Bielsk Podlaski

The Synagogues of Bielsk Podlaski

by Andrew Blumberg

Reviewing

and editing the translations of each chapter of the Bielsk

Podlaski yizkor book

(its full title is Bielsk-Podliask; Book in the Holy

Memory of the Bielsk Podliask Jews Whose Lives Were Taken

During the Holocaust Between 1939 and 1944), I’ve been

learning a lot about the town of my great grandfather Barnet

(Boruch) Blumberg and his brother Max (Mendel). Both were

active in the Bielsker

Bruderlicher Unterstitzungs Verein.

Reviewing

and editing the translations of each chapter of the Bielsk

Podlaski yizkor book

(its full title is Bielsk-Podliask; Book in the Holy

Memory of the Bielsk Podliask Jews Whose Lives Were Taken

During the Holocaust Between 1939 and 1944), I’ve been

learning a lot about the town of my great grandfather Barnet

(Boruch) Blumberg and his brother Max (Mendel). Both were

active in the Bielsker

Bruderlicher Unterstitzungs Verein.

Because

nearly

every chapter of the book was written by a different author,

the collective work contains related stories and perspectives

spread across multiple chapters.

My objective here is to combine some of the descriptions and photographs in the yizkor book with documents, photos, and hand drawn maps contributed to the Bielsk KehilaLinks site, and an architectural plan obtained from the Polish archives, to provide an overview of the three main synagogues in Bielsk.

In his introduction to the book, Editor Haim Rabin wrote:

“What is amazing is that numerous synagogues and Torah study halls existed in Bielsk, reflecting various differences in style of worship, socio-economic classes, and the like, and yet they all seemed to accept the leadership of one Rabbi!”

This broad religious environment was described by Zvi Kadlabowski in Community Life in Bielsk:

“There was a group of Chasidim in Bielsk, but a small group. Aside from the five known beis-medreshes [lit. house of learning], the big ones, we had minyans. The minyans were on the periphery, far from the city center where the big beis-medreshes were located. There were Jews who wanted to pray quickly but in the large, old beis-medreshes prayers lasted a long time, but in the minyans it was one-two-and-done. There were five or six minyans. Permanent minyans were held in homes. One of them was called “the electric minyan,” because electricity operates quickly and the praying there went so quickly. Another place was called “Rosenberg's minyan” after the owner of the apartment where the minyan was located.”

In the chapter The Game of Shadows and Lights in Bielsk, Yakov Shemesh described the atmosphere of Shabbat and the High Holy Days:

“How nice it was to observe how the Jews received the Shabbat in Bielsk. Everyone gathered in Beit HaMidrash in their best clothes, and all the worries of the weekdays seemed to have disappeared from their faces. In Bielsk they really felt the holy Sabbath in their hands.

The worshipers literally fought with each other to receive a guest, or guests for the Sabbath, and no one missed this opportunity - of the mitzvah of “hospitality.”

When the holidays, and the Days of Awe [High Holidays], were approaching, everyone prepared with reverence to stand before the judgment of the Creator of the world, and surpassed themselves on Yom Kippur. The prayer houses were illuminated with an abundance of lights that had a kind of holiday and remembrance, and the shamásh, R' Baruch, lit the large candles in the afternoon before Kol Nidre, and placed them inside special sandboxes. The city's Jews received the holy day with trembling, awe and fear. No one dared to desecrate the holy day, even indirectly, and on the eve of Kol Nidre prayer, everyone reconciled, forgave each other's transgressions and turned from enemies - to friends.”

While there were many choices for prayer, it is the three synagogues located in the center of town that are written about in detail. They are Ichel’s Bet Midrash and the Shaarei Tzion and Yefeh 'Einayim synagogues, all named for important people in the town’s history.

In a few cases different names were used by authors to refer to the synagogues. Alternative names include Der Alter (The Old), the Alt-Niya (Old-New), the New Bet Midrash, and the Hachnasaat Orchim (Hospitality) Bet Midrash. Ichel’s Bet Midrash is clearly identified as the Old Bet Midrash. It isn’t clear how the other names match up to Shaarei Tzion and Yefeh 'Einayim.

