I was born in Lithuania, in the town of Kibart on October 23, 1920. My parents were Benjamin Feyvel and Khaya Yasven. My mother’s maiden name was Lubetzki. I was the first of three daughters, older than one sister by three years, and the other by eight years. Both of my sisters died in the Holocaust.

Kibart was a Lithuanian town on the German border. It was to a certain extent, different from other Lithuanian towns, or even Polish towns, where, according to what I have heard, the German influence was quite noticeable–especially among the Jewish population. Kibart was much cleaner and much more orderly, much more modern, than other towns, and it had aspects of technology and civilization other towns didn’t have at all. For example, almost all the homes had electricity, and the houses were tall and made of brick and stone. There were also other houses, farther out from the center of town, farmers’ homes, built of wood, and yet no matter where you were in town, you felt the cultural, orderly influence of the Germans.

The Berlin-Moscow Express train, passed through our town, it connected us with the capital city which was then Kovno. You could travel further north to Memel2. The ‘Express’ passed through once or twice a day, back and forth from Berlin to Moscow and from Moscow to Berlin. We used to visit the train station often, where we had the chance to see many famous people that were passing through the town. We were located on the German border and there was a little river that was perhaps a bit narrower than the Assi Creek that runs through my kibbutz. The Jews would smuggle in goods from Germany, where things were much cheaper than in Lithuania. They would bring clothes, shoes, and fruit from Germany into Lithuania, and then move it farther into the country —especially tropical fruit, like bananas, oranges, and grapes. These were much less expensive in Germany, and afterwards people would sell the fruit in Kovno and in other cities. Our family especially bought almost nothing in Lithuania. All the goods we purchased were from Germany. We had something called "Grenz Karten", a border pass, which gave us permission to cross the border. There were two border posts, one on the Lithuanian side, and one on the German side, with a wooden bridge between them. We would go over that bridge which was smaller than our bridge (on the kibbutz). We loved to go there in the winter, because it would get covered with ice, and people would slip on the ice. We really enjoyed watching people slip on the ice.

The people from our town could go over the border freely; because we all had the "Grenz Karte" border passes. We were able to travel with this Grenz Karte up to Stalupoenen, (Nesterov). The German border town was Eydtkuhnen, and we were able to travel freely up to Stalupoenen and, more than once, even up to Koenigsberg. Kibart was on a plain. There were forests, but quite distant from us. Further on there was a town, 4 km from us, Virbalis. Our train station, by the way, was not named after Kibart, but after Virbalis. Why - I do not know. The rails went through our town. People lived on both sides of the rails. The youth of our town congregated in the train station, and we had fun together. We also went to the town of Virbalis, where there was no train. There was a bus. The road was not made of asphalt, it was made of stones and it was not comfortable to drive there. We traveled by bus, or by train, whoever could afford it. Sometimes just for fun, we went by sled.

Kibart was about the size of Beit She’an, where my kibbutz is located. It was a small town. I do not know the number of Jews. They were not a majority. But the Jewish population was quite dominant. In addition there were Lithuanians, there were Germans, there were Russians. It was quite a colourful town.

The dominant language in the country, obviously, was Lithuanian, the official language.

Kibart Jews, like most of Lithuanian Jews, spoke Yiddish. With my parents I spoke Yiddish. There were several families who spoke German. . In my circle, the dominant language was German. All Jewish children in town, except a few who studied in the German school in Eydtkuhnen and later in the German pro-gymnasium in Kibart, studied in the Hebrew elementary school where Hebrew was taught from the first grade, so that many people in town knew Hebrew. The main occupation of the Jews was commerce, there being shops of haberdashery, grocery, shoes, cloth, paper, books, stationary, meat, iron and tools, household utensils. There were also several small factories such as bookbinding, a shoe polish and tin cans factory, several textile factories, sewing workshops etc. The workers were Lithuanians. Very few were Jews. There were many craftsmen: shoemakers, photographers, tailors, fashions, barbers etc. Some were engaged in exporting agricultural products, such as flax, after processing it, and horses for meat. Apart from those there were one cinema owner, two tavern owners, several customs clerks, teachers, bank clerks, two carriages and one taxi owner. There were people-"Couriers"-who traveled by train to Kovno every morning and returned in the evening. They passed on orders from the merchants of Kibart to the wholesalers in Kovno, and then brought the ordered goods back by themselves on the same day. They also sold smuggled merchandise from Germany to the rich merchants in Kovno, and there were seven families who made a rather a poor living from this occupation.

The Jewish youth studied. We had a Lithuanian National Government school, of course, and there was a Jewish Hebrew school. The National one was free. There was a Lithuanian Gymnasium4, a Commercial Gymnasium and a Pro-Gymnasium, i.e., four grades in German. These were Government run, although in the Gymnasium one had to pay tuition. The Jews and the poorer population, or the more Zionist studied at the Jewish school. After finishing, they went to study at Virbalis, where there was a Hebrew pro-Gymnasium.. Some furthered their studies in the Hebrew Gymnasium in Mariampol5. . Those who were more affluent, until Hitler’s rise to power in ‘33, studied in Germany, in Eydtkuhnen6, . There was an elementary school there. Later they went on to Bismark Schule, a high school..

Our Cinema showed film twice a week. There were two halls. For us as Gymnasium students, and later for the students of the Lithuanian Gymnasium, it was forbidden to go to the Cinema, until one of the teachers went and gave [his/ her] approval, then we were able to go. If he felt like disapproving, we could not go. There was no theatre, but there was an infrequent play, for instance by the Jewish theatre, which did not arrive very often. If you wished to go to the theatre, you went to Kovno. There was a Jewish theatre, and opera and ballet in Kovno. At that time they held to a high standard. On every vacation and sometimes even in between we went there to see them.

Chapter II ---Family Life

I cannot tell you about our relatives because I do not know. We lived in Lithuania. Our relatives lived in Vilna, and my parents came from Vilna. That part of the country belonged to Poland. In ‘38, Poland threatened Lithuania with force if the Lithuanians would not make peace. So we had no contact with the family. Except for the fact that father sent his parent funds. My father sent funds to my mother’s parents as well, but he made a point to support his own parents. The letters and funds went through Germany by using a "Expediter", a person who transported all sorts of packages and things like that. I did not know my grandparents. My mother was the youngest in her family. My grandfather had passed away before I was born. I was named after him. His name was Ozer, so mother made Roza out of it. My grandmother died later .My cousin told me that when the message arrived of the death, they did not know how to convey it to mother. I was probably 3 years old. I cannot remember it, but I was told that I ran joyfully to tell my mother that grandmother had passed away. My father’s mother died as did my grandfather, whom I met only in ’39. Contact between us was very little.

My aunts and uncles were all in Vilna, except for my mother’s sister in Kibart. The relationship between her and my parents was not good. Father had 3 brothers in Kovno with whom we did not have close ties. The German influence distanced us from all of these relatives.. My parents worked as traders. They were not educated, even though they came out of good homes, educated homes. Mother was the youngest daughter and she did not want to study, and they probably let her get away with it. Her older brother was a teacher in a Gymnasium in Vilna, a Jewish Gymnasium..The rest of the brothers and sisters were more or less educated. My mother was simply too lazy, she did not want to study. It was not like today. If one did not want to study, one did not have to. On my father’s side, his father was an educated Jew. But he was a hard man and not very kind. There were 16 children. He did not allow his children to study. He demanded that they go to work to support him.

Mother worked as a trader in our store. We also had a workshop for underwear. Father was like a Foreign Affairs minister. He marketed the things and mother stayed at home. The workshop was attached to the house. My sisters were all younger. We all studied. Father was very insistent that we would learn, because he had not been allowed to study. It was very painful to him. If we would bring home a bad mark, it was a tragedy. So at times there was money and sometimes there wasn’t any, but for education there was always money. On that point, my father would not give in. I finished Gymnasium before the war.

