodor Yaroslavich, was presented by the prince

with a mansion in the town of Pinsk, and was exempted at the same time

from the payment of any taxes or the rendering of local services, with

the exception of participation in the repairing of the city walls. The

possession of this mansion was confirmed by Queen Bona to Pesak?'s son

Nahum in 1550, he having purchased it from Bentz Misevich, to whom the

property was sold by Nahum's father. Inheriting their father's

influence, Nahum and his brother Israel played important rôles as

merchants and leaseholders. Thus on June 23, 1550, they, together with

Goshka Moshkevich, were awarded by Queen Bona the lease of the customs

and inns of Pinsk, Kletzk, and Gorodetzk for a term of three years,

and had the lease renewed in 1553 for a further term of three years,

on payment of 875 kop groschen and of 25 stones of wax. In the same

year these leaseholders are mentioned in a characteristic lawsuit.

There was an old custom, known as "kanuny," on the strength of which

the archbishop was entitled to brew mead and beer six times annually

without payment of taxes. The Pesakhovich family evidently refused to

recognize the validity of this privilege and endeavored to collect the

taxes. The case was carried to the courts, but the bishop being unable

to show any documents in support of his claim, and admitting that it

was merely based on custom, the queen decided that the legal validity

of the custom should not be recognized; but since the income of the

"kanuny" was collected for the benefit of the Church the tax-farmers

were required to give annually to the archbishop 9 stones of wax for

candles," not as a tax, but merely as a mark of our kindly intention

toward God's churches."

The Pesakhovich Family.

The Pesakhovich family continues to be mentioned prominently in a

large number of documents, some of them dated in the late sixties of

the sixteenth century. Thus in a document of May 19, 1555, Nahum

Pesakhovich, as representative of all the Jews in the grand duchy of

Lithuania, lodged a complaint with the king against the magistrate and

burghers of Kiev because, contrary to the old-established custom, they

had prohibited the Jews from coming to Kiev for trading in the city

stores, and compelled them to stop at, and to sell their wares in, the

city market recently erected by the burghers. Postponing his final

decision until his return to Poland, the king granted the Jews the

right to carry on trade as theretofore.

In a document of Oct. 31, 1558, it is stated that the customs, inns,

breweries, and ferries of Pinsk, which had been leased to Nahum and

Israel Pesakhovich for 450 kop groschen, were now awarded to Khaim

Rubinovich for the annual sum of 550 groschen. This indicates that the

Pesakhovich family was yielding to the competition of younger men.

An interesting light is shed on contemporary conditions by a document

dated Dec. 12, 1561. This contains the complaint of Nahum Pesakhovich

against Grigori Grichin, the estate-owner in the district of Pinsk,

who had mortgaged to him, to secure a debt of 33 kop groschen and of 5

pails of unfermented mead, six of his men in the village of Poryechye,

but had given him only five men. The men thus mortgaged to Nahum

Pesakhovich were each compelled to pay annually to the latter 20

groschen, one barrel of oats, and a load of hay; they served him one

day in every seven, and assisted him at harvest-time. This would

indicate that the Jews, like the boyars, commanded the services of the

serfs, and could hold them under mortgage. In another document, dated

1565, Nahum Pesakhovich informed the authorities that he had lost in

the house of the burgher Kimich 10 kop groschen and a case containing

his seal with his coat of arms.

The Pinsk Jewry in 1555.

In 1551 Pinsk is mentioned among the communities whose Jews were freed

from the payment of the special tax called "serebschizna." In 1552-55

the starost of Pinsk took a census of the district in order to

ascertain the value of property which was held in the district of

Queen Bona. In the data thus secured the Jewish house-owners in Pinsk

and the Jewish landowners in its vicinity are mentioned. It appears

from this census that Jews owned property and lived on the following

streets: Dymiskovskaya (along the river), Stephanovskaya ulitza

(beyond the Troitzki bridge), Velikaya ulitza from the Spasskiya

gates, Kovalskaya, Grodetz, and Zhidovskaya ulitzi, and the street

near the Spass Church. The largest and most prominent Jewish

property-owners in Pinsk and vicinity were the members of the

Pesakhovich family—Nahum, Mariana, Israel, Kusko, Rakhval (probably

Jerahmeel), Mosko, and Lezer Nahumovich; other prominent

property-owners were Ilia Moiseyevich, Nosko Moiseyevich, Abram

Markovich, and Lezer Markovich. The synagogue and the house of the

cantor were situated in the Zhidovskaya ulitza. Jewish settlements

near the village of Kustzich are mentioned.

