Kimberley, South Africa

Jabotinsky’s Visit to Kimberley in 1938

Compiled by Geraldine Auerbach MBE

London, March 2020

South African, and Kimberley Jewry were fervent Zionists. Towards the end of the 30s, it became more imperative to have a Jewish homeland as news of the treatment of Jews in Europe spread.

Jabotinsky was a stirring orator and inspired writer who had many disciples in the Jewish world, including later Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin. He was also the founder of the Jewish Legion, which fought alongside the British during World War I. In 1935, after the Zionist Executive rejected his political program and refused to clearly define that “the aim of Zionism was the establishment of a Jewish State”, (not just a homeland), Jabotinsky decided to resign from the Zionist Movement. He founded the New Zionist Organization (N.Z.O) to conduct independent political activity for free immigration and the establishment of a Jewish state. Jabotinsky and his team realised that South Africa was a most significant field for raising the funds they so badly needed. So, although he had visited in the early 30s, he made a return visit in 1938.

He was clearly a contentious figure by this time as permission had to be sought for his visit. In May 1938 it weas reported that ‘The South African government will not prevent the temporary entry of Vladimir Jabotinsky, head of the New Zionist organization, the Minister of Interior said in Parliament today in reply to a question. The government does not consider his projected visit to south Africa harmful, the minister said.’

Natalie Kroll (later to be the daughter-in-law of Kollen Sussman and wife of Cecil Sussman) was ten in 1938. She remembers: We were all ardent Zionists led by Dov Senderowitz. We had weekly meetings in the Shul hall. We were ready to fight and to plough. We had dreams of having our own state. (And we were later privileged to see the miracle of our dreams come true).

Page 1 of 14

Jabotinsky’s visit to Kimberley in 1938

But not everyone in Kimberley saw eye to eye. Most of Kimberley Jewry were ‘Old’ Zionists. Natalie remembers the fervent debates between Harry Stoller the ‘Old’ Zionist on the one hand and Dan Jacobson’s dad Hyman (creamery) Jacobson on the other. Daphne Toube, though also a small girl at the time remembers great political rivalry between Harry Stoller and Laz Barnett. This little group of Hyman Jacobson, Lionel Jawno, Laz Barnett and Kollen Sussman were at odds with the rest of the community, all passionate believers in the ideals of Jabotinsky and the New Zionists.

The most momentous occasion in the history of Kimberley Jewry

Milton Jawno writes, “During the late 1930s, my father Lionel Jawno and his brother-in-law Laz Barnett – received in Kimberley the great Jewish leader and modern-day prophet Zeev Jabotinsky. Laz Barnett was a veteran of the great war who had survived the battle of the Somme. Jabotinsky's visit to Kimberley in 1938 was the most momentous occasion in the history of Kimberley Jewry. This great prophet and leader, my father told me, warned the community of the impending hell that was about to decimate our people. Certainly, meeting Jabotinsky was one of the highlights of my father's life”.

Milton says however, ‘This visit was not well received by the then leaders of the Kimberley Jewish community who, to put it mildly, were not supporters of Jabotinsky and shunned my father for his passionate views’.

Dan Jacobson recollects (as a boy of 8) meeting Jabotinsky in 1938 when he visited Kimberley – as referred to by Milton above. His father, Hyman Jacobson, as a passionate ‘New Zionist’ or ‘Revisionist’ was responsible for organising Jabotinsky’s visit. And organising this visit was a huge responsibility because, as Milton says, there was no support from the community who instead favoured the more gentle labour Zionism of Chaim Weitzman. Dan says that Jacobson and the other three or four ‘New Zionists’ who had given him some help, were shunned by the ‘Old Zionists’ and that his father, when his views were known, was ostracised, had to give up the communal positions he had previously held, and certain leading communal figures would not greet him when he passed them in the street.

Dan Jacobson’s description of the visit

This is how Dan Jacobson remembers the visit (writing in Commentary in May 1961)

Almost twenty-five years ago, I met Vladimir Jabotinsky, when in 1938 he visited our home in Kimberley, during a South African tour. I was then a boy of about eight years old. Much of it I can remember vividly, for it was my first meeting with anyone whom I knew to be without question a great man. My father had told me many times how great a man Jabotinsky was.

