Ottynia

Ottynia

Other Name:

Otyn'a (Ukrainian)

Ottynia is first mentioned in documents from 1610 as a city where Polish aristocrats resided. Jews are known to have lived in Ottynia since 1635, and with about 2000 inhabitants, represented 40% of the population in 1900. It was in the province of Galicia in the Austro-Hungarian Empire until the end of World War I. From 1918 until the outbreak of World War II it was part of Poland. In 1942 the Jewish community of Ottynia was destroyed by the Nazis. At the end of World War II Ottynia became part of the Ukrainian SSR.

Location:

Otyn'a is in the Tlumach district of Ukraine, midway between Ivano-Frankivsk

and Kolomya, at 48.44 N and 24.51 E

Contemporary

Map.

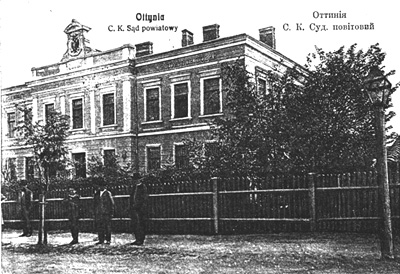

Photo of Ottynia City Court- 1912

Ottynia

Between Two World Wars

1925 Directory

Three

Ethnic Groups Then; Now Only One

First Ottynier Young Men’s Benevolent Association

Photos of Holocaust Memorials

Beth

Moses Cemetery, New York

Holon

Cemetery, Israel

Yad

Vashem, Israel

Szeparowce Forest, Ukraine

Traveling to Otynya

Why

did the Spiegels want to go there?

What did the Spiegels find there?

The

return of Israel Rosenberg

Tips for Travelers

History

The following is a translation by Chana Berman and

Phil Spiegel of the entry on Ottynia in Hebrew from the Pinkas HaKehillot,

Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities - Poland, Volume II Eastern Galicia,

Yad Vashem Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority, Jerusalem 1980.

POPULATION COUNTS

YEAR JEWS

TOTAL POPULATION

1765 296

(?)

1880 1,557

3,714

1900 2,081

4,940

1921 1,728

4,445

1931 1,116

(?)

Ottynia is mentioned in documents from 1610 as a city where aristocrats resided. In a description from 1786 it is emphasized that Ottynia is known in the vicinity as a trade center for salt and tobacco. In the 19th century it emerged as a place for manufacturing clay pottery. At the end of the 19th century or the beginning of the 20th century a factory for producing metals was established and about 500 workers were employed in it. The city was connected to the railway and its station was determined to be a distance of 1.5 km away.

Jews in Ottynia are referred to first in documents from 1635. In the 18th century the Jewish population grew numerous and in 1765 their count reached 345 persons in the city. The rabbi in Ottynia also had authority over 51 Jews in neighboring villages. The rabbi in 1765, Aaron ben Avigdor, extended his patronage also over the Jews of Nadvorno.

The first Jews in Ottynia were engaged in renting property, inn keeping and commerce. In the 19th century, especially toward the last decades, the Jewish community grew rapidly. What caused it was, among other things, that the great rabbi of the Wishnitz dynasty put his base there, a thing that brought additional prosperity from boarding the Hassidim, supplying food and taking them to the train station. Also the founding of a factory for pouring iron developed the trade and increased work for Jewish craftsmen. Rightfully, the local journalist pointed out in "HaMagid" in 1902 that "rich people won't find their place in Ottynia but the poverty that exists in most of Galicia didn't come to us."

In 1899 a Gemillut Hassadim fund was established that gave a lot of help by lending money to merchants and craftsmen. At the beginning of the 20th century an elementary school from the Baron Hirsch Foundation was founded in Ottynia for the Jewish children.

The relative comfort of Ottynia's Jews was terminated with the outbreak of World War I. The Russian conquest (1914-1917) brought with it the destruction of the economy and also harassment of the Jews. Among other things, 405 Jews were arrested, including the city's rabbi, on the pretext that they had sabotaged the telephone line. They were exiled from place to place until they arrived at Buczacz. There they were imprisoned for a few weeks under starvation conditions. When one of them was caught after he succeeded in escaping from the place of quarantine so that he could ask for bread from the local Jews he was punished with 25 to 75 lashes.

