JEWISH COMMUNITY

Contents

Establishment of the Jewish Community

Population

The Jewish Community Through the Partitions and the Duchy of Warsaw

The Jewish Community During Congress Poland

Occupations of Jews in Kotzk

Rabbis of the Community

Other Religious Roles

Kotzk Jews in Independent Poland and the Interwar Period

Members of the Bund

Members of Hashomer Hatzair

The End of the Jewish Community

References

Establishment of the Jewish Community

The first Jews may have appeared in Kock in the first quarter of the 16th

century, when the town became the property of the Firlej family, or, according to other sources, only at the beginning of the 17th

century. One source testifies that in

1639, the Jews received the right of permanent residency in the

city, and enjoyed the rights and duties of the rest of the residents.

The information appearing in some sources that Jews settled in Kock at the end of the 17th

century probably refers to the period when the commune was rebuilt after the destruction during the Khmelnytsky invasion.

Documents from this period indicate that approximately 50–100 Jews lived in the city. The community developed rapidly economically and demographically, so that an independent kehilla was established there before the middle of the century.

In 1648, Khmelnytsky's troops decimated the local Jewish population, but by the beginning of the 18th

century, the Kock kehilla was again flourishing.

Towards the end of the 17th

century, Maria Wielopolska, the owner of the town and niece to Queen Maria Kazimiera (King John III Sobieski’s wife) issued a document in which she obliged local Jews to perform duties to the town the same way Christians did: to provide organized help in case of fires, to keep night watch, and to repair roads, bridges, and dams.

The Jewish Community of Kock appears to have been associated with and possibly subordinate to the Lublin Kehilla in the 18th Century. In 1775, the Commissioner's Court ordered the debts of the Lublin Kehilla to be liquidated. Representatives of the Kehilla during liquidation procedures included Lewek Idzkowicz of Kock, among other senior Kahal members from Lublin and other Jewish communities in the Voivodeship.

Back to Top

Population

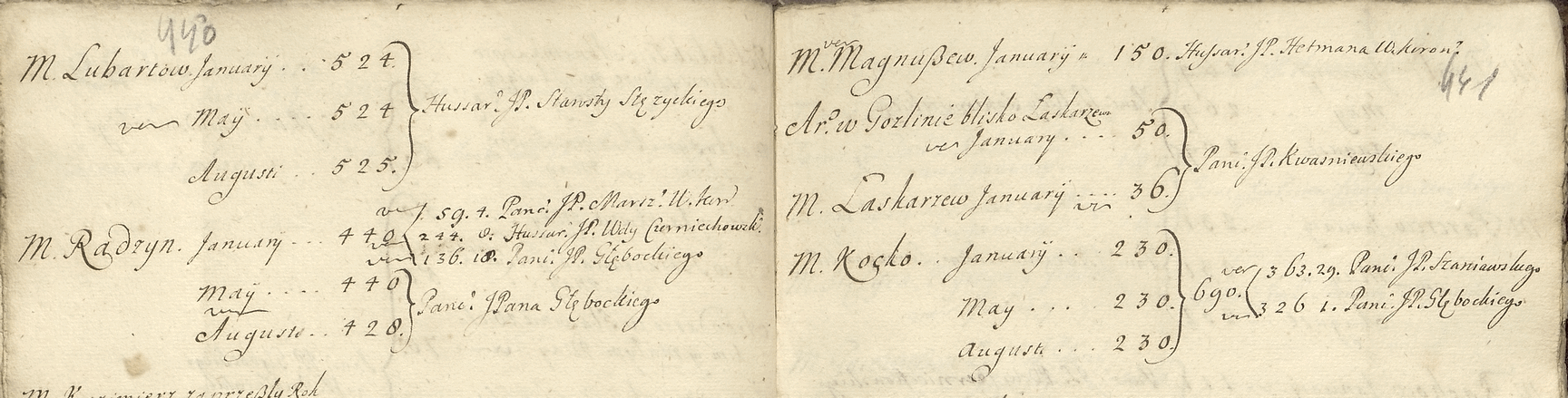

In 1745, the Jewish community in Kock paid 690 PLN in Poll Tax broken into 3 payments during the year. Of the total, 363 Polish Złotys (PLN) and 29 Groschen were collected by J. P. Szaniawski, while 326 PLN and 1 Groschen were collected by J. P. Glębocki. The total collected between Szaniawski and Glębocki = 689 PLN and 30 Groschen.