Page 2 of 14

Jabotinsky’s visit to Kimberley in 1938

The program—as I remember it—for Jabotinsky’s stay in Kimberley was that he was to arrive on the morning plane from Johannesburg, that he would be met by a small reception committee at the airport, and then come to our house for lunch. In the evening he was to address a public meeting in the Town Hall; he was to leave the next day for Cape Town.

In this historic picture in the possession of Laz Barnett’s daughter Ruth, of the reception committee at Kimberley airport in 1938 are:

Left to right Mr Kollen Sussman, Mr Hyman Jacobson (Dan’s father and who had arranged the visit to Kimberley) Mrs Flo Jawno?, unidentified man - was he the Rabbi or the Mayor?, Mrs Jacobson, Vladimir Jabotinsky, Laz Barnet, Freda Barnett

In front are the children Dan Jacobson, and the three Barnett girls, Ruth, Mavis and baby Jessica.

Dan Continued: “The great man had lunch in the spruced up and shining Jacobson house. The non-Jewish mayor at the time accepted Jacobson’s invitation to meet the famous visitor at the airport and Jabotinsky addressed a full house at the City Hall, in a meeting that Jacobson had organised and publicised in the local paper and by distributing leaflets”

After that, instead of going straight to Cape Town, Jabotinsky asked to rest for a while and reflect and chose to go and stay and rest – not in Kimberley itself – but at a small hotel which

Page 3 of 14

Jabotinsky’s visit to Kimberley in 1938

was owned by the Millin family, a distinguished Jewish family whose daughter was the world-famous writer, Sarah Gertrude Millin.in Barkley West, 20 miles out of Kimberley on the Vaal River. (Was he invited to reflect there by the family I wonder?)

Milton said: “My father Lionel Jawno and his brother-in-law Laz Barnet went to Barkley West every day for a week to take a copy of the newspaper and to see that Jabotinsky was well and cared for. This was in an age when there were no proper roads, only numerous farm gates and tracks.” Milton further recalls that in 1956, “Menachem Begin, who was to become a future prime minister and leader of Israel, had dinner with my father and mother Lily at our home. This was because of my father's friendship with Rosh Betar, Jabotinky many years before. My father remained a disciple of Jabotinsky all his life”.

Dan Jacobson’s story continues: “Kimberley is a small town, and no doubt Jabotinsky did not attach any special importance to his stay there; indeed, for the children in our family the awareness of our own unimportance helped to intensify our gratification at his visit. Nothing ever happened in Kimberley, we knew; yet it was to Kimberley that Jabotinsky was coming! And not merely to Kimberley, but to our own workaday commonplace house, which in its very familiarity was the obvious antithesis of anything which might have the name of greatness.

Page 4 of 14

Jabotinsky’s visit to Kimberley in 1938

“What kings, if any, Jabotinsky had talked to, I do not know: perhaps I will learn from the second volume of Mr. Schechtman’s biography. At the time I did not bother to ask. It was enough for me to know that a man who had talked to kings was to talk to me and my brothers, and to my parents, and even perhaps to Martha. Our house shone for the visit; I wished that dusty, drab Kimberley would do the same. But I knew it never would. The burden of meeting the luminary with light was all our own.

“In fact, the burden of greeting Jabotinsky was all my father’s. So far as the New Zionist Organization—as Jabotinsky’s movement was known—had a branch in Kimberley, it was my father. There were a few other “New Zionists” or “Revisionists” in the town, but their adherence to the movement was lukewarm, whereas my father’s was passionate. [Ed: it seems the adherence of the others was passionate too.]

