THE PTAK FAMILY (Vengrov, 1927)

Front row, l-r: daughter of Srul Usha Ptak (name unknown),

Rivim Ptak, Pesach Ptak, Chaika Ptak. Back row: Chiel Nortman

(nephew of Tsivya Nortman Ptak), Leibl Ptak, Tsivya

Nortman Ptak, and (seated) Hersh Isak Ptak.

Pesach (Paul) Ptak (Vengrov, 1936)

I was born in Vengrov, a shtetl not far from Warsaw. There were some 5,000 people in the town, most of whom were Jewish and quite poor. The people were either shoemakers, tailors, tanners, or milkmen. We existed on very little: bread, potatoes and, on Shabbat, chicken and chicken soup. Our lives were marginal, but we accepted our lot because we knew no better way. We had each other and thatís about all we had.

My father, Hersh Isak Ptak, was born in Vengrov in 1888. He came to America in 1906, at the age of 18. He went to St. Louis, but could not make a living. So he returned to Vengrov to live the same miserable life he thought he had left behind. But at least he had his family and that was somehow comforting.

Two years after he returned to Vengrov, at the age of 20, my father got married. He and his wife had two sons, my brothers Moishe and Srul Usha (Sol). One day, my fatherís wife was cooking at the stove and her hair got caught in the flame. She was badly burned and she died from her injuries. My father was left with two small boys and his life was even more difficult. As was customary in those days, he married his dead wifeís sister, Tsivya Nortman. She was born in Vengrov on April 1, 1898 and was only 16 years old when they married in 1914. At that young age. my mother had a husband and two small boys.

My parents started a new family together. My sister Chaika (Clara) was born in 1916. Then came Leibl (Leo, born 1919), Rivim (Ruby, born 1923) and me. My entry into this world came on April 1, 1926, my motherís 28th birthday. I was born in their small apartment, with the help of the only doctor in the town. It was Passover and that is why they named me Pesach. With no television or radio or other diversions, what else was there to do but have children?

Rivim (Ruby) Ptak (Vengrov, 1936)

Our family was very poor. My father was a shoemaker and he stood on his feet all day and worked constantly, from early morning until late at night. He had very little contact with us children and not very much with my mother. He was out of the apartment before we woke up in the morning and at night he would come home late, have something to eat, and then go to sleep. Can you imagine how hard life was, with no future of any kind besides the thought of survival? I am told that my only toys were his old hat and a rubber ball.

My father could barely support his family of eight, but this story will tell you what kind of man he was. One day, he passed a little boy sitting in the street crying. When he asked the boy why he was crying, the boy said that his parents (who probably were even poorer than we were and couldnít afford to feed him) had thrown him out and did not want him back. My father felt sorry for this boy, whose name was Chaim (Hymie) Butcher. He took Hymie home with him and he lived with us a few years. With six kids, my father thought that another one didnít make much difference. Eventually, Hymie was brought over to America by an uncle of his. For the rest of his life, Hymie was close to our family. I knew him and his wife until they died some 50 years later.

After World War I and into the 1920ís, life in Vengrov was extremely tough. Anti-Semitism was rampant and our lives were in constant jeopardy. In desperation, my father went back to America. He arrived in New York in 1928, right before the Great Depression. While my father tried to make a living in New York, my mother was left with the responsibility of raising their large family in Vengrov. She owned a small shoe store in the middle of town and her customers were the Polish farmers who came to town twice a week to sell their produce. My mother was the rock of the family. Her whole life revolved around her children. She had a very hard life, but it was a happy one for her because she was involved in our lives.

I was two years old when my father left, so I didnít know him at all. My memories of the next eight years are mostly of playing with other children, my cousins, and my little dog, and going to a Polish school, where I learned very little. The Polish school was a bad experience because, as small children, we were always afraid of being attacked by the older Polish boys. When we got out of school, they would throw stones at us as we ran home and occasionally someone got hurt. One boy I knew lost an eye when a Polish boy threw a stone at him.

After I went to the Polish school, every day I went to Hebrew school or cheder, which I hated. I would sit with a bunch of other boys in a dingy, smelly, poorly lit room, with a teacher who did not know how to teach. Yiddish was the language we spoke at home, so learning Hebrew and Polish were major problems for me.