Our home was not religious. Mother kept Kosher obviously, and kept the milk and meat dishes separate. They did go to synagogue in the High Holidays, but it was definitely not a religious home. Father used to go to synagogue in the high holidays, like a good [i.e. observant] Jew. On Friday we had to come home, take our place at the table, it was a ceremonious dinner, without Kiddush, but on Saturdays, we went to school so the parents waited for us with the meal. Obviously, they did not work on Saturday, but it was not a religious home. Definitely not, nor a Zionistic one. For the Passover holiday everything was done just like the Jews did. There was a cupboard with dishes, you know, in Jewish homes, the Kopet, there was a special compartment with all the dishes, which were kept Kosher for Passover and mother boiled the dishes that would have been used, since they were the same everyday ones. Mother went to Padrat, where they used to bake the Matsoth. They were not factory made Matsoth,. Mother ordered Matsoth. Padrat. . Mother used to go there and bake, or order, to be exact, ‘Eier Matses’[i.e. Egg-based Matsoth].. And of course, mother made wine of raisins, with hopfen [i.e. hops].

They used to make everything that was needed for the Passover Seder. Father used to hold the Seder as well. It was obviously not a very impressive Seder. We did not have other relatives who came, only the close family. We were not very religious. What is more, if I tell you why we were happy when Rosh Hashanah came you would be amazed, because on Rosh Hashanah we received new clothes. So we waited for the weather to become cold and not rainy, so one could wear the new dress, and the new shoes. At Khanukah they used to light the Menorah but it was nothing special. It used to overlap with Christmas, and that holiday impressed me more. We visited the homes of Christians. Most of my girlfriends were Christian. Our family observed only [the fast of] the 9th of Av. We knew we had to put on a handkerchief on our head.

Chapter III —Education

I began school when I was 6. I went to the National German school in our town and there I studied for a year. Some time later, the Jews like everywhere else, suddenly woke up and started crying out, why had I been studying in a German school? In our town the Jews did not study in the German school. And then there was a period in which I did not go to school .I received private lessons and it was recommended that I go directly into the next grade in the German Pro-Gymnasium. There no one intervened, because father had paid for it. There were no Jews studying there at all. I was the only one. It was a small school. Jews studied at Eydtkuhnen. That was in ‘33. Now take into account, I began my studies in ‘26. In ‘33 Hitler came to power. Jewish children of our town were transferred from the German school in Eydtkuhnen. Some of them were transferred to our school, the German [one], some went to Virbalis, to the Jewish Pro-Gymnasium. Because it had only 4 grades, we moved on to the Lithuanian Gymnasium. Others continued in the Jewish Gymnasium in Mariampol.

There were 4 grades in the National school and 4 in the Pro-Gymnasium. I finished all 8 in the German school. I went on for 4 years in the Lithuanian Gymnasium. The teachers were mostly Germans, except for the Lithuanian language teacher. Since it was a College Gymnasium, we had an accounting teacher, and studied accounting -- Komerz Rechnen, today it is probably not in fashion because you have computers. So there was this [accounting] teacher and he was also Lithuanian. They brought in a Jewish teacher to teach us religion, but we got rid of him very fast. There were already Jews [in that Gymnasium] so they thought that we needed to study Jewish religion as well. But who wanted to sit after classes and study the Jewish religion[?] We started to harass him [i.e. the religion teacher], to sew his coat [together], we gave him some sneezing powder, and all sorts of trouble. We quickly got rid of him. It was a school for boys and girls.

There were youth movements, but I did not belong. My father did not agree. There were scouts, there was a revisionist movement, quite a large one. If the Zionist youth organizations were there, I do not remember. Probably they were, I just never met with them. My area was Gentile. My girlfriends were Gentiles.

There was no separation in town. In the same house Gentiles and Jews lived together. And further into town, where it was more rural, with farmers, there were less Jews there. But where we lived, in the more affluent area, let’s say it was mixed. There were Lithuanians and Russians and Germans all in one house. There were no problems.

After school, you did homework of course, and played [an instrument]. I was lazy and my mother was not on my case, so I did not play. . I almost did not go on trips because father would not let me. Father was not [really] so strict, he was simply afraid, so I did not take part in trips. Later, I joined the Lithuanian Scouts, the Gentile ones. That was much later. I was in the same school until ’34. Then I went to the Lithuanian school, in town, and finished Gymnasium, until matriculation.

After Hitler’s rise to power, the Germans still used to come to our town. We always recognized the Germans due to the fact they always bought and ate a sausage. In Germany the meat was more expensive, so they came to Lithuania and ate a sausage. There were Jews there and what one did feel, was the shunning of Jews in Germany [i.e. by German Jews], when we went there, "Ost Juden" [i.e. Eastern Jewry]7. The fact that they came later to our side [of the border], that did not matter anymore. They created a distinction that we are after all, Ost Juden. [They disregarded] the fact that we did not have less culture than they did. Well! If you are asking me about the later part of growing up! There were probably guys who belonged to Zionist youth movements, I did not know. But I knew we were quite a small, close group, what they called "the Golden Youth". There was one guy who I was convinced was a Zionist, but when the Soviets came, it happened he was one of the Communist leaders. Only after the Soviets entered Lithuania, suddenly it was discovered there were many Communists in town.

Chapter V--- Mother’s Death

I finished gymnasium in ‘39. My mother passed away in ’38. She passed away suddenly. She was not sick. It was on the 30/12/38, on Friday evening. We had dinner, laid down to rest, mother and father had planned to go the next day to a Sylvester Party in Kovno, and mother was the last to go to bed. She still checked the house to make sure everything was closed, and about 12:00 she gave one shout and that was that. We did not know why. These days they would have checked. So, she passed away and that was that. That was half a year before the end of Gymnasium. I know that mother was expecting me to finish Gymnasium, to prepare a party and all that. But that, of course, never came to be. The house remained without a mother, it was orphaned.

We were not taught to work or to manage the house, because my father thought that he could always earn our keep. After a short while he brought in a housekeeper, who managed our house. My second sister took it very hard. She was 15, I was 18. Throughout the week of mourning, she did not sleep. We went to a Jewish female physician who gave her some sedative pills. My little sister was 10. At that time they said that a daughter until the age of 10 is allowed to say the Kadish prayer. Father could not say Kadish because he still had a father. That was the way they explained it to us. My little sister used to run 3 times a day to synagogue and we got over it, as they always do. It was hard. I finished school half a year later, took Matriculation examinations. It was a Commercial school, but it was possible to go to university without problems. They gave problems only to Jews, to those who wanted to study medicine. Most of them went to Italy to study. I did not want to study medicine. I actually wanted to be a nurse even then, but by my father it was [considered] less respectable. He said that I will study medicine. It was more of a fashion than an actual choice of studies. I went to university and studied.

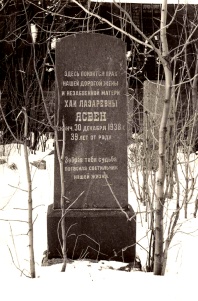

The headstone on Roza's mother's grave Inscription in Yiddish on the other side inscription in Russian

I was registered at the University in Kovno, for a humanities-based degree. It included Philology and History. Actually, war broke out before I reached the university. WWII broke out on the 1/9/39, and on that day the Academic year started.

There was a struggle between Poland and Lithuania, and then the borders opened, between Lithuania and Poland. It was the first time I met my relatives. At first, only my parents went with my sisters, I did not go. Mother still lived then. I did not go because they had to make a special passport for me. After mother died, I went there with father and the girls in ‘39, when the war broke out. It was still peaceful on our side.

We were too young to react when the war broke out. War, is war. It did not matter to us, actually. Then later, in ‘39, I began my studies in the University in Kovno. I went there to live, I had a room there. Father paid for everything. I did not have to work. At the end of the year, the Soviets gave Vilna to Lithuania. Part of the University went to Vilna and I also went there, because our faculty was transferred to Vilna. From January 1940 until the outbreak of war in Lithuania, until June 1941, I was in Vilna..