If you have ever been involved with a synagogue, especially as a board or committee member, you are likely familiar with the disagreements that can arise. And in that case, you will relate to some of the anecdotes below. They should not be taken as the defining character of Bielsk. To the contrary, the authors of the yizkor book tell us that the defining character of the town is that Bielskers maintained “a deep sense of communal responsibility.” In a section of his introduction, titled Image of a Society which is elaborated on by other authors, editor Haim Rabin provides this summary:

“That which makes Bielsk unique, and reflects itself in the memoirs of those who survived, is the deep social instinct that guided and moved its people toward the creation of a community based upon mutual assistance. Both young and old were endowed with a deep sense of communal responsibility, which was to become the legacy of all of Bielsk's Jews. Though of limited means, the people of Bielsk did not want to see among them brothers who must beg for their meager existence, lowering themselves in order to survive. They realized that the wanderer's staff and pauper's bag were too often the mark of the Jewish people, who lacked a normal and secure economic base. They knew that no segment of the Jewish people was safe from this, for it came to be a recurring condition throughout the dispersion. It was therefore incumbent upon those who could to extend a helping hand and in a manner that would help the recipient preserve his self-respect.

Throughout

the

years of its existence, the Jewish community of Bielsk

maintained a variety of charitable institutions, serving the

needy in the most dignified manner. There was little notice

given to those whose contributions

made these institutions possible, just as the people

served by them were never made to feel inferior because they

required assistance.”

Bielskers who came to the United States carried this ethic with them, as shown, for example, in the name, mission, and deed of the landsmanshaft they called the Bielsker Bruderlicher Unterstitzungs Verein – the Bielsker Brotherly Assistance Society.

The locations of the three synagogues can be seen on these maps:

- Hand drawn watercolor map by Libe and Bashe Kleszczelski

- Hand drawn map by Libby Utzyski Elson

- Map of the area of the ghetto, from a memorial plaque placed on the historical location of the Shaarei Tzion synagogue

Ichel’s Bet Midrash

According to

author Gedalia

Shtaynberg,

the early head of his family, Ich'leh (also Ichel and Itzele,

Hebrew איצ'לס), born in the city of Kamenets-Litovsk, was

after many years the first person to receive a permit to

settle permanently in Bielsk with a minyan of Jews. Motl

Levkovski

described Ichel’s Bet Midrash as having a “broad roof and

skinny walls… the Aron Kodesh

[the Holy Ark]… had wonderful carvings of hands raised toward

Heaven in eternal prayer. Here we children, after accompanying

our fathers to shul, played outside.” B. Carmon wrote in Centers

of Interest in Bielsk that it was below ground level in

a cellar “in the tradition of Karaites… so you had to go down

some stairs to order to enter.”

“It was a small synagogue that had an unusually exquisite Holy Ark. I have visited many synagogues and have seen many holy arks, but I have never seen an aron kodesh [holy ark] as lovely as the one in “Ichel's Beit Midrash.” What was so especially beautiful was the unique way that all the musical instruments, known from Jewish tradition to have been in the Temple [in Jerusalem], were carved into a first-class work of art. Neither in the diaspora nor in Israel have I seen such beauty and splendor as this. If my memory is not deceiving me, these adornments were done in pure silver.

The synagogue was mainly a place of prayers for artisans. In any event the more distinguished people would not go to pray there. There was no class warfare, no differences of yicchus [lineage], and everyone had a good feeling. Also, its outward appearance and limited area were evidence of that.”

Yakov Shemesh

paints an evening scene in The

Game of Shadows and Lights in Bielsk:

“... in the evening after the businesses and various concerns ended, the ancient and beautiful Yefeh 'Einayim synagogue, and the midrash houses of “Itzele” and Shaare Zion, were filled with ordinary people of all kinds who came to participate in a Mishnayot lesson, or to listen to a biblical chapter in Shulchan Aruch. Radiant was the appearance of Rabbi Reb Ben Zion [Sternfeld] zt”l,1 and his awe-inspiring figure and sincere humility attracted the common people from the leather worker to the carter, and they came, for half an hour, to hear the traditional melody of those studying Mishnayot or the Gemara. I don't remember the names of the explainers, but it is hard to forget the interest of the common people to each explanation, and every word, that came out of the mouths of the preachers.”

