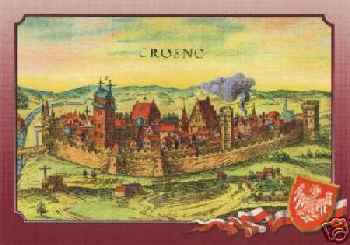

Krosno in southeastern Poland, east of Krakow, was founded in

1324 on lands belonging to the crown. The postcard on the left

(donated by Deb Raff) shows the midieval fortified town of Crosno.

The city's weaving industry played an important role in the

development of Krosno and perhaps contributed to the name

of the city, loom in Polish . The city was also an

important trade center for Hungarian wines. In 1348 it was granted

a municipal charter  based on the Magdenburg laws.

Somewhat later, Krosno was granted the right to hold an annual

fair that became well known. This commercial boost and the

protection of a city wall enabled it to flourish.

based on the Magdenburg laws.

Somewhat later, Krosno was granted the right to hold an annual

fair that became well known. This commercial boost and the

protection of a city wall enabled it to flourish.

Known to the Jewish inhabitants as Kros, Krosno became an important industrial, trade and craft center in the 16th century and had about 250 artisans organized in 10 guilds; the total population exceeded 3000 people. The city attracted many artists and became known as " little Krakow". The various wars, invasions and partitions brought a halt to the growth of the city. It remained dormant until the second half of the19th century.

The first Jews to settle in Krosno were the brothers Nechemia and

Lazar of Regensburg in Germany who received special permits from

the Polish King, Wladyslaw Jagiello in the 15th century. But there

was no continuity of Jewish life in the city. Here and there a Jew

was permitted to reside within the city walls but no trace of

organized Jewish community life. The city population vehemently

opposed Jewish presence.  The guild members led the fight to

keep the Jews out of the city. Krosno finally received from the

crown in 1569 the privilege " de non tolerandis Judaeis " barring

Jews from residing and trading within the city walls. Jewish

traders living in nearby townships of Korczyna, Rymanow or Dukla

were frequently jailed and their wares confiscated for attempting

to enter the city. Still, Jewish merchants from nearby towns

maintained contact with the city and the property census of 1851

indicates that there were three Jewish families in Krosno: Loje

Grusnspan, Mojzesz Grunspan and Schije Dym

The guild members led the fight to

keep the Jews out of the city. Krosno finally received from the

crown in 1569 the privilege " de non tolerandis Judaeis " barring

Jews from residing and trading within the city walls. Jewish

traders living in nearby townships of Korczyna, Rymanow or Dukla

were frequently jailed and their wares confiscated for attempting

to enter the city. Still, Jewish merchants from nearby towns

maintained contact with the city and the property census of 1851

indicates that there were three Jewish families in Krosno: Loje

Grusnspan, Mojzesz Grunspan and Schije Dym

The Austrian annexation of Galicia induced several major social changes that affected Jewish life in the area. The limitations on marriages were lifted, the limitations on the residence of poor Jews were eased, professions were opened to Jews, and land could be purchased by Jews. Finally, the new Constitution of 1867 granted all citizens equality before the law. All these changes encouraged and stimulated Jews to leave their villages and hamlets for the larger cities that offered larger opportunities. Krosno was no exception, fifty families settled in the city between 1859-1890 and other 32 families arrived in the next ten years. To these official statistics we must add the unrecorded arrival of single people who lodged with families and frequently used the family name as their own until things were settled and they obtained jobs or positions. This enabled them to bring their family or to start a family.

The table below shows population of Krosno at various times:

| Year | Population | Catholic | Jew | Orth. Catholic |

| 1870 | 2132 | 2100 | 26 | 620 |

| 1880 | 2461 | 2318 | 113 | 30 |

| 1890 | 2839 | 2454 | 327 | 58 |

| 1900 | 3276 | 2664 | 567 | 45 |

| 1910 | 4353 | 3329 | 961 | 63 |

| 1914 | 5521 | 3893 | 1558 | 70 |

| 1921 | 6287 | 4490 | 1725 | 72 |

The above figures show the rapid growth of the Jewish population which outpaced the overall growth of the city as oil was discovered in the area and money flowed in to develop the industry. The railway, linking Krosno with Jaslo and Europe, followed in 1884. Industries began to develop, especially the weaving and glass making sectors. Krosno was in the midst of an economic boom. Jews kept streaming to the city and even beyond it to the distant lands of Germany and the USA.