“I suppose the differences between the “New” and the “Old” Zionists are pretty much forgotten by now, even among Zionists; but twenty-odd years ago these differences were, in our house at least, matters of passion, of my father’s passion. The Old Zionists, we were brought up to believe, were pitiable, narrow, cowardly; the New Zionists alone had courage and vision and understanding. The New Zionists boldly demanded not the vagueness of a “Jewish National Home” in Palestine, but nothing less than a Jewish State in an undivided country. They insisted that if the British mandatory power would not accede to this demand, then Britain had to be fought, physically if necessary, inside and outside Palestine. And if the Arabs rose in opposition to the Jews, then it was the duty of the Jews to abandon their defensive policy of havlagah, and lay claim to the country by the strength of their arms—not by the piety of their methods of settlement. The New Zionists campaigned too for a mass exodus of the Jewish communities in Europe, whom they declared to be threatened by imminent death. And of all this, and for all this, Jabotinsky was the instigator and spokesman.

“I shall return later to these aims and claims, and will try to describe a tiny fragment of what they helped to lead to, twenty years later, with a world war, a European holocaust, a campaign of terrorism, and two brief Palestinian wars between. At the moment I merely want to say that as a result of being a follower of Jabotinsky, and holding the views described above, my father had suffered something like a minor boycott in the small Jewish community of Kimberley. He had lost those communal positions he had held before he had announced his views; he had of course resigned from the local Zionist society; and there were certain leading figures in the community who would not greet him when they passed him in the street. Out of all this my father undeniably wrung a certain satisfaction; and it is just for this reason that I cannot help wondering what would have happened to his admiration for Jabotinsky if he had known him for longer.

Page 5 of 14

Jabotinsky’s visit to Kimberley in 1938

“The whole family went out to the airport as part of the reception committee. Apart from ourselves, there were three or four fellow Revisionists who had given some help to my father, the mayor, the local rabbi, and a reporter from the Kimberley daily.

“Jabotinsky was the first person I had ever met who had come in an airplane, but I hardly wondered at that; it seemed to me no more than fitting that he should come from the sky, in one of those planes which were then still rare enough to be stared at when they lumbered over the town. In a way, I was less impressed by the airplane than I was by the fact that the non-Jewish mayor of the town had felt himself called upon to join in the welcome to be given to our visitor.

“Jabotinsky was small; he was dressed in a grey suit with a pale stripe; he seemed calm and self-assured, and more interested in us than I had expected him to be. But what struck me most of all about him was that he had some powder on his face. It was, I suppose, some kind of talcum powder which he had put on after shaving and which he had not bothered to wipe off; but then it seemed quite mysterious to me, and not a little embarrassing. What was even more embarrassing was that the mayor could not pronounce Jabotinsky’s name. The reception took place in one of the waiting-rooms of the airport, to which my father had conducted Jabotinsky from the barrier, and the little room seemed crowded by the time the mayor began to speak. He spoke hesitantly, poorly, I thought, but he went beyond what I had thought could be Kimberley’s worst when he called Jabotinsky “Mr. Jabber—Jabber—Jabbersky” every time he had to say the name.

Page 6 of 14

Jabotinsky’s visit to Kimberley in 1938

“I didn’t know which way to look; I tried particularly to avoid meeting the eyes of my brothers who, like myself, were scrubbed, combed, and in their best suits. But eventually I looked at Jabotinsky. To my surprise, he seemed undismayed at what the mayor was calling him; he stood calmly and gravely, his head inclined a little, listening to what was being said. Then in reply he spoke a few words; I can’t remember what they were, but I do remember feeling a little disappointed because he spoke with a “foreign” accent, like any other Jew of his age. I believed that all Jews who were not of my generation spoke like “foreigners,” but I was expecting Jabotinsky to be remarkable in every respect. He was not in this one.

“In what other respects he may have been remarkable, I can’t tell from my single meeting with him, for my memories of what passed after the reception at the airport are vague and disordered. I think that after the strain of meeting the visitor I became bored and overwhelmed, and as a result was able to take in little of what was happening around me. I know that my elder brother was so overwhelmed that no sooner did we get home than he climbed on his bicycle and simply rode away. Lunch was delayed in expectation of his return; but we ate the meal with an empty place at the table. I can remember Jabotinsky inquiring just before he left the house about my brother, and my mother assuring Jabotinsky that she was not worried, and was sure her son would be back. He was, at dusk, exhausted after his ride, and ravenously hungry.

