Ryszard Majus Remembers

I am starting to write my story on Thursday, April 29, 1992葉he Day of Commemoration of the six million European Jews who were killed in the Holocaust. I am writing in Polish because, in this language, it is easiest to formulate my thoughts. I hope that the day will come when someone will translate this into the languages known to my grandchildren, Hebrew and English. This story is written for them. This will be a story about our family, a history about people of whom nothing remains except that which lives on in my memory. Every person has a name. Today, these names are being called out. I shall call these names out here葉he names and characters that carried them. Nothing of theirs has remained to me溶either an object nor a photograph容xcept for a photograph of my father, which was sent to me from Australia. I would like to preserve them from oblivion. This is my duty, since I was the only one who survived the Holocaust. I am already 68 years old, and this is the last moment for me to start writing. Once a small town, Wielkie Oczy is now a village on the border between Poland and Ukraine, next to the city of Lubaczow. One needs a detailed map of Poland in order to find it. There I was born. There I passed my childhood. There in the cemetery are buried my grandparents who were lucky to die a natural death before German and Ukrainian fascists killed the whole Jewish population of the town in 1942 - 1943. Among these were my parents, Avraham and Golda (n馥 Silberstein), my brother Yossi, my uncles and aunts, and my friends from school. I would like to write a few words about this town and about my parents' home. Wielkie Oczy

|

|

The synagogue in an undated photograph. (ゥ Yad Vashem, courtesy of The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority, Film and Photo Department, Archives, Israel.) |

Across the road was the synagogue. It was a large white building, of which the whole community was proud. The synagogue was built with the aid of contributions from American Jews who had originated in Wielkie Oczy. The old Beit HaMidrash was destroyed during the Nazi occupation in 1943. On the other hand, the synagogue still stands today. I saw it with my own eyes when I was there after the war. Today, it serves as a grain warehouse of an agricultural co-operative. Prayers were held in the synagogue only on Sabbaths. It was cold there in winter, because there was no heating in the building. Weddings were held on the steps of the main entrance, and there stood a canopy. There, on the way to the cemetery, they also stopped for prayers during funerals. Every wealthy Jew had a permanent place in the synagogue. The most honorable places were next to the eastern wall, next to the Holy Ark. My grandfather, the late Israel Majus, had his place there. I spent many hours of prayer with him there. The synagogue had windows of colored glass. A festive cold prevailed there. The platform was made of wrought iron and upon it stood a large candelabrum. On this platform, facing eastwards, stood the cantor or someone else who was leading the prayers. Next to him, there was a place for the rabbi. In my memory, I see a curtain of purple velvet, embroidered with letters of gold, which covered the Holy Ark. Within the Ark were the Torah scrolls. This curtain was donated to the synagogue by my uncle, the late Leon Majus, on the only occasion that I remember when he came to visit us from Vienna, where he was permanently living.

The Jewish community of Wielkie Oczy had its own rabbi, as well as a ritual slaughterer, who used to slaughter chickens and cattle for the local butcher. The rabbi and the slaughterer lived next to each other near the synagogue. In a neighboring house, lived a family who had a special license to bake Passover Matzos for the Jewish community. There was also a machine for grinding matzo meal.

There were no Chassidim in Wielkie Oczy. The Jews wore beards, while the religious Jews wore beards and side-curls. Some of them had long beards and some of them, like my grandfather, had short beards. On Sabbaths, on the way to the synagogue, they wore fox-fur hats (shtreimel) or, like my father, a hat. Side-curls were compulsory for every Jewish boy and for every adult. When I had a haircut, they always left me side-curls next to the ears. I did not know anyone who did not have side-curls.

On Saturdays, Sundays and Christian holidays, the Jewish shops had to be closed. Generally, Jews, Ukrainians and Poles葉he whole population of the town様ived amicably. Everyone knew everyone else. I do not remember any anti-Jewish incidents. On the other hand, slogans were frequently written on the walls. These slogans mocked the Jews or called for the boycott of Jewish shops. They also demanded of the Jews to emigrate to Palestine. Here are some of the graffiti which I remember from my childhood: "A long life to all those who beat Jews", "Jews to Palestine", etc. Children in the class used to shout (a very free translation): " A Jew has two balls. A tiger comes and bites them. A lion comes, drinks blood, and the Jew dies".

Ukrainians who had lived in Galicia in Eastern Poland between the world wars dreamt of an independent Ukrainian State. They had official and underground nationalist organizations against which the Polish government fought. School children used to shout: "Here is a hill and there is a valley. Behold, this is below and is not Ukraine" All of this was thought of as being natural, and people did not take it seriously. On Succoth, every Jewish family set up a tabernacle. These tabernacles were excellent targets for non-Jewish children, who threw stones on them when we ate our festival meals there.