The following

chapters speak of Ichel and the synagogue named for him:

- Centers of Interest in Bielsk

- Bielsk Podlaski – My Birthplace

- The Game of Shadows and Lights in Bielsk

- Write a Book/Remember

- Synagogues, Sextons, and Trustees

- To the Memory of Bielsk and my Six Girlfriends

According

to Pinkas

Hakehillot Polin,

the Shaarei Tzion (Gates of Zion) Synagogue was built in 1889.

It was named after the

1903 book of the same

name

(containing legal rulings and answers to questions posed by

the Jewish community) written by Rabbi Ben Zion Sternfeld

(1835 – 1917), who was appointed Rabbi of Bielsk

after the death of Rabbi Yellin in 1886.

Gedalia Shtaynberg described fires after WWI as having destroyed “the three synagogues that were concentrated on one square,” which includes Shaarei Tzion. In Centers of Interest in Bielsk, in a section titled “The Controversy Over Hatikvah,” author B. Carmon tells a story that may explain the motivation that led to its rebuilding:

“Another contest in the [Yefeh 'Einayim] synagogue involved completely different characters. This struggle was over the singing of Hatikvah at the completion of services. One Jew, Kaplanski, was a hide trader by profession and a Zionist by outlook. A tough Jew with a strong, deep voice, he expressed his Zionism in fighting for the singing of Hatikvah after prayers on Simchat Torah. The devout religious and even more so the haredim, who were not Zionists, were of course against this idea. They said that this was a Chillul Hashem [a desecration of God's name]. And the fight was harsh. In most cases, Kaplanski won the argument. When the fight would not end, he would stop and then open up with his strong bass voice and belt out Hatikvah. He swept away his following of a substantial part of the worshippers and that ended the differences of opinion. That was the Yafeh 'Einayim Synagogue.

After that, in the early 1930s or at the end of the 1920s, the “ba'ala batim” [members with voting rights and eligibility for executive office] and the wealthy people started building a third synagogue called Shaarei Tzion [Gates of Zion]. It was a lovely, modern synagogue, and it stood on a tel on the road called Beit Midrash Street. There had been a synagogue building there at one time, but it burned down during World War I.”