A portion of the page from the 1745 Poll Tax records showing the tax collected from Kock and several nearby villages. This may mean that there were 690 Jewish people over the age of 8 years living in Kock, though due to varying methods of tax distribution by the Wa'ad , all we can really assume from this information is the population of Jews in Kock might have been larger than the Jewish communities of Zaklikow, Ostrow, Ryczywol, Janowiec, and other communities with smaller amounts, and that the Jewish community of Kock was probably smaller than that of Lipsko, Łukow, Kazimierz, Radzyń, and Lubartów.

In 1764, based on calculations from 1763, the Jewish community in Kock

paid 825 PLN in Poll Tax. Of the total, 724 PLN and 18 Groschen were

collected by the Voivode of Bracław (Anna Jabłonowska?), while 100 PLN

and 12 Groschen were collected by J. P. Ostrowski, listed as a colonel

on another page.

A portion of the page from the 1764 Poll Tax records showing the tax collected from Kock and several nearby villages. Of the Jewish communities listed on this page, Kock seems to be one of the largest and is only overshadowed by Żelechów, Nowe Miasto nad Pilicą, and the Kehilla of Rzeszów, which included multiple towns. Lublin is also listed on this page with a Poll Tax smaller than that of Kock, but this appears to be only part of the tax that was collected from the city.

In 1765, the community numbered 793 people (including Łysobyki) from

which 62 families lived in their own houses. According to the same

sources, half of the Jewish residents engaged in craft (tailors,

milliners, shoemakers, etc.) - and half in small trade.

