South Africa

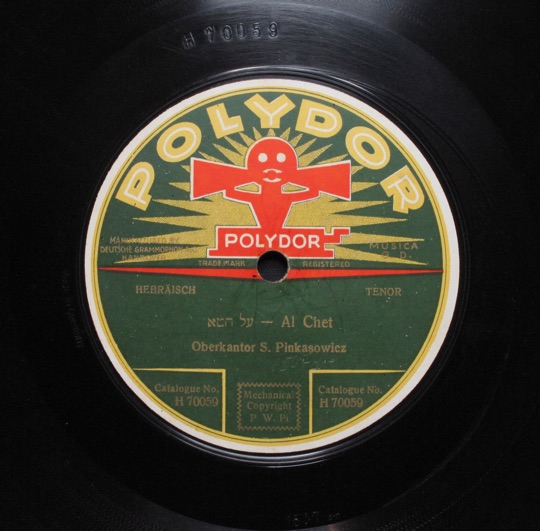

Al chet = Polydor H70058

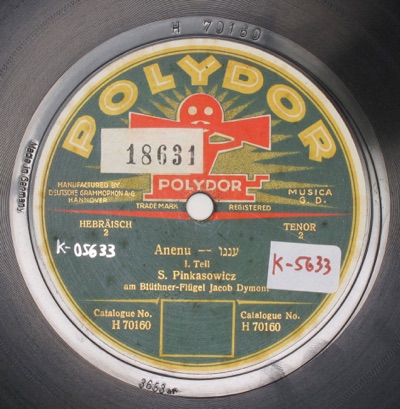

Aneinu = Polydor H70204 (year 1930)

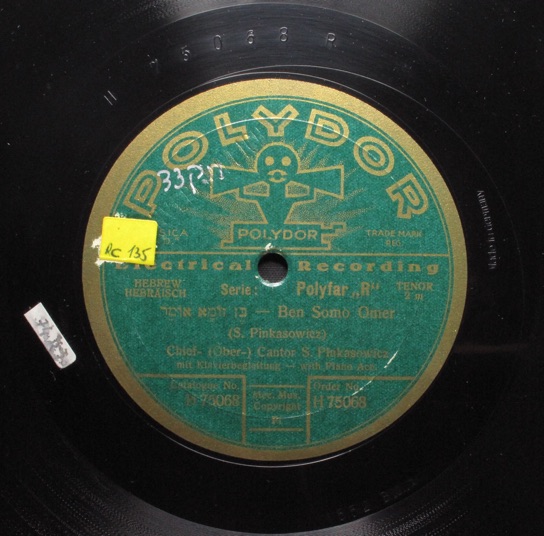

Ben zomo – Polydor H75068 (year 1932)

Retzei = gramophone H70014-5 (circa 1924)

Ein kitzvo = gramophone H70002 (circa 1922)

Geshem = gramophone H70044-5 (mid 1920s)

Haneiros = polydor H75018 (mid 1920s)

Information and letter from S. Leifer

Brooklyn N.Y.

My favourite cantor is long forgotten Shlome Pinkasovitch (Pincasovich, Pincasovicz, Pinkasovich).