A number of documents dated 1561 refer in various connections to the

Jews of Pinsk. Thus one of March 10, 1561, contains a complaint of Pan

Andrei Okhrenski, representative of Prince Nikolai Radziwill, and of

the Jew Mikhel against Matvei Voitekhovich, estate-owner in the

district of Pinsk; the last-named had sent a number of his men to the

potash-works belonging to Prince Radziwill and managed by the Jew

above-mentioned. These men attacked the works, damaging the premises,

driving off the laborers, and committing many thefts.

By a decree promulgated May 2, 1561, King Sigismund August appointed

Stanislav Dovorino as superior judge of Pinsk and Kobrin, and placed

all the Jews of Pinsk and of the neighboring villages under his

jurisdiction, and their associates were ordered to turn over the

magazines and stores to the magistrate and burghers of Pinsk. In

August of the same year the salt monopoly of Pinsk was awarded to the

Jews Khemiya and Abram Rubinovich.But on Dec. 25, 1564, the leases

were awarded to the Jews Vaska Medenchich and Gershon Avramovich, who

offered the king 20 kop groschen more than was paid by the Christian

merchants. In the following year the income of Pinsk was leased to the

Jew David Shmerlevich.

In the census of Pinsk taken again in 1566, Jewish house-owners are

found on streets not mentioned in the previous census; among these

were the Stara, Lyshkovska, and Sochivchinskaya ulitzy. Among the

house-owners not previously mentioned were Zelman, doctor ("doctor,"

meaning "rabbi" or "dayyan"), Meïr Moiseyevia, doctor, Novach, doctor,

and others. The Pesakhovich family was still prominent among the

landowners.

Under Stephen Bathori.

In a circular letter of 1578 King Stephen Bathori informed the Jews of

the town and district of Pinsk that because of their failure to pay

their taxes in gold, and because of their indebtedness, he would send

to them the nobleman Mikolai Kindei with instructions to collect the

sum due. By an order of Jan. 20, 1581, King Stephen Bathori granted

the Magdeburg Rights to the city of Pinsk. This provided that Jews who

had recently acquired houses in the town were to pay the same taxes as

the Christian householders. Thenceforward, however, the Jews were

forbidden, under penalty of confiscation, to buy houses or to acquire

them in any other way. Elsewhere in the same document the citizens of

Pinsk are given permission to build a town hall in the market-place,

and for this purpose the Jewish shops were to be torn down. The grant

of the Magdeburg Rights was subsequently confirmed by Sigismund III.

(1589-1623), Ladislaus IV. (1633), and John Casimir (1650).

In spite of the growing competition of the Christian merchants, the

Jews must have carried on a considerable import and export trade, as

is shown by the custom-house records of Brest-Litovsk. Among those who

exported goods from Pinsk to Lublin in 1583 Levko Bendetovich is

mentioned (wax and skins), and among the importers was one ?ayyim

Itzkhakovich (steel, cloth, iron, scythes, prunes, onion-seed, and

girdles). Abraham Zroilevich imported caps, Hungarian knives, velvet

girdles, linen from Glogau, nuts, prunes, lead, nails, needles, pins,

and ribbons. Abraham Meyerovich imported wine. Other importers were

Abram Yaknovich, Yatzko Nosanovich, Yakub Aronovich, and Hilel and

Rubin Lazarevich.

About 1620 the Lithuanian Council was organized, of which Pinsk, with

Brest-Litovsk and Grodno, became a part. In 1640 the Jews Jacob

Rabinovich and Mordecai-Shmoilo Izavelevich applied in their own name,

and in the names of all the Jews then living on church lands, to

Pakhomi Oranski, the Bishop of Pinsk and Turov, for permission to

remit all taxes directly to him instead of to the parish priests.