“Of the lunch the only vivid recollection I have is the expression on my father’s face when John served up the dessert in the wrong bowls. Later in the afternoon my father took down the photograph of Jabotinsky which hung in our living room, and removed it from its frame; Jabotinsky then inscribed the photograph in a beautifully neat hand. And for the rest I remember the unfamiliarity of the house, with its shining stoep and garden path, the servants glistening in their starched whites, and the talk and the smoke and the bottles and glasses in the living room, where the grown-ups gathered after the meal. I did not go to the meeting in the evening, and I did not see Jabotinsky again, after he had left the house. The meeting, I gathered the next day, had been extremely successful. Jabotinsky’s name had been sufficient of a draw to more than fill the Town Hall with Jews and Gentiles, and my father was glad that he had charged an admission fee, to go to New Zionist funds, though others had advised him against it.

Page 7 of 14

Jabotinsky’s visit to Kimberley in 1938

“But Jabotinsky spent a longer time in Kimberley than he had planned to. Or rather, he spent the time near Kimberley. For after the meeting in the Town Hall he declared that he did not want to go to Cape Town the next day; he had no meeting to address there for a couple of days, and no appointments of any importance, and he thought that this would be a good opportunity for him to rest. My father, I understood, had offered him the use of our house, if he wished to leave the hotel; but Jabotinsky had declined the offer. What he wanted, he said, was to be alone, quite alone, in a small place where there would be no one at all who knew him. He wanted, he said, “to think,” “to ponder on certain matters”; he wanted “two days of solitary reflection.”

“To me the request seemed all that might be expected of a great man; it had an imperious, poetic air about it which I much admired. But my father was disconcerted; he did not understand the request, and I don’t think he altogether believed in its necessity. I could not then see the reasons for my father’s disapproval, but I do now. I believe he suspected Jabotinsky, his hero, his one great man, of being a little moody, a little sulky or contrary; of being determined to show his differentness from everyone who did not need two days for “solitary reflection.” And as a result of the change in schedule, my father had to do much telephoning and telegraphing to Cape Town and Johannesburg.

“For his two days of solitary reflection, Jabotinsky went to a little village, Barkly West, which had once been famous as the scene of the country’s first great diamond rush. Barkly West is about twenty miles from Kimberley. For a South African dorp it is an oddly cramped little place, though it has a fine view across the Vaal river, with the rocks in the river-bed shining in the sunlight and a trickle of dark green water running between them. Along the banks of the river, for a distance of many miles, the ground was turned over into heaps by the diamond diggers, during the late 1860’s; some of these artificial hillocks are still bald, others are covered with a thin growth of grass and low camelthorn trees. But for the miles upon miles of these abandoned mounds, there is hardly any sign of human achievement around Barkly West; the veld stretches uncultivated to the horizon, on all sides.

There, for two days, Jabotinsky reflected.

“Time destroys us all and forgets us all; but it never releases the living from the compulsion to act. Jabotinsky must already have been a very sick man during his visit to Kimberley; he had really needed that rest in Barkly West, though he had been unwilling to admit (perhaps even to himself) why he had needed it. Two years later he was dead; of a heart attack, in New York.