In Vilna, I met, again, with a limited circle of people that I knew. There was the group of Jewish friends that I knew from University. You see, even from the fifth grade, the entire composition of my group became different. There were already more Jews. Also at school, in the Lithuanian Gymnasium there were more Jews. They were still mixed with Lithuanians, but I gradually distanced myself from [their] company. Why? I do not know. It was just a kind of process, for no reason. I simply became close with Jews and distanced myself from Gentiles. Although, I did have Gentile friends.

In our town again, if one goes back in time a bit, there was a great synagogue, and a small synagogue. What was the difference, I do not know. Then there was the Catholic Church, there was the Provoslavic Church, there was the Protestant Church, and since the Protestants have all sorts of sects, there was the Methodist Church, there was the Baptist Church; I actually visited all the churches. I liked going to the churches, especially on their holidays. Father did not care. I was too afraid to go to the Provoslavic Church, because of the pictures there. But I really liked going, especially on Easter, to the Catholic Church. It was very pretty. I was not the only one. We all did it. We did not have a separation. We [just] went. For instance, in Passover we brought our Gentile friends Matsoth, and whatever they liked, and on Christmas we went to visit them, to see their Christmas tree. There was no separation.

In Vilna, I simply met students there, not Poles, because actually, what really had rooted deep inside, was hatred towards the Poles. Because it was the way we were taught. They were our most hated enemy. So in Vilna I still had my friends, or girl buddies, since we came from the same town. It was a Lithuanian university, but there were Jews whom I met. There was a certain group of friends to which I belonged. I had girl buddies who had relatives there [who were] younger. I came into contact with the Polish refugees for the first time. Also, with much more educated people. There was a dentist there, a musician, and older people. We met at my friends’ and relatives’ homes. Obviously, I saw my own family as well, but somewhat less, because they were all either older than I, or younger. None were my age. And I did not live at their place. Father paid the rent for my room in the students’ dormitory. I had the financial opportunity to live well.

In Vilna, in our free time, we took advantage of the city, its theatre, opera, and concerts. We went to many concerts. I had a friend there who played in the Philharmonic Orchestra. He took me with him time and again. Of course, there were studies, and preparations for exams, and that took most of [our] time. To be honest, when I was young, I wasted quite a bit of [my] time, on nothing. I did not have anything to do. I went to night clubs. We had fun dancing at balls. [But] not in [our] town. In [our] town we met at private homes. We used to meet and dance, especially in Kovno. I went to the opera every time I could. [I went] to the ballets, and concerts. I almost never went to the Jewish Theatre. There was no Lithuanian theatre, or it was not up to standard. We went on many outings.

Chapter VII ---Refugees

I will speak about the refugees who came from Poland. In our town, for a short time, there were a few ‘Khaluts’ movement members, [with] a bit of training. People felt really sorry for them. Those were miserable, poor people, I had no contact with them. Then, when the refugees came from Poland to Vilna, but for that I have to go back, [because] there was this very interesting period, which might be very important. It was the period in which the Jews fled Germany. [As] I have said, the Express train ran through our town.

These refugees from Germany began to flee, before the war, in ’35. They came to Lithuania and the first stop was our town. I have to praise my father, because he helped them a lot. He hid them at the house. It was a fact that he risked himself and us, because after all, it was forbidden. Had they caught him, he would have been thrown in jail. It wasn’t allowed for refugees to enter Lithuania. Lithuania didn’t accept them. Not formally and not in our town. After all they had crossed the border illegally. So they used to hide themselves in our home. Father risked himself and us by keeping them at our workshop. In that way no one would notice them. Later on we smuggled them onwards. I remember a certain incident, amongst many, in which I was the instigator. My father and I had boarded the train. The Gendarmes8 came. I was standing at the entrance to the cabin, and the refugees sat inside and the Gendarme asked in Lithuanian, "Is everyone from [around] here?" I said: "Yes, everybody is local." And he moved on and we managed to get these people to Kovno. The moment they reached Kovno, the danger became less [substantial]. I believe they had relatives somewhere in Yurburg (?) and they continued onwards. That was one of the incidents I remember.

Then there was this other incident, involving my father. He was on the train and since he went by train a lot, he knew all the officials. He saw this refugee standing by the door, without hope. He knew that he was a Jew, [and] he said: "What’s the problem?" The man said: " I have only one option left --to jump off the train." He came from Danzig, and wanted to reach Vilna. His family was in Vilna. He had earlier been caught and sent back to Germany. So father bumped him, hugged him, started to kiss him and said: "Oh, it’s good to see you, my brother, I am very happy to see you." Father took some money from his pocket, put some Lits [i.e. Lithuanian currency] into this Gendarme’s pocket, and rescued the Jew. Later there was a recurrent thought. When I was in Russia and people were nice to me, I said that’s because of father, because he had helped the refugees a lot. That’s the thing I had to go back for.

I was a young girl and actually, I did not have any interest in outside events. I lived my own life, my glowing years, the same way that today the "golden youth" lives it. I came from a kind of youth, that did not delve deeply into all these problems. For instance, at our home [we had] two radios, because father wanted to listen to the news, and we wanted to listen to dance music and to dance. We had faucets and water pipes and toilets at home and electrical appliances, an electric oven, an electric iron, we had all the advantages of technology at that time. These were my surroundings until the war.

Chapter VIII---More about Vilna

In Vilna I met a few Jews. The refugees were there. Their problem was with the language. The refugees did not study at the university. They spoke Yiddish. I let them speak, [and] speak, and towards the end I used to say (in Yiddish): " Excuse me, what did you say?" I could not understand the Poles’ Yiddish. But, that was also, a very short period.

Then WWII started. I was in Vilna for a year and a half. I lived on Shopin Street. I completed university [studies] in history and languages, German and English. In Lithuania the schools were divided into specialities. The Jewish ones as well. For instance, in Kovno there was a "Yiddishe Komerz Gymnasium" [i.e. the Jewish Commercial High School]. It was the equivalent to our Lithuanian school. But there were those who belonged to Schwabes and there was also the "Yiddishe Real Gymnasium".

In Kovno there were two Jewish Gymnasiums, a Russian Gymnasium, a German Gymnasium and obviously, Lithuanian Gymnasium. In the Gymnasiums that had human sciences they studied Latin and French and those that had mathematical sciences, had more math and English and English as a third language because the Lithuanian and German languages were mandatory.

Chapter VIII–Soviets Arrive

The Soviets entered in the summer, in 1940. They liberated Lithuania and all the Baltics. In the beginning one could not say that there was a big change. We received them very positively. To tell you the truth, I was not really into politics. I was quite distanced from politics and for me, Communism was a very scary thing, for which one would have been sent to prison. The 1st of May was always a very scary thing and we feared all the demonstrations, the detentions, the police etc. And at some point it was scary. But to tell you the truth I was not into it. Now, it appeared that the Soviets are not that bad, what went on inside the U.S.S.R, those who were into it did not know, I definitely did not know. Slowly it dawned on us that one could not continue to live like we used to. Father was no longer a workshop manager, he was just a tailor. We went down a step. All in all we had a bourgeois home, but when the Soviets came, we tried somehow to lower the standard, as if we belonged more to the Proletariat. We did not know the Soviets. You were actually disappointed when you saw them.

The lines for food began here and there because the Soviets ransacked everything. Then began, I think it was Nationalization of property. The students had to take part. We were sent to the stores. I remember myself in one of the stores. We counted the stock. I did not understand much of it, but it made quite an impression. I did not understand what this meant, what it actually added up to. I remember there were two or three days that we sat and we counted the stock and it became state property. They transferred the stock to the government. I cannot remember the name of the store. This was not just the stores of the Jews. All stores. But, since most of the traders were Jews, it probably hit the Jews harder. What could they say? Do?