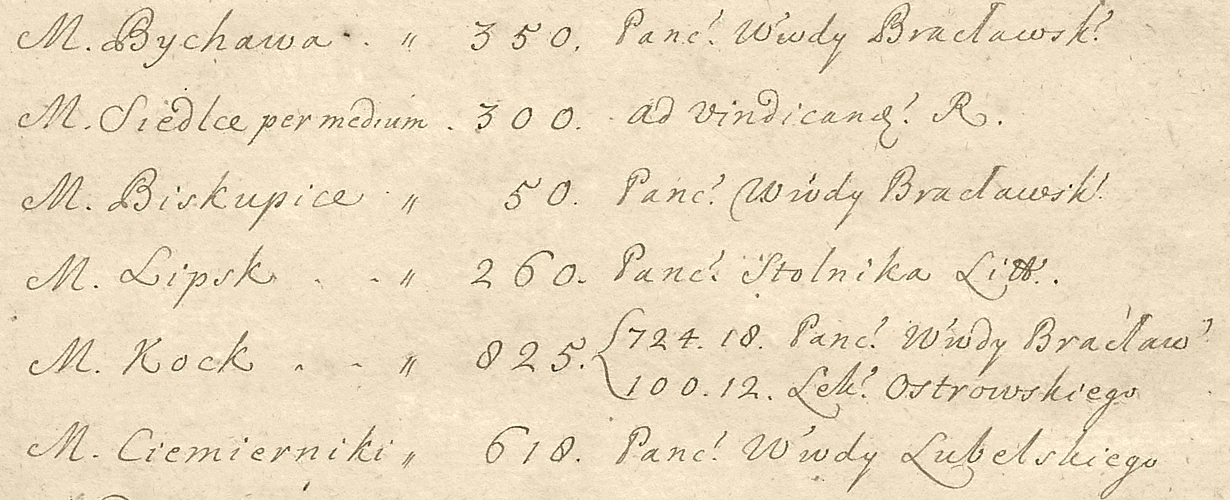

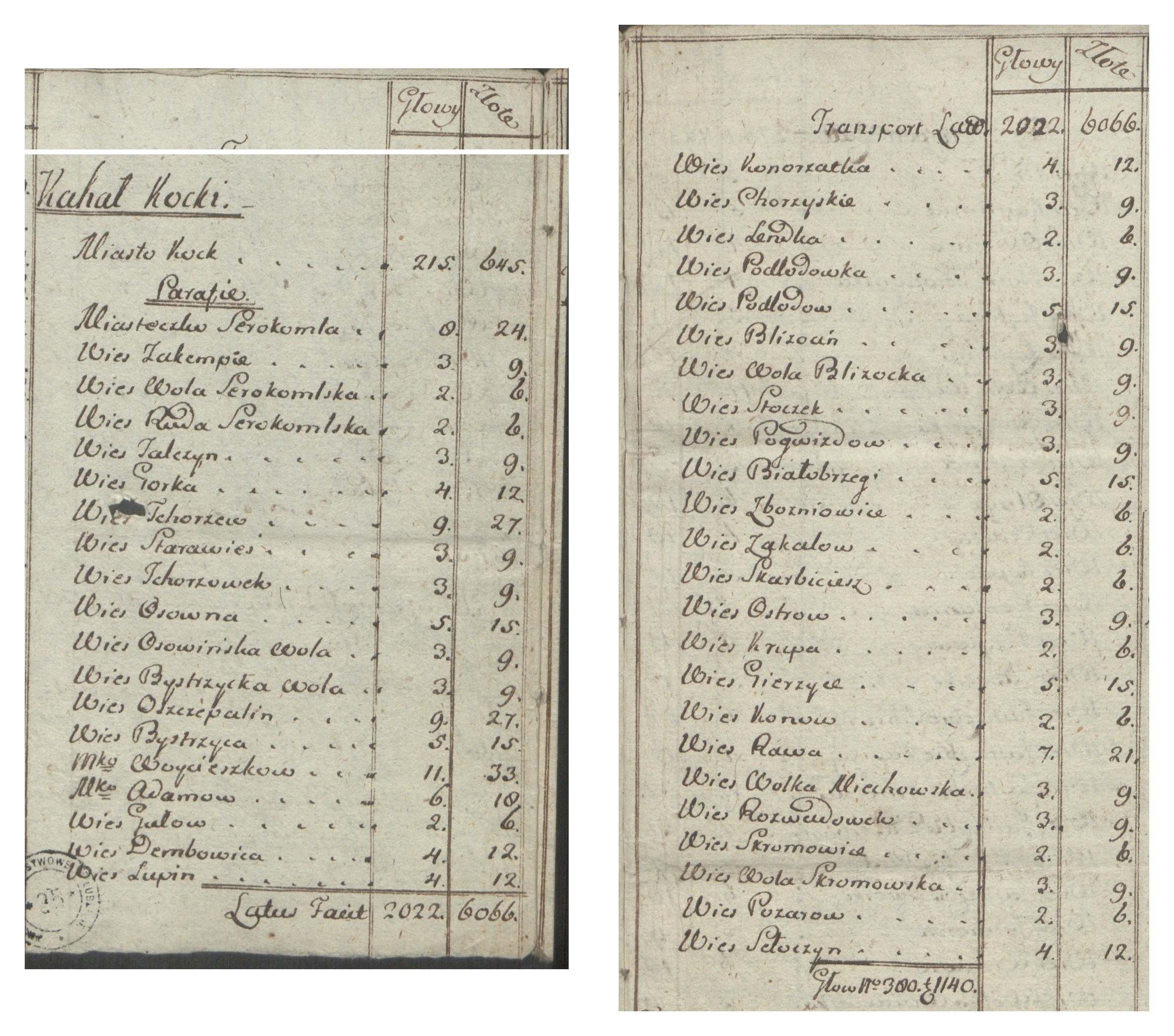

The earliest known statistics for the Jewish population of the kahal and

town of Kock date from the period in which the town was owned by the Duchess Anna Jabłonowska; the second half of the 18th

century. They indicate that the kahal consisted of the town of Kock,

plus three other small towns (Serokomla, Wojciechów, and Adamów), and 40

nearby villages; the number of its members was estimated at about 800,

and they all reported to the Kock kahal.

A portion of a 1778 list of Jewish head taxes for the Lublin Voivodeship, listing the towns and villages within the Kock Kahal. The left column ("głowy") indicates the number of Jewish heads, while the right column ("złote") indicates the tax levied on the community. The list spans two pages - scans 44 and 45 - of a set of relationship files in the Lublin City Records.

Population of the City of Kock over Time

In 1773, Duchess Anna Jabłonowska began to regulate judiciary matters

and kahal elections for Jews living in Kock, and developed rules for

resettling elsewhere and trading in certain types of commodities. During her reign, the Jews of Kock had their own separate judiciary, and the verdicts of the kahal court had to be approved by the Duchess. Cases between Jews and Poles were settled by the municipal court. Therefore the former had their own representative in the court. The Jews, just like the Poles, paid taxes in the form of grain to the public storehouse. Candidates elected to the kahal authorities had to obtain the approval of the court. The Duchess prohibited one person from holding two offices in the kehillah and close relatives from holding office. On the 24th

of June each year, the Jewish community presented to the Duchess its annual accounts.