Complying with this request, the bishop reaffirmed the rights

previously granted to the Jews; they were at liberty to build houses

on their lots, to rent them to newly arrived people, to build inns,

breweries, etc.

Increasing Anti-Jewish Feeling.

Toward the middle of the seventeenth century the Jews of Pinsk began

to feel more and more the animosity of their Christian neighbors; and

this was true also of other Jewish communities. In 1647 "Lady" Deborah

Lezerova and her son "Sir" Yakub Lezerovich complained to the

magistrates that their grain and hay had been set on fire by peasants.

In the following year numerous complaints of attack, robbery, plunder,

and arson were reported by the local Jews. Rebellion was in the air,

and with the other Jewish communities in Lithuania that of Pinsk felt

the cruelties of the advancing Cossacks, who killed in great numbers

the poorer Jews who were not able to escape. Prince Radziwill, who

hastened to the relief of the city, finding the rioters there, set it

on fire and destroyed it.

Hannover, in "Yewen Me?ulah," relates that the Jews who remained in

Pinsk and those who were found on the roads or in the suburbs of that

city were all killed by the Cossacks. He remarks also that when

Radziwill set fire to the town, many of the Cossacks endeavored to

escape by boats and were drowned in the river, while others were

killed or burned by the Lithuanian soldiers. Meïr ben Samuel, in "Zuk

ha-'Ittim," says that the Jews of Pinsk were delivered by the

townspeople (i.e., the Greek Orthodox) to the Cossacks, who massacred

them.

Evidently Jews had again appeared in Pinsk by 1651, for the rural

judge Dadzibog Markeisch, in his will, reminds his wife of his debt of

300 gulden to the Pinsk Jew Gosher Abramovich, of which he had already

repaid 100 gulden and 110 thalers, and asks her to pay the remainder.

In 1662 the Jews of Pinsk were relieved by John Casimir of the

headtax, which they were unable to pay on account of their

impoverished condition. On April 11, 1665, the heirs of the Jew Nathan

Lezerovich were awarded by the court their claim against Pana

Terletzkaya for 69,209 zlot. For her refusal to allow the collection

of the sum as ordered by the court she was expelled from the country.

In 1665, after the country had been ruined by the enemy, the Jewish

community of Pinsk paid its proportion of special taxation for the

benefit of the nobility.

In the Nineteenth Century.

Beyond the fact that ?asidism developed in the suburb of Karlin (see

Aaron ben Jacob of Karlin), little is known about the history of the

Pinsk community in the eighteenth century; but since the first quarter

of the nineteenth century the Jews there have taken an active part in

the development of the export and import trade, especially with Kiev,

Krementchug, and Yekaterinoslav, with which it is connected by a

steamship line on the Dnieper. Many of the members of the Jewish

community of Pinsk removed to the newly opened South-Russian province

and became active members of the various communities there. In the

last quarter of the nineteenth century prominent Jewish citizens of

Pinsk developed to a considerable extent its industries, in which

thousands of Jewish workers now find steady occupation. They have

established chemical-factories, sawmills, a match-factory (400 Jewish

workers, producing 10,000,000 boxes of matches perannum; established

by L. Hirschmanin 1900), shoe-nail factory (200 Jewish workers),

candle-factory, cork-factory, parquet-factory, brewery, and

tobacco-factories (with a total of 800 Jewish workers). The Luries and

Levines have been especially active in that direction. Another

cork-factory, owned by a Christian, employs 150 Jewish workers; and

the shipyards (owned by a Frenchman), in which large steamers and

sailing vessels are built, also employs a few hundred Jews. Besides

these, there are many Jewish artisans in Pinsk who are occupied as

nailsmiths, founders, workers in brass, and tanners; in

soap-manufactories, small breweries, violin-string factories, the

molasses-factory, the flaxseed-oil factory, and the ?allit-factory. In

all these the Jewish Sabbath and holy days are strictly observed. Many

Jewish laborers are employed on the docks of Pinsk and as skilled

boatmen.

Pinsk has become one of the chief centers of Jewish industry in

northwest Russia. The total output of its Jewish factories is valued

at two and a half million rubles. The pay of working men per week in

the factories is:

see table

Since 1890 there have been technical classes connected with the Pinsk

Talmud Torah, where the boys learn the trades of locksmiths,

carpenters, etc., and technology, natural history, and drawing.