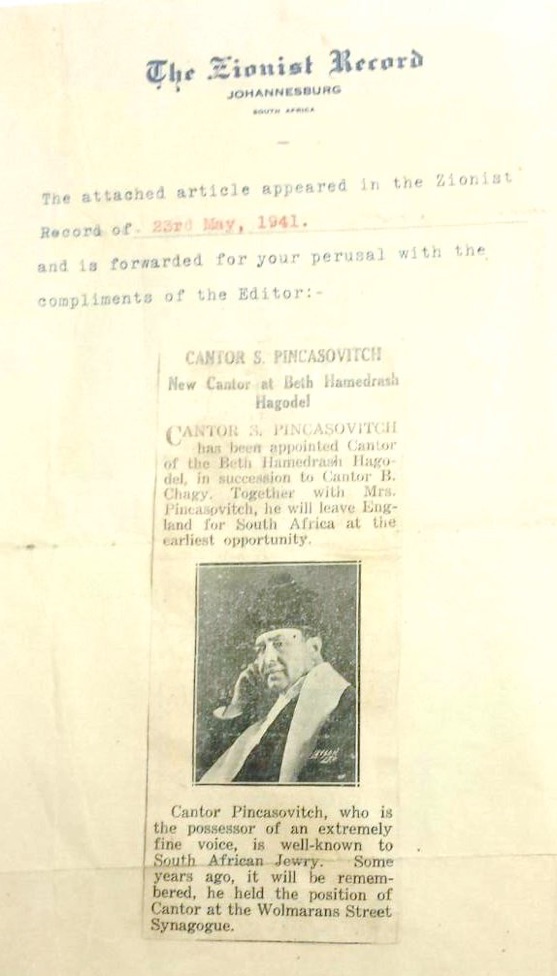

Shlome was the cantor at the WOLMARANS STREET SYNAGOGUE in 1930, returning in 1941 as cantor of the BETH HAMEDRASH HAGODEL, succeeding the famous Cantor Berele Chagy.

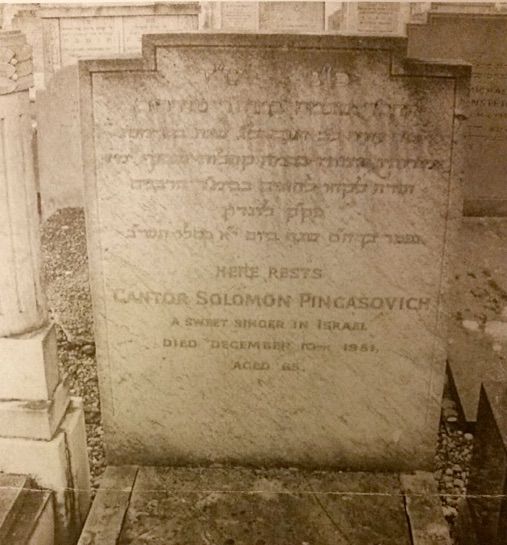

In 1946 he retired to London, England and served as a lecturer and Dean of the School of Music at Jews College, until his death on 10 December 1951 (י"א כסלו שנת תשי"ב)

He recorded more that 300 recordings between 1912-1933 on the Gramaphone, Polydor, Odeon and Homochord (Homokord) labels.

I have a large collection of his recordings, and I have his bio (he writes at length about his life in South Africa).

His name sadly vanished from the cantorial arena.

Lately, chazonim and balei tefila are becoming aware of his music and nusach, thanks to groups of chazonim and researchers, who have been spreading the word and sharing some recordings.

We plan on publishing a double cd of his recordings with a booklet containing a well documented bio based on his writings and newspapers cuttings etc.

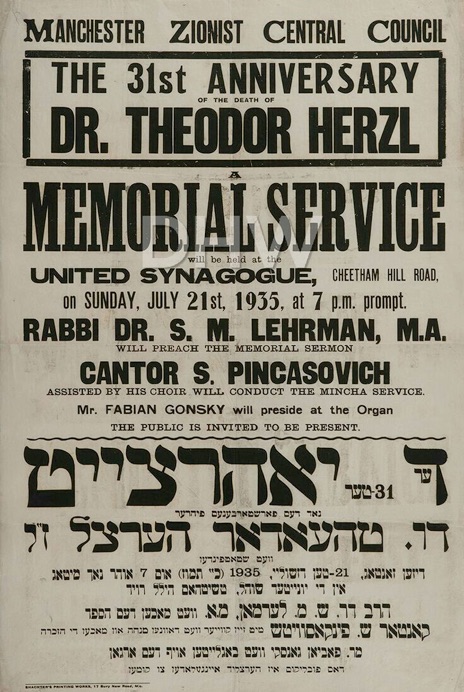

We have received considerable support from Manchester kehiloth (where he was the cantor in the late 1920s and 30s.

We are still looking for some documentation and photos from his time in Cape Town and Johannesburg.

I was delighted to see your website, that you are actually reviving the history, so I am reaching out to you for you help, if you have anything about him.