The Jewish Community paid the following taxes to the state: poll tax, roof tax, czopowe (liquor excise tax) and szelężne (tax on sold liquors). On the other hand, the court treasury received the following payments: posedyłka (capitation tax), lenung, kotłowe, ladowe (paid for stalls) taxes. The sale of a house, shop or stall by a Jew also required the consent of the court. Every Jew leaving the town was obliged to hand over 1/6 of his property to the public coffers, with the possibility of recovering it on his return, within a period of up to three years.

The town was also famous during this period for the frequent large-scale fairs held by Duchess Jabłonowska, which made it an attractive place for Jewish artisans and craftsmen, both for trade and permanent residency.

Back to Top

The Jewish Community Through the Partitions and the Duchy of Warsaw

During the Partitions of Poland, Kock became part of West Galicia,

controlled by the Habsburg Empire, from around 1795 to 1809. In 1809,

thanks to Berek Joselewicz and his infantry, Kock was annexed to the

Duchy of Warsaw and subsequently became part of the Radzyń powiat in the

Siedlce governate. After 1815, Kock was part of Congress Poland,

essentially a puppet state of the Russian monarchy.

Jews living in the Duchy of Warsaw were required to report civil

registry events (births, marriages, deaths, and marriage banns) to the

local Catholic parish as early as 1808-1810. The earliest civil records known for Kock date to 1817, after the dissolution of the Duchy of Warsaw. It is likely that earlier records existed, but they may have been lost or destroyed.

There was a large military presence in Kock throughout the Partition

period and into the Congress Poland years. Beginning around 1780, the

Polish Army managed a Salt Warehouse in the market square, from which

many Jews purchased salt for trade, brewing, and other necessary

functions; the military also acquired the brewery in Kock in 1817. In

1816, the home of Kiwa Goldfinger

of Kock (185 Radzyńska Street) was

purchased by the military for 3,200 PLN and transformed into a military

hospital.

Back to Top

The Jewish Community During Congress Poland

In Kock, the use of surnames began to replace patronyms around 1821,

although some Jews were using surnames prior to 1821 in Kock vital

records. Beginning in 1826, civil records were still

required to be kept by Jews, but were allowed to be maintained by the

Jewish community themselves.

In the earliest available civil records, there are only a few that pertain

to Jewish civil events, much less than the number of Catholic records.

Still, through these records we are able to get a sense of how the

community lived. It is evident that the Jewish community of Kock was

important to surrounding Jewish communities; many records pertain to

Jewish visitors to Kock who lived in Czemierniki, Firlej, Lubartów, Łuków,

Łysobyki (now called Jeziorzany), Serokomla, Serock, Stoczek (both Stoczek Łukowski and a village next to Gmina Kock called Stoczek Kocki), Radzyń Podlaski, Biała

Podlaska, Węgrów, Sławatycze, and Zamość. Many of the early vital records also indicate that Jews primarily lived on the following streets in Kock: along the market square (Rynek), ul. Browarna, ul. Warszawska, ul. Radzyńska, ul. Wesoła, ul. Łysobyki, ul. Białobrzegi, and ul. Solna.

