The "Shkola" and Father's Shtreiml

by Jacob Wiesenthal z"l | |

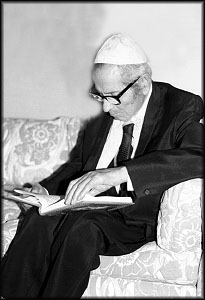

Jacob Wiesenthal, born in Skala in 1891,

in a photograph taken in 1978 |

Click on pictures to enlarge

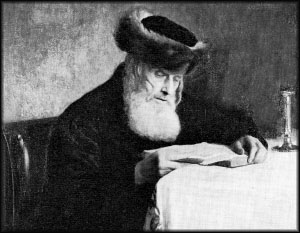

Scene from a typical European cheder or Jewish religious school |

When I was a young cheder student before the first World War, Skala and other Jewish communities in eastern Galicia were suddenly faced with a distressing government decree: all school-aged children must attend a state-run public school. Private tutoring with a teacher — which had been permitted until then — was not enough. One had to go to a shkola! |

The Austrian emperor Franz Josef really was a gracious ruler. He was good to the Jews; but going to a shkola --- he should not have done this. The Imperial Minister of Education maintained that all citizens of the empire, while enjoying many rights and freedoms, also were obligated to send their children to a shkola!

| This royal decree caused great turmoil among the pious and Hasidic Jews of Skala. Sending children to a shkola meant that they would be required to sit bare-headed, without a yarmulke, in classes with crucifixes hanging on the wall, be exposed to the babble of Christian children and who knows to what else? Perhaps they also would have to go to shkola on the Sabbath and, God forbid, desecrate the Holy Day of Rest? That could not happen! Pious Jewish children would not go to a shkola, no matter what! |

Emperor Franz Josef of Austro-Hungary |

My father, Reb Hirsh Eliahu, may he rest in peace, was also among the naysayers who said, absolutely not. The Municipal Education Administration eventually became aware of this opposition to the new decree and my father was singled out for punishment and fined by them. A fendung was issued by the city, that something of value had to be seized and confiscated from his house.

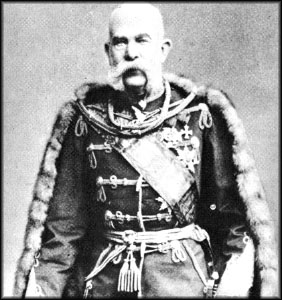

Scholar wearing his shtreiml |

Moshe-Yonah, the Jewish City Marshal who came to execute the fendung, deliberated and decided that the best thing to seize from my father's house was his shtreimel. But Moshe-Yoneh the City Marshal, himself a Jew with a beard and side curls who wore a shtreimel and long coat on the Sabbath and holidays, found a trick by which he could get out of the dilemma. |

How could he allow a Hasidic Jew like my father to walk out on the Sabbath and holidays without his shtreimel? So on the eve of every Sabbath and holiday, Moshe-Yonah brought the shtreimel back to my father's house and after Sabbaths and holidays he picked it up and returned it to the city hall. That is how Moshe-Yoneh enforced Franz Josef's statute for appearance's sake: both the Emperor and my father had the shtreimel.

| In addition to his official position as City Marshal, Moshe-Yoneh cared for the gravestones. He also took the trouble every Friday afternoon to inspect the eruv and make sure it was intact, so that observant Jews could carry things on the Sabbath. Moshe-Yoneh also watched to make sure that no one, God forbid, publically desecrated the Sabbath, that no woman, God forbid, carried a handbag or umbrella on the Sabbath. All Moshe-Yoneh had to do was raise his eyebrow or open his mouth and any woman who dared to do such a thing immediately ran away, straight as an arrow from a bow. But seldom, very seldom, did anyone dare --- not in Skala --- not in those times ... |

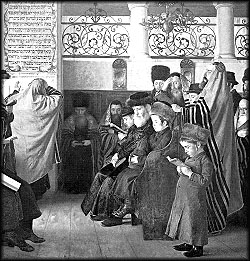

Synagogue scene showing men wearing shtreimls |

Was there really such a shtetl as Skala? Or perhaps it is only a dream.

Note: A fendung is a German legal writ issued to ensure that someone complies with a court order. A bailiff will go to the person's house with the fendung, to see if there is anything of value that can be confiscated. In modern times, rather than actually taking items, the bailiff usually puts stickers on them indicating that they do not belong to the person any more. Anything needed for daily life cannot be taken. The fendung gives the person time to do what the court has ordered. If the person fails to comply with the court order, the stickered items are forfeited and sold.

Text and photograph of Jacob Wiesenthal copyrighted by Helene Kenvin

A version of this story, written in Yiddish, was published in Sefer Skala (Skala Benevolent Society, New York and Tel Aviv, 1978).

This page created by Max Heffler

Updated Jun 28, 2006. © Copyright 2005 Skala Research Group. All Rights Reserved.