There were times when a tzaddik or a bishop came to Wielkie Oczy. For the visit of a tzaddik, the whole Jewish community used to prepare ahead. A canopy was constructed and carried by four men so that he should not, G-d forbid, get his shoes dirty with mud. The tzaddik generally came from the direction Lubaczow. They waited for him with the canopy on the outskirts of the town, and the whole Jewish population would accompany him to the rabbi's house and the synagogue. The rabbi would come out of his house wrapped in a tallit in order to receive the tzaddik. Jewish youths on horses acted as a corps of accompaniment for the tzaddik. In order to honor the tzaddik, he was also received by the mayor and the local priest, accompanied by distinguished farm owners. The Catholic bishop was also received in a similar way when he came to visit the town. The bells rang in the Catholic and Greek-Catholic churches. Jews went out to the outskirts of the town with Torah scrolls. The bishop used to come out from the canopy and kiss the Torah. On Jewish holidays, during prayers at the synagogue, the mayor used to come for a short visit, especially when a prayer was said for the Polish President Ignacy Moscicki, or Marshal Pilsudski. In the prayer books printed even before WW I, there were prayers for the ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire Emperor Franz Joseph. All of those who prayed, most of whom did not understand the Hebrew version of the prayer, prayed to God for health and long life for emperor Franz Joseph, even though he had been dead for quite a while.

As time went by, when they began to develop anti-Jewish propaganda and activities in fascist Germany, nationalist parties and groups in Poland also adopted fascist ideologies and conducted anti-Jewish pursuits.

We, the Jewish boys, were not allowed to belong to the Scouts. I envied my friends who went to their meetings in Scout uniforms. We were also not allowed to join the Strzelec organization, in which older boys trained with rifles. We made wooden rifles for ourselves and we imitated them. At that time, an Agricultural Association was set up, which opened shops in competition with the Jewish shops. On the walls appeared slogans such as "Do not buy at Jewish shops" and "Poland for the Polish". This was a sign of warning of what was to happen in the near future. Unluckily, however, no one in the town was aware of this.

Home and Family

House No.2 was a single-storied house, constructed of red bricks and stood on the square. It had five small rooms. Behind the house were a vegetable garden and a small courtyard. On the courtyard side was a summer kitchen, called a "balcony". Stairs led from here to a room on the roof. Two rooms had windows facing the square. Two others, of the same size, had windows facing the courtyard. The kitchen, without a window, was in the middle of the house, and separated the frontal section from the section next to the courtyard. The house had two entrances, one from the square and one from the courtyard. The entrance from the square led to the shop. From the shop, it was possible to enter the room of Grandpa and Grandma Majus, as well as the kitchen. From the kitchen and the courtyard were entrances to our parents' room and the bedroom. From the shop, through an opening in the floor, there was an entrance to the cellar. Above the entrance to the shop was a small bell that rang when someone opened the door. This announced the entrance of every customer into the shop. At first, we sold textile products in the shop, which were later replaced by haberdashery, because this merchandize required less working capital. Soon before the outbreak of war in 1939, we sold only tobacco and cigarettes. The shop was, or was supposed to be, a source of livelihood for the whole family. There were a number of shops like this in the town, which competed with one another. The customers were the local population as well as the farmers from the nearby villages.

Family life was centered in the kitchen. Most of the space in the kitchen was taken up by an oven for baking bread and an oven for cooking. Above the second oven was a smoke collector, which led to a chimney. Despite the fact that the kitchen was the darkest of all the rooms in the house, we ate all our meals there at the table, and everyone had his preset place. We used to sit there on long fall and winter evenings, by the light of an oil lamp. There, I did my homework. It was warm there because of the bread and cooking ovens. We did not heat the other rooms, in order to save on wood. The kitchen also served as a bathroom since, there were a washbasin and a bucket of water. Before festivals and, of course, before the Passover we used to wash in a tin bath, which was brought down from the roof-room. Excretions were done in the wooden toilet that stood in the courtyard. At night, we used a chamber pot. In winter, the temperature would reach 20 degrees below freezing, and snow would cover the square, the streets and the fields. In the house, it was so cold that the water in the buckets froze. Strong winds blew tiles off the roof and snow fell through holes into the room on the roof. This snow had to be collected and thrown out before it melted and wet the ceilings. Father never hit me, but once during winter, when he asked me to help him to collect the snow and I refused, I received such blows that I remember them until this day.

We were very poor. My friends had beautiful snow-sleds, manufactured by a carpenter. I had a sled that my grandfather made. The blades of the sled were made of wood. I was ashamed that I had such a sled, but what could I do? I used to slide from the top of a small hill next to our house. I was too scared to slide from a higher hill near the brewery.

