Lublin, Poland

Avraham Cwi Majzels

With thanks to Dan Oren, his grandson, who provided the image and article.

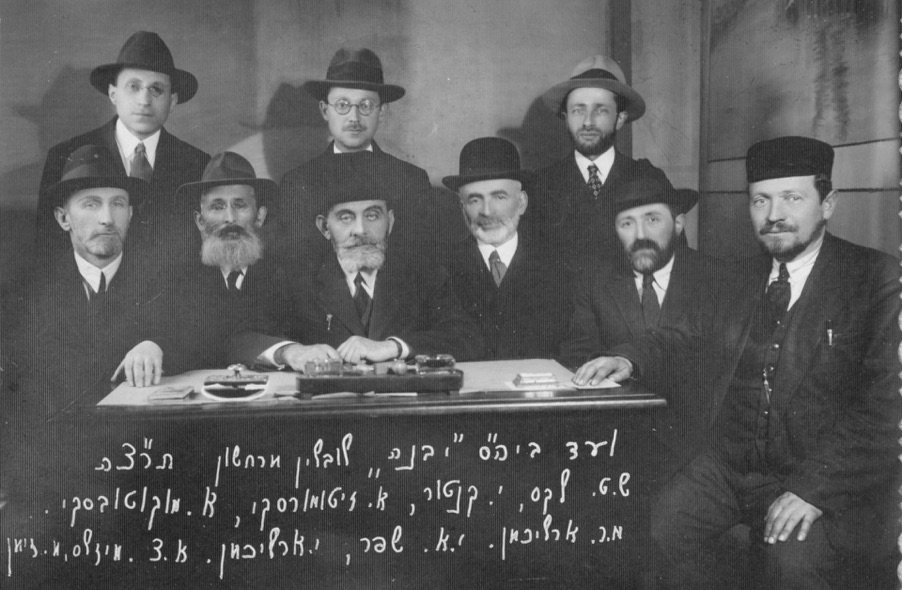

1934 photo of the board (the Va’ad) of the Yavneh School in Lublin.

Dan Oren’s grandfather A. C. Majzels is in the middle of the top row.

The other people in the photo are identified by name.

“Dos Gesl”, The Alley

by Avraham Cwi Majzels, from the Encyclopedia of the Diaspora: Lublin,

published 1957 in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, pages 268-274.

Translation into English by Rebeka (Majzels) Oren (ACM’s daughter) and Dan Oren (RO’s son)

Until the eve of the First World War there were Jews of Lublin who lived in the environment of a special neighborhood that went by the name "the Jewish quarter." The walls of the neighborhood had started to crumble quite a few years before that. But only a few Jews opened shop in the Christian neighborhood; the few that did move their domiciles were mainly among the group of the intelligentsia and the degree-holders, such as doctors and lawyers and their like. And even then, most of the Jewish doctors remained among their own people in the Jewish quarter.

The masses of the Jewish people that dwelt in the Jewish section almost did not leave its borders. They did not come in contact with their Christian neighbors and conducted their affairs and lives following the purity of the tradition. Except for the intelligentsia and the college-educated, most of the Jews wore their traditional garb: the kapotah, and on their heads "the Jewish hat." The language of their discourse was Yiddish. The Shabbat ruled supreme in the Jewish neighborhood. At dusk on the eve of Friday night, as the Shamash [community religious aide] announced that the time of candle-lighting was near, all the shops would close automatically, and one and all rushed to their homes to welcome the Shabbat.

Even the streets in the neighborhood where the Jews lived, they called by special names of their own without even knowing what their official name was. Sometimes it was a literal translation from the Polish like "Podzamcze" which they called "Hintern schloss," which meant "Behind the castle" or "Jateczna" which was "Di Yatke Gas," which meant "The Street of the Butchers." At times the translation was faulty, like "Ruska Street" (the Russian Street) which they would call "D'reisha," [meaning "the Evil"]. But sometimes there was no relation between the formal name and the name that was used by the Jews. For example, the wide street "Szeroka" they called "Yidn Gas," (Jewish Street). And many of the Jews in Lublin didn't even know that "The Alley," ("Dos Gesl") was actually "Nadstawna" street, (Lake Street). For them it was called "The Alley."

It is about this alley, in which every Jewish child made his first inroads in the study of Torah, that I would like to tell.

The Alley was located in the heart of Jewish Lublin and was not considered among the big streets. As its name indicates, it was just an alley. On one side it bordered the Jewish market. There were two markets in the Jewish Quarter—the "Polish Market” that continued along "Nowa" street until the town clock, and the “Jewish Market” that was located in the middle of Lubartowska street close to the river which divides the street. Why was one was called the Polish market and the other the Jewish market? Perhaps the answer is because the first one was located in the Christian neighborhood and most of the butcher shops were run by Christians, while the second market found itself in the Jewish section where only Jewish butchers sold kosher meat. The villagers that used to bring their produce and poultry daily to the two markets were beautifully versed in the Jewish traditions and knew to supply the proper needs for every season of the calendar. Before Yom Kippur—chickens for Kapparot, before Pesach, eggs, chickens, etc.