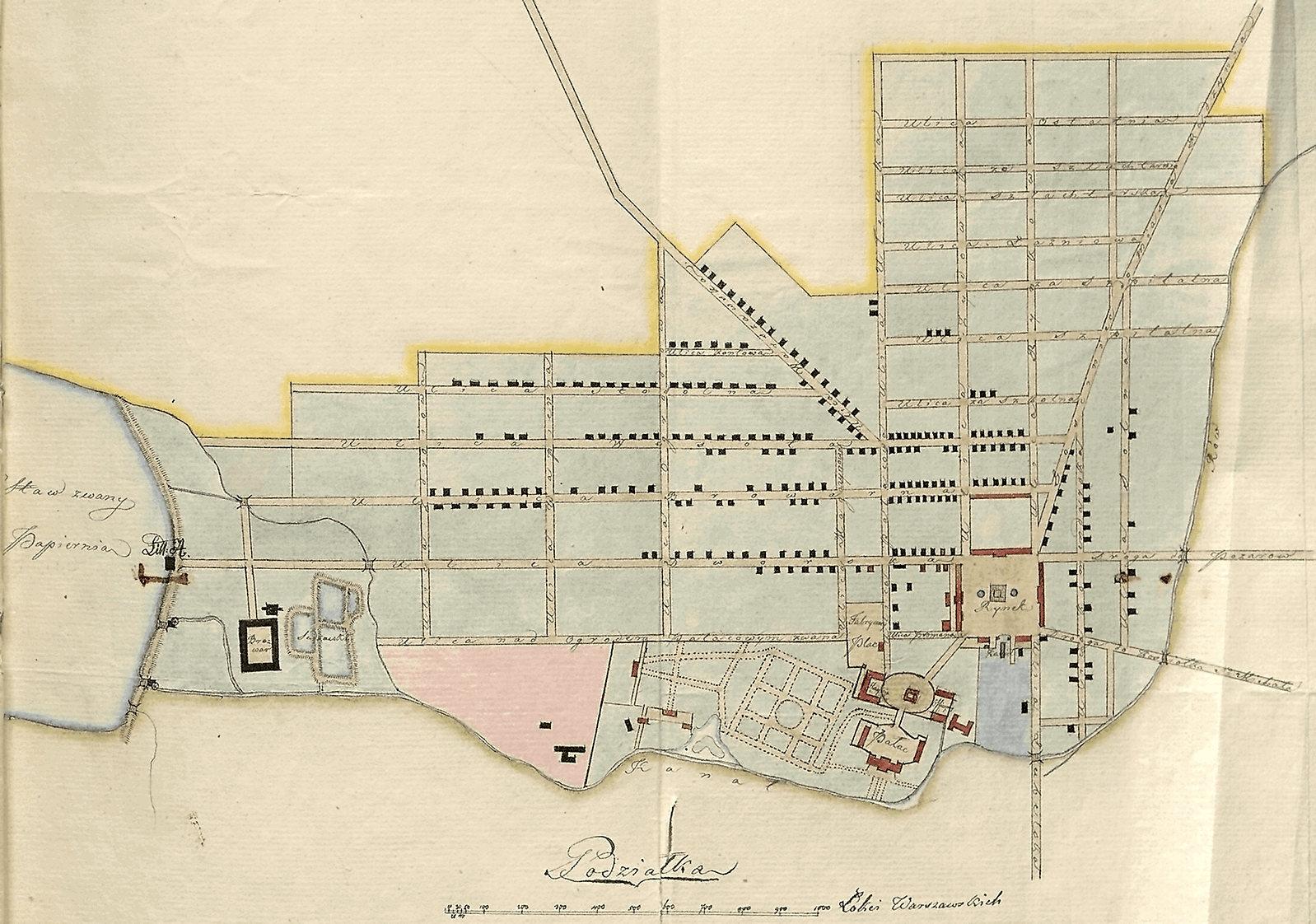

A map of the City of Kock created around 1819-1826. The pond on the left is named Papiernia, which means "paper mill" in Polish. A brewery and saltworks are depicted just to the east of the pond, both of which appear to be relatively far away from the most developed part of the city.

The Rynek (Market Square) is shown near the southeast side of the city, which was located near the palace. The road leading north from the northwest corner of the square was named Ulica Zydowska (Jewish Street) on this map; as the road continues north, it intersects with Ulica Browarna, Ulica Wesoła, Ulica za Szkolna, two roads named Ulica Szpitalna (Hospital Street), Ulica Łaźniowa (Street to the Bathhouses), two streets named Ulica Szlachtarzka , and Ulica Ostatnia (literally: the final street).

Development and growth in the town was slow in the early 1800's. The reason for this was likely the town's distance from the railroad and more populated areas of Poland. Much of the trade between Kock and surrounding villages was conducted by carriage along long-ago-established routes.

During the Polish–Russian War of 1830–31, the uprising spread to Kock. The Kotzker Rebbe was supportive of the uprising and encouraged his followers to join the cause. A report

by the military from 1831 mentions, in relation to impending encroachment of Russian forces:

Unfortunately, another thing that spread to Kock around this time was cholera

, which had spread across many Polish towns. Vital records for the town from the early 1830's show entire families succumbing to disease within the span of a few days to months. In many cases, the cause of death is not reported in the record, which may be due to the absence of qualified personnel to diagnose such a condition (many places were still operating under the Miasma

theory at this time).

Despite these setbacks to population growth, the Jewish community in Kock continued to flourish with the help of their Kotzker Rebbe. The Rynek served as a vibrant center for the economic and social life of the town. At all hours of the day, there were "circles" of Jews, who huddled together in groups and discussed political matters for pleasure. On the "market days," where the surrounding farmers bring their agricultural produce here for sale, Jews from all over would travel to Kock with carts full of wares.

