NAME:

Joseph L. FRIEDLÄNDER

Hebrew: Yosef

Parent of: Henriette (Jette) FRIEDLÄNDER Munk

Child of: Aharon Jehuda and

Born: 1767 in Mühlendorf [or Millendorf], Hungary (then Szárazvám, Sopron County, 47° 50' N., 16° 26' E.), now Müllendorf, Burgenland, Austria.

Died: Bautzen, 9 July 1841 = Friday, 20 Tamuz 5601

Married: before 1795 to Gittel Rinkel or Ringel (Ringlin) of Schlichtingsheim, Posen, in Schlichtingsheim

Saxon Residence Permitted: 1813, 1816, 1820, 1839

Profession: Translator from Russian and dealer in second-hand clothes; 1819—salesman

Cause of death: unspecified

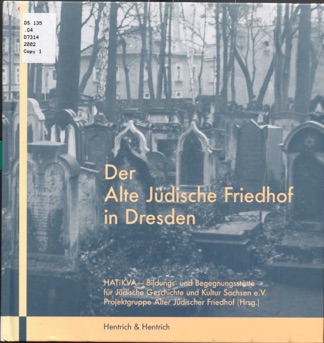

Buried at: Old Jewish Cemetery, Pulsnitzerstraße 10, Dresden, Saxony [Germany], 12 July 1841 = Monday, 23 Tamuz 5601, Grave 18/16.*

See Staats-filialarchiv Bautzen (Germany), Folder 50347-237 for probate estate.

Miscellaneous: Joseph claimed that his father was a wholesale dealer in Preßburg, now Bratislava, Slovakia, and a protected Jew. At age 13, he began to learn the profession of salesman, and as a young man, he traveled extensively with his father. At age 20 Joseph met Samuel of Vilna in Vienna and worked as a clerk and secretary for him for eight years, learning Russian. He then worked for the dealer Markus Prager in Frankfurt an der Oder for two years while Joseph’s wife, the daughter of Joseph Rinkel or Ringel of Schlichtingsheim, worked in Prager’s kitchen. They lived with his father-in-law, Joseph Ringel, in Schlichtingsheim where he was a protected Jew, for 16 years, where he had his own trade and traveled to Saxony. He was in Dresden on 12 March 1813 and was kidnapped by Russian troops in Weißenberg, but, when they discovered that he could speak Russian, they instead hired him as a translator. He arrived ill in Bautzen and became a translator there, being paid one Thaler per day, a large salary. During the May 1813 Battle of Bautzen against Napoleon, Friedländer claimed, he kept the Russian troops from plundering the small villages and returned what the Russians took. He claimed that he prevented the Russians from destroying several bridges over the Spree River. After the battle, he returned to his father-in-law’s house in Schlichtingsheim and then returned to Bautzen as a translator for the Russian troops. Later, his wife joined him in Bautzen from Schlichtingsheim. The city fathers granted him the personal right to sell second-hand clothes, but if he died, his wife would have to leave Bautzen. He was 48 years old on or before 18 August 1815. The king of Saxony granted him permission to stay in a rescript dated 10 September 1815. In 1816 he is known to have had good German skills and sold second-hand clothes. In 1819 Friedländer obtained two passports (two trips), issued in Bautzen.

As a result of professional jealousy, the intrigues of the Salesmens’ Guild, and the hostility of the local authorities, he had many difficulties. A 25 November 1818 report of the Administration of the Margraviate of Saxony shows that it intended to expel him, and the Privy Council ordered his expulsion on 1 November 1819. In contrast, the Master of the Handicraft Guild supported him. On 22 November 1819 Friedländer renewed his application. His physician stated that he suffered from hardening of the liver, shortness of breath, stomach cramps, and indigestion. His wife suffered from nervous excitement as a result of pregnancy. Thus, a trip was dangerous. On 15 March 1820 the King allowed him to stay in Bautzen.