Bibliography: Regesty i Nadpisi;

Russko-Yevreiski Arkhiv. vols. i. and ii.;

Voskhod, Oct., 1901, p. 23;

Welt, 1898, No. 11.J. G. L.

Rabbis.

The first rabbi mentioned in connection with Pinsk is R. Simson. With

R. Solomon Luria (MaHRaSh) and R. Mordecai of Tiktin, he was chosen,

in 1568, to adjudicate the controversy relating to the association of

Podlasye. His successors were: R. Naphtali, son of R. Isaac Katz

(removed to Lublin; d. 1650); R. Moses, son of R. Israel Jacob (c.

1673; his name occurs in the "Sha'are Shamayim"); R. Naphtali, son of

R. Isaac Ginsburg (d. 1687); R. Samuel Halpern, son of R. Isaac

Halpern (d. 1703; mentioned in "Dibre ?akamim," 1691); R. Isaac Meïr,

son of R. Jonah ?e'omim; R. Samuel, son of R. Naphtali Herz Ginzburg

(mentioned in "'Ammude 'Olam," Amsterdam, 1713); R. Asher Ginzburg

(mentioned in the preface to "Ga'on Lewi"); R. Israel Isher, son of R.

Abraham Mamri (mentioned in Tanna debe Eliyahu, 1747); R. Raphael, son

of R. Jekuthiel Süssel (1763 to 1773; d. 1804); R. Abraham, son of R.

Solomon (mentioned in the "Netib ha-Yashar"); R. Levy Isaac; R.

Abigdor (had a controversy with the ?asidim on the question of giving

precedence in prayers to "Hodu" over "Baruk she-Amar"; the question

was submitted for settlement to Emperor Paul I.: "Voskhod," 1893, i.);

R. Joshua, son of Shalom (Phinehas Michael, "Masseket Nazir,"

Preface); R. ?ayyim ha-Kohen Rapoport (resigned in 1825 to go to

Jerusalem; d. 1840); Aaron of Pinsk (author of "Tosefot Aharon,"

Königsberg, 1858; d. 1842); R. Mordecai Sackheim (1843 to his death in

1853); R. Eleazar Moses Hurwitz (1860 to his death in 1895).

Among those members of the community of Pinsk who achieved distinction

were the following: R. Elijah, son of R. Moses ("?iryah Ne'emanah," p.

125); R. Moses Goldes, grandson of the author of "Tola'at Ya'a?ob"; R.

Kalonymus Kalman Ginzburg (president of the community); R. Jonathan

("Dibre Rab Meshallem"); R. Solomon Bachrach, son of R. Samuel

Bachrach ("Pin?as Tiktin"); R. ?ayyim of Karlin ("'Ir Wilna," p. 31);

R. Solomon, son of R. Asher ("Geburath He-Or"); R. Joseph Janower

("Zeker Yehosef," Warsaw, 1860); R. Samuel, son of Moses Levin ("Ba'al

?edoshim," p. 210); R. Asher, son of R. Kalonymus Kalman Ginzburg

("?iryah Ne'emanah," p. 185); R. Gad Asher, son of R. Joshua Rokea?

("Anshe Shem," p. 63); R. Joshua Ezekiel (ib.); R. ?ayyim Schönfinkel

(ib. p. 70); R. Abraham Isaac ("Birkat Rosh"); R. Notel Michael

Schönfinkel ("Da'at ?edoshim," p. 181); Zeeb, Moses, Issac, and

Solomon Wolf, sons of R. Samuel Levin; R. Jacob Sim?ah Wolfsohn

("Anshe Shem," p. 40); R. Aaron Luria; R. Samuel Radinkovitz.

The writers of Pinsk include: R. Moses Aaron Schatzkes (author of

"Maftea?"), R. ?ebi Hirsch, Shereshevski, A. B. Dobsevage, N. M.

Schaikewitz, Baruch Epstein, E. D. Lifshitz. Abraham Kunki passed

through Pinsk while traveling to collect money for the support of the

Jerusalem Talmud Torah (preface to "Aba? Soferim," Amsterdam, 1704).