Back to Top

Occupations of Jews in Kotzk

Many of Kock's Jews in the early 1800's were traders, stall-keepers, and merchants. Craftsmen, particularly tailors, were also prevalent in the Jewish community. The community likely traded between the surrounding communities, as

well as other towns owned by the Jabłonowski and Sapieha families. Trade routes had long been established between the nearby town of Lubartów and Gdansk, primarily for the transport of grain.

According to an economic survey of Kock around 1820, there were: 3 tanneries, 7 pottery workshops, 3 smithies, 10 tailors, 19 milliners, 2 leather workers, 3 carpenters, 3 locksmiths, 14 shoemakers, 14 weavers, 2 engravers and one watchmaker. The religion(s) of the owners of these businesses are not specified, but it is likely that most or all are Jewish, as most Christian residents were farmers during this time period. Municipal funds reported in the early 1820's indicate that there were three primary customs duties imposed on predominantly Jewish residents:

Number of Jews in Kock who Paid Customs Duty

In the early 1800's, one of the Synagogue sextons, Szloma Wartownik

, was also a night guard for the community. Around 1839, Marek Berlinski

, the first known Jewish doctor of Kock, moved there with his wife Ernestyna. While they do show up in synagogue vital records, they later became Neophytes

. It seems that his work was impressive enough for his dissertation

to have survived to today!

The economic activity of the Jewish community in Kock was noted in the 18th

and 19th

centuries. Jews then took leading positions in trade and crafts. They dealt with shoemaking, tailoring, pottery, hat making and carpet making.

In the 19th

century, economic and demographic development was undoubtedly related to the increasing importance of Kock as an important Hasidic center. The craftsmen of Jewish origin mentioned in the sources include:

- Coopers (Bednarz):

- Henry Weisman

- Tailors (Krawiec):

- Abram Gedowicz

- Icek Haskiel

- Mordka Jekowicz

- Icek Mortkowicz

- Szymcha Moszkowicz

- Icek Rozumny

- Cloth Dyers (Farbiarza Sukienniczego):

- Jankiel Farberman

- Brass Makers (Mosiężnika):

- Jósef Cygler

- Brewers (Piwowar):

- Johan Ryfer

- Butchers (Rzeźnika):

- Wolw Fraiman

- Turners (Tokarz):

- Abram Bursztynek

- Fajwel Bursztynek

- Traders (Handlarz):

- Moszek Abramowicz

- Fajwel Dawidowicz

- Icek Herszkowicz

- Berek Lejbowicz

- Merchants (Kupiec):

- Dawid Bromberg

- Szloma Zelmonowicz

- Stall Keepers (Kramarz):

- Szmul Kiwowicz

- Erszek Moszkowicz

- Fetka Moszkowicz

The Jews also rented a storage yard on the Wieprz River, which was used to float wood to Warsaw and Gdańsk. In 1855, the tenant of the square was Moszek Michelsohn.

On June 10, 1910, the Jewish Loan and Savings Society was established in Kock. It was an economic association, probably operating as a bank for low-interest mutual loans.

Jews also owned most of the over 100 shops existing in Kock, including many small craft workshops (including some operating illegally) and enterprises trading in grain and wood. There were Jewish cooperatives operating in the city (Jewish Craft Cooperative, Association of Workers' Cooperative "Jedność", Association of Jewish Merchants) competing for influence with Christian organizations, Jewish trade unions (including: Union of Leather and Related Industry Workers, Trade Union of Clothing Industry Workers) and craft guilds (the Guild of Shoemakers, the Guild of Bootmakers, the Guild of Saddlers, the Guild of Tailors, Furriers and Hat Makers), as well as credit unions supporting the development of economic activity by granting low-interest loans (including the Credit Cooperative, the Cooperative Merchant Bank, the Jewish Loan Society).

Back to Top

Rabbis of the Community

The first recorded rabbi of Kock was a son of the Rabbi Mosze ben Isaak Jehuda Lima

, who reportedly became the Rabbi of Kock's Jewish community in 1670. After his death around 1707, Rabbi David became the community's rabbi. The life and actions of Rabbi David are lost to history; according to the Yizkor Book, the only information known about him was that he was the son of Rabbi Natan Neta of Mezritish, who was the son of Rabbi Nachum from Slutsk, who was a great scholar and the son of the Rabbi Meir Wahl

, who's father, Saul Wahl Katzenellenbogen

, was "king for a day" in 1587!