Per Dresden State Archives Document no. 2361, Residence of the Jews in Bautzen, 1819: The Jewish tradesman, Joseph Friedländer from Schlichtingsheim, in 1818 petitioned the King to extend permission for him to reside in Bautzen. A report of the Privy Council of 7 December 1819 relates that Friedländer came to Bautzen in March 1813 and in the year 1819 had already left his birthplace Mühlendorf in Hungary 46 years earlier. Concerning his family, it further relates that his “child is weak and not more than 2½ years old,” and his wife is pregnant. The Bautzen city administration found a place for the Jewish family to reside because it had work for Friedländer in translation service for 1813-1816.

In 1820 at Heringsgaße 6, Bautzen, in a house owned by Johann Gottlieb Drahm, shoemaker, Friedländer lived in a small garret with a sick wife and an unstated number of children. If his wife dies, he must go to Schlichtingsheim with the children because business was bad, but Schlichtingsheim did not want him because he had no employment there. He was forbidden to remarry in Bautzen if his wife died. In 1830 Friedländer, dealer in second-hand clothes, lived at Hohengaße 13, in a house owned by Johann Gotthelf Friedrich, shoemaker.

Per Dresden State Archives, MdI No. 916 (The recognized Jews permitted residence in Saxony outside Dresden and Leipzig), pp. 2-3: Report of the district administration of Budessin to the Ministry of the Interior (28 November 1839): “The only Israelite living here, Joseph Friedländer, in consideration of his actions, namely in the war year of 1813, as Russian translator of the said city, performed services, as related, for the magistrate and a part of the citizenry resulting in sovereign permission to maintain residence here under an order of 11 September 1815 for a period of two years, and then under an order of 5 June 1820 ‘so long as his future conduct does not give rise to complaints.’” In 1837 he and his family received civil rights. Anna Flaschner, a distant relative born in Böhmisch-Leipa, was allowed to care for him starting before 1839 for about half a year. He proposed to hire the Jewish servant girl, Maria Fischer, from Böhmisch-Leipa. He is widowed, over 70 years old, with one daughter married and living in Poland.

In 1835 Friedländer was the only Jew who lived in Bautzen along with his family. His 17 year-old daughter attended the Protestant school and had good grades. Her parents taught her lessons in religion and Hebrew reading and writing. About 1838/39 she married and went to Poland. At about this time Joseph Friedländer’s wife died. In 1839 Friedländer at age 70 was the only Jew in Bautzen. In the Summer of 1840 he sought to renew the permission with Marie Fischer from Böhmisch Leipa as servant to nurse him. He received that permission for one year.

Resided at:

1767 Millendorf or Mühlendorf [Szárazvám], Hungary, now Müllendorf, Burgenland, Austria.

Friedländer said that it was near Preßburg [now Bratislava, Slovakia]

1787-1795 Vienna, Austria, at the house of Samuel of Vilna

1795-1797 Frankfurt an der Oder, at the house of Markus Prager

(no Prager or Friedländer listed in available Frankfurt/Oder city archival Jewish records)

1797-1813 Schlichtingsheim, Posen, probably at the house of Joseph Rinkel or Ringel

1813 March in Dresden, then in Weißenberg

1813-1841 Bautzen, Saxony, (Germany), in 1820 at Heringgaße 6, in 1830 at Hohengaße 13

Sources:

Files of the Oberamt of Bautzen, now in the Bautzen office of the Staatsarchiv Dresden:

Book Chapter Date

1. 553 107 18 August 1815

2. 554 11 12 January 1816

3. 562 46 24 March 1820

NAME:

Gittel RINKEL Friedländer

Parent of: Henriette (Jette) FRIEDLÄNDER Munk

Child of: Joseph RINKEL and

Born: 1768 (?) in Pavlov (Neudorf), Bohemia, Austria, now in Pelhřmov District, Czech Republic, 49° 23' 58" North, 15° 14' 53" East

Died: 16 October 1839 = Wednesday, 8 Marheshvan 5600 in Bautzen, Oberlausitz (Upper Lusatia), Kingdom of Saxony (Germany).