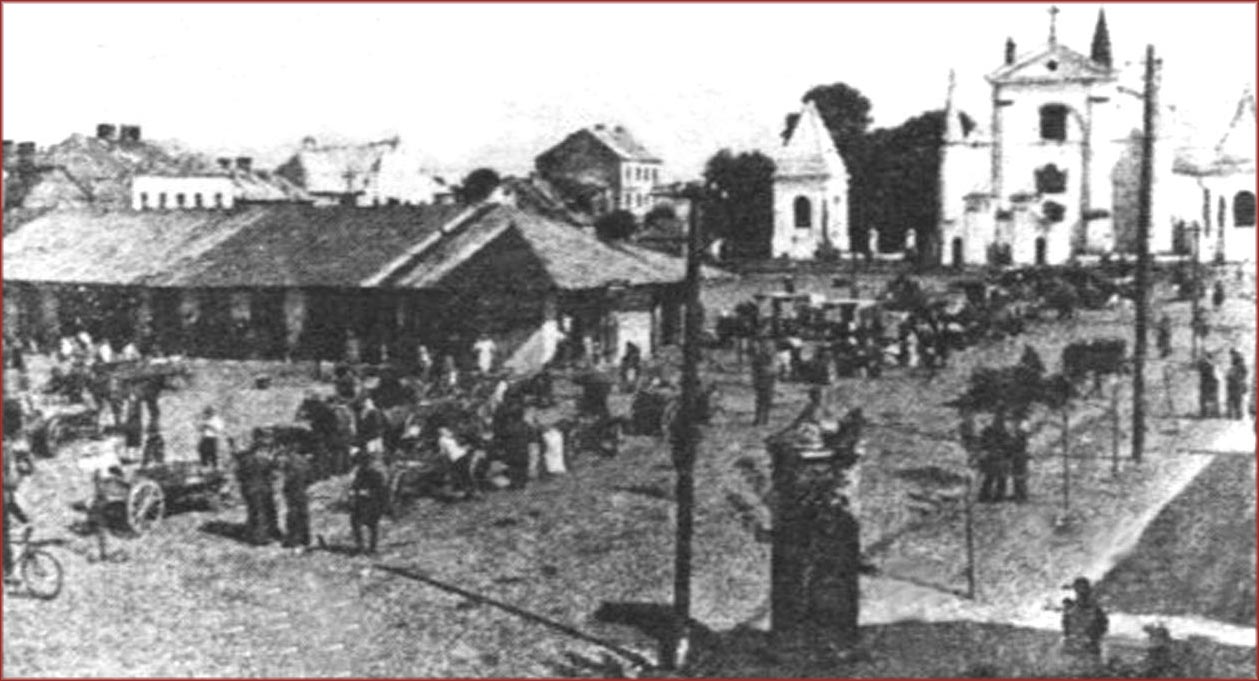

Vengrov's Market Square, with the church

across the square from where the Ptaks lived.

We lived on one side of the market square in town, facing the square. On the other side was the church, which took up the whole side of the square. My friends and I always kept our distance from that church and were afraid to go near it. We used to go swimming in the river about a half mile out of town and we played soldier. I also used to watch my brother Leibl playing soccer with his friends in a vacant field. One day, a Polish man came out from a nearby house with a big dog and chased all the kids away. Everyone ran except Leibl. He stood his ground, seemingly unafraid. Leibl and the Polish man confronted each other and finally, the man and his dog backed away. Leibl was all of 13 years old. The chutzpah of a young Jewish boy standing up to a mature Polish man with a big dog left an impression on me that I never forgot.

Living conditions and sanitary conditions in Vengrov were medieval by our present standards. We lived in one big, long room that was about 30 feet by 8 feet. It was a very narrow room, with a window facing the town square. There were no walls or doors. Half of the room was the bedroom, which had two beds. My mother and sister Chaika slept in one bed and we three boys used the other. In the front 15 feet of the apartment, there was a coal stove and a shoe repair bench that my half-brother Srul used. We had no running water. There was a well in the back, about 50 feet behind the house, that we and other people used. We had dirt floors and an outhouse about 100 feet in the back of the building. Remembering what my early childhood was like is a humbling experience for me. It makes me thankful for all the good things that happened to me along the way: my schooling, my business and, most of all, my family. I sometimes marvel at the good fortune that shaped my life.

Paul Ptak (2007)

For the story of the emigration of the Ptak family to America, click here.

Credits: Text and photographs copyrighted © 2008 by Paul Ptak. Text edited and page designed by Helene Kenvin. Page created by Helene Kenvin. All rights reserved.