As a result of the war the Jewish population of Ottynia decreased and the economic conditions were run down. In 1920 about 1500 people out of 3500 Jewish inhabitants of the city and surrounding villages needed immediate help in food and clothing. About 228 families (786 people) were supported in that year with money from the Joint. Additional damage to the Jewish economy resulted from the removal of the rabbi's court to Stanislawow. As in other cities in the '20's it was difficult for Jews because of taxes. In 1925 the Jewish merchants protested in a strike (they closed their shops for a few hours). A report from Ottynia from 1927 describes the economy of Jews as very depressed. According to that report the majority of Jewish families were really in poverty. In 1928, with the help of the Joint, a credit union was founded for Jewish merchants and craftsmen and a year afterward there was a Gemillut Hassadim fund. But the number of loans and the totals of loan money became smaller from year to year (In 1934 there were 40 loans totaling 3,585 zloties and in 1935 there were 30 loans totaling 2555 zloties). In 1936 the fund stopped working. In 1937 they tried to renew it but it isn't known if the experiment was successful.

The famous Ottynia rabbis (besides Rabbi Aaron ben Rabbi Avigdor referred to above) were: Rabbi Joel Katz who was accepted in 1770 as Rabbi in Stanislawow and on the way to his new office he died; Rabbi Yitzhak Halevi ben Rabbi Meshulam Issachar of the house of Horowitz who acted as rabbi in Ottynia for 50 years in the 19th century. From Ottynia he moved to Zavravno and from 1884 to Stanislawow (He died in 1904). His compositions include "Tol-dot Yitzhak" and "Meah Shearim". His chair in Ottynia was inherited by Rabbi Yitzhak Itsik Taubs and he sat on it 45 years until his death in 1903. In the first decade of the 20th century Rabbi Alter Chaim ben Rabbi Yeshayahu Bierbrauer was the head of the Beth Din in Ottynia. In 1909 he started publication of a literary collection, "Asufat Chochmim" (from sayings in the Bible, Mishnah, Halacha, legends and responsa). Until the First World War (probably from 1910) Rabbi Menachem Mendel Margulius also served in a place nearby or Domatz (?) In 1927 Rabbi Levi Yitzhak Klughaupt was selected rav of the city.

Towards the end of the 19th century Rabbi

Chaim Hager,

the son of Rabbi Baruch Wishnitz made his permanent place in Ottynia and

henceforth he and his descendants were married with the name Admor Ottynia

and their Chassidim -- Chassidai Ottynia. During the First World

War Rabbi Chaim moved to live in Vienna and then settled in Stanislawow

and ruled his court there and also ruled the Admor Ottynia. His Mishna

was printed in a book "Tal Chaim". After his death in 1931 his son

Rabbi Israel Shalom Joseph was crowned with the crown of the Admor in Stanislawow

and he continued in his office until the Holocaust era, where he died.

In Ottynia the one who continued the Admor Ottynia at the end of the First

World War was the other son of Rabbi Chaim, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Hager

(It is not known if his permanent place was in Ottynia).

The Zionist circles were organized in Ottynia in the last years of the 19th century. In 1899 the local association, "Zion", hosted a Chanukah party and about 300 people participated. At the same time a school was erected by the Baron Hirsch Foundation. After a while a Hebrew school was opened. In 1906 about sixty students, mostly girls, studied in it.

A testimony of the influence of Zionists in Ottynia at that time will be the fact that in this Chassidic city in 1905 112 shekels were sold and in 1906 there was a memorial to Theodore Herzl in the synagogue. In 1911 the existence of a Mizrahi branch in the place was made known.

The Zionist activity in Ottynia was renewed at the end of World War I and branches of the Zionist organization (General Zionists, Mizrahi, Union and Revisionists) and nests of youth organizations (Young Zionists, Betar, HaShachar, Achuva, Akiva, and Gordonia) were thought to be active in the area. A "helping" branch was founded in 1923 and a branch of the Pioneers was established in 1924. A branch of WIZO that was founded in 1936 was active in addition to cultural and informational activity in the areas of education and social help. WIZO organized classes for knitting and care was provided to the sick and aid in the form of food and clothing went to the needy of the area. In the '30's a supplementary Hebrew school that was connected to the school network of "culture" existed in Ottynia.

In elections to the Zionist Congress of 1935 the votes of the shekel purchasers of Ottynia were as follows: General Zionists - 261 votes, Mizrahi - 57, Eretz Israel Labor List - 188, State Party - 77 and HaShahar - 60 votes.

