Where was Kolk?

by Alex Kolker

Where was Kolk?

by Alex Kolker

| For years we have all

heard the story: how a young man coming off the boat

from Russia was asked his name by the immigration

officials, how either he could not understand their

question or they could not understand his answers, how

his declaration "I am a Kolker" meant that he would

never go by his original surname -- "Biskovalia" --

ever again.

But what sort of place was Kolk -- the tiny town where our ancestors had lived for generations? And is there any trace of it left today? GEOGRAPHY: "Kolk" is actually the German name for the shtetl. The Yiddish name is "Kolki." It was located on the banks of the Styr River, in the Volyn Oblast (Province), in the state of the Ukraine, at 51.6 longitude and 21.40 latitude -- seventy kilometers from Lutsk and five hundred kilometers from Kiev. The black arrown on the map below gives its general location.

Our next map is a section of a United States Army Corps of Engineers survey map compiled from air reconnaissance photos in the early 1950s. The map is so detailed that individual buildings are indicated on it, which gives us a better idea of the relative sizes of these towns (although, admittedly, only their relative sizes after the Holocaust).

The map shows that Kolki was a small country town in a rural area. Its location at a crossroads, and the fact that there are several smaller towns gathered around it, probably indicates that Kolki was some sort of trading or cultural center for the Jewish community in the region. In fact, there are some people who believe that Jews for several miles around would have thought of themselves as "Kolkers" -- that the name refers not just to the town itself but the surrounding towns as well.

For those of you who can read the Cyrillic alphabet, you can also find Kolki and Bel'skaya Volya on this modern-day map (Kolki is at the bottom left of this image). One final note: although this doesn't show up clearly on the reproduced images here, Kolki and Bel'skaya Volya are both located in swampland -- in a region known as "the Pripyat Marshes." THE HISTORY OF UKRAINIAN JEWS: The earliest Jewish settlements in the Ukraine date back to the late 12th century, when a large group of Ashkenazi Jews immigrated northeast out of Austria. In the 14th and 15th centuries, many Jews escaping persecution in Germany and Bohemia fled to the Ukraine, strengthening the Jewish population there. By the mid-1700s, there were eighty separate Jewish communities in the region. This community itself was subject to some persecution by the Gentiles -- most notably the Chmielnicki Massacres of 1648-9 -- but for the most part Ukrainian Jews played a prominent role in the economic well-being of Poland (which had taken control of the region in the 1400s) throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Ukrainian Jews managed many of the region's agricultural estates, were employed by the government to collect duties and taxes, and played an important role in export and import trade. In fact, when Russia annexed the Ukraine in the 18th century, the Cossack authorities opposed expelling the Jews because they were such an integral part of the region's economy. As part of the Russian "Pale of Settlement," the Ukraine continued to foster Jewish ownership and economic involvement. In 1817, 30% of the factories in Ukraine were owned by Jews. Jews were particularly active in the distilling of alcoholic beverages, controlling, at their height, ninety percent of that industry. KOLKI: To what extent did the citizens of Kolki take part in this economic boom? It is impossible to tell now, but the region was mostly agricultural, not industrial. Many descendants of Kolki immigrants (including our own family) have passed down stories that their ancestors trained and groomed horses in the "old country," so it is possible that this was the main industry of the shtetl. Beyond this, Kolki's main claim to fame is native son Lamdan, a Jewish author who wrote about life in the region. He portrayed the Jews of the area as poor and decent, and proud of their Jewish heritage. But what sort of town was Kolki? Accounts have trickled down through the various family lines. Most of the homes there in the 19th century were wooden, and the rest were brick. The people were poor, but being poor in Poland at the time was a relative issue. Jews living in Polish cities and suburbs were poor indeed, but Jews in the country had a much easier life, since most of the families had some chickens and a cow for milk. Kolki Jews worked at all professions: tailors, craftsmen, smiths, teachers, builders. By the twentieth century, the city had split into a Ukraine Zone and a Jewish Zone, The two halves did not mix often -- but the fact that that the town's bazaar was always closed during Jewish holidays shows how much influence the Jewish population had over the day-to-day life of the town as a whole. KOLKI TODAY: Kolki, like most of the Ukraine, was ravaged by the Nazi invasions of World War II. Those Jews who were unfortunate enough to still be living in Kolki when the Nazis came were massacred, and their bodies dumped in a mass grave on the west side of town, on a road leading out of the city. This mass grave is now surrounded by a fence, and marked with a commemorative grave stone. The only other remnant of Kolki's Jewish population still standing in the town today is the Jewish cemetery, which was established in the 18th century. It is located in the town itself, in the hospital grounds opposite the town cemetery. The last known Jewish burial there was 1940. The cemetery is owned by the town itself. It not listed and/or protected as a landmark or monument, and so it has been vandalized often in the last few years. There is no fence around this graveyard, and no gravestones remain. In fact, many more recent visitors to the town have been unaware that this cemetery even exists. EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS: Jimmie Kolker of St. Louis -- not a blood relative as far as we can tell, but another Kolker descendent I've met on the Jewish GenFinder site -- offers these personal observations, from a trip to Kolki he took with his father in 1994: "Kolki is still a very wooded area. There is a Kolki State Forest outside of town, and I believe that, besides horse grooming, a major industry at the turn of the century was logging and timber. [Alex's note: perhaps the family had some experience in the lumber industry from back in the old country!] "Anna -- the Polish/Russian librarian who has made it her business to try to preserve the memory of the Jews of Kolki -- described the time under Polish rule between the World Wars as one when Jews were very active in civic life and lived integrated in the community. She recalls her Jewish neighbors the Weinbergs vividly, including the night they were warned to flee and never seen again. She was not very pro-Ukrainian, so there may have been a separate Ukrainian zone of Kolki, but she proudly showed us pictures of her Polish Catholic father on the city council with Jews, Ukrainians, and Russians and recalls them getting along well, so Jews were not altogether isolated or restricted during the 1919-39 Polish period. "The Volyn Oblast was a part of Poland in the years before World War II. One of the advantages of this is that the whole region escaped the Stalinist destruction of many of the old, charming, bourgeois buildings and farms. Given that it's poor, neglected and anti-Semitic, the village of Kolki nonetheless retains an architectural and cultural unity and charm that other places in the ex-Soviet Union lack. "When the Nazis finally came, the Jews