We do not know how long Rabbi David was the rabbi of Kock; his successor, Rabbi Mordechai HaLevi, died circa 1751. The last rabbi mentioned in the Yizkor Book as serving prior to the 1800's is Rabbi Mattiyahu of Kosov, whom is suggested to have been influenced by Hasidism.

The rabbi of the community in the early 1800's was Szloma Friedman

, son of Zelman, who, according to one source, became rabbi of Kock around 1798. He died at the beginning of 1826; it is unclear if there was another rabbi serving in his place

prior to Menachem Mendel Morgensztern's

move to Kock circa 1828.

Kock was also the home of several rabbis of other communities. Most of the rabbis we know of were influenced by Kotzk Hasidism (and are discussed on the page about Menachem Mendel Morgensztern), but at least one other rabbi, Icek Mayzels

(c. 1753-1833), Rabbi of Nowy Korczyn

until his death, had become the rabbi of his community prior to Morgensztern's arrival in Kock.

Back to Top

Other Religious Roles

It is clear from the community's vital records that there was a strong system of religion in place, with two families that adopted the surnames Rechtman

and Wartownik

consistently serving as szkolniks

(sexton, shammes, beadle) in the community.

Throughout the earlier vital records maintained by the Jewish community,

birth and death records typically included a close relative of the record

subject and one or two of the szkolniks

as a witness; marriage records

included a duchowny

(cleric), the Rabbi or Assistant Rabbi

, and generally up to four

witnesses, one or more of whom may have been one of the community's

szkolniks

.

Employees of the Jewish Community in Kock

Back to Top

Kotzk Jews in Independent Poland and the Interwar Period

In September 1919, the Association of Jewish Merchants was established in Kock. 104 members signed up. Around this time, a branch of the Provincial Association of Small Merchants in Lublin operated in Kock, which had about 20 members. In 1924, a branch of the Association of Craftsmen of the Republic of Poland was established in Kock. In 1932, its local management board included:

- Jankiel Cubek (president)

- M. Goldfarb (secretary)

- Nojech Cubek (treasurer)

In 1924, Jews owned all Kock bakeries, butcheries, oil mills and dyeworks. In turn, out of 10 butcher shops, only one was Jewish-owned.

In the interwar period, numerous political parties and organizations operated in Kock, including: the Zionist association "Bnei Zion", which has existed since 1919, the orthodox Agudas Israel party, the Zionist-orthodox Mizrachi party, and the Histadrut Zionist Labor Party. Although there was no separate Bund unit in Kock, it had significant influence in the socio-cultural organizations operating in the city, including the "Kultur Liga" organization and the local branch of the Jewish Craftsmen Headquarters.

The Bund movement in Kock, taken from the Yizkor Book.

- Bundists Named in the Yizkor Book

- Yaakov Leizer Kleinman

- Hatzek L Szeczinarz

- Nachami Reznikovitz

- Shmuel L Kleinman

In the years 1929–1934, there was a cell of the Zionist Organization in Kock, running a library and a reading room. There were also youth groups operating in the city, including Hashomer Hatzair, founded in 1929, and the revisionist-Zionist Brit Trumpeldor.

From 1921, illegal cells of the Polish Communist Party operated in the city, whose program was supported by many Jewish residents of the city, including a significant number of members of trade unions operating in the city. Representatives of Jewish organizations took an active part in the political life of the city - in 1919, the City Council included eleven Jewish councilors:

- Gerszon Bronsztejn

- Abram Czarny

- Szoel Handelsman

- Jankiel Herc

- Icek Krajcman

- Lejzor Siemiatycki

- Moses Wajnberg

- Majer Warum

- Abram Zakalik

- Chaim Szyja Zalcman

- Jojna Zygielmann

The Kock branch of Hashomer Hatzair was created by members of a scouting group that had been established around 1925. Initially founded on December 26, 1929, the Hashomer Hatzair movement in Kock had 67 members by 1933.

- Founders (circa 1925)

- Basha Kot

- Yitzchak Zigelman

- Chaim Shlimak

- David Rosenbloom

- Yaakov Blitman

- Yaakov Moncharz

- Moshe Blitman

- Yoshua Shulstein

- Moshe Friedman

- Members in 1929 and Later Years

- Zvi Medens

- Meir Tzovik

- Hana Moncharz

- Nachum Ehrlich

- Groni Gazivatz

- Esther Blumenfeld

- Menoch Kraitzman

- Matthiya Grossmann

- Yocheved Gazivatz

- Hana Blitman

- Yhiel Rozenblat

- Moshe Samaliar

A photo of members of Hashomer Hatzair at a training camp, circa 1933, taken from the Yizkor Book.

