Sixty years after William Schwartz went to Miskolc, his niece Helene Kenvin (Adolf Schwartz’s granddaughter, great-granddaughter of Farkas Schwartz) and her husband Howard traveled to Hungary. Prior to their departure, the Kenvins had arranged for a company in Budapest to take them on a one-day trip to Miskolc. These excerpts are from Helene’s journal of their trip.

Route from Budapest to Miskolc

We had breakfast delivered to our room around 6AM. Peter Langh and Joseph Kiss picked us up at seven -- Peter to drive and Joseph to translate. Peter had a very small car into which we two tall Americans were stuffed for more than three uncomfortable hours on the road to Miskolc.

Along the way, Joseph looked at the copies of family records I’d brought with me. He told me that the death record for my great-grandfather Farkas Schwartz noted that he had been a tailor (“szabo”); but he could not read the word preceding it. I had an 1848 census record for a Jacob Weiss, which gave his town of birth; but Jacob Weiss was a common name and I was not sure that it was our Jacob Weiss, father of Grandpa’s mother Celia Weiss Schwartz.

What excitement I felt when we came to the outskirts of the town and saw the signpost “MISKOLC.” Naturally, we had to take some photos to mark the occasion [photo left].

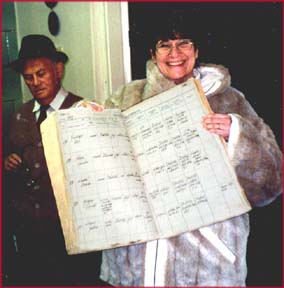

The first thing we did upon arrival in Miskolc was go to the Jewish cemetery on Avas Hill. We found the caretaker [photo right] and, at our request, he brought out a huge register showing where everyone had been buried. I took one look at it and my heart sank: the earliest entry was 1905 and my great-grandfather Farkas had died in 1891.

I was heartbroken. There was no point in trying to look for the grave-site, as I had been told that when Farkas had died, his wife Celia had been too poor to put up a gravestone. In Uncle Bill’s 1937 letter, he had described how the then-caretaker had found the grave-site in the cemetery records; but those old records no longer were at the cemetery and might have been lost or destroyed during the war. This was a tremendous disappointment for us, as a primary purpose of our journey to Miskolc had been to locate the grave-site of my great-grandfather and arrange to have a stone erected over it. Now that would be impossible.

Saddened and downcast, I stood in the middle of the cemetery with my head drooping. When I looked up, I realized that I was standing right in front of the grave of Adolf Strausz and Roza Adler -- the great-grandparents of my fellow genealogist Julie Kirsh. I began to laugh. Well, at least I’d found something, so the cemetery visit was not a total loss. I took photos of the graves for Julie and felt a bit better. Howard told me that he had heard a voice say to him, “Don’t worry, it doesn’t matter.” I knew he was pretending to have “heard” from Great-grandpa Farkas, to lessen my feeling of sadness. Strangely enough, it worked.

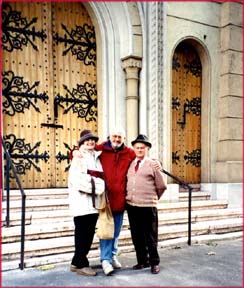

We then went to a big synagogue on Kazinczy utca (Kazinczy Street). We met the shammas, Mr. Beres [photo left] who, when questioned, said he didn’t know anything about old cemetery records. He tried to call the president of the synagogue, but there was no answer. The shammas then gestured to the next room and, though it was dark, I could see piles of old registers on a big table -- three or four dozen books, in various states of deterioration.

I looked at them longingly, wondering whether the missing marriage certificate of my great-grandparents Farkas and Celia or the birth certificate of their daughter Jenny might be somewhere before me. There was no time to go through them. Had I known of their existence, I would have planned to spend more than a day in Miskolc, so that I could examine them thoroughly and make copies of relevant records that I found.

I picked up a book at random, flipped a few pages --- and found myself looking at the death record of my great-grandpa Farkas Schwartz. I already had a copy of the LDS microfilm of the record; but to pick up the right book out of dozens and find the original entry in the Miskolc synagogue was an amazing experience. Howard took a photograph of me holding the book and grinning with happiness [photo right].

Unfortunately, it was not the cemetery register that we needed to find the grave. Even so, we did learn something from it: Joseph was able to read the word he could not decipher on the photocopy of the microfilm. We now knew that at the time of his death, Farkas Schwartz had been a “retired” tailor.