There was a majority of Zionists in council of the congregation of that period. In 1927 five Zionists, one representative of Yad Harutsim and two unaffiliated members were chosen for the committee. In 1933 the Zionists again were the majority in the congregational council, and through the influence of the local rabbi a Zionist was chosen to be chairman of the council.

In 1933 four Jews, most of them Zionists, were chosen out of a total of 12 to the town council. A number of Jewish youth in Ottynia were active in the Communist party or illegal groups adjacent to it. In 1936 Isaac Schechter, the son of the ritual slaughterer in Ottynia, was brought to trial and accused of communist activity. In 1937 a Jew from Ottynia was tried because he collected money for the sake of the Spanish Republic. Because of communist activity a Jewish girl from Ottynia was brought to trial in 1938.

In the '30's expressions of anti-Semitism increased in Ottynia. Among others there were instances of firing Jews from their positions (In 1933 Jewish employees of the cinema were fired), of propaganda (distribution of proclamations and calls to boycott the Jewish businesses) and also of breaking windows in Jewish houses and hitting Jews. In 1934 many windows were broken in the houses of many Jews including the home of the rabbi who had a heart attack because of the excitement.

We are missing information on the fate of the Jews in Ottynia during the period of Soviet rule (September, 1939 to June, 1941). Also the information on the life of this Jewish population during the Nazi occupation is weak and contradictory. In August, 1941 bloody pogroms occurred in Ottynia - the handwork of the Germans and the local Ukrainian people. The pogroms lasted for a few days and large number of Jews were murdered. There is also no knowledge of the conditions of Jews in Ottynia during the period from August, 1941 to September, 1942.

But nevertheless, we know that on the eve of Succoth 5703 (September 25, 1942) the Jewish population was annihilated. Gestapo troops came into Ottynia. German and Ukrainian policemen surrounded the city and put machine guns at the street corners. They passed from house to house, concentrated all the Jews and put them on trucks. According to one version, they were transported to an unknown place and only a small group of escapees arrived the next day (September 26, 1942) in Stanislawow.

According to other information all the Jews of Ottynia were sent out - about 1800 in those days - in that "Aktion" (deportation) to Stanislawow. At the camp station they were shot on the spot or transported to the Belzec extermination camp.

Life in Ottynia by Norman Latner

In the town of Ottynia in the province of Galicia of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Hersch Kletter who was born in 1869, lived with his wife Minnie and their children, in a small house that had no water well, and certainly no bathroom. Yakob, their German neighbor across the road, was kind enough to let them use his well.

The center of activity in the house was the "big room" - a combination kitchen, living room, dining room, bathing room and bedroom for all but the parents, who slept in a small room off to the side. Dominating the room was the black iron stove used for cooking, baking and heating. There was a second small room and a large root cellar under the house where the vegetables were stored. And like most poor people, everyone slept on straw mattresses.

Squeezed into the little house were the 4 girls, Shaindel, Molly, Rose and Anna, and the boys, Abe and Nathan- and at times, Lou, the child of Hersh's first marriage to Surah Gold. Surah died while giving birth to their stillborn second child when Lou was two. But mostly, Lou lived at his grandfather's home about 3 houses away. His grandfather, Chuna Gold, owned a farm with a cow and a horse, and had a larger house than the Kletters. He even ran a small store in town.

The Kletters were not as well off. Sadly, their 2 year old daughter Chanakele had died of malnutrition. They planted some vegetables, mostly potatoes, in their little yard and kept a few chickens. Hersch made a meager living as a Schochet (kosher slaughterer) and by reselling an occasional lamb or other animal, and he could also ``daven for the omed'' (pray for the congregation) in the shul (synagogue). This, of course, was an honor but didn't put bread on the table.

Jews had lived in Poland since the Polish Kings - Boleslav V in 1264 and Casmir the Great in 1364 - invited the Jews of Germany and Central Europe to the impoverished peasant land. They recognized the value of the Jews in business, commerce and medicine and for the badly needed skills they could bring to Poland.

When the first census was taken in 1765, Polish Jews made up 10 percent of the population, practicing all trades and prominent in many aspects of urban life. From the 16th century until the Holocaust, Poland was the world's chief center of Judaism.

Poland, located in the middle of Europe, changed ownership many times with the winds of war, and of course, Ottynia with it. Before WWI, Ottynia was part of Austria-Hungary, but in 1918, it again became part of Poland. The town of Ottynia, located near the Carpathian Mountain region, along the banks of the Dniester River, was in 1945, swallowed up by the Soviet Union as part of the westward expansion of the Ukrainian SSR. Today, not one Jew can be found in Ottynia.