In 1781 the heads of the Jewish congregations of Pinsk followed the

example of some Russian Jewish communities by excommunicating the

?asidim. In 1799 the town was destroyed by fire, and its records were

lost. Pinsk has two cemeteries: in the older, interments ceased in

1810. The total population of the town (1905) is about 28,000, of whom

18,000 are Jews.

Karlin:

Until about one hundred years ago Karlin was a suburb of Pinsk, and

its Jewish residents constituted a part of the Pinsk community. Then

R. Samuel Levin obtained the separation of Karlin from Pinsk

(Steinschneider, "'Ir Wilna," p. 188). In 1870 the ?asidim of Karlin

removed to the neighboring town of Stolin. The rabbis of the

Mitnaggedim of Karlin include: R. Samuel Antipoler; R. Abraham

Rosenkranz; the "Rabbi of Wolpe" (his proper name is unknown); R.

Jacob (author of "Miskenot Ya'a?ob") and his brother R. Isaac (author

of "?eren Orah"); R. Samuel Abigdor Tosefa'ah (author of "She'elot

u-Teshubot"); David Friedmann (the present [1905] incumbent; author of

"Yad Dawid").H. R. B. Ei.

--------------------------------------

Pinsk

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Pinsk is first mentioned in the chronicles of 1097 as Pinesk, a town

belonging to Sviatopolk of Turov. The name is derived from the river

Pina. Pinsk's early history is closely linked with the history of

Turov. Until the mid-12th century Pinsk was the seat of Sviatopolk's

descendants, but a cadet line of the same family established their own

seat at Pinsk after the Mongol invasion of Rus in 1239.

The Pinsk principality had an important strategic location, between

the principalities of Navahrudak and Halych-Volynia, which fought each

other for other Ruthenian territories. Pinsk did not take part in this

struggle, although it was inclined towards the princes of Novaharodak,

which is shown by the fact that the future prince of Novaharodak and

Vaisvilkas of Lithuania spent some time in Pinsk.

In 1320 Pinsk was won by the rulers of Navahrudak, who incorporated it

into their state, known as the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. From this

time on Pinsk was ruled by Gedimin's eldest son, Narymunt. Afterwards,

for the next two centuries the city had different rulers.

In 1581 Pinsk was granted the Magdeburg rights and in 1569, after the

union of Lithuania with the Crown of the Polish Kingdom, it became the

seat of the province of Brest.

From 1633 on Pinsk had a secondary school, a so-called brotherhood

school (the brotherhoods were religious citizens' organisations with

the aim of providing education for their members and their children).

During the Cossack rebellion of Bohdan Chmielnicki (1640), it was

captured by Cossacks who carried out a pogrom against the city's

Jewish population; the Poles retook it by assault, killing 24,000

persons and burning 5,000 houses. Eight years later the town was

burned by the Russians.

In 1648, on the eve of the Russo-Polish War (1654-1667), Pinsk was

occupied by Ukrainian Cossack army under commander Niababy and could

only be reconquered with great difficulty by prince Janusz Radziwill,

a high-ranking commander in the Polish-Lithuanian army. During the war

between Moscow and Poland-Lithuania (1654-1667) the city suffered

heavily from the attacks of the Muscovite army under Prince Volkolnsky

and its allied army of Ukrainian Cossacks.

Charles XII took it in 1706, and burned the town with its suburbs. In

spite of all the wars the city recovered and the town developed with

the existence of a printing workshop in Pinsk from 1729-44.

Pinsk fell to the Russian Empire in 1793 in the Third Partition of

Poland, became part of Poland in 1920 after the Polish-Soviet War and

was incorporated into Soviet Union in 1939. At this time, the city's

population was over 90% Jewish. From 1941 to 1944 it was occupied by

Nazi Germany, and its Jewish population interned in concentration

camps. Between 18,000 and 30,000 Jewish residents of Pinsk were killed

by the Nazis in the Holocaust. Ten thousand were murdered in one day.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 Pinsk has belonged to

the Republic of Belarus.