We walked into the chapel, which had been built in 1863 and was sadly in need of repair. Howie said that it must have been beautiful when it was new. When this remark was translated, Mr. Beres murmured, “It was beautiful when it was full.”

His comment was a poignant and sad reminder that the present Jewish community only numbered 250 elderly people (he told us that about 24 people come to services each Shabbat) and that the vast majority of the thousands of pre-war residents of Miskolc had been murdered during the war. Mr. Beres himself was a survivor of a Russian labor camp. Howard gave him the kipah we had brought from home, which he had planned to wear had we been able to say kaddish at my great-grandfather’s grave.

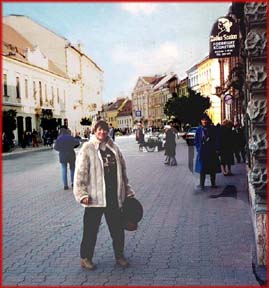

We stopped at a used book store and I bought a small book on Miskolc. Then we had a middling lunch at a place called “John Bull Pub,” which we agreed was a bizarre place to be eating in Miskolc. After lunch, we walked around the main street [photo left] for a while and I found three old postcards of the town.

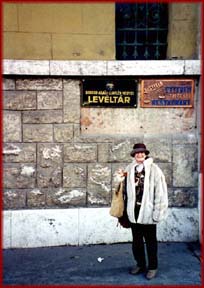

Then we went to the Borsod county archive [photo right], where the staff helped me to find graphics showing how Miskolc had looked when the Schwartz, Weiss, and Balajti families had lived there in the 19th century. We spent about an hour in the archive. Fragile old books were brought to me and, with the permission of the archive’s staff, I used my special lenses to make photographs of some of the graphics in them.

Prior to our trip, I had sent an email to Peter Langh in which I had told him that I knew from my Uncle Bill’s 1937 letter that our family had lived at 23 St. Peter’s Gate or Szentpeteri Kapu 23 in Hungarian. Peter had sent me a dismaying reply: that the old houses along that street all had been razed in the 1950s and had been replaced by Soviet-style apartment buildings. He doubted that I would find our ancestral home on St. Peter’s Gate.

I had been discouraged to hear this, especially as the photos that Uncle Bill had taken in Miskolc either did not turn out or had been lost. Even so, when we left the archive, I told Peter that I wanted to go to St. Peter’s Gate. At the least, I could take a photo of the street sign and the site where my great-grandparents' house used to be.

St. Peter’s Gate was a wide boulevard that went from the north to south end of the city. When we approached it from the left, we could see that the entire far side was covered with three or four story buildings that obviously had been built within the last 40 or 50 years. We turned onto St. Peter’s Gate and, to our surprise, on the left side of the street --- facing the sea of apartment buildings --- were about half-a-dozen old houses. We looked at the house numbers as we drove up St. Peter’s Gate: 17 ... 19 ... 21 ... 23!!!

There was the house in which Farkas and Celia Schwartz had lived with their children Jennie and (my paternal grandfather) Adolf! After the big disappointment of our failure to find Farkas’s grave, this was especially gratifying. None of us could believe it and we all laughed with glee. I jumped out of the car and began taking pictures [see below].

The wooden gate in the six-foot high concrete wall surrounding the courtyard was locked and no one appeared to be living in the house. Joseph went into surrounding buildings and a store that was on the ground floor of the side of the house facing the street. He was trying to get a key to the gate, so that we could go into the courtyard; but he had no success.

I peered through the slats of the gate into the courtyard, but could not see much. Although it was likely that the interior of the old house had been renovated, the shell of the building was the same as it had been more than 100 years ago, when our family had lived in it. Joseph confirmed this from a neighbor, who also told him that “23” always had been the number of that particular building.

Finding the house was an unexpected thrill and a great way to end the day. Even Howard, whose eyes tend to glaze over with boredom when I mention genealogy, admitted that our trek to Miskolc had been a fascinating highlight of our trip to Hungary.

|

|  |

Street sign at St. Peter's Gate and views of the house in which Farkas Schwartz lived.

Upon her return from Miskolc in 1997, Helene Kenvin tried to interest several Jewish archives and individuals in acquiring the vital-records registers from the Kazinczy utca synagogue, without success. The current condition and disposition of these registers is not known.

Credits: Photos, graphics, text, and page design copyrighted © 2008 by Helene Kenvin. Page created by Helene Kenvin. All rights reserved.