On January 1st, 1900, the governor of Galicia granted the Jews of Krosno the right to organize their community or kehillah. The elected leaders then proceeded to organize the various local services including:

creation of a burial society, and

creation of a burial society, and

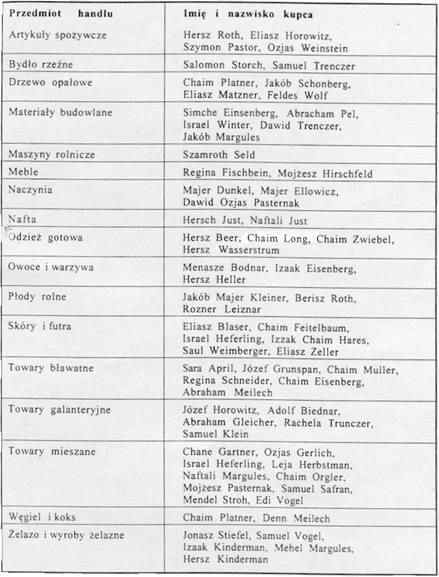

The list begins with groceries, animals for slaughter, wood, building materials, farm tools, furniture, utensils, fuel, ready to wear clothing, fruit and vegetables, agricultural products, skins and furs, draperies, hardware stores, variety stores, coal and coke, metal and metal workshops. The table below shows the List of Merchants (originally in Polish, then translated into English).

The growing Jewish population created the need to open special Jewish stores such as butcher shops, fish stores and bakeries. In 1906 there were already two established baking families in the city, Selig Findling, and Chaim Oling. Fulka Breitowitz, Moses Breitowicz, and Wolf Mahler owned three Jewish slaughterhouses. Sender Fessel, Jacob Grunspan, and Tobiah Nagiel, owned butcher shops. Dawid Mehl led the metal industry that included Chaim Korba, Jakub Pinkas and Jonasz Steifel.The spirit industry was led by Schije Dym and Isaac Hertzig. Tax collections were in the hands of Hersh Wasserstrum and the Dym family. Jewish tailors, barbers, glaziers, shoemakers opened stores or workshops. Ritual slaughters and Hebrew teachers found employment in the city. The Jews dominated and expanded the commercial base of the city. They also developed small industries. Jewish artisans and craftsmen opened and expanded workshops.