They treated us well, courteously. But we did not have a choice. What they were thinking, it’s hard to say. Because I can imagine that my father also had great fears. It reached us much later, to my misfortune, it reached us too late. Because had they arrived a week earlier, the family would not have gone. Later I decided, even though I did not have to, that it would be beneficial to go and work. And I knew accounting from school, when I was still in Kovno. I decided to take a typing course on a typing machine. Just like that for no reason, but I decided to do it. So I got a job placement in accounting. It was in a wood factory, with many workers. The funny thing was that they had a hard job and they felt sorry for me, poor me. I had to sit there all day to manage accounts and to type. I did all that only for appearances, not to stick out of the crowd, as if I belonged to the bourgeois. I went home of course, every once a while.

The situation at home was normal. The Soviets were already there and actually everything worked as it always had. A week before the outbreak of war, in June ‘41, we had to get Soviet Identity Documents. For some reason we did not want to do this, but I cannot remember why. I received a telegram from father to my factory, [saying] that I must come home quickly. I was a good actress. I got tears in my eyes because of what happened at home. But it was all [pre] arranged with father that I would receive this telegram on a Friday. I went home. On the days following, the transports to the U.S.S.R. began for those who were wealthy. Father came home very frightened and said I had to go back to Vilna. He said our family would not go to the U.S.S.R. because it might be that we would not be allowed to stay. I went back to Vilna.

Chapter IX --- June 22, The Germans Attack, War Begins

My family at that point consisted of my two sisters, father, and the housekeeper. The war started on Sunday, the 21st of June. Father happened to be in Vilna. We heard aeroplanes, we heard sirens, but we thought they were drills. I went to a meeting at around 10:00. It was a beautiful summer day, truly amazing, and I met father. He told me that war broke out, I said: "Nonsense, it’s just drills." He said: "No, it is War", and I should stay in Vilna, that I must not leave the place.

He goes home and he thinks that the safest place for us would be in Kibart, in our town, where our friends were, until the end of the war, as long as it takes. There is no place like home. He goes home and tells me that I must not leave this place. At this time I was staying with a woman. We had spent the night in the basement. We decided to run away. If you’d ask me why I decided to run, I don’t know. It was some sort of instinct. I don’t know. I cannot explain. We did not know what to take with us. We took two big suitcases. Everything went missing on the run, a lot of money and jewelery also went missing. We went to the Vilna train station and sat at the eshalon the whole day.

People knew that the Germans had attacked, but they still could not comprehend, they could not grasp what went on. We were not bombed on the first day. The next day, I sat all day in the train station. Father came to my dormitory, saw that I had run away, and looked for me in the train station but he could not find me. He went through the entire eshalon and could not find me. He would have taken me off, and I would have gone with him without a word.

Chapter X---Roza becomes a Refugee

And so we began our journey. The train began to move. We thought that we would reach Minsk and tomorrow or the day after the war would end and we would be able to go home. The people on the train were all sorts, not just Jews--Communists, especially the Soviets, and those who worked for the Soviets. We traveled up to the old border. In another cabin, I saw a family which included girls who were friends of mine. I was not very wise then, well, the wisdom was not there. We were quite innocent. We made plans to meet in Minsk. Later, much later, I got in contact with them through Bogoroslan10. We reached the old border and they took off all the people who came from Lithuania and western Poland. The train went on with the Communists and with the Soviets and we were left next to the border. Where, I do not really remember. Just in a field. And here began a period in which I do not remember where the places were.

At night we crossed the border and kept going, in a disorganized manner. There were always groups that came together and broke off, and again came together. Some people became separated. Although I was with that woman I was actually alone. We were not really together. We managed to board the train and ride a bit and reached Vitebsk. Near Vitebsk the train was bombed. Some people were killed. We did not even look, just kept going. I cannot really describe that because I don’t remember. I only know we reached Mogilov11, and a family of two elderly Jews had us as their guests. I still remember that the woman gave us verni2 i.e.jam. She said inYiddish: children eat, I know what goes on with my children. We went on to Orsha and were held there. People fed us on the way.

After carrying the suitcase, I slowly threw things away, until I was left with nothing. I also did not have the brains. My money and jewelery were stolen. I got to where I had nothing basically, only a dress and a pair of underwear. When we reached Orsha, they held us, incarcerated us, in the police [station] for whole day, and then they let us go. They thought we were spies, and all that, it was a huge mess. It was what you see in the movies. The one where people run and you walk and they bombard you. And you lie in the ditches. You always hide your head in an instinctive manner and when it’s over, you go on walking. There were many incidents. Once we were in some kind of a Russian village and slept there. A peasant’s wife came and told us: Jews, get out of here very fast, because the Germans are one or two kilometres from here. This happened more than once that we faced these kinds of risks.

We were once surrounded by Germans on three sides. Somehow we managed to escape, we always managed to escape. People assisted us. One helped another. I remember that there was one place where I said to the guys: enough, I can’t [go on] anymore, you go on, I’m staying here. I can’t go on anymore. My feet ached, there was no strength left. So two guys got me up. Someone picked up what was left of my things. They dragged me a few metres and I was able to go on with them. They did not leave me behind. For two weeks, we went like that on foot.

We reached a forest and found potatoes, and cooked them. Someone said: put the peels in as well, [this way] there would be more [to eat]. By this time I had head lice. I had long hair then. We decided to have a haircut, get the hair off. Who even knew how to deal with head lice? The lice were already in the clothes. I thought if I could wash the dress in the river, then I would get rid of the lice. But the Germans started to bombard us again. Somehow we made it.

By the time I reached Veliki Luky I had no shoes. I had swollen feet [to such an extent] that I could hardly walk. The authorities put us on the train and gave us food.

The train took us to Kazan15. There was water in the train station. Whoever had some money left or some clothes, exchanged them for food. Peasants used to sell all sorts of things near the train station. Anyway they gave us [some]. The authorities were already taking care of our needs, such as bread and things like that. I do not remember these things very well. I’m sorry, it took a lot of time, but here begins a period of...

We were refugees. They already recognized us as being refugees. There is one thing I forgot to mention . Perhaps it is an interesting and important thing, we had to cross the Berezina river. The Berezina16 is also known from the Napoleonic wars. (I can remember the past.). In White Russia [i.e. Belarus] the Soviet army was in retreat, but an uncoordinated retreat.

At the ferry on the river, those who operated it did not want to take us refugees. A Soviet officer brought his gun out and said: "Either you bring everyone across, or I’ll shoot you." And then they brought all the refugees across the Berezina. With the same officer there was another incident. We lodged in a house in one of the villages. A young woman was there, and another woman stole her money. In the morning the young woman cried, she does not have any money, what will she do - no one knows where the money is. The officer called the child of that other woman, that peasant woman, took the child aside and told him: tell me where your mother hid the money. The child told him and he gave it back to the young woman.

I met, I think, with thousands of people. [But] I remember that Soviet officer. If there is something out of the ordinary, I remember. Another incident occurred as we were walking. Towards us came the Red Army. And there was this Jewish soldier who saw us. He told us: "I do not know if we are in the process of retreat, or if we are moving back to regroup. Follow our lead. If we are coming back, go with us. If we would not be back continue with us, we will make do. Then there may be Germans." So we stopped and when we saw that the army did not return, we went on.. But this is all in episodes in my memory, things that I can remember time and again. Had I written a diary, it would have been lost as well. Now after so many years and after all that has happened, it is hard to remember all those things chronologically.

I was with that friend all that time until we reached Kazan. That is the capital of the Tatar Republic. The authorities began to send us to Kolkhozes,. (Collective Farms) We traveled over the Kama17, the river Kama, and reached Chistopol. We were in a city, Chistopol18. We were interviewed and transferred us to Kolkohzes. Now, go figure what’s a Kolkhoz. (Collective farms).