Page 8 of 14

Jabotinsky’s visit to Kimberley in 1938

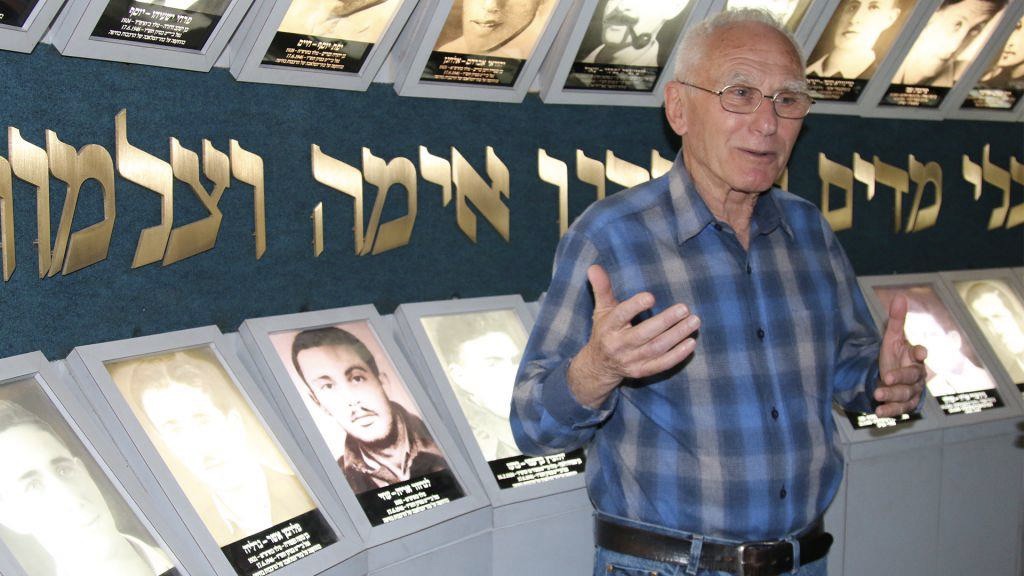

Irgun Museum

Dan continued: “Last year (1960) I went with my father, who is now in his middle seventies, to Israel. One of the things we did while we were there was to pay a visit to the museum, run by an Israeli political party, which records the struggle of the Irgun Zvai Leumi against the British mandatory regime.

A room in the museum is set aside for relics of Vladimir Jabotinsky, for it was to him, even after his death in 1940, that the Irgun looked for inspiration. In the Jabotinsky room there are manuscripts, many photographs (one of them an enlarged copy of the photograph which had hung in our living room); in a glass case there is the uniform and ceremonial sword Jabotinsky had worn as an officer in the British army during World War I.

In the largest room there was the commemorative exhibition of the terrorist campaign, and memorials to the men who had taken part in it. There were photographs of the buildings the Irgun had blown up; models of the explosive devices which had been used; photographs of the young and middle-aged men who had lost their lives in the campaign, either in street fighting or by being hanged by the British. There was a knotted hangman’s rope draped across one board; suspended from another was the collarless overall which the men had worn on the scaffold. Diffidently, proudly, or solemnly, the men in the photographs stared across these ghastly exhibits to others less ghastly. To the photographs of a crowd of people with shocked faces staring at rubble and a corpse in the street; of illegal immigrants penned behind barbed wire on a tramp steamer; of a man being carried away by two of his fellows, his backside torn open by gunfire.

Page 9 of 14

Jabotinsky’s visit to Kimberley in 1938

The worst that Jabotinsky had prophesied for Europe had come about; the wars he had anticipated in Palestine had been fought—and won. The State, for whose realization he had expended his life, was in existence. And the museum was deserted. The whole time we were there, only one other visitor wandered into it, a bored, lonely girl with a dissatisfied expression on her face; she looked as though she were passing the time while waiting for her date to arrive. And who could be anything but glad that the people outside avoided the place, with the smell of dust heavy within it and the horrors on display on its walls? The people outside had other things to do, other interests to follow, their own lives to live. And there was no irony in the reflection that that, just that, was Jabotinsky’s reward, the only certain vindication that anyone could offer on his behalf.

Tour guide Moshe Ben Yehuda speaks at the Lehi Museum in Tel Aviv. (Shmuel Bar-Am)

As we came out of the museum, it was not just the glaring sunlight and the hooting traffic which dazed and assailed me; it was my own ignorance. I remembered the visit of the great man of my childhood to Kimberley; I remembered my own incomprehension as to what the visit had been about. How much more, how much better, did I comprehend now? I knew at least what I had not known then: that time passes; that men act; that out of their acts a history is made. But to what purpose it was that we were hurled vertiginously through time and history, I knew as little as I had known in Kimberley, when I had stared in wonder and embarrassment at a small grey bespectacled man with powder on his checks and a respectful tilt of the head toward the strangers who had gathered to meet him

Dan Jacobson May 1961.

Page 10 of 14

Jabotinsky’s visit to Kimberley in 1938

Jabotinskys Legacy?