My friend, Geraldine Auerbach MBE, alerted me to Geoffrey Shisler's fabulous website:

http://geoffreyshisler.com/biographies-2/salomo-pinkasovitch/

Geoffrey Shisler is a most interesting man and a visit to his site is a must!

Follow his blog!

Like Pinkasovitch, Geoffrey also taught at Jews' College.

This is what he has on Pinkasovitch:

Haneiros - Maoz Tzur (w. choir)

Retzei Gramaphone H70014

Geshem both parts

Ochiloh Loeil

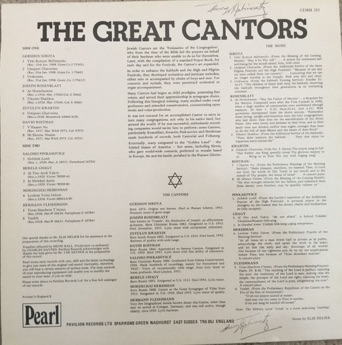

From the Cover: SALOMO PINKASOVICZ

Born Ukrainian Russia 1886. Graduated from the Odessa Conservatoire 1904. Made hundreds of recordings, mainly for Homokord and ‘DGG’. Voice of exceptionally wide range, from lyric tenor to basso profound. Died London, 1951.

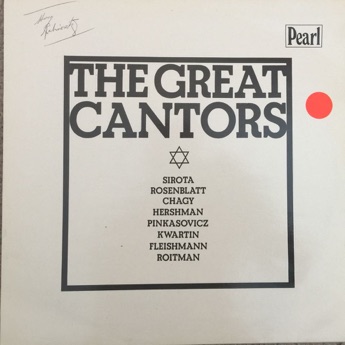

I found this LP amongst over 120 chazonis vinyls my dad, Cantor Harry Rabinowitz, left behind.

Shlome Pinkasovitch

SALOMO PINKASVITCH

My father was born in the small village of Dzigovka in the Podolian region of the Ukraine in 1886. His father was an itinerant Hebrew teacher and, though himself not a Chassid, claimed descent from Rabbi Pinchas of Koretz, a contemporary and disciple of the Bal Shem Tov, the founder of Chassidism. As a small boy my father saw a Hebrew document to prove this, known as a ‘Yichus-Brief’, but his mother, who didn't read, sold it together with a few valuable Hebrew books when her husband died of consumption at the age of 26. There were five children in the family and a sixth, a daughter, born posthumously. From earliest infancy my father loved nothing better than to sing and at his father's death left home to sing with a wandering cantor as a boy soloist. He had an unusually beautiful soprano voice and soon became known as the boy nightingale. The little money he earned he sent back to help his mother maintain the family and home. He learnt all the tradition and the correct ‘Nusach’ during his work as boy soloist, and one of the cantors with whom he sang taught him ‘the secrets of music’ as notation was called. He taught himself the principles of theory and harmony from booklets issued by a Cantor Birnbaum (a German Cantor) that appeared in Yiddish translations in Russia. Armed with this knowledge he sat an examination for admission to the Imperial Conservatoire of Odessa when he was fifteen, for his voice had broken thus depriving him of earning some money. So brilliantly did he pass the examination that he was awarded a scholarship and free tuition as well as books, music and the uniform of the Conservatoire (striped trousers, brass-buttoned jacket and cap ornamented with a rosette). As the ‘Numerus Clausus’ operated at all institutes of learning in Russia under Czarist rule, this was an immense achievement for a Jewish boy. My father studied composition under Professor Vinogradnikoff, who predicted a great career for him as a composer and admired above all his almost