But between the late 1700's, and the early 1940's, the Kletters were there, and many others like them. Ottynia was a town of 1,000-2,000 people, located on a road between Kolomyja on the south and Stanislawow on the north. Stanislawow, (28,000 inhabitants and 56% Jewish) thought of by most Ottynia folk as ``the City'', was about 4 km away - 1/2 hour by train. Further north was the larger city of Lvov (sometimes known as Lemberg) with 220,000 people, 35% Jewish. Tarnapol, and Tarnow, known for clothing manufacturing, were also in the region. Closer in, were the little towns of Korezow and Chryplin. You won't find Ottynia on a typical map - only the most detailed of Polish maps will show it, located at 49 deg latitude, which puts it about as far north as Winnipeg, Canada. Winters there were quite cold and the summers were hot.

Actually, the Kletters lived in Mickelsdorf, a suburb of Ottynia, about 1-km away and the home of a few hundred families, only a few of which were Jewish. The rest were mostly Germans, some quite wealthy. The price of a modest house in those days was about $200.

Mickelsdorf had no synagogue and no stores until a man named Ben Tzion opened a Grocery. Things are relative, and so the people in Mickelsdorf thought of Ottynia as ``the City''. Sam Latner, the son of Itchia the shoemaker, also lived in Mickelsdorf. In 1910, as a boy, Sam saw Kaiser Franz Josef passing through Ottynia with a regiment of Austrian troops. (Before WWI, all Austrian soldiers were required to wear mustaches.) Later, in 1917, he saw the Tsar Nicholai come through the town. Around 1920, his mother, Bela Latner (nee Forsetzer) and Minnie Kletter arranged a "shiddach'' (match) for their children Sam and Shaindel (Jennie). More than seven years were to pass before Sam could follow Jennie to America and marry her. Several of those years were spent in the Polish Army and a few more waiting, before he was allowed to sail to America on the SS Leviathan.

The town of Ottynia, being located along the Dniester River, was an ideal location for manufacturing, and starting before WWI become the site of a large industrial complex that had an iron factory, a lumber sawmill, a flour mill, a blacksmith shop and for a time, a brewery. The site was about 20 blocks long on each side, with railroad tracks allowing trains to unload raw materials and send out finished products.

The factories were lit by electric lights, quite amazing and modern at this time, and the machines were powered by steam. Most of the fuel for the steam boilers was the sawdust and waste generated by the sawmill.

At one time as many as 3,000 people worked at these factories. However, few Jews were hired at the Iron Foundry, and only 6 or 7 at the Sawmill. Moishe Kletter, a distant cousin, worked in the sawmill as a skilled carpenter. His brother Max Kletter was later to become a well-known singer and Jewish stage star in America. Sam Latner also had a job at the sawmill, as a helper making parts to maintain the machinery. He and Moishe often ate lunch together.

The sawmill had 6 giant saws to cut the largest logs into boards, as well as many smaller saws for other jobs. Their blades had to be sharpened twice a day, and Sam was one of the men who did this job. The iron works was at one time a major producer of farm equipment. The brewery made both wine and beer. The wealthy owner of these vast holdings was a German called Mr. Brett. Before WWI, he drove the first motor car ever seen in this area. Then WWI came and left - and with it the vast factories of Mr. Brett. All was destroyed or dismantled. Only the sawmill would be rebuilt, and Sam Latner would again have a job that paid him a few zlote a week.

For those Jewish girls who were able to go to school, there was the Polish School for girls which Shaindel attended, or the German School which Rosie, Anna and Molly attended. Some boys also went to the German School, as did Abe Kletter. But if you were a Jewish boy and really lucky, then you probably went to the Baron Hirsch School- one of many scattered throughout Poland and Galicia, and founded and supported by the French nobleman Baron Hirsch. The children had to walk several miles each day to get there. Along with the instruction and books they received, they were also given shoes and warm winter clothing. Nathan Kletter got his first pair of shoes there. Lou Gold went to this school and studied carpentry. Six years of school was the limit, and then at about 13 or so, you were sent out to work. When Sam Latner graduated, he went to work in a clothing store where he returned stock to the shelves, brushed clothing and swept the floors. His brother, Yosha, 13 years younger was apprenticed to a tailor in the town of Sniatyn, southeast of Kolomyja.