Between the market and the alley a narrow river cut across where the women used to do their laundry. On the second side of the alley was a narrow street named "Dos Apteyk Gesl" (the Pharmacy Alley). And that constituted a passage between the houses on Cyrulnicza street (Street of the Barber-Surgeons) and the Jewish Street [Szeroka], where on one side was the synagogue of the boiler-makers (Di Kettler Shul). On the other side was the pharmacy, well known by its name, "The Jewish Pharmacy,"—although its owners were never Jews.

All the boys and girls (because the girls were also taught in the Cheders) were brought to the alley from the age of three in order to learn the Alef-Bet (alphabet) from the teachers. Here were found all kinds of Cheders: cheders for toddlers, cheders for learning Torah, and cheders for Gemarah.

At the Toddlers' Cheder, the little ones from age three studied the shape and form of the letters. And when they reached the age of five, they graduated to learning Chumash. And after two years there, they proceeded to learn Gemarah (in order to acquire the knowledge of the Tosafot). The teachers not only taught there, but they also lived there with their families.

The teachers divided the building in such a manner that the Toddlers’ teachers used the ground floor for the comfort and the security of the very young. After all, it is not easy to climb stairs and there is a danger of falling. The number of the children with the teachers was unlimited. They took in as many as they could. Even the dates for admission to these schools was not determined. Only whenever the child reached the age of three, the parents would enroll him into a Cheder and new children would join them almost daily. Each enrollment and first day of a child was accompanied by a party for the children. The mother would carry the child in her arms (and if she was young enough even grandmother would join) and all would partake of the custom where the mother would offer sweets for all the children of the Cheder.

In the lower grades usually two teaching assistants would help the instructor. The older one would help in teaching and would receive part of his salary from the instructor himself, and part from the parents. In most cases, it was a young scholar who actually had the intention of himself becoming an instructor and would assume full responsibility when the head instructor would retire. The second assistant was a young man whose duty was to bring the children to the Cheder and take them back home at the end of the day. In the winter when the slanted bridges over the river were covered with ice from spilled water from the buckets of the water-bearers and the crossings became dangerous for the children, the young man would carry them one by one on his shoulders and would bring them over to the other side of the river. These young men would get board at the children's parents, each day at a different home.

When Chanuka time would come, these young helpers would provide the children with dreidels, at Purim time groggers (noisemakers), at Simhat Torah flags, and they received in return payments from the parents. At Purim they served as messengers of Mishloach Manot [food gifts] from the instructors to the parents and from the parents to the instructors. That was the way they made their living.

The toddler's classes would last only during daylight hours. The older children in the Chumash (Torah) Cheders would even study in the evenings in winter and when they would return home, [the instructors or assistants] had to light their way with torches. Since the system was that the instructors would teach every child personally, most of the children would play outside and only from time to time would be called in to the assistant or the instructor for learning. The instructors were particularly on guard to make sure that when the inspectors would come to test the children that not too many children were together.

Free time for the children that learned from the Chumash-teachers was more constricted, for they were supposed to spend most of the daily hours in that Cheder. Also, in these Cheders, they had teaching assistants, who helped the teacher because here also the number of students was unlimited. Every visit of the inspector created a real panic. The teacher hastily stopped the lesson, commanded the children to disperse and instructed them not to reveal, chas v’Shalom (Gd forbid) where they were learning. Excited and fearful, the children ran down the stairs and not once during this frightened run were any injured.

In the Cheders for Chumash (Torah) there was not a need for the junior helpers because the children came and went home by themselves by now. Here there were already fixed vacation time: one after Sukkot (the Hebrew month of Cheshvan) and the second after Pesach (the Hebrew month of Iyyar).

During Chol Hamoed [the intermediate days] of Sukkot and Pesach the instructors would recruit new students to their Cheders. These periods determined their destiny and income for the next half of the year. The children didn’t learn while the teachers visited the homes of the parents. One could see in The Alley in the vacation time how the Chumash teachers and the toddlers walked the streets together and negotiated which instructor would receive which children from the previous year. The administrators of the toddler Cheders gave guidance directly to the parents about the Chumash-teachers, naturally about the wages of the teachers.

After the Torah Cheders, the children would graduate to the Gemarah teachers who would teach them Torah and Rashi and began teaching them the Gemarah. In this stage, they learned for two years. The instructors of Gemarah were not assisted by teaching assistants. The number of the children would be limited and every father would take a personal interest in the teacher and inquire about the number of students in the class. The maximum that was acceptable in those days was twelve children in a class, yet the teachers always took in an extra two or three students.

There were the three types of Cheders that were found in The Alley. Instructors on a higher echelon than Gemara and Tosefot were to be found all over the city, but always with a limited number of children.