I never had new clothing. I always wore clothes that mother stitched from adult clothes. Mother had a sewing machine, which she used to sew and repair clothes for the whole family. My first new shirt that was bought in a shop with money that I earned when I was 13 by giving extra lessons. In the fifth grade, I received a used leather case for school as a present from my father that father had bought at the market. Until then, I had carried my books tied with a lace. I still see this case before my eyes to this very day. I was proud of it. In the corner of the shop stood a small rough wooden cupboard built by grandpa. In this cupboard, grandma used to keep homemade candied preserves. She sometimes spread them for me on a slice of bread and butter. The cupboard was always locked. Father once prepared an excellent present for me. He once ordered a bookcase for me from the carpenter. The bookcase had one drawer and two shelves. The bookcase stood next to my bed and had a smell of fresh paint.

I had two grandfathers and two grandmothers. The name of

the "more important" grandfather was Israel Majus. He was called

Srul. He was tall and thin. He had a beard and very small side curls and

always wore black or gray clothes. He smoked cigarettes wrapped in Soleli

papers. He used to divide each cigarette into two. He then poured the

tobacco into cigarette paper and rolled two new cigarettes. On Friday

evenings and on Saturdays, he used to walk hand-in-hand with me to the new

synagogue. He used to wear a long black coat, tied with a black velvet

lace. He taught me how to hold a hammer, how to hammer nails. Together

with me, he used to make toys from pieces of wood in the courtyard. I

never asked him about his childhood, who his father and his grandfather

were, and from where they came to Wielkie Oczy. Grandpa spoke German very

fluently. At home, on the bookcase, were German books, generally printed

in Gothic characters, some of them with drawings. I am very sorry that I

know nothing about my grandfather. He never told us anything about

himself. In the kitchen, he had a permanent place at the table. After

every afternoon meal, he used to drink tea from a thick glass, which he

held with both hands. He passed away a few years before the war and was

buried in the Jewish cemetery in Wielkie Oczy. He was a Levite.

The name of Grandpa Israel's wife, my grandmother on my father's side, was Elka. Thus, she was called. She was shorter than grandpa and she had her own hair; she did not wear a wig like other Jewish women. During that period, as well as among religious Jewish families today, a woman shaves off her hair immediately after the wedding ceremony, and wears a wig. My mother also had her own hair. Granny Elka wore pince-nez spectacles with a metal frame held on her nose. Grandma often made comments to me. I remember one occurrence until today. I took a stick and drew various drawings on the ground in the courtyard, which grandma had previously swept. So I heard her say, "You've destroyed the floor".

The names of granny and of my aunt Rosa, who passed away in Switzerland before I was born, were used as a family code for indicating prices in our shop. With their help, we encoded minimum prices, below which there was no profit. The letters in Granny and Auntie's names represented the digits from 0 to 9, such as:

During the bargaining with clients, each member of the family knew for how much each item could be sold. Granny passed away before the war, a year after grandpa. Like grandpa, she died in her bed. She is buried next to Grandpa in the Jewish cemetery.

The name of my grandfather on my mother's side was Solomon Silberstein. His wife's name was Rachel. This was Grandpa Silberstein's second wife. In other words, I never knew my real grandmother, my mother's mother, since she had passed away before I was born. Grandpa and grandma Silberstein lived in Wielkie Oczy in a wooden house on the road that led to the Catholic cemetery. Next to the house grew a pear tree which yielded many tasty pears. Grandpa Solomon had a short red beard. Grandpa dealt in the marketing of furs. They had two sons, my uncles. The elder son, Zelig, was the most educated person in Wielkie Oczy because he was the only one who had passed the pre-matriculation exams. He worked as a secretary at the town council and he thus had the status of being almost a government official. His brother Yossie assisted Grandpa Solomon in the fur trade. Grandpa Solomon passed away before the war. His wife Rachel reached the northern part of Russia, the Komy Republic, in a roundabout way. There, she apparently passed away. During the Holocaust, my uncle Zelig and his young wife died near Lwow. He had married her just before the outbreak of war. His brother, my uncle Josie, also died there.

The only one of my close family who survived the Holocaust was another son of Grandpa Solomon, my mother's brother, Emmanuel Silberstein. He survived because, before the war, he had lived in Berlin and had managed to flee to the USA, together with his wife Sally, before the persecutions broke out.

The End...

On the first day of war between Germany and U.S.S.R. on June 22, 1941, German troops crossed the neighboring San river and entered Wielkie Oczy.