There were no higher schools in Ottynia. You had to travel to Stanislawow for the gymnasium, the equivalent of our high school. Very few managed to go. But before school started and after school ended, there were many hours of Cheder, making a long day much longer. Hebrew reading and writing, Talmud, Gemora and Rashi were just a few of the things that had to be mastered. And when it came time for your Bar Mitzvah, your father took you to Shul on a Thursday morning, you got an Aliaya and read the Haftorah. The men drank a glass of schnapps and that was that.

Ottynia had many stores- in fact almost every building had some kind of store. New and used clothing stores, food stores, liquor stores, hat stores, shoe stores and general merchandise stores to name a few. Doctors, mostly Jewish, were there. There was a City Hall, a Lower Court which met regularly, and a Police Station with a few Polish Policemen. One day in the early 1920's one of these Poles stopped Willie Kletter, who was walking with Sam Latner, to demand if they knew the whereabouts of one Abraham Kletter who was wanted by the Army. They told him it was too late, Abe was already in America!

Tuesday was market day, and people came from all around, by horse or by foot, and set up booths or sold their wares from the back of a wagon. Anything and everything was for sale- suits, pots and pans, pigs, chickens, fruits and vegetables and such.

Ottynia even had a theater that showed films and sometimes stage plays when traveling actors came to town. But the thing that Ottynia was most known for, was the Great Salash Synagogue and the revered and famous Reb Chaim Hagar who was its rabbi. Amazingly, this giant brick Shul could seat 5000 people and was really three Shuls in one. The Largest was used only on Saturdays and holidays while the others were for weekdays and evenings. On cold winter days, you sat in your coat since there was no heat, but still students came from far and wide to study with Reb Chaim. The Gabbai of the Shul was Itchia Latner the shoemaker. But all things come and go, and so it was with the Great Shul, which closed its doors near the end of WWI in 1917, and the Rabbi and his family moved away to Stanislawow.

Itchia, and his son Sam were to see the revered Rabbi one last time, in 1927, when they came to Stanislawow before Sam left for America. Reb Chaim exhorted Sam to be a good Jew and bestowed his blessing on him. Sam never forgot.

The Kletters didn't go to the big shul, but to the closer of the two smaller ones in Ottynia. The shul was actually a room off to the side of Velvel's Shenk (tavern), which contained some benches and a small Torah Ark.

Life was not easy for the Kletters, especially after Hersch, with his son Lou Gold, left for America in 1913 with the idea of saving enough money to bring his family over. There was a particularly bad time during WWI when the family lost contact with Hirsch. Cossacks roamed the countryside, and one night decended upon the Kletter house. Minnie had already hidden Schaindel beneath the flooring. Luck was with them. The Cossacks looked at the sleeping children- and left. And how fortunate they were to have Yakob as their neighbor. What would they have done without him. The children all called him uncle, and he visited every night bringing apples and flour. It was he who lent Hersch the 36 dollars that an immigrant needed to show in order to enter the United States. When Hersch was finally able to send the money back, Yakob refused to take it and gave it to Minnie instead.

By three in the morning, Minnie Kletter was already up and doing the baking. The wonderful aroma of the challah or cornbread in the oven was enough to wake up some of the children. The bread that was baked on Friday usually ran out by Tuesday.

Along with going to school, there were chores to do. Shaindel went to the market every day, while Rosie, starting at age 10, helped her mother with the cooking. Minnie cooked vegetables of all kinds and much kasha, a staple of their diet. Minnie also milked the Kletter cow each morning and then sold the milk in Ottynia. But there was none to spare for the children. Another chore for Minnie was to make the girls dresses which she sewed from potato sack cloth. And there was still more to do. Minnie worked in the grain fields cutting and bundling wheat. For every 13 bundles she collected, she got one for herself. Nathan often helped her, while Shaindel took their share to the mill in Ottynia for grinding. And once a year, Shaindel, who would be known as Jennie in America, baked the Passover Matzoh. She always had to hide it in the attic to keep the younger children from eating it before the Seder.

Shoes were hard to come by in the Kletter family.

Only Shaindel and Nathan each had a pair for school. Rosie was forever

hoping that somehow shoes would magically appear for her. She even

made Shaindel carry around a string with her foot size. Rosie was

a spirited girl who also managed to learn to read and write with the help

of an "ABC" book that someone gave her.

There came another bad time when all the family

was struck by Typhoid fever. It was Minnie's brother, Willie Kletter who

took care of them all. With Hersch gone, Uncle Willie was like a father

to the kids. He was a tall man who had red hair just like one of

his sisters, who was called "Red Mollie". Willie, who everyone said

was a "very good person", was married to Malka and had a young daughter.