Every Cheder had its own special celebrations and parties beyond those that were shared by all. As was said earlier, some of the mothers of the children in the toddler Cheders would bring candies for the first day of learning. The biggest party would take place when the child would start learning Chumash. This celebration would take place on a Shabbat when the child would reach the age of five (to fulfill the saying "At five to study the Bible.") [Pirke Avot 5:21]. This party was called the beginning of the Chumash. The anticipation for the celebration was great. The preparations by the parents and the child were made over a long time. The child would learn the first sentence of [the] Vayikra Torah portion by heart, in order to be prepared for questions from “the greeters.” (These were the children that the teacher had taught to offer questions from the biblical book of Vayikra [Leviticus].) And on the appointed Shabbat for the celebration in the afternoon hours invited guests gathered to hear from the mouth of the child a D'rasha [a lesson from the Chumash]. Also present were the teacher, the head of the cheder and a group of children from the Cheder. (The teacher refrained from bringing all the children from the cheder because he didn’t want the numbers to be too large. For each celebration he brought different children.) The young honoree would be stood on a table, dressed in a special kapote (coat) made from glossy silk or satin with a silk belt and a silk hat, looking like a young Chasid. The children “greeters” stood in front of him and started a dialogue between them. They posed questions to the young “bachur haChumash” (the student of the Torah) who had to answer them. At the end of the discourse candies were thrown above the head of the honoree and the rest of the children at the celebration would receive little candy bags, and the “greeters” received a double portion: two bags: one of gold color and the other of silver color.

In the other Cheders, in cheders for Chumash and Gemara, these kinds of parties didn’t occur; instead there was a festive meal at the time that the children completed their winter studies in the evenings before the holiday of Passover. Each child brought a few small coins [for charity] and the Rabbi's wife would prepare a meal with wine and cake. At the Cheders for Gemarah they prepared platters on a long table with fish and meat.

A general celebration, attended by all the cheders without exception, took place on Lag Ba’omer. A driver would travel with the children for a “krangl” (a trip outside the city). Every child would bring along a red hard-boiled egg (to obtain the color, the egg was boiled in water with onion peels). Each child also received a few small coins. The instructor would hire a horse-carriage, would load the children on it and stood on one side of the carriage, while the teacher’s assistant stood on the other in order to watch the children on the crowded carriage to be sure they wouldn’t fall from it. The children would leave town and there they ate their eggs, spent a little time, and returned to the city.

The alley included a few poor shops without numbers or signs, dark niches making it hard to know what they contained from outside. In these shops one would find a barrel of herrings, some loaves of bread, a sack of flour, some liters of sugar and a little kerosene. In one special place one would find cakes and all kinds of sweets laid out on tins. These shops made their living from what the children from the cheders would buy with their coins. But the poor shopkeepers had competition from the wives of the instructors, who themselves would try to lure the children to buy from the women instead of the poor shopkeepers. Outside of this, on the side of the Alley there stood tables on which were some sweets and cakes, and from here also the only buyers were the cheder children.

As a rule, it has to be said that the studies took place in one big room. In one corner the instructor sat with one group of kids. In the other corner, the teacher’s assistant.

The room also contained a few tables and benches for the children. On the wall there was the license of the school inspector authorizing the cheder and also a picture of Tsar Nicholas II. Several times a month a teacher would come to the cheder to teach Russian [language]. In these lessons, the children learned to sing the Russian anthem and the honorary titles of the Tsar and his family. Each time the inspector would visit the cheder, the instructor and children would recite out loud in unison the honorary titles and broke out singing the Russian anthem. This was the essence of the test for the children.

Before Passover the teaching assistants would engage in very honored work. Pairs of teaching assistants from the two kinds of cheders visited the housewives [in town] and brought with them mortars and pestles in order to grind the matzot to flour and crumbs [matzah meal]. This work was done in the evenings after the learning in the cheder. The housewives would set aside a special room [in their homes] where no chametz [leavened food material] could be found. The young men received payments for their work.

There was a special entrance from the alley to the courtyard of the rabbi of Lublin, Rabbi Avramele Eiger. In this courtyard was the new Beit Midrash [House of Learning] that was built not long ago and also the house of the rabbi. During the holidays, particularly Rosh Hashanah and Shavuot when Chasidim in the hundreds came to the rabbi from the neighboring villages, they would camp there in the alley if they could not afford hotels in town. And many residents would turn their homes into hostels. For the Chasidim this was the cheapest place to stay and also the most comfortable because it was close to the Rabbi’s Beit Midrash. On these special occasions The Alley was vibrantly alive with numerous Chasidim all dressed in their best fineries and their Shtreimlech [fur hats] on their heads. And the atmosphere was festive and extraordinary, at its greatest of the entire year.

For more details:

Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: Lublin volume, Jerusalem 1957

http://yizkor.nypl.org/index.php?id=1511