| Surname, first | Trade (in English) | Trade (In Polish) |

| April, sara | Fabrics | Towary blawatne |

| Beer, hersz | Ready to wear | Odziez gotowa |

| Biednar, adolf | Clothing accessories | Towary galanteryjne |

| Blaser, eliasz | Leather & furs | Skory i futra |

| Bodnar, menasze | Fruits and vegetables | Owoce i warzywa |

| Dunkel, majer | Kitchen items | Naczynia |

| Eisenberg, chaim | Fabrics | Towary blawatne |

| Eisenberg, izaak | Fruits and vegetables | Owoce i warzywa |

| Eisenberg, simche | Construction items | Materialy budowlane |

| Ellowicz, majer | Kitchen items | Naczynia |

| Feitelbaum, chaim | Leather & furs | Skory i futra |

| Fischbein, regina | Furniture | Meble |

| Gartner, chane | Various goods | Towary mieszane |

| Gerlich, ozjas | Various goods | Towary mieszane |

| Gleicher, abraham | Clothing accessories | Towary galanteryjne |

| Grunspan, jozef | Fabrics | Towary blawatne |

| Hares, izzak chaim | Leather & furs | Skory i futra |

| Heferling, israel | Leather & furs | Skory i futra |

| Heferling, israel | Various goods | Towary mieszane |

| Heller, hersz | Fruits and vegetables | Owoce i warzywa |

| Herbstman, leja | Various goods | Towary mieszane |

| Hirschfeld, mojzesz | Furniture | Meble |

| Horowitz, eliasz | Grocery items | Artykuly spozywcze |

| Horowitz, jozef | Clothing accessories | Towary galanteryjne |

| Imie i Nzwisko kupca | Trade | Przedmiot handlu |

| Just, hersch | Oil | Nafta |

| Just, naftali | Oil | Nafta |

| Kinderman, hersz | Metal & metal items | Zelazo i wyroby zelazne |

| Kinderman, izaak | Metal & metal items | Zelazo i wyroby zelazne |

| Klein, samuel | Clothing accessories | Towary galanteryjne |

| Kleiner, jakob majer | Agricultural items | Plody roine |

| Leiznar, rozner | Agricultural items | Plody roine |

| Lang, chaim | Ready to wear | Odziez gotowa |

| Margules, jacob | Construction items | Materialy budowlane |

| Margules, mehel | Metal & metal items | Zelazo i wyroby zelazne |

| Margules, naftali | Various goods | Towary mieszane |

| Matzner, eliasz | Heating wood | Drzewo opalowe |

| Meilech, abraham | Fabrics | Towary blawatne |

| Meilech, denn | Coal | Wegiel i koks |

| Muller, chaim | Fabrics | Towary blawatne |

| Orgler, chaim | Various goods | Towary mieszane |

| Pasternak, dawid ozjas | Kitchen items | Naczynia |

| Pasternak, mojzesz | Various goods | Towary mieszane |

| Pastor,szymon | Grocery items | Artykuly spozywcze |

| Pel, abracham | Construction items | Materialy budowlane |

| Platner, chaim | Coal | Wegiel i koks |

| Platner, chaim | Heating wood | Drzewo opalowe |

| Roth, berisz | Agricultural items | Plody roine |

| Roth, hersz | Grocery items | Artykuly spozywcze |

| Safran, samule | Various goods | Towary mieszane |

| Schneider, regina | Fabrics | Towary blawatne |

| Schonberg, jakob | Heating wood | Drzewo opalowe |

| Seld, szamroth | Farm machines | Maszyny roinicze |

| Stiefel, jonasz | Metal & metal items | Zelazo i wyroby zelazne |

| Storch, salomon | Cattle | Bydio rzezne |

| Stroh, mendel | Various goods | Towary mieszane |

| Trenczer, dawid | Construction items | Materialy budowlane |

| Trenczer, samuel | Cattle | Bydio rzezne |

| Trunczer, rachela | Clothing accessories | Towary galanteryjne |

| Vogel, edi | Various goods | Towary mieszane |

| Vogel, samuel | Metal & metal items | Zelazo i wyroby zelazne |

| Wasserstrum, herz | Ready to wear | Odziez gotowa |

| Weinberger, saul | Leather & furs | Skory i futra |

| Weinstein,ozjas | Grocery items | Artykuly spozywcze |

| Winter, israel | Construction items | Materialy budowlane |

| Wolf, feldes | Heating wood | Drzewo opalowe |

| Zeller, eliasz | Leather & furs | Skory i futra |

| Zwiebel, chaim | Ready to wear | Odziez gotowa |

During the Austrian period, some Jews served in government offices. These officials were retired with Polish independence. There were only two Jews that worked for the civil service in Krosno namely Dr. Samet who gave Jewish religious instruction in the city school system and Spiegelman who worked in the post office. Jews were by and large absent from the ranks of the police forces, regular army, judicial branch or governmental civil service. They concentrated in the fields of commerce, commercial services, professions and small industry. Jews were not hired as industrial workers in the Krosno plants, especially the glass plant, the linen factory, the Tepege tool and dye plant and the "Wudeta" rubber plant that produced footwear and bicycle tires. Two Jews built the factory namely Wurzel and Daar from Tarnow. Some Jews worked in the offices of the plants but not on the production line.

During WWI, the Russian army occupied the city. The Russian soldiers looted and robbed Jewish stores and apartments. The Jewish population was instantly pauperized. Epidemics broke out and many families fled the city to return with the end of the war. The city economic life was in shambles. The American Joint Organization and the Krosner landsmanshaft in the USA {former Jews of Krosno} helped financially the revitalization of the Jewish community. Slowly the city resumed life and with it the Jewish residents. But the Polish residents of the city resented the Jewish economic presence in the city and organized boycotts aimed at Jewish stores and supported Polish co-operatives that barred Jewish commerce. The campaign intensified with time and reached a high level of confrontation. Only the winds of war ended the campaign of hatred.

Jews were by and large excluded from the social life of the city. They met the general population during the intercourse of the day for purposes of business or professional consultations. There was no socialization after work hours between the Jewish and the Christian population. The Jews organized their own societies to care for their needs. Krosno had a burial society or "Hevrah Kadisha" that tended to the needs of the deceased. Chaim Fruhman and Jacob Palant headed the society. The family usually paid the burial expenses unless they could not afford it, then the community assumed the financial burden. Krosno had a Bikur Cholim society that helped the sick. It also had a society that cared for the poor, "Tomchei Aniim" headed by Kalmen Bogen. He also headed the society for helping poor indigenous Jews that were not residents of the city. This hospice provided sleeping accommodation for one or two nights without charge and was located near Teitelbaum's inn. There were also several small Jewish banks and several mutual fund societies to help the distressed. The Jews usually kept to themselves.