Schubertian gift of melody. The young student won several prizes while at the Conservatoire. (I have one really beautiful song in my possession, a setting of a German poem by Uhland.) At 18 he graduated and was declared a ‘Free Artist’, the usual designation at Conservatoires of graduates ready to practise their art. My father hoped to study a further two or three years at St. Petersburg. His professor promised to help him obtain permission to reside there as Jews were not usually permitted to do so. But it was July, and good young tenors or basses were in demand for the coming New Year and Yom Kippur festivals. During his Conservatoire holidays my father had often sung at various Odessa synagogues, because while still a student his voice had returned and he had even had voice tuition at the Conservatoire. Now an agent secured him a good engagement at Akkerman, a small Black Sea port. He went to lodge with a relative, Rabbi Joseph Trostmann, Head of the local Yeshivah. There he fell in love with Eugenia, the youngest daughter of the house and, as the feeling was mutual, a whirlwind courtship was followed by marriage after only six weeks. Young Salomo changed his plans regarding his future; he could always become a composer later. He was going to Vienna, the Mecca of singers, to have his voice trained for opera. Together with his young wife he landed in Vienna early in 1904, aged about 19, his wife a year older. His teacher was Franz Haback, a great teacher and scholar, author of a book on the castrati. Salomo and his bride had very little money and lived in furnished rooms. They were educated people, reading Tolstoy and Goethe and going to the Opera if they were lucky enough to be offered tickets by a conductor. They read the Neue Freie Presse and later in Berlin, the Tageblatt. A child, a little boy, was born in 1905 and died at a few months, but Eugenia gave birth to a daughter, Anna, in 1906. There was no money left for further study. Salomo had studied the roles of the Duke in Rigoletto, and Don José in Carmen and two Wagnerian parts: Lohengrin and Tannhäuser. Prof. Haback who had known Wagner, told him that Wagner hated the so-called Wagner-bark and wished his singers to sing bel canto. Haback taught all his students in bel canto and in the open Italian style of singing. With him he studied a wide range of Lieder. Years later I used to accompany him in such things as Winterreise and Dichterliebe. He greatly loved Hugo Wolf of whose Mörike Lieder he must have given first performances in a number of Hungarian towns.

All the agents to whom he applied were delighted with his voice, but thought his repertoire unsuitable, especially the Wagnerian parts that required tall, heroic men; he was short and then very slender. They thought he would look insignificant on stage. And so Pinkasovitch turned aside from dreams of opera and rapid fame and accepted a small post at a small synagogue in the working-class district, the Twentieth District of Vienna, the Brigittenau. The need for daily bread was more important than fame, especially since Eugenia’s widowed sister and their father, the rabbi, had arrived in Vienna, hoping to find a home with the young singer. The custom of caring for family was very strong, and the young couple would not have dreamt of turning their own kin away. The widowed aunt Pessy stayed with us for good, the rabbi died in Vienna after some years, though he had to die in hospital, needing an operation. Young Pinkasovitch had now fully determined to become a

great cantor if he could not be a great opera singer. But no great post turned up in Vienna so in 1911 he accepted the well paid post as cantor of a small town in Galicia, a Polish-speaking part of the Habsburg Empire. The financial position improved at a stroke, as did, too, the reputation of the young cantor. In 1913 he was called to Czernowitz in the Bukovina region of Austria, a German-speaking, modern, town of some 100,000 inhabitants. There a life-contract as Oberkantor was offered him. This meant security for good, and security in old age was a highly desirable thing at that time. The ‘Temple’ as it was called, was a magnificent building, its golden cupola could be seen from every hill surrounding the town. (Incidentally it is mentioned in a book by the modern writer Gregor von Rezzori, who calls the town ‘Czernopo’.) The young cantor was idolised by the entire population. Singers from the opera (the town had a permanent opera) came to hear Pinkasovitch sing at the Sabbath service.

In April or May 1914 my father was invited to make some dozen or so recordings. He was delighted and chose some of the members of the choir to sing with him. What the recording company was called I do not now exactly recall but quite certainly the picture of the HMV dog was on the records. The recording took place in a room of the Schwarzer Adler, the town’s leading hotel. I, the eldest daughter, was present. I was very young at the time, but as a budding pianist was interested in all things musical. (Later I was a pupil of Frieda Kwast-Hodapp at the Berlin Stern Conservatoire.) Father sang into a horn and the choir had to be grouped very carefully about him. Some of these were ‘Monarch’ records, bigger than the others. We did not receive a single copy of any of them for at the end of July war broke out in Austria. Around 1922 we did hear them at various private houses in Berlin. Papa was fascinated how his voice, on these early recordings still quite a lyric voice, had in between become a Heldentenor. I don't think any of these records now remain, but as I say, I remember so clearly the engineer positioning my father before the horn with much care. And then there was much ‘messing about’ to get the choir right.