Initially we were received with open arms. The Government handled all this. I can’t remember specifics. I just know that they sent us up. I do not think they registered us. Maybe they did I do not remember. I just know that I got to a Kurgaly, an interview, and from there they sent us to the many farms. I got to a Kolkhoz. Other girls came, I think from Latvia. They were registered nurses. They knew how to work and it was easier for them. The Tatars received them well. I, who definitely did not know how to work, had it very hard. We were sent to work in the field. Who on earth knows how to work in the field? I was assigned to work with a Tatar woman. I lived at her place. The situation was so bad, [that] I used to steal the food that she prepared for her cat.

My friend was there and also this Russian girl. I’m trying to remember who she was, but I do not know. Later they said that she had been a spy. She lived well, in good conditions and she had money..

My friend and I spoke Lithuanian, because we did not dare to speak German. My friend was also from my town. But we did not dare to speak German. I remember this part vaguely. I went somewhere with some other woman and when I returned, my friend had gone with that woman. She left. I do not know where and I have not seen her since. She left without saying goodbye. Nothing. I came back, went some place, do not know where, and could not find her again. I was left alone there.

I had to work in the field. But I did not do anything. I did not know how to work. It was very hard for me. Not even at the house, and the Tatar woman tried to get rid of me. Anyway, one bright morning I decided to leave the Kolkhoz and went to Kurgaly. I went to Raykom, the local government, which arranged for me to live with a Tatar [family] in town. I started to look for work. I came to the manager of the Raykom, (region council) and he suggested that I go and work in floor cleaning, house cleaning. It is not that I did not want to, I simply did not know how and said no. I received food from the authorities. I lived at the Tatars until one day the Tatar woman threw me out. The Tatars have a method in saying something bad. They always say it in the morning. The Tatar woman wanted me to help her with cleaning the house. I tried to wash the floor. I did not know how to wash the floor, so she told me that she cannot have me there, that she does not have any room and that I should leave. She threw me out.

There was a Jewish family from Leningrad in that town. They were refugees from Leningrad, a husband and wife. She was called Roza , and he was called Aharon. They were called the Barbanel (Abarbanel ?)family. There was also a grandmother, the wife’s mother, and a son age 4. I remember standing in a store and saying, "I have nothing else to do, I think I’ll go and lie under a bridge and end it all, because I have nowhere to be. The Tatar woman threw me out." Roza, the wife, hears me and comes home and tells it to her husband. When he heard that, he said: "How could you leave her? Come let’s look for her and bring her here." They found me and took care of me. I lived with them for a year.

During that year I managed to get work in soshrotobot, assisting an accountant. The salary was not much, and I did not have coupons, but I got 0.5 kilogram of bread at work. After work when I got back home, the Babushka18 always left me some food. I felt uncomfortable, but I did not have a choice. There I learned how to work a bit and helped them to clean the house and fetch water. I used to go and fetch water, with the two karamisel, and I helped, as much as I could. That family helped me a lot. He worked for a living. Then he was taken to Rabochi (labor) Battalion, but he came back.

As I have mentioned I was innocent. There was one thing I did not understand and only got to grips with it much later. It was that the wife did not always treat me very well. I did not know why, because he treated me well. It became obvious: Married men were taboo. The wife was scared and she was probably jealous of me. She had some kind of fear that I would take her husband [away], because he treated me well. So she gave me the shoulder time and again. But in spite of this, I have this family to thank for staying alive.

And time and again, as I have mentioned several times, when people helped me, I thought that it was all because of father, that in his time he had helped people. I was with this family for a whole year and eventually, when the wife saw that I would not even come close to her husband and that she does not have anything to fear she treated me like a sister.

Chapter XI---Roza joins the Russian Army

I was determined if I could not manage to reach the West, I would stay in Russia for the rest of my life. While I did not know how others felt, I was certain that the Russians would win. In 1942, the Russian Army began to recruit women. I decided, I’m going to join the army. With the army I’ll advance towards the West. I need to get closer to the West. Now, how do you get into the army, I was Zapadnaya20, I was from the Baltics, and the Baltics - that was Zapad - the West. So I decided to go to the Komsomol [i.e. the youth brigades]. I applied to get into the Komsomol . Two people there helped and supported me. I was 21 and was accepted to the Komsomol and as a person who belonged to a Komsomol, I was accepted into the army.

I was not in a Komsomol. I just took the [membership] card. I did not participate. I did not even manage to be there with the youth. The only importance in being accepted into the Komsomol was that it allowed me to be accepted into the army. What went on in the

Komsomol, I do not know. It also did not particularly interest me. With all my innocence, and I was innocent, with more luck than brains, no harm came to me during the entire 4 years of war. But I had enough brains to keep focused on my plan to advance towards the West. Otherwise I would not leave the U.S.S.R.

There was a recruitment drive. I went Dobrovolno, i.e., I volunteered. We went through all sorts of checks, health-wise. I did not have any faults and I learnt Russian pretty quickly. When I came to the U.S.S.R I did not know Russian, but I have a knack for languages. Throughout the year in which I was with that family in Leningrad, people did not believe that I was not Russian, that I was not U.S.S.R-born. There were those who thought that I had come from Moscow. In the beginning I appeared as a Jew. I did not have any identity documents. Everything was lost during the travels. My bag and my identity documents and all the family pictures were gone. I do not have a family picture, except for the one father gave me later. Everything was stolen from me. The only thing I was left with was my student card from the university. I had it until I got to Poland and it remained there in Krosno with Ben.

At this recruitment drive, I volunteered and passed . My glasses were broken. I was left without glasses, which I had worn since I was 15. Until then I did not wear them, and I did not wear them permanently after that. Somehow I managed to overcome it.

The family with whom I stayed did not know that I had volunteered. They put pressure on me not to go. [They said] — "Why would you go to the army, have you lost your mind, don’t you have anything better to do? Tell them that you are short sighted, so they would not accept you." They did not know that I volunteered in order to get on with my plan, that I wanted to move on. I enlisted and was accepted into the army. We were taken to Voronezh22. It was two days before the Germans conquered Voronezh in ‘42, and we ran away from Voronezh. We did not even manage to get our uniforms. For part of the way, we were transported, but most of the way from Voronezh we went on foot. That was the way of the army. Barefoot. Because we did not have any shoes. We had not received our uniforms. We were in our civilian clothing. Some had shoes. It was in the end of the summer and we walked a lot. There was a lot of disease and cases of dysentery. It was a very hard time. We walked in an orderly manner. I even remember that they took us to a Turkish bath. We marched in a single file like soldiers do.

I remember that people walked by and looked at us: poor things, so young and already prisoners. They thought we were prisoners. We were with officers, it was a standing army. Only the commanders were in uniform. From Voronezh we marched to Saratov23. We were supplied with food as much as was possible. In Saratov we [actually] were [in the city]. Usually we had to set camp in the forests, in tents. In Saratov we were issued shoes. After getting used to walking barefoot, it was impossible to put them on. We actually got good shoes, light, pretty, whole shoes. Later we received much worse shoes. And I remember that we did attend lessons.. The Army kept the girls separate. The whole time the girls lived apart and the men lived apart. When we sat down to rest, or in lessons, the first thing we did, was to take off the shoes.

We were in the Aerosteleni Battalion. We worked with lighter-than-air balloons. They were like a Zeppelin, a big balloon filled with Helium. Helium of course is lighter than air. For instance, in Moscow they lifted them off, because they used the balloons to deter the aeroplanes. The aeroplanes would get caught in their cables. The balloons were a sort of snare for aeroplanes. We filled the balloons with helium and folded them and prepared the balloons. The battalion had quotas to be filled. At that time we already had uniforms . We received skirts and shirts, and a Pilotka24, later they replaced them with Barrettes, and of course the belt. Later, in the winter, with Shinels and Ushamki. We went into the town, but lived in the forest, in tents and Zemliankas (houses in the ground).