The great preponderance of the Jewish population of Krosno was religious. The religious range extended from the Hassidic or very pious to the moderate or traditional religious Jews. Of course, there were some non-believers, agnostics and assimilated Jews, but they were a small minority. Jewish life revolved around the synagogue. The community built a beautiful synagogue that had three floors. The upper floor was the main synagogue of the community where Rabbi Fuhrer conducted services. The cantor of the main synagogue was Ruben Peretz Kaufman, a brother in law of the famous world-renowned cantor Yossele Rosenblat. The lower floor also served as a synagogue where the Hassidic Rabbi Arale (Aaron) Twerski, a scion of the well-known Hassidic Twerski family, conducted services. Rabbi Moshe Twerski was brought to Krosno by some well to do Hassidic Jews and established his residence in the city. His wife was the sister of the famous Rabbi of Radomsk who actually resided in Sosnowiec. When Rabbi Moshe Twerski died, his son Aaron Twerski inherited his seat in accordance with Hassidic tradition. The lower synagogue attracted the more religious and Hassidic elements in the city. The small yeshiva of Krosno also used this shul for studies.

The second floor also had another synagogue namely the "Yad

Harutzim" shul where merchants and artisans prayed. The third

floor contained the  "mikvehs";

there was a cold and a warm mikvah. The kehilla also provided a

steam room. The sexton of the synagogue and his family also lived

on this floor. Services were also held at the home of Rabbi

Twerski that faced the main city square. The Rabbi shared the

house with the Lang family. The city also had a few small

"shtibelech" or one room service halls, notably the Gerer shtibel

next to Wilner's residence where followers of the Rabbi of Gur

prayed. The community also maintained a religious judge or

"dayan" Akiva Hammerling who was in charge of the rabbinical

court. There were also a few religious slaughterers who charged

the customers for their services. The latter were subsidized for

people who could not afford it. The community also baked matzot

for Passover at the bakery of Krill and provided the needy with

the staples for the holiday. The budget of the community was based

on taxes raised by the kehilla of all Jewish residents in the

city.

"mikvehs";

there was a cold and a warm mikvah. The kehilla also provided a

steam room. The sexton of the synagogue and his family also lived

on this floor. Services were also held at the home of Rabbi

Twerski that faced the main city square. The Rabbi shared the

house with the Lang family. The city also had a few small

"shtibelech" or one room service halls, notably the Gerer shtibel

next to Wilner's residence where followers of the Rabbi of Gur

prayed. The community also maintained a religious judge or

"dayan" Akiva Hammerling who was in charge of the rabbinical

court. There were also a few religious slaughterers who charged

the customers for their services. The latter were subsidized for

people who could not afford it. The community also baked matzot

for Passover at the bakery of Krill and provided the needy with

the staples for the holiday. The budget of the community was based

on taxes raised by the kehilla of all Jewish residents in the

city.

Jewish political life revolved around the community. Who will control the community? Factions and sub factions based on personalities, wealth, political views, religious feelings and social issues fought for control of the community or kehilla. The elections were proportional and very democratic. The elected candidates selected the officers of the community. Usually the officers represented coalition forces within the community.

Some of the leaders of the Krosno Jewish community were:

Bendet Axelrod, Mojszes Weisenfeld, Meshulem Weinberg, Wolf

Hirshfeld, Samuel Stiefel, Leopold Dym and Ozjasz Heller.

Bendet Axelrod was born in Korczyna to the well known towel

industrialist Meshulam Axelrod. Father and son were distinguished

community leaders in their respective cities.  Bendet Axelrod (or Akselrad) pictured at left was born on April

14th 1886 and killed on July 15th 1943 at the Szebnie

concentration camp in Poland. He was the head of the Jewish

community in Krosno for many years and was also active on behalf

of Jewish interests during the existence of the ghetto in Krosno.

These people represented the various political parties in Krosno.

Hirshprung and Fessel headed the Aguda or very religious party.