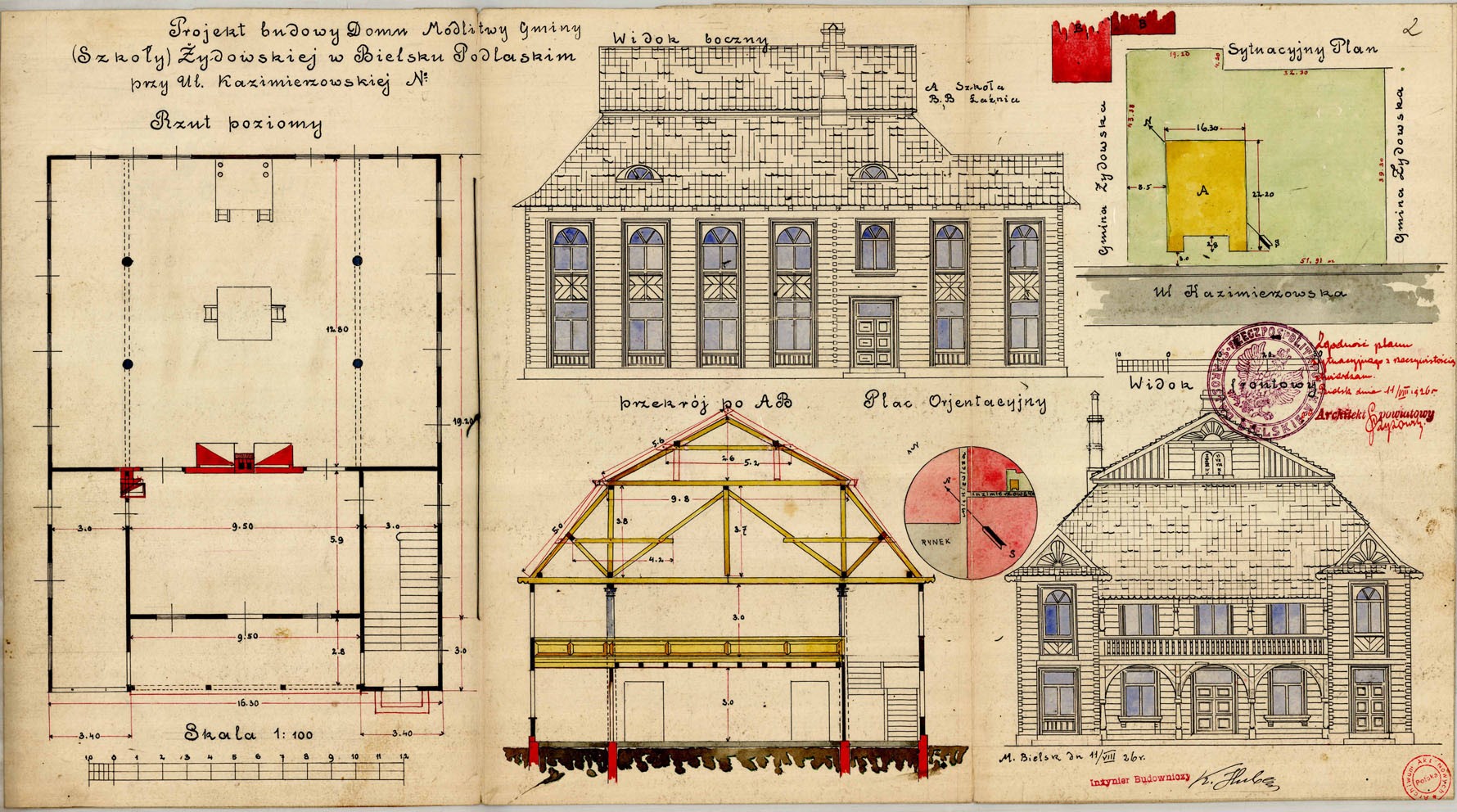

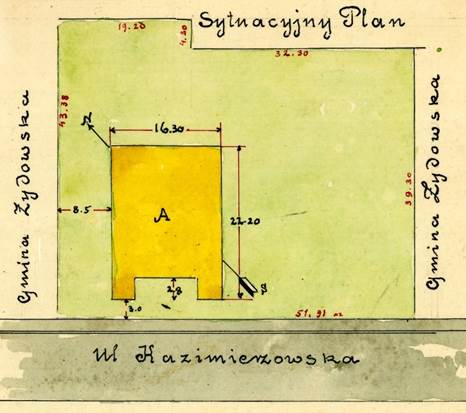

The two maps below are from an architectural plan for a synagogue in Bielsk dated August 11, 1926. They show that the synagogue would be located on Kazimierzowka Street near the intersection of Mickiewieza close to the Yefeh 'Einayim Synagogue. This is the location of the Shaarei Tzion Synagogue as shown on the map of the area of the ghetto.

The

complete

architectural plan also has front and side view illustrations,

diagrams of the interior, and measurements for

construction.Click the image for a larger view.

Source: National Archives, Archive of New Records, Warsaw, Poland - www.aan.gov.pl. Reference no. I 2386.

In a paper titled “Strictly Polish: Synagogues of the Early Twentieth Century,” author Eleonora Bergman wrote about Polish synagogue architecture “in the spirit and style of the dworek or small manor house,” popular “from around 1910 to the early 1930s.” During the interwar period, “designs for synagogues and other Jewish communal buildings were prepared by government architects.” About the Shaarei Tzion synagogue, she wrote:

