Berlin, Germany

Blogs

Compelling Stories: Jewish lives lived

Posted: 04 Jan 2015 09:00 PM PST

"Berlin Childhood around 1900 is perhaps an even more important book today than when it was written." from commentary by Jeffrey Lewis as part of the You Must Read This series on National Public Radio website, May 28 2012

Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) wrote the pieces included in this volume in the 1930’s when he was no longer living in Germany. Published in 1950, ten years after his death, Berlin Childhood around 1900 includes some pieces first published in German newspapers, but during his lifetime the manuscript as a whole was rejected by several publishers.

Before exile, Benjamin had lived in Berlin, the place of his birth, having been raised in the West End in a prosperous, assimilated German Jewish family. He was a part of the vigorous intellectual life in Germany that was destroyed by Hitler.

In these pieces Benjamin re-examines his childhood from a sensual, impressionistic point of view, a literary style much like Marcel Proust employs in his autobiographical fiction. Benjamin was, in fact, a translator of Proust. Benjamin realizes his home, his city, his native country, have been taken from him, so he sets out to re-create many aspects of his childhood so that he can hold on to them. In transferring memory to paper, he leaves behind an eye-witness account, a poetic inventory, of a home and a city that were soon to be destroyed.

The poignancy of his account resides in the innocence of the protected, privileged child he had been whose perspective and experience he re-inhabits in order to write these vignettes. For example, in a section entitled Society, he discusses in some detail a large oval piece of jewelry his mother owned and the pleasure he got out of watching her take it out of the jewelry box and her wearing it on the nights she and his father had social engagements. He remembers it not only as a gem, but as a talisman that he believed kept both him and his mother safe.

As he is writing in the 1930’s about times and places that he treasured, he is aware of the external threat of Hitler’s rule, and we come away with a pervading sense of loss. We know the tragic outcome. -

This volume also includes an introductory essay by the translator, Howard Eiland.

To read a review of a biography of Walter Benjamin published in 2014, click here.

To see a photo of Benjamin's headstone in Portbou, Spain click here.

To read account of his death, click here.

People

Georg Benjamin – brother of Walter

Walter Benjamin

Dora Benjamin – sister of Walter

Places

Berlin, Germany

Compelling Stories: Jewish lives lived

by Toby Anne Bird

Posted: 01 Dec 2014 06:30 PM PST

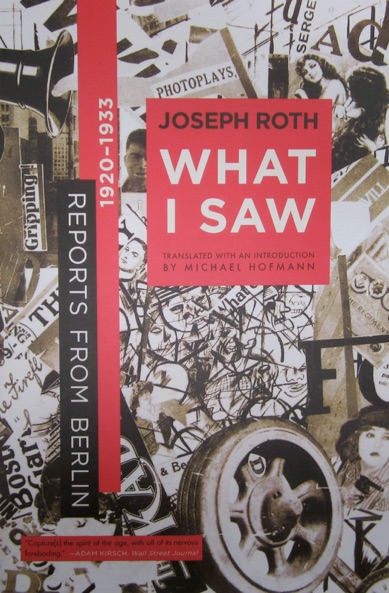

"It’s not only what Roth sees; it’s what he sees through. And often he sees unknowingly into the future we inhabit beyond his time." from a review by Nadine Gordimer in The Threepenny Review Spring 2003

Joseph Roth, a journalist and novelist born in Galicia in 1894, arrived in Berlin, Germany in 1920 after first living in Vienna. In this volume Michael Hoffman brings together 34 of Roth’s journalism pieces written between 1920 and 1933 which he has translated from the German. He also includes an informative introduction which includes biographical information about Roth and places him in the context of the Weimar Republic. And he provides footnotes so as to help us understand an occasional obscure reference. Also included are many photographs and illustrations.

Grouped according to subject matter in this volume, Roth’s topics give an impressionistic feel for the Berlin between the wars. His point of view is that of the outsider – someone who lives in the city and knows many of its quarters well, but at the same time he looks at the city, its residents, its architecture, its infrastructure, its cafes and night life with “new” eyes.

An assimilated German Jewish intellectual, Roth chose to write about Berlin’s Jewish quarter and he wrote sympathetically, but at a remove. He describes its residents who are refugees from the East, their difficult living conditions, and the lure of Palestine for those who wander homeless. He is quite passionate in his opinions and upset at their plight, but although he was himself born in Galicia, it is clear he sees them as “other.”

According to Hofmann’s introduction, in 1925 Roth made Paris his new base although he still spent time in Berlin and continued to write for the German newspapers until the Nazis came into power in 1933. The pieces included in this volume written starting in 1924 seem more engaged and more consistently political. One piece laments the murder of Walter Rathenau, a German Jew who, serving as foreign minister, was killed by right-wing extremists. Another, entitled “An Apolitical Observer Goes to the Reichstag,” is a cynical, critical look at the members of the German parliament. In the course of the piece he criticizes the seeming paralysis of the various political parties, each representing its own interests. And he ominously refers to “[t]he goose-stepping of the Nationalists.”

The most powerful piece in the collection because of its subject and Roth’s engaged fury is the last one included, “The Auto-da-Fe of the Mind,” published in French in the September/November issue of Cahiers Juifs (Paris). The title, deliberately echoing the barbarity of the Spanish Inquisition, is at one and the same time a piece written to protest the enormity of the burning of books of German writers who the Nazis considered “degenerate,” many of them Jewish, and to protest the expulsion from Germany of German Jewish writers (including Roth, of course). In the piece he gives a brief history of entrenched German anti-Semitism and praises the many German Jewish writers whose books were burned, listing more than three dozen alphabetically (from Altenberg to Zweig). But most importantly, he uses the piece to alert the world, to try to get the world beyond Germany to understand the implications of what was happening. This piece is horrifying to read now, given that we know the outcome.

People

Roth mentions no family by name. The translator Michael Hofmann supplies some background about Roth's family in the introduction.

One piece is a tribute to Walter Rathenau. In the final piece, as stated above, Roth lists and characterizes each of about three dozen German Jewish writers.

Places

Berlin

To watch a video about the book burning in Germany, click here.

To read a timeline that covers Berlin history and its Jewish residents, click here.

Berlin's Hummus Entrepreneurs