Dr. Leopold Dym headed the Mizrahi or moderate Zionist religious

party. Josef Horowitz, Samuel Rosshandler, Samuel Stiefel, and

Aron Wallach led the General Zionist party. Hersh Altman and

Itzik Salomon led the Revisionist or right wing party. Of

course, there was also a Hitachdut group that represented several

left wing groups that supported the working movement in Palestine.

All these political parties had youth branches that were very

active in Krosno, for the youth saw no outlet for their hopes

since most avenues of general life were closed to them in Poland.

Bendet Axelrod (or Akselrad) pictured at left was born on April

14th 1886 and killed on July 15th 1943 at the Szebnie

concentration camp in Poland. He was the head of the Jewish

community in Krosno for many years and was also active on behalf

of Jewish interests during the existence of the ghetto in Krosno.

These people represented the various political parties in Krosno.

Hirshprung and Fessel headed the Aguda or very religious party.

Dr. Leopold Dym headed the Mizrahi or moderate Zionist religious

party. Josef Horowitz, Samuel Rosshandler, Samuel Stiefel, and

Aron Wallach led the General Zionist party. Hersh Altman and

Itzik Salomon led the Revisionist or right wing party. Of

course, there was also a Hitachdut group that represented several

left wing groups that supported the working movement in Palestine.

All these political parties had youth branches that were very

active in Krosno, for the youth saw no outlet for their hopes

since most avenues of general life were closed to them in Poland.

The Betar youth movement on the right was headed by Moshe Montag, the Noar Dati was the youth wing of the moderate religious party, Noar Iwri represented the center group. Gordonia and Shomer Hatzair represented the left groups. There was also the Hehalutz movement that organized and trained youngsters to settle in Palestine. As a matter of fact, most of the Zionist youth groups stressed the study of the Hebrew language and stressed the importance of Palestine as a home of the Jews. These youth societies had their own clubs that provided a social meeting ground for the Jewish youngsters.

Jews participated heavily in municipal elections and supported usually moderate city councilmen or they voted for Jewish lists that combined several political parties. There was always Jewish city councilmen in Krosno to defend the Jewish interests in the city. Some of these councilors were frequently re-elected, namely, Eber Englander, Leopold Dym and the Stiefel brothers. The mayor of the city was always Christian. The general elections were usually gerrymandered in such manner as to reduce to the minimum the number of Jewish seats in Parliament. There they were usually kept in isolation and out of reach of influence.

Rabbi Twersky organized a small Yeshiva named "Keter Hatorah" for those students that wanted to continue to study in an organized framework. The head of the Yeshiva was Mr. Seligman. A school for girls was also established in Krosno under the leadership of Mr. Hirschfeld. A school where Hebrew was the official language of instruction was established in Krosno. The school was small but grew in numbers with the years; it was affiliated with the "Tarbut" movement or cultural movement that had a network of schools in Poland. Most Jewish children went to the Polish public elementary schools where their experiences were far from happy.

Very few students continued their studies, since secondary school was very expensive. Some Jewish students opted for trade or commercial classes, but the number of students was very limited due to the expense and the built in system of limitations for Jewish students. Very few students continued higher education that required extensive financial backing. Furthemore, Polish universities limited the number of Jewish students. Some of these went abroad to study. Still the number of Jewish professionals was impressive. Krosno boasted several Jewish medical doctors, lawyers and engineers.

All Jews were ordered to wear a white armband with a blue star. They were forbidden to enter parks or public institutions but they remained in their apartments and kept their business, those that were not looted in the first days of the occupation. Some of the wealthy Jews were forced to leave their apartments in order to make room for the new rulers. The Germans appointed Yehuda Engel head of the "Judenrat". He was a native of Krosno who lived many years in Germany and was kicked out by Hitler. His assistant was Moshe Kleinman. They then selected a council of several members that included Dr. Jakub Baumring, Mosze Weisenfeld, Samuel Rosshandler and Mendel Bialywlos. The council soon created a Jewish police and some special social departments to cope with the many problems, notably, the Jewish refugees that arrived penniless from Lodz and other areas. These people were practically dumped at the Krosno railway station. They were lodged and to a certain extend fed by the council. The council had created a J.S.S. (Jewish Self-Help) committee that was supported financially by the local Judenrat and the main office of the J.S.S. in Krakow. This committee established a free food kitchen for those that could not afford to pay for the food. The JSS also provided food allocations for the needy prior to holidays.