I was not there for a long period. I was transferred to an anti aircraft unit and here begins a period that I cannot remember. There was a period in which I was in all sorts of places, which seem to appear like photographs in my mind, but I simply cannot make the connection between all those places and the periods of time and what I was doing there. How I got there, I cannot remember. We went through many places. We went up to the German Volga, up to Kazakhstan. Those were very hard times, in which we were very hungry.

But that was a period where I don’t remember much. I do remember two things. I had fever and was hospitalized for a few days and asked them to release me. A Jewish female doctor tried to convince me to stay. She said: "What’s the rush, why are you sitting on needles?" There was one thing that I will always remember and recounted it many a time. We stood on guard with the Vintovka (gun), as if it helped in any way. It was winter and warm clothes I did not have. I had only felt boots which were dried next to the heater. So one [boot] burnt, and I went with a grey one and a black one. It was a very hard time, for the army as well. In early ‘43, it was probably all happening away from the front. On the front, the conditions were probably much better.

I always tell [the story how], how I stood on guard once and an elderly Jew passed through. He had come from Belarus when he saw me standing [guard]. He said [something] like that: "Yiddishe Kind?" [Jewish child?] I answer him: "Yo". [He said] - "Du wilst essen? Bist hungerik? [Do you want to eat? Are you hungry?]" I told him: "Yes." He told me: "I live over there. When you finish your guard duty come to my place." So I came to his place and he prepared the food, table, a very meaty cabbage soup. He was probably a butcher. I ate with him from a single plate, and I remember that I felt sorry that I could not eat [enough] for tomorrow as well. That Jew invited me several other times, each time he passed by me, he gave me something to eat, a piece of meat, a piece of liver. I shared with the [other] girls. We cooked them of course. It was very good. Then that Jew disappeared. I don’t know what happened. But that was one of the episodes in my life, that I always remember as good ones.

I always maintained contact through letters with the Barbanel family I lived with. They stayed at the same place and I kept in contact with them the whole time. Our intention was that if my family would not survive, then I would return to them. They were my family. They sent me money, packages time and again. I had kept in contact with them until I ran away from the army. That time was a very dark period in my life, and consciously, or subconsciously, I forgot it.

Roza in the Red Army-1945

In the army, we lived in houses, which were very close together, one next to the other, girls and soldiers. To handle an uncomfortable situation depended on the girl. It was well known that one should not mess with me. Whoever wanted to, why not. But from that point they had a great deal of respect towards me. I probably had more luck than brains, because I was very innocent. I did not have, as they do today, any sex education. It was just dumb luck that nothing happened to me all that time. Most of the girls were Russian. There was one other Jewish girl.

I did not feel any anti-semitism. Each [girl] had her own problems. I always had friends amongst them. I had close friends, not-so-close friends. There was a time when I do not remember well, a time that I probably subconsciously wanted to forget.

Our division was transferred to another place. We travelled a lot, and we were already closer to the West. The train rides, some of them, used to take weeks. My work was in Anti-aircraft. I actually belonged to Communications and Phones. The air balloons, that was over and done with. I was in anti aircraft, but belonged to Communications. From there I was transferred to another unit. I wasn’t very efficient in the army. We had it good there. The Army transferred a group of people, or they transferred me alone. I transferred to some unit and there’s a picture that pops up in my memory of a certain place, of a certain event, but there’s no connection between the two. Then we were in another place. But I cannot remember where it was exactly. But we had it good there. We had a good time, we ate well, grew potatoes, it was good. I do know that it was some kind of city. I even went to the movies there, but I cannot remember where it was.

The Stalingrad operation took place. The Army’s situation began to improve. We were hungry, very hungry. I once spoke to Aharon Shorer R.I.P, (he was an editor of a book). He said that someone wrote that they had stolen a little piece of bread from him and he cried. So I told him: don’t be so shocked, it happened to me as well. I left for myself a small piece of bread before I went to sleep and they stole it from me and I cried. That time was well before Stalingrad. Then begins a period that I do remember, in Oryol25. I went to Oryol and I was in a deteriorating mental state, in every way. Not really physical, but I was in a bad shape. One day I decided: I can’t go on like this. I have to start taking care of myself. I was very unkempt. I was full of head lice. There was a time in the army in which we did not have soap to wash ourselves. But in Oryol, we received a piece of soap for bathing. And I remember it as if it was yesterday. In Oryol, I decided: I have to live again. Because I always used to say, in Russian, that I was not alive, I simply existed. I decided: I’ll start taking care of myself. First of all, hygiene, to start. Then to get rid of the head lice, to take care of the clothes, to wash them, to iron. I received very little money, but I went to the market and bought myself perfume, and decided: I am starting to be human again, and slowly I became myself again. Of course, from all points of view, socially as well, the situation became better.

I began to comprehend that the Germans had hurt the Jews. There were Erenburg books, in which he wrote that the Germans were abusing the Jews ruthlessly. He told about Leon Blum who wrote the Germans treated him badly and they were killing the Jews. At first, I did not believe it. I thought that it was just propaganda. Until I got to Oryol. In Oryol I started to ask people The Germans have already been there, the retreat had already began. Oryol is not far from Moscow. I began to ask people, what happened to the Jews. And the answers were always evasive. They did not want to tell. So I began to believe that the articles by Erenburg were not for propagandist purposes, and that something probably did happen to the Jews. The Americans began to send food. We received clothes in an orderly manner. We became an orderly army. But we also helped ourselves.

For example, when we lived in houses and it was cold, we tore down the peasants’ toilets to get wood to heat our rooms. Once I even slept on the furnace . Petrol was used for heating. One of the girls stood guard. She spilled the petrol and a fire broke out. Somehow I managed to escape. I still had inside the Shinel, the bullets for the gun. I had a burn on one arm and I went to the female doctor. [I said] - see here, I’ve got here some kind of a burn. I remember that she became angry with me. [She said] "Why did you wait for so long, what you’ve got here is a second degree burn."

She was a very nice doctor. She was a Russian married to an Uzbek. She helped us in every way. Hygienically, too. I wore my hair short. She told me: "Roza, you can let your hair grow, you are clean, no lice." This was an amazing achievement, because at the time we started to take care of ourselves, the conditions in the army were already much better.

I was assigned to the Polimyotni (machine gun) Battalion. It’s smaller than a cannon, I do not know how you call it in Hebrew. I was always in Communications. I was the operator. There were girls who worked with radio communications. After Oryol we reached a place whose name I do not remember, but there was some sort of a factory that manufactured goods for the army. We had it good there. A Russian woman was the manager of the factory and she treated us well. We guarded that factory. I worked as the operator in radio communications. Since these were field radio phones, and the cables had to be connected, we had to go out if there was a break or a discontinuity. We had to leave immediately, to find the discontinuity. From there we went on to Sarna. That was ‘44. The Germans retreated, and we were on their trail.

Going West was part of my plan and I meant to go through with it. We reached Sarna26, there were no Jews. Sarna was a whole town when we got there and one night swarms and swarms of planes came and destroyed it in one night. This was in the summer of ’44. The Army started using the Radar stations and demanded that some girls would be sent there to work. As it happened I had a commander who was a very intelligent man. He knew whom he was dealing with when they had to stand and dig the Zemlianka -the ditches. He used to tell me, "Roza take a gun and stand guard." Once he asked me: "Roza, will you teach your children how to work?" He saw that working is not my strong point. So I told him: "Yes comrade, I’ll teach them." By the way, Michael Shapira and I were both in the same division.

It was suggested that the commander should send me to the Radar division but he said: no. Instead when a request came for some girls for division headquarters, this commander said: "That’s a job for you." He sent me and two other girls. We were highly regarded. We did not go out to repair the lines. We were told: "Wait until the battalion people will fix it. You wait here." Then the commander asked for us back. But they did not let us go. We remained in that division. With that division we later passed through Ro27.