It was Willie who would later inherit Minnie and Hersch Kletter's house

when she and the children left for America.

Yet for all his goodness and generosity, fate was unkind to Willie. In 1922, three days before Pesach, he returned home to find thieves leaving his house with his bedding and other posessions. He followed them to a flea market, and when he confronted them, they shot and killed him. Willie Kletter------- "a very good person"----dead at 27.

Hersch was not the first Kletter to venture forth to America in search of a better life. It was Minnie's unmarried sister Lena, or Letchia as she was often called, who holds that record, for she arrived in 1902. Three years later, in 1905, two of Minnie's other sisters, Fanny and Rose came to America. In a strange twist of fate, these attractive sisters would then meet and marry two brothers, both named Louis Jacobs. The younger brother, who had studied to be a Rabbi, stole his brother's steamship ticket and name and came to America, where he joined the US Cavalry. He and Fannie later settled in Ohio. The older brother eventually made his way over, and after marrying Rose, made his home in California. In 1913, when Hersch left, so did Minnie's sister "Red Mollie", who would marry Morris Litt, an electrician usually known as "Litvak".

But not everyone who came to America was happy here. The streets were not paved with gold. Earning a few dollars was a struggle and living conditions were harsh, with many people crowded into a few tenement rooms. Some longed for the old Shetl. And so there were those that returned to Ottynia. Beryl Kletter, a distant relative was one, and so was Minnie's sister Lena, who in 1910, after 8 years in America went back. It was there she married the widower Moishe Forsetzer and had five children, and two of them eventually made it to America. Kopel, sometimes known as Karl Frost, arrived in 1935. His brother Willie, amazingly survived WWII and then managed to make his way to the States.

Between 1913 and 1921, Hersch sent whatever little cash he could, whenever he could. He persevered, and by 1920, Nathan and Jennie came to America. And a year later, Sam Latner helped them pack and the remainder of the Kletters left Ottynia. (It was Sam's father who later sold the Kletter house and sent the $200 to Hersch.) They traveled by way of Warsaw, where they stayed for a time at a house at 39 Nalyska street and were helped by the HIAS. On November 14, 1921, the Kletters arrived in the United States.

Today in Ukraine, there still is a town called Ottynia, but it is not the Ottynia of the Kletters. All traces of a Jewish presence are gone. There are no Shuls, no Cheder, no Hebrew texts and no chulent warming on the stove. No one calls out for Nissen or Shaindel or Yosha. All that remains of the Ottynia of the past, a place of hardship and a place of joy, lives on in the hearts and the memory of the few survivors - and in us, and our children if we too try to preserve these memories of the past.

---- (With deep appreciation and gratitude, I would like to thank Anna Schreier and especially Sam Latner for the time and effort they spent in supplying so much of the information about life in Ottynia.)

Ottynia city court depicted on a postcard in 1912.

Views of Ottynia Between the Two World Wars

Jan Boczar was born in Ottynia in 1920.  At

the end of World War II all the ethnically

Polish residents of Ottynia and throughout the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist

Republic were forced to move to Poland. At the same time ethnic Germans

moved from western Poland to East Germany and ethnic Ukrainians from Poland

moved to Ukraine. Jan Boczar was part of this migration. He

is a retired economist residing in Opole, Poland and writing a book in

Polish about the history of Ottynia. He provided this photo of Market

Day in Ottynia taken "some time between the two world wars".

At

the end of World War II all the ethnically

Polish residents of Ottynia and throughout the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist

Republic were forced to move to Poland. At the same time ethnic Germans

moved from western Poland to East Germany and ethnic Ukrainians from Poland

moved to Ukraine. Jan Boczar was part of this migration. He

is a retired economist residing in Opole, Poland and writing a book in

Polish about the history of Ottynia. He provided this photo of Market

Day in Ottynia taken "some time between the two world wars".

In 1925 a directory of cities in Poland was published in Polish and French. It described Ottynia as: “A small city (including the suburbs: Markow, Gaj, Mikulsdorf, Za Grobia) in the district of Tlumach. It is the seat of the tribunal of Stanislawow. There are 4455 inhabitants. It is 1 km from the Kolomyja-Stanislawow railway line. It has a municipal office building, (Roman) Catholic and Greek Catholic churches, trade associations of merchants, industrialists and tavern keepers. Market day is Tuesday. There are fairs 13 times each year for sale of cattle and hogs. There are brick factories and oil refineries.”