The pleasant life in Czernowitz came to an abrupt end with the Declaration of War. My father had remained a Russian subject, he never paid much attention to political situations. And so, early in August 1914 there was a knock at our door at dawn and there stood two men to escort Pinkasovitch to the Town Hall and thence to the Railway to be interned for the duration at the village of St. Martin near Braunau (the birthplace of Hitler, but then he was only Corporal Hitler). Pinkasovitch, who was fastidious in his habits, had to sleep on the floor where rats and mice ran about freely, wear prison garments, and eat vile food. His family knew nothing of his whereabouts as the Russians had taken Czernowitz and most Jewish inhabitants including the entire synagogal council had fled. Eugenia sold the few things of value she had acquired, silver spoons and forks, quilts, clothes, anything that would bring in something to feed the family that by now consisted of three little girls and a newly born son. Then, miraculously, we had a telegram from the head of the house. The Governor of Upper Austria had made a tour of the prison and internment camps to see if all were being decently and humanely treated. No one dared say ‘No’ except Pinkasovitch who boldly stepped forward and told the

Governor that as a singer his voice was suffering from breathing in coal dust as his special task was to empty coal-trucks. The governor was a typical old world Austrian aristocrat and great music lover. He at once ordered this particular internee to come to his palace in Linz and sing for him, an order which the internee gladly obeyed. The result was immediate freedom and permission to go and live in Vienna for the duration. Our joy was not diminished by having to leave our beautiful home in Czernowitz and go and live as refugees in yes, the 20th District of Vienna. The Austrian Army had meanwhile retaken Czernowitz and Pinkasovitch was asked by his synagogue council to return and resume his duties. He did so and took his family with him, but the episode lasted only some three months, for then the very able Russian General Brussilov began his 1916 Offensive and retook Czernowitz. Pinkasovitch and his family became refugees again; there was no Governor to help against the Russian Army. We were taken to Prague, but allowed to find private lodgings. After some weeks my father saw in a Jewish newspaper that the Hungarian town of Gyöngyös or, rather, its Jewish inhabitants, required a cantor. My father applied, went to sing a trial service and was engaged at once. He knew that the life contract with his Czernowitz Temple was null and void. Many people felt sure that the Central Powers would lose the war and no one could know what would happen to Czernowitz. (It is now Cernauti, a Rumanian town, in fact.) We arrived in Gyöngyös, a sleepy one-horse town in the summer of 1916 and in 1917 the entire town was burnt to the ground, not by enemy action, but by lack of water. But a cantor was required in the much bigger city of Miscolc, not far from Budapest, and as usual, after one trial service, Pinkasovitch was offered the post, which he held till 1920. He would have stayed longer, he was idolised as in Czernowitz and felt happy there, but after the disaster of the collapse of the Hapsburg Empire a fascist régime under Admiral Horthy gained control. The things that later became the order of the day under Hitler now became known in Hungary, though probably not outside. The régime was violently anti-semitic, Jews disappeared or were murdered or tortured in cellars, beaten up, excluded from schools, their livelihoods taken away. There was a vacancy in Berlin at the Adass Isroel Synagogue and as always, when my father applied he was at once offered the post.

And so in 1920 we moved to Berlin. We lived in Artillerie Strasse, not far from Alexander-Platz, now famous for the film of the book. He made his best-known records at this time. First for the now defunct Homocord company, then for the Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft for whom he sang some 300 pieces. He was also highly talented as a composer, but he wrote only for the synagogue. It is a pity he wrote no Lieder or secular choral pieces. He composed with great ease. He could compose in a corner of the kitchen whilst my mother occupied herself with cooking and we children ran around. The results of his considerable talent are lost for he was by nature naive and unworldly. He never had a reliable friend to advise him.