Both a nationalist and a liberal, Jabotinsky dreamed of establishing a modern Jewish state based on, and with the help of, the British Empire. However, in response to British restrictions on immigration to Palestine, Jabotinsky proposed a plan for an armed Jewish revolt in Palestine. The outbreak of World War II temporarily put an end to these plans. Despite nationalist tendencies, Jabotinsky firmly believed that while the state should provide, it should not interfere with its citizens nor impose itself on civil liberties. “Every man is King,” Jabotinsky famously wrote.

The revival of modern Hebrew, social justice and democracy are all values that Jabotinsky fought for, and can now be found in modern Israeli society. The legacy of Jabotinsky can still be found in Israeli politics, too. The political party, Herut, founded by Jabotinsky’s protégé Menachem Begin, merged with the Likud in 1973, which has since been Israel’s largest party on the Centre-Right, ruling since 2009.

When Jabotinsky died of a heart attack in New York in August 1940, while visiting a Betar defence camp, he was interred in New Montefiore Cemetery. In accordance with his Will, it was not until after the establishment of the State of Israel that Jabotinsky’s remains were transferred to Israel.

Prime Minister Levi Eshkol organized the transfer of his remains in 1964, and ever since then, Jabotinsky lies in the cemetery on Mount Herzl. Jabotinsky Day is commemorated on the Hebrew date of Jabotinsky’s death. The day was enshrined into Israeli law on March 23, 2005, when the Knesset enacted the Jabotinsky Law “to instill for generations the vision, legacy and work of Ze’ev Jabotinsky, to mark his memory and to bring about the education of future generations and to shape the State of Israel, its institutions, its objectives and its character in accordance with its Zionist vision.”

A state memorial service is held every year at the Ze’ev Jabotinsky Tomb on Mount Herzl. On Thursday, the event will be attended by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and President Reuven Rivlin. The Knesset also holds a special hearing to commemorate the day and IDF bases throughout the country also hold lectures and services to mark the occasion.

Sometimes it felt as if every decision taken by the official Zionist movement was agreed upon by all who believed in Zionism. However, there was one leader of the Zionist movement who took a stand for what he believed, even when unpopular. He stood up for his beliefs and did

Page 11 of 14

Jabotinsky’s visit to Kimberley in 1938

not get swept up in what was “trendy” at the time. With dignity and respect, he was able to criticize the faltering leadership of those days while warning them of the consequences of relinquishing parts of the Land of Israel. He was a vigorous and enthusiastic young man who admired Theodor Herzl and decided to follow in his footsteps by devoting his life to the revival of the Jewish state. This young man was Ze’ev Jabotinsky.

Jabotinsky strove to continue Herzl’s legacy and was honoured to have met him as a delegate at the Zionist Congress of 1903. While it was Jabotinsky’s first time as a delegate, it was unfortunately Herzl’s last Congress, as he unexpectedly passed away the following year.

“Herzl made a huge impression on me,” Jabotinsky wrote, “It is not an exaggeration... I felt I was truly standing before a chosen person, a prophet... and to this day it seems to me that his voice still rings in my ears when he swore in front of us all ‘If I forget the O Jerusalem.’ I believed his oath, everyone believed...”

Like Herzl, Jabotinsky suffered from public mocking at the time but was later vindicated. The Zionist leadership called him an extremist. But today, 78 years after his death, his ideas and teachings appear in school textbooks, in literature, in plays and in mainstream political discourse.

Today (2018), over 121 years since the first Zionist Congress in Basel and 70 years since Israel’s independence, we proudly look back at the amazing achievements of our country. Many of these accomplishments were achieved by people who were inspired in some way by Jabotinsky. As head of the Betar youth movement, the Union of Zionist Revisionists and co-founder of the Jewish Legion, Jabotinsky influenced many leaders over the years. Many ideas that he wrote about in the 1920s and 1930s have now come to fruition such as the concept of individual and national pride, evident in his phrase, “every individual is a king.” The revival of the Hebrew language, social justice, democratic values and self-respect which Jabotinsky pushed for, can now be found in our modern Israeli society.

In 1923, Jabotinsky’s “Iron Wall” article was published, stressing the importance of strength and deterrence in order to fulfil the rights of the Jews in their land. Those that seek to prevent the Jewish people from achieving sovereignty in their homeland, he wrote, must understand it is as futile as confronting a wall of iron.