were herded together and killed largely by "roving

death squads" consisting of at least as many

Lithuanian and Ukrainian pro-Nazis as of German

soldiers." Those who were lucky enough to escape

death became refugees, many finally settling in

Israel. Still others became part of the organized

resistance during World War II -- fighting to drive

the Nazis back out of their country, many at the

cost of their lives.

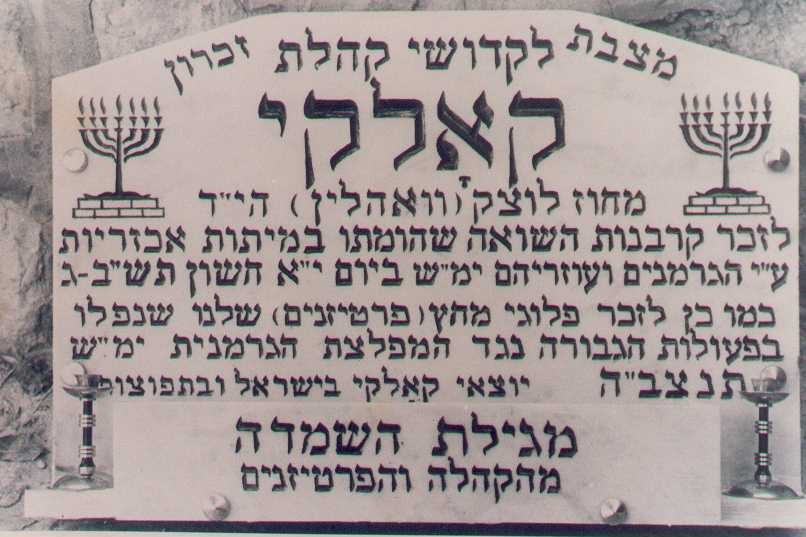

(Below is a better

photo.)  Above is a photograph of a plaque that hangs in the Yad Vashem Memorial in Tel Aviv, commemorating those from Kolki who died in the Holocaust. (The plaque is not cracked -- in the original photo, the left half was in shadow, and I have adjusted the contrast to make it more legible.) It reads:

County of Lutzk (Wohlin), may God avenge their blood. In memory of the

victims of the holocaust who were subjected to cruel Also, in memory of our

partisan units who fell during heroic actions Their souls will be bundled in the bundle of life. This plaque was dedicated by those remaining from the community of Kolki, in Israel and abroad. CONCLUSION: I have often thought of what it must have taken for Monisch to leave home the way he did. He knew that he would never see his parents again. In fact, when he first traveled to America, he left his wife and son behind. He knew no one in America, and he did not speak the language. But he went anyway. I doubt that I myself would have had such courage. And that thought gives me pause. Because it was the descendants of those who didn't leave who were wiped out by the Nazis. In this case, fortune did indeed favor the bold. I am glad, for my sake, that Monisch and Feiga were willing to take this great risk. SOURCES: |

Copyright © Alex Kolker

This site is hosted at no cost by JewishGen, Inc., the Home of Jewish Genealogy. If you have been aided in your research by this site and wish to further our mission of preserving our history for future generations, your JewishGen-erosity is greatly appreciated.