Married: before 1795 to Joseph Friedländer of Bautzen, Oberlausitz (Upper Lusatia), Kingdom of Saxony, (Germany), in Schlichtingsheim [Szlichtyngowa, Poland]

Saxon Residence Permitted: 1820 (through her husband)

Profession: Housewife

Cause of death:

Buried at: Old Jewish Cemetery, Pulsnitzerstraße 10, Dresden, Saxony [Germany], 18 October 1839 = Friday, 10 Marcheshvan 5600, Grave 17/13*

Miscellaneous:

Resided at:

1768 Pavlov (Neudorf), Bohemia, Austria, now in the Czech Republic

-1795 Schlichtyngowa, Poznań, Poland/Schlichtingsheim, Posen, Prussia, (Germany)

1795-1797 Frankfurt an der Oder, at the house of Markus Prager

(no Prager or Friedländer listed in available Frankfurt/Oder city archival Jewish records)

1797-1813 Schlichtingsheim, Posen, probably at the house of Joseph Rinkel or Ringel, her father

1813-1839 Bautzen, Saxony, (Germany), in 1820 at Heringgaße 6, in 1830 at Hohengaße 13

*See HATiKVA - Bildungs- und Begegnungsstätte für jüdische Geschichte und Kultur Sachsen e. V., Projektgruppe Alter Jüdischer Friedhof, ed., Der alte jüdische Friedhof in Dresden: —daß wir uns unterwinden, um eine Grabe-Stätte fußfälligst anzuflehen, Teetz: Hentrich & Hentrich, 2002, 301 pp., including bibliographical references. At Library of Congress, and at Leo Baeck Institute, New York City, DS135.G4 D7314 2002; and at New York Public Library, *PXS 02-4745.

Resources specifically relevant to Joseph and Henriette Friedländer:

“Finding My Ancestor’s Place of Burial,” Avotaynu: The International Review of Jewish Genealogy, Bergenfield, NJ: Avotaynu, Inc., Volume XVI, Number 4, Winter 2000, p. 89. See http://www.avotaynu.com/journal.htm or search http://www.worldcat.org

“Gives Advice: Revisit Your Old Research,” Avotaynu: The International Review of Jewish Genealogy, Bergenfield, NJ: Avotaynu, Inc., Vol. XXI, No. 1, Spring 2005, p. 62. See http://www.avotaynu.com/journal.htm or search http://www.worldcat.org

The book can be found in the research library nearest you by using www.worldcat.org, a service free to researchers.