The mayor was Jozef Papst.

The professionals and tradesmen listed were:

Physicians: Dr. Maur. Spindel and Dr. Ar. Vogel

Dentists: Joz. Bartfeld

Veterinarians: Deresz Mikolaj

Lawyers: Dr. Drohomirecki, Dr. Joz. Fullenbaum, Dr. Fryd Krasucki

Notaries: Aleks Strocki

Midwives: M. Bodnar, F. Jarocka, G. Reichman

Pharmacists: G. Schiffer

Tinsmiths: J. Engelsztejn, J. Kanzenpold, Koch

Fabrics: R. Dienes, H. Heiferman, I. Kerzner, A. Kramer,

P. Kramer, B. Lichtman,

A. Majbach, Margulies, I. Preminger, S. Rinzler, S. Schorr, I. Seinfeld,

M. Seinfeld,

R. Stepper, F. Udelsman, N. Udelsman, S. Wolin

Cattle Merchants: I. Bodnar, J. Kanter, G. Fursetzer, M. Fursetzer, I. Gebuhrer, Schmerler

Brick factories: J. Papst, J. Udelsman

Tile works: I. Gebuhrer

Dry Chemicals: M. Schiffer

Hairdressers: M. Weintraub, Ch. Zimmerman, M. Zimmerman

Haberdashers: M. Fach, S. Fischer

Eggs: Z. Koch, S. Scheuer, M. Weisberg

Savings & Loans: Kasa Stefczyka

Wheelwrights: F. Pendel, A. Werstler

Chimney-sweeps: F. Bakaj

Ready-made clothes: S. Grunwerk, J. Grenberg, M. Holder, D. Kriegel

Horse merchants: L. Hutt, I. Bodnar

Blacksmiths: J. Ernst, M. Pendel, Adam Werstler

Tailors: I. Bruch, B. Friedman, Ch. Gleiss, J. Keller, S. Rinzler,

J. Rozenstrauss,

H. Rumel, M. Rumel, H. Steinhorn

Cooking implements: H. Bitman, S. Kupferman, Ch. Rand, W. Rand

Flour: Prowizor, Salamon Schaenter, Samson Schaenter

Creameries: M. Kurz, J. Sbirczak, B. Uhrman

Mills: Bela Rubinstein

Dairymen: J. Rechtschaffer

Petroleum: S. Kramer, E. Nebenschoss

Fertilizer: A. Dulberg

Hunters: B. Dulberg, M. Grun, F. Grunberg. S. Kramer, S. Rinzler,

A. Schreier,

P. Schreier

Oil: B. Baran, M. Feuer, L. Fursetzer, K. Kratenstein, J. Majbach

Fuel: S. Frohlich

Bakers: A. Mortmana, H. Watenberg

Rope makers: L. Kwartler

Restaurants: Ch. Kleinberg

Sundries: G. Aron, J. Bartfeld, B. Bretholz, H. Buchwalter, A.

Dreier, Ch. Dulberg, M. Feuer, J. Fircher, J. Geisler,

M. Grabszeid, M. Hass, J. Heger, D. Hochman, Hoffman, Kaufer, P. Kindler,

M. Klarreich, Roznicze Kolko, S. Kramer,

B. Krauschar, Men. Kramer, Moz Kramer, E. Kreisler, M. Krems, F. Krum,

S. Lautman, S. Loscher, J. Marmarosz,

F. Mausner, B. Mortman, E. Nebenschoss, J. Rand, I. Ruder, Ch. Sager,

F. Sager, “Samopomoszcz”, M. Scheur,

S. Schlosser, B. Spinner, Ch. Spiegel, M. Stengel, M. Streit, Sz. Tanenzapf,

G. Turkeltaub, K. Udelsman, M. Udelsman,

Ch, Weisberst, G. Weisberst, J. Werth, M. Ziering, “Jednosc”, W. Lasek,

H. Silberman

Saddlers: J. Werstler

Butchers: H. Braunstein, N. Bruch, M. Hryhorow, M. Hutt, L. Zankier

Leather goods: S. Bernstein, B. Dulberg, A. Schreier, S. Tager, J.Wechter

Carpenters: E. Bergenfeld, R. Burghardt, A. Kletter, Ch. Schrier, J. Soffer

Shoemakers: W. Fuhr, M. Kletter, F. Konarski, J. Kupczak, M.