--------------------------------------------

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Pinsk massacre was the murder of thirty-five Jewish residents of

Pinsk taken as hostages by the Polish Army after it captured the city

in April 1919, during the opening phases of the Polish-Soviet War. The

local Jews were arrested while holding a meeting. The Polish officer

in charge, stating that the meeting was a Bolshevik gathering, ordered

the execution of the suspects without trial. His decision was defended

by his Polish military superiors, but widely criticized by

international public opinion.

On April 5th, after the Polish army had occupied Pinsk, some

seventy-five Jewish civilians were participating in a meeting; sources

vary on whether they had obtained permission to do so from the Polish

garrison commander (Major Luczynski)[1] or whether the meeting was not

explicitly authorized.[2] Norman Davies notes that "the nature of the

illegal meeting, variously described as a Bolshevik cell, an assembly

of the local co-operative society, and a meeting of the Committee for

American Relief, was never clarified".[2] The meeting was terminated

and its participants were taken hostage by Polish soldiers, who

believed that the Jews were having a meeting in support of the

Bolsheviks (at that time the entire region was witnessing the

beginning of the Polish-Soviet War and Bolshevik forces were near the

city).[1] [2]

A Polish lieutenant,[3] after hearing rumours that the Jewish

inhabitants of the town, who comprised the majority of the residents

of Pinsk, were preparing to riot, panicked and, instead of carrying

out a further investigation, ordered the execution of the hostages in

order to make an example of them.[2] Within an hour of the arrest,

thirty-five [1][3][4] of the detainees were shot by Polish

soldiers.[4] Norman Davies notes that "most of the victims were

Jewish".[2] The next morning three wounded victims found to be still

alive and were killed by the Poles.[5]

A few days later Jewish population of the city was fined by Polish

military authorities at Pinsk. Fine was 100,000 marks, the same amount

that had been received by Jewish Relief Committee at Pinsk shortly

before[6]

Reactions

Polish army

The Polish Group Commander General Antoni Listowski claimed that the

gathering was a Bolshevik meeting and that the Jewish population

attacked the Polish troops.[5] The overall tension of the military

campaign was brought up as a justification for the crime.[7] The

Polish military refused to give investigators access to documents, and

the officers and soldiers were never punished. Major Luczynski was not

charged for any wrongdoing and was eventually transferred and promoted

reaching the rank of colonel (1919) and general (1924) in the Polish

army.[8] The events were criticized in the Sejm (Polish parliament),

but representatives of the Polish army denied any wrongdoing.[4]

International

In the Western press of the time, the massacre was referred to as the

Polish Pogrom at Pinsk,[9] and was noticed by wider public opinion.

Upon a request of Polish authorities to president Wilson, an American

mission was sent to Poland to investigate nature of the alleged

atrocities. [10] The mission, led by Henry Morgenthau, Sr., published

the Morgenthau Report on October 3, 1919. [5] [11] According to the

findings of this commission, a total of about 300 Jews lost their

lives in this and related incidents. The commission also severely

criticized the actions of Major Luczynski and his superiors with

regards to handling of the events in Pinsk.[5] [11] However the

Morgenthau commission also found out that the Polish military and

civil authorities did do their best to prevent the incidents and their

recurrence in the future; according to Morgenthau the excesses were

"political as well as anti-Semitic in character". [11] [12]

Commemoration

In 1926, kibbutz Gevat (Gvat) was established by emigrants from Pinsk

to the British Mandate of Palestine in commemoration of the Pinsk

massacre victims.

(Then click your browser's "Back" button to return here.)

This is a multiple-database search, which incorporates the databases containing over 300,000 entries from Belarus. This multiple database search facility incorporates all of the following databases: JewishGen Family Finder (JGFF), JewishGen Online Worldwide Burial Registry (JOWBR), JRI -Poland, Yizkor Book Necrologies, Belarus Names Database, Revision Lists, and much more!

Click the button to show all entries for Pinsk in the JewishGen Belarus Database.

|

Updated by BAE, July 2018 Copyright © 2008 Eilat Gordin Levitan and Kevin Chun Hoi Lo |

This site is hosted at no cost by JewishGen, Inc., the Home of Jewish Genealogy. If you have been aided in your research by this site and wish to further our mission of preserving our history for future generations, your JewishGen-erosity is greatly appreciated.