In Vienna Pinkasovitch had become acquainted with Leo Fall and we saw his Rose von Stambul in Miscolc. We found it melodious and charming. My father also knew Jadlowker personally in Vienna, though at the time my father was still a

student of singing and Jadlowker a star of the Hofoper. I myself heard him at the Berlin Staatsoper as Faust. He was by then around fortyish or more, but still slim, tall and elegant and his voice very beautiful. I also heard him in Handel's Judas Maccabeus at the Oranienburgerstrasse Synagogue, a modern Liberal synagogue, that sometimes put on oratorios on Sunday evenings. Professor Einstein was in the orchestra; he was a passionate lover of the violin, though very likely no great player. He and Schnabel played duo-sonatas together, as was well known. I had the honour of shaking hands with Prof. Einstein at a Jewish charity concert where my father sang some Jewish folksongs, and I played a little Rondo by Beethoven that I had recently played at a pupils’ concert in the Beethoven Saal. He was kind enough to invite both my father and myself to his house to repeat the performance, but Papa was socially a shy man who did not like to be a sort of Exhibit No.1 at famous peoples’ houses, and so found an excuse for refusing politely. And I followed suit, naturally.

Manfred Lewandowski was a frequent visitor to our house and I think he told us he was related to the great Jewish choirmaster Lewandowski, whose settings of the liturgy were sung in most German synagogues just as Sulzer’s were in Austria. His famous ancestor was choirmaster at the most orthodox synagogue in Germany, the Alte Synagoge, where my father was the cantor. Mildly ironic that Manfred was at the Friedenstempel. I heard him sing some operatic arias at our house, at a musical evening. We now and then indulged in that sort of thing. I loathed them, as I always had to play, both as soloist and accompanist, but Philip Newman often played for our guests and was greatly admired for his unaccompanied Bach.

Conditions in Germany began to deteriorate, fascism began to grow and the monetary system to lose its value. In 1921 Pinkasovitch went on tour to England to sing in London and Manchester and was offered the post of cantor of the New Synagogue in Manchester. He accepted and so, once again, the family made a fresh start in a new country.

On the last day of the year, Samuel Langford wrote in the Manchester Guardian, “We have never in our own experience heard any man singer attempt such an exhaustive vocal feat as that attempted by the Cantor last night. He is a massive and robust figure, not in appearance above forty years and in robustness his voice would fully equal that of Mr. Frank Mullings. The name of ‘The Jewish Caruso’ is not so extravagantly bestowed on him, for he has command of a splendidly open Italian method and the range of his voice is equally extraordinary with its bulk. His art of bravura ornamentation is in some degree artificial, for it passes the limitations of what may be called legitimate vocalism both in range and in execution. He covered very little short of four octaves in his singing last night, from the high C to well on the way to the low C below the bass stave. The service singing does not allow him to spare the voice in any way . . . . we dare not describe the pianissimo of the upper octave as a falsetto tone, but its fineness and apparently endless range might well tempt us to that description, were it not for its beauty.

We have given enough details to convince all who believe our description that he is a quite extraordinary singer. He is also an abnormally beautiful singer, and he has considerably enlarged our ideas of what the voice of a man can do . . . The

ornamentation included almost every known ornament in music. The mordant is the most frequent of all, and is used from the most delicate pianissimo to the most brilliant vigour. It is executed at times with a strangely graceful pathos and at others with the most rude and brave audacity."

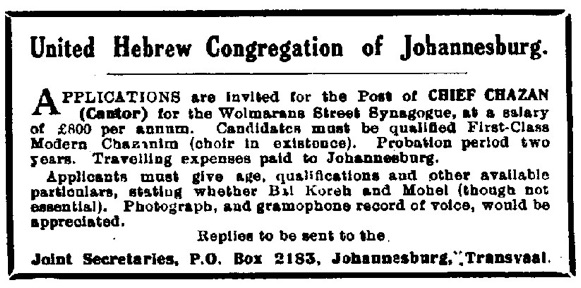

An emissary from the Great Synagogue of Wolmarans Street, one of the finest in South Africa (Johannesburg) arrived in search of a suitable cantor, heard my father take a Sabbath service and at once offered him a life-contract, with the at that time fabulous salary of £1,200 p.a. My father hesitated; we were happy in Manchester but the climate was miserable, so the idea of a sunny country was tempting. And so in 1925 he sailed for South Africa, the family following some weeks later.