In 1921, a branch of "Agudat Israel" was founded in Kock by the Gerrer Rebbe Berish Kor, which was joined by Leibel Grossman, Mendel Goldstein, Leibel Goldstein, Yosef Mier Erlich, and others primarily of Gerrer Hasid background. The group met opposition from older Hasidim and Ultra Orthodox followers, though opposition waned after Rabbi Meir Shapiro became president of the Polish branch of Agudat Israel. The group became one of the most popular political organizations among Kotzk Jews, with about 120 members at its height. The organization also opened a Yeshiva and a branch of Bais Yaakov in town.

Jewish children in Kock also attended the local public schools with non-Jewish children. In the 1930's there were even some Jewish teachers working in local secular schools, such as Jachwet Rychtenberg.

A photo of Jachwet Rychtenberg with her students. Taken at an unknown date, but likely in the 1920's-1930's. Copyright © "Grodzka Gate - NN Theatre" (Ośrodek "Brama Grodzka - Teatr NN").

Back to Top

The End of the Jewish Community

The Kotzk Jewish community came to an end with the onset of the Holocaust. The last rabbi of the community, Abram Josef Morgensztern, was killed along with his family during a Nazi air raid on the town that occurred on September 9, 1939.

After the surrender of General Fransiczek Kleeberg to the Nazis on October 6, 1939 in front of the Jabłonowski Palace in Kock, the town came under the control of Nazi forces until its liberation on July 21, 1944. Many of the Jewish residents of Kock were deported to labor or extermination camps by the middle of 1942; most of the Jews remaining in Kock after mid-1942 had been transported there from elsewhere.

Less than 30 Jewish residents of Kock are known to have survived the Holocaust. Of these, even fewer survivors tried to return home to Kock. Returning survivors were often met by new occupants of their home, who were often hostile towards them. One of Kock's survivors, Chaia Liss née Rybarczuk, was killed in July 1944 while trying to retrieve possessions she had hidden with a neighbor.

Back to Top

REFERENCES

- "Sefer Kotsk". (1961). [Online, partial English translation], or [Online, OCR full version in Yiddish and Hebrew].

- Kock Guidebook - Shtetl Routes - NN Theatre, Ośrodek „Brama Grodzka – Teatr NN”. [Online, in English] .

- Sulimierski, F. et al., "Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland (Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów słowiańskich)". Vol. IV (1883), pp. 233-234. [Online, in Polish] .

- Virtual Shtetl (Wirtualny Sztetl) page for Kock. [Online, in Polish and English] . Most of the pages are only available in Polish.

- Translated from Polish to English, from the Delet program of Poland's Ministry of Culture and National Heritage: "Pogłówne [Poll Tax]: in the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the most important tax paid by Jews to the treasury, intended for military needs. At the end of the Middle Ages (1466), Jews paid on an equal footing with townspeople. It was not until 1549 (or, according to some researchers, in 1563) that a special "Jewish poll tax" was introduced in the amount of 1 zloty per head, which was applicable to everyone, except for the poorest. In 1580, it was fixed at a lump sum, and its division into individual Jewish lands and communities was decided by the Sejm of Polish Jews and land assemblies [also known as the Va'ad or Waad]. From 1662, in the Crown, all Jews over eight years of age were to pay, and in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania - from 1678 - Jews over ten years of age; however, the old lump-sum rules were soon reverted. In 1764, the Sejm passed a general census of "Jewish heads" in the amount of PLN 2 per head (increased to PLN 3 in 1775), with the exception of children under one year of age . In the Austrian partition, Jews paid tax until 1848, in the Russian partition - until 1862. Although many Jews evaded paying this tax, for the 16th - 18th centuries, the tax registers are the basis for demographic estimates of the Jewish population." - Authored by Pawel Fijałkowski

- Majewski, Jan Stanisław. "Historja Miasta Kocka" (1928). Available through the Municipal Public Library in Radom (Miejska Biblioteka Publiczna w Radomiu): [Online, in Polish].

- Różycki, Samuel. "Zdanie sprawy narodowi z czynnośći w roku 1831 (Report to the nation on the activities [of the Army of the Kingdom of Poland] in 1831)". p. 3. Available through Polona/Academia: [Online, in Polish].