At that time I had already met [other] Jews. They were Partisans who returned from the forests. That was the end of ‘44. We arrived there in early winter. We spent quite a lot of time in Kovel. That was actually my last stop in the army. And we lived a good life. We lived in the city itself. When we were not on duty, we were free to go wherever we wanted. I was in that famous synagogue. The Jewish Partisans took me in. I spent a lot of time with them. They were residents of Kovel28. There was a Jewish doctor there, a Major. I was on guard duty. The commander called me and told me to escort the Major home, because he was short sighted. I led the Major. I also did not see very well, I did not have glasses, so I tell him: Comrade Major (in Polish)29 so he tells me: there’s a pit here. And we were inside the pit, and he was trying all that time to convince me: "Roza, we are Jews, we can take pride in the fact that we are Jewish. The Russians, they are no better than we are. We as Jews need to be proud to be Jews. We are doing our part in serving our homeland." He was a very nice man, he was an older man. If he was 40, I must have been 23, so he was older. The commanders there were also very nice. All in all, it was a very good time to be in the army.

All that time I worked in communications.. But we had fun, went to the movies, danced a lot. One good thing about the Army was that there was always an accordion at hand and everywhere, even on an empty stomach, we always danced, the others always sang,. I did not sing, because I do not have a voice. At that time our morale was always high. There were girls who always had a good time. There was one girl who intentionally became pregnant, because she wanted to go home. She wrote us a letter. She had had a daughter and she was happy. I’m telling you I was treated fairly. They knew that I did not belong to those who were prepared to have a ‘good time’. There were all sorts of crazy things happening. I can also tell you about what went on with the commanders. We were quite cheeky towards the commanders. We did not take them seriously. If I hear sometimes from someone who told me about being treated badly by the commanders, by the Soviets, I can’t complain. I was always treated well. At one place I had an Anti-Semitic [commander] and he gave me a headache. Starshina, that was his rank. He was a Sergeant Major. He gave me lots of headaches. But on the other hand, there was a commissar who was Jewish, and she intentionally confronted him in order to protect me. . .

Looking back on the experiences I have related, I came to the conclusion that the periods that I did skip over, as if they had not been important, those periods, were one of the most crucial in my life. It was a time that actually molded my personality. It was a time that made me act the way I acted. There were all sorts of changes in my character. I just did not put it together. It was a hard time, a dark period in life. If I go back quite a bit, it was the time I said it was not very important. It was a time that perhaps subconsciously, I wanted to forget, and is why I do not really remember. After thinking, and I thought a lot about it, I came to the conclusion that was really a hard and quite crucial time. It was a period of about a year- year and a half.

After I analysed this whole period, I understood there was much more to it. Initially I wanted to define it as a kind of mist that seems too difficult for me to get out of. Perhaps it would be hard to understand, but later as I lay in bed, suddenly it seemed to me, there was some kind of a long strip, rectangular, with a cover on top and it had cracks in it. I wanted to get out of it. Each time something else came up, a fragment, maybe a small part of a whole, and I just couldn’t get to wholeness. Maybe it is hard to understand it, but it was a very odd feeling. But on the other hand it had life lessons that I had learned . For many years I had it so hard, even in the Kibbutz. This oral history is before my time in the Kibbutz, but it made an impact for many years. I call it a "blacking out" of a very long period.

If I think about it, there are many things that I cannot connect. But at that time I learned what it meant to be a girl from a well to do family, a girl who never in her life learnt how to work, did not know how to work, whom the parents thought would always have a servant, thought would not have to do anything. For instance, I did not know how to wash the floors. And several times I was punished, because I refused to wash the floor. That could have been in ‘43-’44. All of it happened during my period in the Army.. I was sent to clean toilets. This was a kind of punishment, because there was no way that I knew how to wash the floor. After that [punishment], I was utterly exhausted.

Where we lived depended on where we were. Once it was under the ground in an underground structure, or if we were in a city, then we lived in the houses that remained. Suddenly, I visualize this as if it were a photo. I cannot connect it to anything. I can see a photo for instance of a beautiful garden in the U.S.S.R. In the army, in the middle of all the action, with the travelling, with the moving around with the army, I remember this place, a beautiful garden. We were invited to a party, with all the goodies. Something rises to the surface and ends with that. I can see myself in the summer, and suddenly I see myself in the winter. It is cold, it is in the evening, we are in a very warm house, getting ready to travel. Where, for what reason, to where - I cannot remember. Fragmented pieces, I do not know where. I remember myself in a vegetable garden. I went to do something in the vegetable garden, with nice people.

What I’m trying to explain here is that this is a period that I cannot put together. These are all tiny pieces of things. I remember myself in a Zemlianka, in the winter, it is very crowded, we are all on a bunk, sleeping. If one wants to turn around everyone had to wake up. There is no water, nothing to drink. So we melted snow. I do not remember when it was. There is more and more. These are things that I just cannot, as I have said, break open the cover of the case, let’s say. At that time there was a very hard thing for me. I had stopped reading. I could take a book, and sit for hours facing the same page. Before I could read a book and recite the whole book, from the beginning to the end. To read a book, even today, I have to page back, in order to remember what happened before.

This thing also disturbed my studies. I had it much harder during the studies, even in this country, because somehow the concentration, the memory, was damaged at that time. What is interesting, is the fact that in my dreams as an example, this period did not appear. One period that did appear, which is very odd, are the matriculation exams. I always had to sit the History exam. For some unknown reason, my running away from the Germans, my desertion from the army, these are things about which I dream very often. I told about a period in which we were in a certain place where I could not remember the name, where we guarded some kind of a factory. I remembered it was a factory in which they made gun powder30. I’m trying to remember that period, which was a very good and enjoyable period in my life. I tried to remember if it was before that crisis, or after that crisis. I cannot.

What I do remember, is that we travelled aboard freight trains, weeks upon weeks. In that factory, there was a lot of celluloid. And many girls picked that celluloid up. We travelled by train, there was no electricity. The way in which we lighted the place up in the evening, was to take a conserved food tin, put petrol into it, and a cotton thread, and light it. In the morning we woke up with ash covered noses. What I remember from the journey, is that it was a long journey and we had fun. We always disembarked at the stops, and danced .It was quite a good period. But one night the female guard fell asleep. And the Koptilka, the conserved food tin, fell over and fire broke out in our cabin. There was a lot of celluloid there. It could have been a horrifying disaster. Because that cabin was extremely hot. The train was moving. The soldiers from the front end started shouting to the commander: the girls are on fire! We were lucky that we reached a road block and the train had to stop. They got us off in our underwear , and then gave us Gatkes (long underwear) and if I remember correctly, we reached Oryol .

From Oryol I got to Kovel very quickly. But it did not happen like that really. In Oryol we stayed for a short time, and then we went to Briansk, where we spent almost an entire winter. This was in the end of ‘43, the beginning of ‘44 . I began to look for Jews. And in the same manner that in Oryol the Gentiles did not want to talk about it, in Briansk they slowly slowly revealed to me that the Germans eliminated the Jews. There were no Jews amongst the service women with me. I was on my own. There were Jews at a higher rank, the commander and the doctor that I mentioned.

We spent the winter in Kovel . It was a period in which I let my situation deteriorate. I did not take care of myself. I was dirty. In Briansk, I remember that one bright day I decided that that was it, I had to become human. I told earlier that I took the sugar ration we got, went to the market, sold it, bought perfume. As much as I was able to I mended the skirt, shortened it, and the shirt. That was the time that I decided I must live, be a human being. As far as appearance was concerned, I started to become human again, to keep clean, to get over the head lice, to live like a human being. We spent the winter there, probably the end of ‘43, ’44. Then from Briansk we continued due west and arrived at Rovno.