The sun shone, the money was good, there was security and the people were friendly, but to my father South Africa seemed dull and boring and he often had heated I arguments with his synagogue council. He decided to resign his post and return to the Europe that he missed so greatly. He obtained the post of Cantor of the famous Alte Synagoge in Berlin in 1928. He had just returned from a highly successful tour of the USA, where he very nearly accepted a post in Philadelphia. Much misery would have been spared him had he accepted, but he loved Europe and he loved Berlin. The Alte Synagoge was more tempting than Philadelphia.

An article appeared in the Vossische Zeitung by the novelist and musicologist Dr. Walter von Hollander lamenting that ‘we have now, alas, only a few truly natural singers’. Amongst than he named Caruso, now dead, Gigli, Maria Ivogün and also ‘the Jewish Cantor Pinkasovitch’.

Our return to Berlin coincided with the great period of the Kroll Opera, which we often visited. It was only some five minutes or so away from our home in Reichstagsufer. We heard Freischütz there, though most often Klemperer directed modern works; the Kroll was famous at the time for staging modern opera. Lotte Lenya as Seeräuber-Jenny was superb. We were all there at the second performance. A friend of Weill who was also a friend of my father gave us eight complimentaries for the second row of the stalls so we saw perfectly the original cast. We were all captivated by Weill’s music and Brecht’s text. It was a great success. The Theatre at Schiffbauerdamm was very near - we just had to cross a bridge to reach it.

After the burning of the Reichstag, (our beautiful home was just a street away), the councillors of the synagogue urged him to leave as the position for Jews was made daily more and more unbearable. He agreed that this was the wisest thing to do. The decision was less difficult for whilst in South Africa he had taken out naturalisation papers and so was now a British Dominion subject and had no need to stand outside foreign consulates, as other unhappy Jews did, to beg for admittance. He took up the post of cantor to the United Synagogue in 1933 but went back to South Africa at the outbreak of war in 1939, not to his previous synagogue, but to a rather smaller one. In 1946 he came back to England and founded the cantorial school at Jews’ College in London, a post he held till his death in December 1951.

© 1988 Anna Eker - daughter of Pinkasovitch

Al Cheit

Aleinu

Ben Zoma

Advertisement from the Wolmarans Street Shul in Johannesburg in March 1923, before Cantor Shlomo Pinkasovitch accepted the post for much more money with a life contract

S Leifer

26 April 2017

One correction I think I never wrote to you is: Cantor Pinkasovitch came to the Wolmarans street shul the Great Synagogue in year 1925 untill 1928

He returned in end of 1939 untill 1946 to another temple (I posted a newspaper that he took the post of cantor berele chagy when he left s.a.

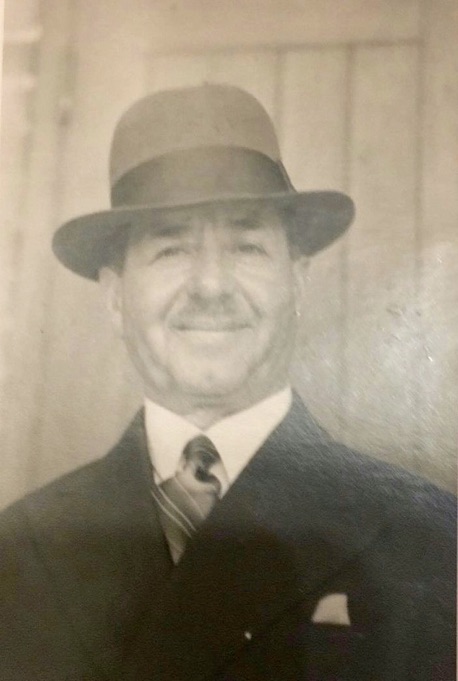

Here I attach a newly found very nice photo of cantor pinkasovitch. Also one nice poster of him doing a Mincha with his choir, and his Matzeiva in London (Bushey lane cemetery)

You may add it to the site.

Kol tuv

S. Leifer