“A 1927 [actually 1926] design for a synagogue in Bielsk Podlaski (a small town around 45 kilometers south of Bialystok) was certainly one of the most elaborate cases of the inclusion and creative compilation of many details taken from old synagogues in the region, with elements of folk art. This was one of those rare cases where the new synagogue was to be built of wood. It certainly helped to introduce the most traditional elements: the “broken” two-tiered roof (in this case, the mansard-type roof, more characteristic of the eighteenth century), probably covered with shingles. The entrance porch and the gallery above it could well have been used for dwelling houses or taverns, but we also know that similar ones were used in the eighteenth-century synagogues of the region. The side pavilions were most characteristic for the Grodno-Bialystok group of old wooden synagogues. We note that the interior did not reflect the symmetry of the exterior, which was rarely the case in traditional structures. We do not know if the new Bielsk Podlaski synagogue was ever built.”2

Thanks

to the Bielsk yizkor book and maps that were hand drawn by

Bielskers, we know that the Shaarei Tzion synagogue was

rebuilt around the time that the architectural plan was

created. As Gedalia Shtaynberg wrote, "It was a lovely,

modern synagogue." Whether it was built as specified in the

plan isn't known. At least not yet.

The Yefeh 'Einayim (Beautiful Eyes) Synagogue was referred to as the Great Synagogue – Bet Midrash Hagadol. According to Pinkas Hakehillot Polin its construction began in 1898 on the location of an earlier synagogue from the 16th century. It was named after the work of Rabbi Aryeh Loeb Yellin (1820 – 1886), whose commentary and comparison of the Gemara contained in the Babylonian and Jerusalem versions of the Talmud was so profound that it warranted to be published in the Vilna Babylonian Talmud (the Vilna Shas) published by Romm Publishing House in Vilnius, Lithuania. Its 1886 Vilna Talmud still serves as a definitive edition. Moshe Alpert provides this explanation in The Rabbis’ Deeds – The Beautiful Eyes:

“His commentary, which is a multi-dimensional book, is called “Yefeh 'Einayim” [lit. Beautiful Eyes] because it beautifies the eyes of man and it illuminates pathways for people in the sea of the Talmud. But there was someone who said that the man stood out for his beauty and was known for his beautiful eyes, so he called his book by the name Beautiful Eyes to teach you that the beauty of the eyes is measured by the quality of their vision and the essence of their perception. Thus he merited to be named after his composition, and no one remembered his real name and would only refer to him by the name “The Yefeh 'Einayim.””

The chapter Bielsk – As I Saw It From My Grandfather's House, describes the Yefeh 'Einayim Synagogue as:

“Not just the center of prayer; it was also a meeting place for the study of Torah. During the day there were a few people studying Torah, but in the time between mincha [afternoon prayers] and ma'ariv [evening prayers], they would come in from all ranks of society – artisans, shopkeepers and simple Jews and everyone studied. Each one sat according to his level of knowledge, in the group of Menorat HaMaor, Ein Yaakov, Mishnayot, up to Chevrat Shas.”

The groups were named after Jewish texts: Menorat HaMaor, “The Menorah of Light,” is a collection of midrashic sermons; Ein Yaakov, meaning Spring of Jacob, is a compendium of rabbinic texts; Mishnayot, a collection of the Jewish oral traditions; Chevrat Shas is a reference to the Mishnah, the first major written collection of the Jewish oral traditions that are known as the Oral Torah.

The text from Centers of Interest in Bielsk included in the section above about Shaarei Tzion, continues with an account of the struggles among the range of Jews who attended Yefeh 'Einayim:“This

was where the rabbi of the city, Rabbi Bendas,3 prayed. It was

where the wealthy merchants, who

would

only go

to pray on

Rosh

Hashanah

and

Yom Kippur, would purchase their “seats” for the High

Holidays. Here there was ongoing

“class warfare,” especially on Yom Kippur – and almost every

Yom Kippur. On that day there is, as you know, a very

important “Maftir”

reading called “Maftir Jonah” and whoever “purchases” Maftir

Jonah is himself very important

and highly honored. The money collected for this acquisition

is then used for various things in the synagogue

but also for other matters such as Keren Kayemet [JNF], Linat

Hazedek [a charitable organization for the ill described in

more detail in the chapter] and more. The well-to-do of the

town would always sit by the eastern wall

which is closer to the rabbi. These were the wealthy

merchants, landlords, and people like themselves. In the last

row of benches sat those rich enough but not elite enough –

butchers, tailors and the like. And the battle was waged

between the last row and the eastern wall as to who would

deliver “Maftir Jonah.” From the eastern wall someone would

proclaim his price for the maftir. Immediately the opposition

answered from the butchers. For the most part, it would be the

butcher, the successful butcher, whose shop was on Beit

Midrash Street. When the golden prize would be declared at the

eastern wall, he would raise it by half a gold coin. And at

once they would jump up from the eastern wall and raise it

again, and someone would follow suit, and so it would

continue. The proclamations would sometimes continue for

three-quarters of an hour to an hour. In most instances, they

would give up and cease after they, even the wealthy elites,

had no further strength for the competition.

would

only go

to pray on

Rosh

Hashanah

and

Yom Kippur, would purchase their “seats” for the High

Holidays. Here there was ongoing

“class warfare,” especially on Yom Kippur – and almost every

Yom Kippur. On that day there is, as you know, a very

important “Maftir”

reading called “Maftir Jonah” and whoever “purchases” Maftir

Jonah is himself very important

and highly honored. The money collected for this acquisition

is then used for various things in the synagogue

but also for other matters such as Keren Kayemet [JNF], Linat

Hazedek [a charitable organization for the ill described in

more detail in the chapter] and more. The well-to-do of the

town would always sit by the eastern wall

which is closer to the rabbi. These were the wealthy

merchants, landlords, and people like themselves. In the last

row of benches sat those rich enough but not elite enough –

butchers, tailors and the like. And the battle was waged

between the last row and the eastern wall as to who would

deliver “Maftir Jonah.” From the eastern wall someone would

proclaim his price for the maftir. Immediately the opposition

answered from the butchers. For the most part, it would be the

butcher, the successful butcher, whose shop was on Beit

Midrash Street. When the golden prize would be declared at the

eastern wall, he would raise it by half a gold coin. And at

once they would jump up from the eastern wall and raise it

again, and someone would follow suit, and so it would

continue. The proclamations would sometimes continue for

three-quarters of an hour to an hour. In most instances, they

would give up and cease after they, even the wealthy elites,

had no further strength for the competition.

It was like that year in and year out with the class warfare between the distinguished ones with their yicchus [lineage] and those who, by way of their money, aspired to be in that position. This little war between the privileged of the eastern wall and those sitting in the last row of benches went on with another event – for the opening of the holy ark for “Neilah.””

Photograph of the

interior of the Yefeh 'Einayim wooden synagogue on page 169

of the Bielsk Podlaski Yizkor book. The caption reads:

"Photographed in 1919 by a Christian German soldier

who was impressed by the beauty of the building." The 1973

book "Rabbi Areyh Loeb Yellin, Author of "Yefeh 'Einayim"" by

Rivka Ziskind,

dates this photo to 1921. Another source states that holding

the Torah scroll is Elie Korytski,

Rabbi of Bielsk Podlaski. He would have served under Rabbi

Moshe Bendas who became the head Rabbi in 1917. Photo

contributed by Tomy Wisniewski.

The same chapter tells us that the Yefeh 'Einayim Synagogue:

“… was the shul for the elites, the grand figures of the city, and even its place and form indicated that. It stood on a high location in the center of a spacious garden with fruit trees and with benches for resting, and so forth. The windows of the building were wide, the ceiling of the hall was supported by pillars, but the holy ark was “modern” as in every other place.”

Photograph of the exterior of

the wooden Yefeh 'Einayim synagogue in Bielsk Podlaski,

taken during the interwar period.

The photo is on page 218 of the Bielsk Podlaski yizkor book,

in the chapter titled The Life Story of R' Aryeh Loeb

Yellin.

Below is a portion of a hand drawn map by Libe and Bashe Kleszczelski. It shows the Yefeh 'Einayim Synagogue as described above, adjoining a large green space with trees. Click to see the full map.

As mentioned

earlier, at the end of WWI “the three synagogues that were

concentrated on one square were burned.” A photo in the

chapter Yefeh Ha 'Einayim [The Beautiful Eyes] shows the

reconstruction of a Beit Midrash. Whether the photo shows a

more modest reconstruction of Yefeh 'Einayim or some other

building is unknown. A photo on the Yad

Vashem website

identified as “Bielsk Podlaski, Poland, 1962, The former “beit

midrash,” house of study,” looks very similar. However it

should be noted that all of the accounts below state that the Yefeh

'Einayim Synagogue did not survive the holocaust.

From Yefeh Ha ‘Einayim [The Beautiful

Eyes], in the Bielsk Podlaski Yizkor book.

The caption reads: "After the fire, the Beit Midrash is

rebuilt."

The Yefeh 'Einayim Synagogue was within the boundaries of the ghetto created by the Nazis in 1941. It served as the headquarters of the Judenrat (Jewish Council established by the Nazis) and the meeting place of the Jewish police. From time to time the Germans stormed the building. The approximate boundaries of the ghetto and locations of the Jewish sites within it can be seen on this map.

In the chapter In the Holocaust in Russia and also Bielsk Before and After its Destruction, Yehiel Chrabolowski wrote that after WWII "I heard that the central Great Synagogue was dismantled and its parts were sold." Another story is that the synagogue was dismantled because the wood was needed to construct the wall that the Jews were ordered by the Nazis to build around the ghetto. In this story about the discovery of a Torah scroll in Bielsk by the family of Moshe Alpert, who wrote three chapters in the yizkor book, it is said that Jews were herded into the synagogue which was then set on fire.

As sad as they are individually, these accounts are not mutually exclusive.

Acknowledgements

It would not have been possible to write this without the translators of the Bielsk Podlaski yizkor book. Each translated chapter has the name of its translator below the title. The translation of the Hebrew section of the book is at this time a work in progress. Every chapter translated sheds new light on the people, places, and events in the Jewish history of Bielsk

Thanks also to everyone who has contributed materials to the Bielsk Podlaski KehilaLinks site. Contributed maps provided corroborating information about the location of the synagogues, especially the Shaarei Tzion Synagogue.

Last

but

not least, thanks to the Polish National Archives, Archive of

New Records, Warsaw, Poland, for providing the scan of the

Shaarei Tzion Synagogue architectural plan.

Notes

1. Rabbi Ben Zion Sternfeld - See The Rabbi Bentzion son of the Rabbi Aryeh

Leib Sternfeld. For a story about Rabbi Ben Zion

Sternfeld having unsuccessfully avoided being photographed,

read Bielsk - Its Rabbis,

Teachers and Jews.

2. Bergman, Eleonora. 2011. “Strictly Polish: Synagogues of the Early Twentieth Century.” Jewish History 25 (1): 103–120. Special issue on Synagogue Architecture in Context. Published by Springer Nature.

3. Rabbi Moshe Aharon Bendas - See page

170 Rabbi

Moshe Aharon Benda’at, The Last Rav of the Community of

Bielsk Podlaski.

In

addition

to reading the Bielsk

Podlaski yizkor book

and the Bielsk

KehilaLinks site,

if you would like to read more about the cultural and

political environment in Bielsk Podlaski and the shtetls of

Europe as the clouds of antisemitism were growing, I recommend

An Unchosen People, Jewish Political Reckoning in Interwar

Poland, by Kenneth B. Moss. It relies heavily on

translations of an autobiography

written in the mid 1930s by a young man from Bielsk who

wrote under the pseudonym of Binyomin

Rotberg. Google Books offers a free

preview.

Book reviews can be read here and here. If

you read Yiddish, Rotberg's handwritten autobiography can be

read online or downloaded at the Center

for

Jewish History website.

Back to Bielsk Podlaski Home Page

Updated

March 6, 2025

Copyright © 2023 Andrew Blumberg

JewishGen Home Page | KehilaLinks Directory

This site is hosted at no cost by JewishGen, Inc., the Home of Jewish Genealogy. If you have been aided in your research by this site and wish to further our mission of preserving our history for future generations, your JewishGen-erosity is greatly appreciated.