In Rovno we stayed for a very short period, a few days, I cannot remember exactly. I actually cannot remember anything about Rovno, and then we arrived at Sarna. And here, suddenly everything opened up. It is coming back to me now. We did not spend much time at Sarna, a few weeks. We were not in the town, we were in the fields and that was very lucky on our part. They had built these underground structures and we lived there and from there we saw how the Germans arrived one night, company following company, and finished off31 the city. When we came to Sarna, Sarna was a whole city. That night they finished it off. They tore down the entire city. We were lucky, they did not hurt us. The Germans would shoot off parachuted flares. When they would fall to the ground, the girls would run to collect the cloth.. It was a "Zaide (silk) Balloon". One of the girls ran to fetch the cloth and the cloth was still burning and it scorched her.

From Sarna we went to Kovel. It was in the summer of ‘44. And that was a time that I remember well. I spoke about a commander some time ago who asked me if I would teach my children how to work. He was a man who was older than me, a wise and very intelligent man. And he probably understood me much better than I understood myself, because I was quite stupid. He prevented me from doing two things which could have brought disaster upon me. The first thing was that I had read that someone wrote to Stalin that she wanted to go to a special unit. I also wrote to Stalin’s office, and told them that I know German and wanted to be a translator in the front. An answer came from Stalin’s office, saying that they would look into it. So this commander said: " Don’t be stupid. It’s not for you." He simply ignored the whole issue. Later I was told about the Lithuanian Brigade and I asked for a transfer into the Lithuanian Brigade. Then he told me again: "You’ll stay here, you’ll finish the war with us. There is nothing for you in the Brigade." And that was probably lucky for me as well, because there were very few survivors from the Lithuanian Brigade. With this commander I spent a lot of time.

Then we arrived at Kovel. It was not particularly devastated. But in Kovel I met for the first time with other Jews. That is, Jews who returned from the forests. The Partisans. They were black market merchants. I continued to work as a signals operator. We lived in a building in Kovel. These Partisans lived not far from us. I went there, even though they forbade us to have any contact with them. It was my first contact with Jews, with the Partisans. They were also the ones who influenced me later to escape from the army. But that was later, near the end. . They were the ones to convince me. They said: "Look, people are going to Poland. What are you doing in the Soviet Union? Go to Poland, and from there you can return to wherever you want, but what is there for you in the USSR?" I told them this: "I endured enough hardships from the Gentiles, what would I do in Poland? There’s nothing for me to do in Poland. I don’t know what’s happened to my family, and I have relatives in Leningrad. When the war is over, I’ll go to Leningrad, meet those people and stay there with them for a while." In the meantime, Lithuania was liberated..

For no particular reason, I decided to write to the postmaster in Kibart. Maybe he knew something about my family. I wrote to him, and I received a reply. He replied that he was not a local, and he had not heard anything about my family. He was not able to give me a reply and that’s that. I had nothing to look forward to. That strengthened my decision, that there is nothing left in Lithuania for me to return to. I have already got word from the Partisans and saw that there were no Jews. I had heard it all and I was so…I don’t know if you would call it hopeless, or maybe I just stopped feeling so much. Let me tell you, when I look back at that period, that was when I stopped crying. I forgot how to cry and since then I have never cried again.

I had to go on. It was a pleasant time in Kovel. We had fun, the clothes were nice, because a lot of material assistance came from the U.S.A., and there was also enough food. It was a good period. But when you think about it, sometimes there was something strange. I do not believe in dreams coming true, but I remember that one night I sat at the switchboard and I probably dozed off and within seconds of dozing off, I dreamt there was a lit candle and it slowly went out and suddenly it lit up again. The next day, I finished my guard duty and went to sleep. Then one of the girls said: "Roza you have mail." She brought me many, many letters.

I received mail from those people who were still in Kurgaly, and I received a letter from Israel. I had family there, and good friends, which I knew as far back as ’40. They made Aliyah through Japan. How I managed to get their address, I don’t know. They had sent me packages, and a letter. And suddenly I see five, six, seven letters from my father. I went into a state of hysteria, so much so that the girls had to slap33 me a few times, until I managed to read the letters . They were written in Russian, and he had been writing me for months. Since my military address changed time and again, the letters got held up while being rerouted, but eventually they arrived. . In one letter he wrote to me that he survived, but only him-- my sisters were lost. I ran to that Jewish family crying, because I said I had stopped crying, but then I cried. I was in a state of hysteria. They said: "What happened?" I said: "I got a letter from father." They said: "So why are you crying?" I said: "Yes, but my sisters were killed. Mom died before that." So they said: "Be happy, at least Dad survived." I could not handle it. Right then and there, I made a request to go on leave.

Father wrote from Kovno. After about a week went by, or even more, one of the girls came and said in Russian: "Roza, the commander asks for you". I said: "G-d, I didn’t do anything, why on earth is he calling me?" I ran to him. He said: "Sit down, tell me, what do you know about your family?" I told him: "Tavarish Mayor34, until about a week ago, I did not know anything. But a week ago I received letters from my father, saying that he survived and he’s in Kovno." He said: "Well, why aren’t you asking for leave? Why haven’t you submitted a report?" I said: "I did." He said: "Where is it?" Then I say: "In my commander’s pocket." "Okay," he says. "I received a letter from your father in which he says that he heard that you survived. I’ll make sure that you’ll get leave."

That very night, I remember as we sat and peeled potatoes, one of the girls came and said: "The Mayor asks for you." I came running. He said: "We approved your leave." And then the Sergeant Major tells me: "What’s with you, go back to the potatoes." I said: "Are you crazy? I got leave and I’m off, get my gear ready." Because they gave us some gear for the road. Soon I was on my way to Kovno from Kovel.

The drive took three days. If my memory of the road does not fail me, I went to Baranovich, through Baranovich I got to Lida, where we waited for a long time. I still remember. I sat and waited, A certain officer approached me, he tells me: "Miss, could you please guard my things?" I said: "I would be glad to Tavarish Lieutenant." He says: "I am not a Lieutenant." I said: " Sorry, Tavarish Mayor." Later the train came and they would not let me in. So the officer tells train person (in Russian): "Let my second pass." From there we arrived at Vilna. And Vilna was quite whole. In the train station there were Jews, young boys, and I was in uniform. They said: "Where are you going, who are you, from where did you come from?" This was in the end of December ‘44. They say: "Look, the train to Kovno has already left today. The train leaves only on every Monday. Come with us and stay with us and later, in two days time, you would go." So I told them: "No. I have only 10 days leave. Three days I have already wasted on the road. I have to get to Kovno." And truly, a freight train arrived, we boarded it, not just me. It was an open train, an open cabin, a platform,. All night we danced on the platform to keep warm. Early that morning I got to Kovno, not to the city itself, to Alexot. From that point I continued on foot. The train station was devastated. It is strange, because I had seen so many ruins, but when I saw the devastated train station in Kovno, it somehow hit home. I arrived there, found the street and the house, where father lived. Father was not home. At that time he lived with that woman who was in the photo with me, and a girl,. She was an orphan girl whom father kept at home.

Father was not there. They hid me to surprise him when he came back. They prepared him that indeed I arrived. I do not need to tell you about the meeting. It is hard to describe. How father got my address, how he actually found out that I was still alive, I have to go back a bit. In Bogoroslan, there was a relative-search office. One night I sat at the operator room and I remembered that family that we met when we traveled, when the war just broke out and I made a silly mistake by not crossing with them to the other train. I remembered that I saw them on the way.

I wrote to Bogoroslani, I asked for their address, and got it and wrote to them.. They were in Stalinova, that was quite far into Asia. This was the family of my two girl friends. Their brother was in Moscow. He took them to Moscow and they studied medicine there. They were in Vilna. If they are still alive, I do not know, but both of them became doctors. Twenty years ago and even more than that, when I studied at "Hasharon", a young nurse came from Vilna and she told me about them. So I tried to make contact with them. They wrote to me only once. They had gone on to Moscow. I still had a girl friend from home, who was a pianist. She was in the Lithuanian Brigade. She appeared in an entertainment group. In Moscow she happened to meet my friends, the two girls, and they gave her my address.