When incitement and a denial of our very right to exist is part of daily life, it is amazing to read Jabotinsky’s words and see how applicable they still are today. He was right when he advocated a policy of “no compromise” regarding the Land of Israel, while still maintaining democratic rights and freedom of worship to all religions.

Page 12 of 14

Jabotinsky’s visit to Kimberley in 1938

Jabotinsky regarded youth education as an important component of the success of the Jewish state. Through the Betar youth movement, which is still active today, he promoted fundamental skills, education and leadership training for the next generation.

In the 78th year of his passing, Jabotinsky will continue to be an esteemed figure in the Israeli public. A new generation is promoting aliyah, Hebrew language, Jewish pride, and high-tech innovations. At the annual official ceremony in memory of the writer, poet, soldier and leader Jabotinsky. each year there is an increasing number of participants. There are veterans who served in the Irgun together with the young generation who never met him but appreciate and cherish his legacy. The nationalist spirit of Jabotinsky is still felt in Israel today. Many institutions and streets in Israel are named in his memory.

Jabotinsky was and will continue to be one of the most important leaders in the Zionist world and his writings and philosophy will continue to inspire us for many years to come.

Jabotinsky’s South African address

In 1938, Jabotinsky’s South Africa address was titled “Na’hamu, Na’hamu Ami” (“Be Ye Comforted My People”), a phrase commanding that “just at the moment of the deepest darkness the Jew should never lose his ability to see the light beyond the horizon and to give comfort to himself and to his brethren [from] that adamant faith and conviction which has been the secret of our eternal vitality.” He quoted a poet’s observation that a ship in a gale could go in either direction -- it was the set of the sail that determined the direction -- and ended with this:

I do not believe in the blackness of the horizon. I see light. I think that the good set of the sail can transform that storm into a wind of salvation and of redemption. … What did the world know about Palestine and the Jews except two things? First, that the Jews had been turned out of Palestine by force; and second, that the Jews have never ceased claiming Palestine back. … And it is not true that there is no plan and no alternative [to the hopeless, squalid depression in Jewish ranks]. The ten-year plan of transforming Palestine into something which will save us … is what we stand for.

Jabotinsky’s youth movement in Poland had about 50,000 members in 1938. Its leader was a 25-year old Jew named Menachem Begin. Ten years later -- on the day Israel was reborn and was attacked by surrounding nations -- Begin addressed his “fighting family” in the Irgun. He recalled what had happened over the prior decade:

Do you remember how we started? With what we started? You were alone and persecuted, rejected, despised and numbered with the transgressors but you fought on with deep faith and did not retreat; you were tortured but did not surrender; you were cast into prison but you did not yield; you were exiled from your country but your spirit was not crushed. … [As we fight], we shall be accompanied by the spirit of those who revived our Nation, Zev Benjamin Herzl, Max Nordau, Joseph Trumpeldor and the father of resurrected Hebrew heroism, Zev Jabotinsky.

Page 13 of 14

Jabotinsky’s visit to Kimberley in 1938

Time passes; men act; out of their acts a history is made. History has long since vindicated Jabotinsky, but Jewish historians have yet to fully and fairly restore him to the historical record

Post script –

Jabotinsky’s sword presented to PM Netanyahu

The Israel Police Education Officer said that in 1920 Zeev Jabotinsky had been arrested by British police officers in the wake of his involvement in a Jewish defence organization in Jerusalem following the riots which occurred that year. His sword was taken from him during his arrest. The sword eventually passed to a British police officer. Several years later, the officer's daughter gave the sword to British historian Martin Higgins, who specialized in the mandatory police and whose father had been a police officer himself. Higgins gave the sword to the Israel Police. The sword had previously belonged to a senior Ottoman officer and apparently came into Jabotinsky's possession during his service as an officer in the framework of the 38th Royal Fusiliers during World War I.

This story is compiled by Geraldine Auerbach MBE London March 2020

From Dan Jacobson’s description of the event and information from Milton Jawno, Natalie Sussman, Daphne Gillis, and photo from Ruth Sheer

Page 14 of 14