The Krosno "Judenrat" was totally controlled by the Gestapo and carried out all their demands to the letter. Yehuda Engel consulted to a certain extent his council but basically run the show himself. He tried to alleviate the situation where possible but had to provide labor forces for the various needs of the German occupiers. He was also ordered to establish a list of the Jewish population of Krosno in June of 1941. The list has 72 names. We don't know how accurate the registration was or whether everybody was registered. Some of the survivors indicate that the list is pretty accurate although they themselves are not listed. The pauperization of the Jewish community continued at a rapid paste, especially after Germany attacked Russia. Hunger, misery and fear were the daily lot of the Jew in Krosno. Then posters appeared on August 9th, 1942 ordering all Jews to appear the next day at 9 AM at the Targowica square (the old cattle market, next to the railway station). They were all limited to a 10-kilo suitcase. They assembled on August 10,1942. Here, the selection was held, the young and able bodied were spared, the old and sick were taken to the forest near Brzezow and shot. About a thousand people were pushed onto a train that will head in the direction of the death camp of Belzec where they will all perish. All day, the Germans searched the city for hidden Jews and shot them on the spot upon discovery. The same evening, a small ghetto that already existed for several weeks was sealed off from the rest of the city. The new ghetto contained about 300-600 Jews. They remained there until Friday, the week of Hannukah, December 4th, 1942, when they were all shipped to the ghetto of Rzeszow, or Reishe. Some Jews still remained in the area of Krosno where there were several labor camps namely at the Krosno military airport. There a large number of Krosno Jews were employed including Yaakov Breitowicz and Alexander Bialywlos; but the city was essentially clear of Jews. Some Jews were hidden namely Stefan Stiefel and a few Jewish children including Batia Axelrod, the daughter of Bendet Axelrod, and a member of the Nussbaum family

With the liberation of the city of Krosno, some Jewish survivors began to appear amongst them Vitka Kempner. She was a resident of Kalisz in the area of Poznan that reached Wilno during the German occupation of Poland. She joined Abba Kovner’s partisans and fought the Germans until they were defeated by the Russians. Following the war, Kovner directed her to assume the “Bricha” or escape route office in Krosno. The “Bricha” organization was a secret organization dedicated to send all Jews of Eastern Europe to Palestine. The members of the organization were ex-partisans, soldiers of the Jewish brigade and camp survivors. The city of Krosno was located near the Polish-Czechoslovakian (presently Slovakian) border. Surviving Jews reached the city as individuals or groups and were organized into transports. Vitka then took them across the Polish border into Slovakia where they continued their journey to the Rumanian ports on the Black Sea; there ships would take them to the shores of Palestine. Vitka Kempner managed this office for almost one year, from about the middle of 1945 to the middle of 1946. This youngster with some assistants managed to run the office quite successfully during this chaotic period in Poland, where Jews were killed sporadically across the country. As the Polish government improved her control of the country, her borders were closed. The Bricha office in Krosno was closed. Vitka and her assistants disappeared only to reappear later in Palestine. The few surviving Jews of Krosno left the city, and thus ended Jewish history in Krosno.

Bibliography:

William Leibner, Jerusalem, Israel, June 20th 2000; updated July 27th, 2004, updated January 2009.

The Krosno Landsmanshaft was mentioned in the article by Bill Leibner, above. So we know that at least one existed, the Krosno Yedliczer Youn Men's Benevolent Society. At this time we believe that this society is no longer in existence. We were unable to locate the NYC incorporation papers of the Krosnoer Landsmanshaften, but we will continue searching. In these papers the details of incorporation and the founding officers are usually listed. These societies were created for voluntary mutual benefit and aid ...voluntarily aiding the members and family financially in case of necessity or illness ...and assistance from time to time in case of need.

Typically the Landsmenshaften owned a common cemetery plot. The photograph on the left is of the Krosno Yedliczer Young Men's Benevolent Society. We found this one in Beth David Cemetery, just outside of New York City. The graves are all registerred in our JewishGen burial database at https://www.JewishGen.org/databases/cemetery/. If you have any information about the society or a cemetery plot, please contact Jeff Alexander.