In July, 1941 the German's formed the town administration and the police, staffed by local Ukrainians. There was also a Judenrat formed. The head of it was Wolu Taler. It is then when persecutions of Jews started.

Particular cruelty was exhibited by the chief of the German police from Jaworow, a man named Wolf. His favorite occupation was scaring Jews with his German shepherd dog with which he never parted. Particular persecutions were meted out to those fathers of families whose sons or daughters were able to flee east to Russia before Germans entered. Victims were tied to a post in the town square and beaten without mercy. The executioners were the Ukrainians from the local police precinct. In this way they murdered the local tailor, Srul (Israel) August, whose three sons escaped from Germans to Russia. Those sons are Joseph-Ber August, Abraham August and Majer August. At the head of the Ukrainian Gmina was Smutek as the wojt (leader) and Bulycz as the secretary. Every several weeks Wolf arrived in the village along with his German administrators to collect "contributions" in the form of jewelry, furs, etc. from the Jewish Gmina . In the fall of 1941 the young and strong men, per the list provided by the Judenrat, were taken away to an unknown destination, probably to the camp Janowska in Lwow. In this camp my father Abraham Majus died in 1943.

In June 1942, the entire Jewish population was summoned to the town square. Each person was allowed to take along only what could be carried, and they were force-driven to the ghetto in Krakowiec. The old and sick were carried on the farmers wagons. Jewish homes were sealed. The distance to Krakowiec is 7 km. On the way, those who could not keep the pace were beaten with cruelty by one Ukrainian policeman in particular, a mute from village Horysznie, called Iya who was armed with a club. After taking down the ghetto in Krakowiec, those who survived famine and diseases were re-settled to the ghetto in the former district town of Jaworow. There they collected the Jewish population from the vicinity. The ghetto in Jaworow existed until 1943. Residents of the Jaworow ghetto were killed on the spot, shot in groups in the nearby woods. They were buried in a common grave.

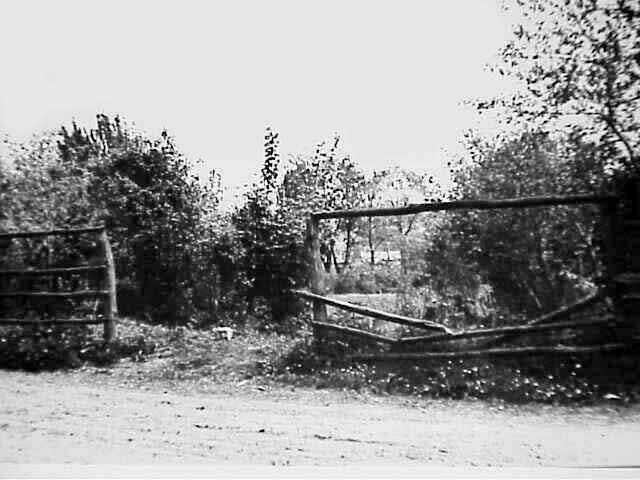

|

The Jewish cemetery gate, Wielkie Oczy in a photograph dated 1964. (ゥ Yad Vashem, courtesy of The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority, Film and Photo Department, Archives, Israel.) |

Those residents of Wielkie Oczy who escaped and were able to hide in the surrounding woods were captured. In 1943 a group of 9 was captured, among them 3 women and 3 children. All were shot and buried on the Jewish cemetery in Wielkie Oczy. Among the victims were Bajla Karg, 26, Chaim Grosman, 30, and Meir Mazym. At the end of that year, another group of 12 was captured. Those too, were shot and buried on the Jewish cemetery.

In the ghetto in Jaworow, among others, my mother Golda Majus and my brother, 12 year old brother Joseph Majus died.

Four young Jews, men from Wielke Oczy, who survived to the end in the woods, after entrance of the Soviet army returned to their homes in Wielkie Oczy. These were killed by a local bandit, a Pole. Among them there was also my neighbor Joiny Richter.

The local Ukrainians, members of the police and others, were taken to Siberia by the Soviet government. Just before the Soviet troops entered, the local UPA bandits set the village on fire. Many Jewish houses were burned, especially the wooden ones. The remaining ones, the brick ones, were taken by the Poles. The old synagogue was taken apart for bricks. The new one still stands today and is used for storage. All tombstones were stolen from the Jewish cemetery. They serve as sidewalks and steps to many houses. They are covered with concrete and hidden from view. The very area of the cemetery in 1985 is a picture of a lot grown over with wild bushes.

Ryszard (Reuven, Ryzio)

Majus

Tel Aviv, 1992

Back to KehilaLiinks Page--Wielkie Oczy | Jewish Gen Home Page | KehilaLiinks Directory

Copyright ゥ The Wielkie Oczy Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved.