THE PTAK FAMILY (Vengrov, 1935)

Front row, l-r: Srul Usha, his daughter, Tsivya, Moishe, Pesach

Back row: Rivim, Leibl, Srul Usha's wife Ruchel,

Moishe's wife Sura, Clara, Michel Zewica

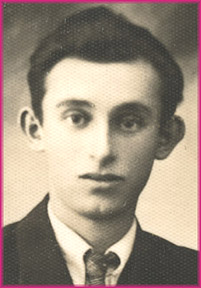

Leibl (Leo) Ptak (Vengrov, 1935)

I want to tell you a story. It isnít from a book ó it happened to me. It is about my life in Vengrov, a small town near Sokolov in Poland, where I was born. According to tradition, Vengrov was one of the oldest towns in Poland, about 800 years old. It was a typical Yiddish shtetl. We had our rabbis, Hasidim, political parties, and plain and simple Jews. There were communists, Zionists, Bundists [members of the Jewish Labor Union], and more.

My Family: My memories about us as kids are vague and fuzzy and are fading like a photograph. My two half-brothers (same father, different mothers) lived with us. The older one, Moishe, was a businessman and helped to run our shoe store. His brother Srul Usha [Sol] worked at the bench making boots and repairing shoes. My mother was my fatherís second wife and they had four children together. Our sister Chaika [Clara], the only girl, was pretty and popular with boys. Her boy friend was Michel Zewica. His family dealt in wheat. They lived in a brick one-family home and were considered rich. Then came me, Leibl [Leo]. Next was our brother Rivim [Ruby], who was a sickly child who always was catching something. He joined the Zionist party and had his own friends. The youngest was Pesach [Paul], who was a solid, good little boy who clung to himself.

Front (l-r): Rivim, Pesach. Back (l-r):

Leibl, Chaika. Vengrov (1930)

My dear mother gave birth to all four of her children in the house where we lived. Mom suffered intolerable pain and clawed at the walls and her screams rose to the heavens as I watched her giving birth to my brother Pesach. The house was crowded with women boiling pots of water. The baby was born still and silent. A woman held his feet upside down, smacked his tush, then dumped him in cold water. He was born on Passover.

My father, Hersh Isak Ptak, was tall, a handsome man, kind and shy. In Vengrov, people referred to him as der grosse Hersh Izik, "the tall Hersh Isak." Dad wore a professorís black beard. He wasnít frum, but he attended shabbes services and I went with him. One seder night, I was sitting next to him, mumbling and pretending that I was following the prayers. My father turned to me and asked, "What page are we on?" I spread my fingers on a page. He knew I hadnít been paying attention and smacked me across the face. It was the first and last time that he hit me.

I have only cloudy memories of our dear father from when I was a child. He went to America when I was nine and Pesach was only one or two years old. We were apart eight years. He didnít abandon his wife and children like so many others did. My father, alone and lonely in America, said that he loved and needed us and longed to be reunited with us. I loved him so.

Ruchel Ptak, my grandmother

Our Grandma Ruchel ó Dadís mother ó was a widow in her late sixties. She went begging from door to door, store to store, house to house. I never understood why. [Perhaps she was raising money for charity.] Dad had two brothers. The oldest was single, lived in Warsaw, and often came to visit. The youngest was a hard-working shoemaker who was married, had two sons and lived in Vengrow. He died suddenly, perhaps from a heart attack, and left his beautiful wife and two young boys alone.

My mother Tsivya lost her parents when she was very young and we never knew them. After her parents died, my mother went to work cleaning houses. She had two sisters and a brother. Both sisters died young, one in childbirth and the other when her hair caught fire. One of Momís sisters was married to my father. When she died, Dad married Mom, his sister-in-law, who was only 16 or 17 years old. Momís brother Chaim, a shoemaker, was a sick man who had tuberculosis. He was married and had many children. One of his daughters, a lovely child, was born a deaf mute. They stayed in Vengrov and they all died in the Holocaust.

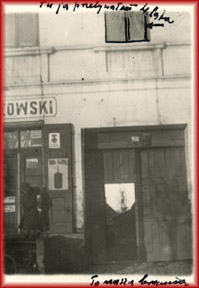

Front (l-r): Our home above the store in Vengrov

Our Home: We didnít live in a house, but in one long room above the stores. At best, it was a poor manís flat. On either side of the window stood a bed for my parents and a bed for my sister Chaika. Along the walls were cots for us boys and under the cots we saved potatoes for the winter. When I was little, I shared a cot with my brother Moishe. I loved rubbing his face before he shaved. I stayed awake until he came home from the dates he had with his beautiful girlfriend. She had a lovely figure, dark hair, black eyes, and an Indian-looking face with high cheekbones. She was exotic.

We never had telephones or pipes with running water. For washing, we used rainwater that we caught in barrels. We didnít have indoor showers or toilets. The outhouses were in the backyard. Our people in the shtetls didnít know anything different. But we did have butchers, bakers, tailors, and shoemakers in our town. Some sons followed in their fathersí footsteps. In my family, the shoemakerís art was handed down from one generation to the next.

Vengrovís Religious Life: Rabbi Morgenstern, a son of the famous Sokolover rebbe, was chief rabbi of Vengrov. We had a beautiful big shul and many small shtiblach where yeshiva boys studied Torah. We also had a mikva [ritual bath]. On Fridays the place was packed with people. I snuck in once and dunked myself in the hot tub. It was an adventure for me.

The town had one Jewish cemetery. Only God knows how old it was. The stones were of every size and were covered with grass and overgrown with moss. The inscriptions were hard to read.

There was a kosher slaughterhouse on a side street in town. You brought a chicken and tied its legs, swirled it around your head three times, made a prayer. Then the shoikhet came with a sharp knife in his hands and slaughtered the poor chicken. The chicken flicker pulled out the feathers and the job was done.

My brother Srul Usha and his wife

One day, the Hasidim and others dressed in their holiday clothing and walked through the streets of the town carrying a chupah. The procession was accompanied by a two-piece band consisting of a fiddler and a trumpeter. Under the chupah was my brother Srul Usha, dressed in his finest clothes, walking to his brideís house to be married. Srul Usha's wife and their two children died in the Holocaust.

Anti-Semitism in Vengrov: Twice a week was market day in our shtetl. Farmers from outside of town came to sell their crops: potatoes, tomatoes, corn, wheat, etc. They bought shoes, boots, and salt from Jewish stores in town. I would look out of our window onto the town square and observe the whole panorama: row upon row of wagons and horses filled the square. Our window was a treasure to me, as I beheld this sight.

Then there were times, after business was done and the sun was setting, that screams were heard in the square and people were seen running. "You killed Jesus!" the drunken mobs of peasants would shout. No one stopped them. They terrorized the Jewish community and fear would lay over the town.

One Christmas eve, the town was covered with snow. The church across the square from our home was lit up and the Christians were gathering for midnight mass. Mom was awake. She made sure that the latch on the heavy door was down and tightly closed. She woke us up and we all huddled on the kitchen floor. The church bells began ringing and so was my head. Then the banging began on our door and the swear-words came: "You Jew bastards, open up. You killed my Jesus." Bang, bang. I was scared and holding on to Mom. She whispered, "Sha, sha, shtill." It was then that I learned what fear was.

The man at the door was a Christian neighborís son and he was drunk. He had eloped with one of the Jewish girls in town. When that happened, our poor shtetl was in mourning. The girlís brothers were friends of mine and it was such a shame on the family.

For the second part of Leo Ptak's memoir, click here.

Credits: Text and photographs copyrighted © 2008 by Leo Ptak. Text edited and page designed by Helene Kenvin. Page created by Helene Kenvin. All rights reserved.