Many thanks to

Edward David Luft

Juris Doctor

https://sites.google.com/site/edwarddavidluftbibliography/

who submitted this information and documents

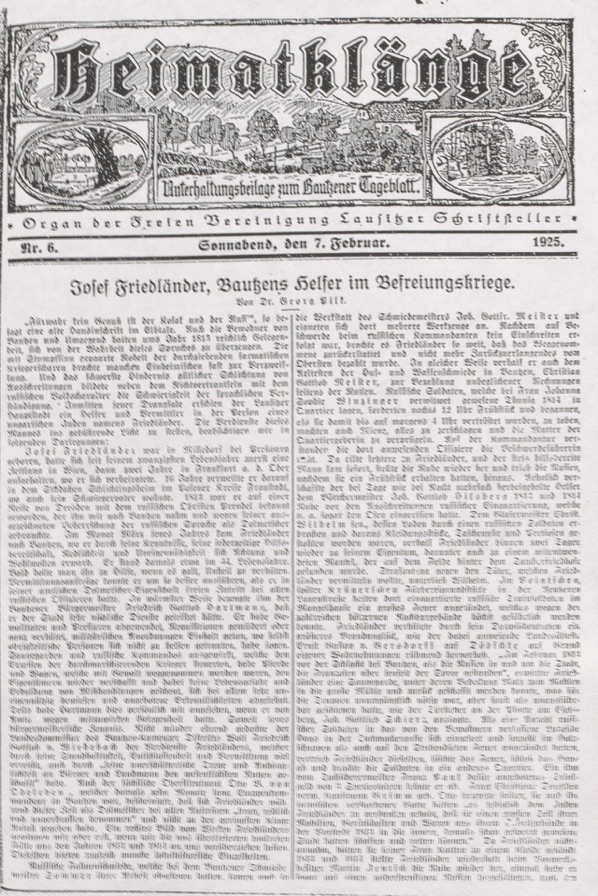

Heimatklänge

Entertainment supplement of the Bautzen daily newspaper. “Organ of the Free Association of Lusatian writers”

No. 6 Saturday, 7th of February 1925.

“Joseph Friedländer, Bautzen’s helper in the fight for freedom.” By Dr. Georg Bilt.

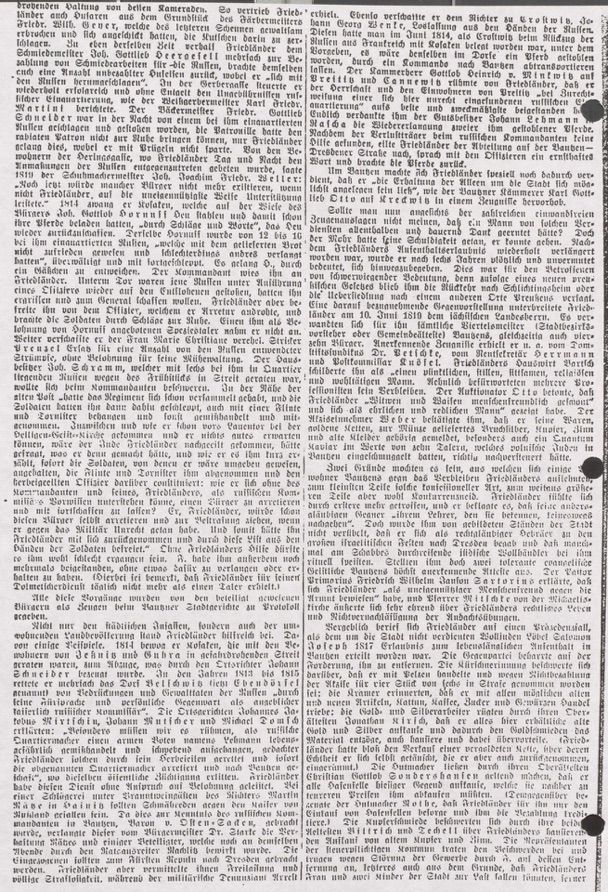

“Surely there is no pleasure in meeting Cossacks and Russians” [which rhymes in German] says an old inscription on a house in Elbtal {community}). Around the year 1813 the inhabitants of Bautzen and environs had plenty of opportunities to convince themselves of the truth of this saying. The coarseness of the warrior hordes that marched through, combined with their brutality, brought many inhabitants almost to despair. And the hardest obstacle that prevented an amicable settlement of riots was - next to the unfamiliarity with the Russian national character - the difficulty of language communication. In the midst of those trials and tribulations a helper and mediator appeared in the Lusatian capital, a Hungarian Jew named Friedländer. In the following statements we would like to give the due credit to him.

Joseph Friedländer was born in Milledorf, near Preßburg. When he was twenty years old, he moved to Vienna and lived there for a while; then he spent two years in Frankfurt (Oder), where he married. For the next 16 years he lived in a town called Schlichtingsheim in Fraustadt County of Posen Province, where his father-in-law also lived. In 1813 when he was traveling from Dresden, he became acquainted with Russian colonel Prendel, who took him to Bautzen, where he needed an interpreter. Friedländer had an excellent command of the Russian language. In March of that year Friedländer came to Bautzen, where he was respected and liked because of his knowledge, his willingness to help at any time, his honesty and unselfishness. He was then about 44 years old. He was asked for help very often when it was necessary to prevent harm. He was able to fulfil mediation tasks in the best way due to the fact that as an official interpreter, he had free access to all Russian officers. The mayor of Bautzen, Friedrich Gottlob Hartmann, expressed in the warmest way that he had done very useful services to the city. He prevented violence and pressure, mitigated or completely prevented requisitions, stopped military orders in cases when even the highest officials did not have enough courage to help. He influenced security and the Russian commandos, { caused} [who] {the} excesses of soldiers {that} [who] were marching through, he recovered horses and carriages, which were taken away by force and returned them back to the owners, and he did not hesitate to risk his life or endure maltreatment; he always showed his unselfish attitude and rejected all tokens of appreciation. Hartmann could sometimes observe his conciliatory actions, when he had the opportunity to participate in them ex officio. That was the mayor’s statement. The country’s commissioner of Bautzen-Mamenz district, Wolf Friedrich Gottlob von Wiedebach, also honored Friedländer’s services, who in his opinion achieved a lot, thanks to his steadfastness, determination, and mediation, and who thanks to “his unwavering loyalty and devotion to citizens and compatriots, obtained the most significant benefits.” Even the Saxon Lieutenant Colonel Otto B. von Odeleben, who was then departmental commander in Bautzen for the period of ten months, certified that during this time in the case of all orders Friedländer has proved to be a “good, honest, and undaunted” interpreter, and he never gave cause for the slightest complaint. But we can only get the right picture of Friedländer’s work if we consider actual events, handed down to us from the years 1813 and 1814. At the same time they also offer us some additional historical details.

Russian blacksmiths, who had to perform their work at master blacksmith Sommer in Bautzen, also came to the workshop of master blacksmith John Gottfr. Meister, and they expropriated several tools there. Although no intervention was made after the complaint reached the Russian commander, Friedländer managed to retrieve all the expropriated tools, and if this was impossible, the equivalent in money was paid by the colonel. In the same way, he also helped the eldest of the hoof and gunsmith in Bautzen, Christian Gottlob Meister, to make the Russians settle their unpaid bills. Russian soldiers who in 1814 billeted with Johanna Sophie Winzinger, the widow Thunig, demanded breakfast at midnight and when they were made to wait for it until 4 o’clock in the morning, they started to go wild and even threatened to smash everything and to beat the mother of the woman who billeted them. The officers who were present at headquarters did not acknowledge the complaint that she made. Then she rushed to Friedländer, and this man, helpful as always, came immediately, restored law and order and drove the Russians away, after they received their breakfast at the house. Similarly, the helper summoned several times during the days and at nights in 1813 and 1814 to master cooper Joh. Gottlob Hilsberg where he provided peace and prevented riots by Russian soldiers who were billeted there and who, among other things, even managed to demolish the oven. Friedländer also helped master glazier Christ. Wilhelmsen when a Russian soldier broke in to his shop and stole some clothes, a pocket watch and jewelry, but within two days all possessions were returned to the owner, including a coat, also stolen, and which was found in the field behind the Taucherfriedhof [cemetery]. Wilhelm refrained from starting criminal proceedings against the perpetrator, whose name Friedländer wanted to pass to him. In Voigt’s and later Krüger’s dye-works in Lauenstraße locations exercising Russian soldiers who were billeted there set a huge fire in a delapidated house, which could have been extremely dangerous because of the numerous wooden buildings located in the neighborhood. Friedländer, by his intervention, prevented a major fire catastrophe, as he was praised by the commissioner of estates of the realm, Ernst Gustav von Gersdorff of Töbschte, who happened to see the fire himself. “In February 1813 before the Battle of Bautzen, when the Russians stayed in and around the city, but the French were on the other side of Spree River,” Friedländer obtained a protective escort, which made it possible to transport malt for grinding in the large mill and then return. That was absolutely necessary for the troops but seemed impossible, as the guard at the gate to Eselsberg, John Gottlieb Schierz, claimed. When a larger number of Russians came inside the abandoned house belonging to Lutzsche in Tuchmachergasse, and set afire, both a wooden shed and the floorboards in the rooms, they were driven away by Friedländer, who put out the fire, closed the house, and took the soldiers to other billets. He refused to accept any money that master cloth cutter Franz Paul offered him for this, being of the value of 3 Speziestalern. Christiane Dorothea, née Otto, shopkeeper Grimm’s widow, confirmed later that for her and her already deceased husband “it was only thanks to the Jew Friedländer that they managed to take and rescue a large amount of movables, devices and goods from their factory building in the suburbs in 1813 and bring them inside of the city that was already locked by then.” Since Friedländer did not accept any remuneration, in 1813 they sent his wife a caftan for a dress and in 1814 Friedländer once again restored peace at the property of distillery owner Martin Jentsch; once he even smashed one of those stubborn Russians, despite the threatening attitude of his comrades. Friedländer also drove away hussars from the property of dye-works master Fried. Wilh. Geyer, they having violently broken into his barns and being about to crush the chutes in there. At the very same time Friedländer several times helped master blacksmith Joh. Gottlieb Heergesell to obtain payment for ironwork made for the Russians and brought him back a large number of unpaid-for horseshoes, for which he had to “keep battling with the Russians.” In the Gerberngasse he frequently resolved and without any payment, the problems that arose regarding the billets for the Russians, as reported by master tanner Karl Friedr. Martini. The master baker Fried. Gottlieb Schneider was hit and pushed at night by a Russian who was billeted at his house, the patrol was not able to make the aggressive man calm down; only Friedländer managed to do this, and he did not spare him his punches. One of the inhabitants of Heringsgasse, where Friedländer days and nights was asked to fight Russian riots, master shoemaker John Joachim Friedr. Weller said in 1819: “Many citizens would not live here any longer if it were not for Friedländer’s support that he provided in the most unselfish way.” In 1814 “with punches and words” he forced the Cossacks, who stole hay from the meadow of the citizen Joh. Gottlob Hornuff and already loaded it on their horses, to return the hay back to the owner. The same Hornuff was overpowered and dragged away by 12 to 16 Russians who were billeted by him and that were dissatisfied with bread they were given and insistently demanded different bread.” But H. managed to escape through a small street. The commander told him to go to Friedländer. At a gate the escapee came across the same Russians, together with an officer who seized him and wanted to take him to the general. But Friedländer freed him from the officer, whom he threatened with arrest, and with his punches made the soldiers calm down. Friedländer did not accept a Speziestaler offered him as a reward by Hormuff. Furthermore, he helped Marie Christiane, married to Stricker Preuzel, and a judgment was rendered for a number of stockings stolen by the Russians, without any reward for the efforts he made. The homeowner Joh. Schramm, who had come to an argument with six Russians who were billeted at his house, because of a breakfast, wanted to complain about it to the commander. The regiment was already gathered close to the old post office, and the soldiers dragged him away; they also draped a gun and a knapsack on him and maltreated him in various ways and took him away. Meanwhile, as he had already reached the Lauentor gate at the Holy Spirit Church and could not expect anything good to happen, Friedländer hurried after him and asked what he had done wrong and, as he told him, he immediately stopped the soldiers who had surrounded him, and took the gun and knapsack from him. Then he asked if they have the right to arrest and take away a citizen and also Friedländer, who is subject to the Russian commissioner. He, Friedländer himself will arrest this citizen and bring him to punishment if he had done something against the military. That way Friedländer took him back, and thanks to this ruse he managed to free him from the hands of the soldiers.” Without Friedländer’s help, this situation would probably have come to a worse end. Moreover, F. later helped him much more often, without demanding or receiving anything for this help. (It should be noted that for his service as an interpreter Friedländer did not receive more than a thaler per day.)

All these situations were reported for the record at the Bautzen city court by citizens who witnessed them in person.

Friedländer proved to be very helpful, not only to the inhabitants of the city but also to the rural population who were living in its surroundings. A few examples will follow. In 1814 he convinced the Cossacks who fell into an argument that threatened to become dangerous, with the inhabitants of Jeßnitz and Guhra, and made them withdrawn themselves, as testified to the local judge Johann Schneider. In the years 1813-1815 he several times saved the village of Belschwitz (now called Ebendürsel) from oppressions and violence by the Russians “through his intercession and personal presence as the alleged imperial Russian commissar.” The local court officials, Johannes Jakobus Mirtschin, Johann Mutscher, and Michael Domsch, declared: “We especially need to mention the situation when Russian billeting officers mishandled a poor messenger named Lehmann and then left him wounded, Friedländer hurried immediately and managed to save him, and he also arrested the above-mentioned billeting officers and took them to Bautzen, where they were condemned to public punishment. Friedländer fulfilled this service without claiming any reward. During this fight at the tavern owned by judge Martin Raße in Hainitz, one could also hear vilifying words against the Russian emperor. This information was brought to the Russian commanding officer in Bautzen, Baron von Osten-Sacken, who demanded that Mayor Dr. Starke arrest Rätzes and some other participants, which was carried out in the evening by the knight, Rachlitz. They were brought to Dresden to Prince Repuin. But Friedländer managed to negotiate their release and complete impunity, while the military informer was arrested instead. He also helped the judge in Crostwitz, Johann Georg Wenke, be released from the hands of the Russians. In June 1814, when Crostwitz was occupied by Cossacks during the retreat of the Russians who were returning from France, he was taken to Bautzen under the pretext that a horse was stolen from them in the village. The chamberlain, Gottlob Heinrich von Minkwitz in Breititz and Cannewitz, praised Friedländer that he supported the authorities and inhabitants of Breititz “to rebuke the Russians who billeted there without any permission”. Finally, the landowner Johann Lehmann in Rascha owed him for having received back his two stolen horses. After the one that he suffered the loss but found no help from the Russian commander, Friedländer followed the troops on the road from Bautzen to Dresden, talked to the officers in serious words and brought the horses back.

In Bautzen and its surroundings Friedländer’s merits were especially important, due to the fact that he was “very careful about the preservation of the roads around the city,” as was pointed out by the Bautzen chamberlain, Karl Gottlieb Otto in Kreckwitz.

Given the numerous and impeccable testimonies of the witnesses, is it not obvious that a man of such merits deserved sustained appreciation everywhere? But the servant has fulfilled his duties, so he could go. After Friedländer’s residence permission was extended several times, after six years unexpectedly and suddenly he was importuned to move away. This turned out to be a difficult situation for him because, according to a new Prussian law, he was not allowed to go back to Schlichtingsheim or to move to any other town in Prussia. Based upon this fact, on the 10th of June 1819 Friedländer submitted an appeal to the territorial overlord, the king. All representatives of the citizens (city district representative or community representatives) in Bautzen, and at the same time fourteen citizens, interceded on his behalf. He received certificates of appreciation from, among others, the cathedral’s representative Dr. Betschke, from Treasurer Herrmann, and from Postal Commissioner Kuösel. Friedländer’s landlord Bartsch described him as “a punctual, quiet, well-mannered, religious, and charitable man”. Similarly, the representatives of several other professions demanded that he be allowed to stay in the city. Auctioneer Otto stressed that Friedländer “protected widows and orphans in a very friendly way” and that he “proved to be an upright and honest man”. The tax collector Weber confirmed that he duly reported all his goods, gold chains, damaged silver wares that he delivered to the mint, copper, tin and old clothes, especially a quantum of caviar that was ten thaler worth and that was smuggled to Bautzen by Polish Jews; everything was subject to subsequent taxation as it should be.

There might have been two reasons why some residents of Bautzen did not want to keep Friedländer in the city, and these were only in the slightest degree denominational reasons; it was mostly due to the jealousy of his competitors. Friedländer felt more hurt by this first reason, and he complained that his opponents of a different faith “do not follow at all their teacher, whom they profess to follow.” But educated classes of citizens did not take it amiss that he, as an orthodox Hebrew, went to Dresden to participate in the major Israelite celebrations and that sometimes Jewish wool merchants who traveled through the city on Sabbath dined ritually with him. Moreover, two tolerant Lutheran clergymen from Bautzen provided him with highly appreciative certificates. Pastor-in-Charge Frederick William Janson Sartorius said that Friedländer “proved to be an unselfish philanthropist fighting poverty” and Pastor Mitschke of St. Michael’s Church expressed his great reverence for Friedländer’s lawful life and the fact that he did not neglect his prayers.

Friedländer in vain cited a precedent, when a Jewish wool merchant Salomon Joseph, who did not perform any services for the city, in 1817, was granted permission to remain in Bautzen for life. The opposing parties insisted on forcing him to leave the city. The furriers’ guild complained that he traded in furs and had been punished for failure to pay the excise duty imposed on four out of six pieces; and the shopkeepers recalled that he traded in all kinds of products, old and new, including calico, coffee, sugar and spices; gold and silver workers complained through their main representative, Jonathan Kirsch, that he bought all the old gold and silver that was available here, and thus deprived the goldsmiths of the material; he even peddled and thereby overcharged people. Friedländer admitted merely that he sold a gold chain but he himself was deceived about its authenticity, and he also accepted it back when returned. The hatters claimed through their main representative, Christian Gottlob Sondershausen, that he bought all rabbit furs in the region and that they had to buy them from him at much higher prices. (In contrast, the hatter Rothe testified that Friedländer bought rabbit furs for him only and that he credited his payments). The coppersmiths complained through their two main representatives, Bittrich and Techell, about Friedländer’s peddling purchase of old copper and tin. The representatives of the tax authority shared these complaints, and due to the dislocation in trade, demanded that F. be expelled from the city, this last thing also by reason that Friedländer’s wife and two children could become a burden upon the city; furthermore because he attracted foreign Jews and his apartment seemed to serve as a hostel for them; finally because he helped Polish Jews to escape, although they were arrested due to fraud (however, there was no evidence to prove this).

The behavior of the council in Bautzen was very objective and proper. Despite the old propaganda against Friedländer, the council requested for the higher administration office to prolong his permission to remain. The latter higher authority, however, stood on the side of the complainants. The numerous positive testimonies that Friedländer received seemed in their opinion “not to be given out of pure motives,” and they were not at all related to “the facts that were imputed to him and partly admitted, partly not rejected by him. Even if he was completely innocent, there was no reason to tolerate him further.” Who did not recall, when reading this last sentence, the words of our great Lusatian compatriot Lessing: “It does not matter, the Jew will be burned, anyway”.

But it was different this time. The decision of the Saxon king on the 27th of May 1820 stated that “Friedländer shall be granted the right to stay in Bautzen as long as his future behavior does not provide any reason to justify complaints.”.

(Source: Main State Archive Dresden, Germany, File 2361 “The sojourn of Jews in Bautzen” 1819.) --Translated by Małgorzata Grzenda, 2014

Joseph L. FRIEDLÄNDER

--Probate estate record translated by Roger Lustig, Princeton, New Jersey

Compiled by Eli Rabinowitz

Posted November 2013

Updated April 2016

Copyright © 2014-6 Eli Rabinowitz