In October of 2012 I received the photograph of the Krosno Yedliczer Landsmenshaften gate on the right from Elissa Sampson. The date of the gate is May 30, 1928 and the names of the officers from this landsmanshaften were:

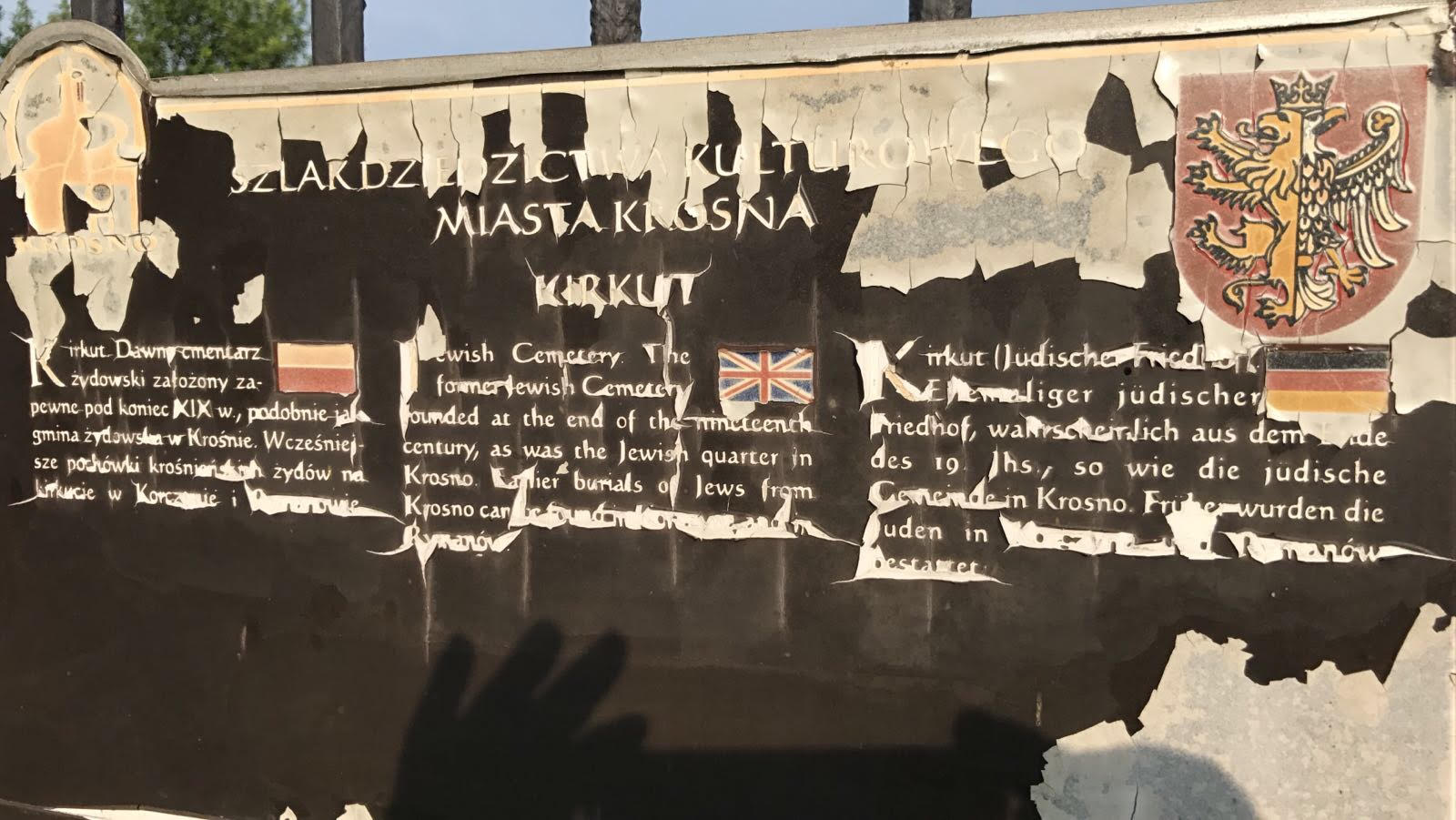

The photographs of the KROSNO cemetery were donated by Ruben Weiser of Buenos Aires . We have tried to initiate a project to decipher the tombstone inscriptions from the many photographs taken by Ruben. If we get this job completed, we will post all the information from the tombstones on this web page.

Up until 2019, Phyllis Kramer (OBM) developed and maintained this KahilaLink. Phyllis did a wonderful job documenting and sharing information about this shtetl. Starting in July 2021 Jeff Alexander is trying to fill Phyllis’ shoes. Please contact Jeff Alexander for anything related to this shtetl

Copyright © (2022) Jeffrey Alexander. All rights reserved.