Lindauer,

M. Zworn

Sawmills: Bcia Rubinstein

Tobacco: H. Kurys, W. Tyszkiewiczowa, J. Slobodrion

Pork butchers: M. Czarnocki, J. Leszczynski, Sz. Szwedon

Sparkling water: D. Holder, I. Kern, M. Singer

Sparkling water manufacturing: W. Singer

Wholesale liquor: P. Schreier, A. Schorr

Liquor: M. Baron, L. Dankner, Ch. Haber, L. Lakritz, W. Prowizor,

A. Schachter,

A. Schorr, P. Schreier, S. Sokal, A. Stempurski

Grains: J. & Ska. Buchsenbaum, Kramer, Rinzler, S. Schachter,

M. Udelsman &

M. Dulberg

Clock makers: B. Honig, Sz. Kremer, L. Schleifer

Hardware: S. Hundert, S. Kerzner, I. Loscher, S. Loscher, M.

Mausmer, J. Pecher

Three Ethnic Groups Then; Now Only One

Census figures for the year 1935 show that Ottynia had 4,355 inhabitants of whom 1,631 were Greek Catholic (ethnically Ukrainian), 1,512 were Roman Catholic (ethnically Polish) and 1,212 were Jewish. So it could be said that before the outbreak of World War II, Ottynia was roughly one-third Ukrainian, one-third Polish and one-third Jewish. As we know, the Jewish inhabitants of the town were annihilated by the Nazis. What is not so well known in America is the fact that at the end of World War II the entire Polish population of Ottynia left the city.

At the Yalta Conference in 1945 Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt designed

new boundaries for central Europe. Poland lost a third of its pre-war

area. Ottynia and much of Galicia was part of the area of Poland

that was given to the Soviet Union and became part of the Ukrainian S.S.R.

As "compensation" Poland was given a large part of Germany east of the

Oder and Niesse rivers. This part of western Poland includes the

provinces of East Prussia, Pomerania and Silesia. In 1945 over 1,000

Polish refugees from Ottynia who wanted to avoid Soviet rule migrated to

western Poland. The German polulation of these provinces was expelled

to East Germany. To complete the ethnic realignment, some Ukrainians

who were living in Poland moved to the Soviet Union.

First Ottynier Young Men’s Benevolent Association

This landsmanschaft was founded in New York in 1900 and organized the Ottynier Relief in 1914 which was active until 1950. Members of the Ottynier Young Ladies andYoung Men’s Progressive Association were incorporated into the society in 1929. The First Ottynier Ladies Aid Society was organized in 1939.

The YIVO Landsmanshaftn Archive contains minutes from 1946 to 1967, correspondence and bulletins and a short history of the society. RG1036 is the portfolio number.

The current president of the First Ottynier Young Men's Benevolent Association is Henri Zimmerman, 1118 Haral Place, Cherry Hill, NJ 08034.

The following is an essay on the organization written in 1993 by Norman and Herbert Latner. Both of them are members and Herbert Latner is Vice President.

When our parents and grandparents came

to America, they did what so

many thousands like them did -- they organized or joined a fraternal

lodge of

"landsman" who came from the same home town. The lodge that most of

the

Kletters joined was The First Ottynia Young Men's Benevolent Society.

Note

the "Young Men " in the title to distinguish it from the earlier society,

the

Dorshe Tov Ottynia, whose members were no longer so young. This

older

Society was already on its last legs in the 1920's when so many of

the new

Kletters settled here. Hersch Kletter (Grandpa) who arrived in 1913,

was a

member of the Dorshe Tov Ottynia, along with some of the older Forsetzers,

Feures and Knishbachers.

The Society served several important functions.

First, and perhaps

foremost, it helped bridge the gap between "Di alte heim" (the

old country),

and the new, and aided the newly arrived "greenhorns" in adjusting

to the

different customs and life-styles of America. In more tangible ways,

it assisted

in jobs, medical care, finding places to live (often as boarders at

first), and other

services. There were even several physicians who had ties with Ottynia

and

were the "official" doctors of the Society. They often accepted

lower fees from

members for their services, and for many years, performed the

constitutional

requirement of the mandatory physical for candidates and their wives.

Dr.

Herman Blond of First Ave. was one that some of us remember.

And there

were still other benefits, such as a burial plot and a modest burial

cost payment.

The Society made donations to needy individuals, both in and out of

its

membership, and sent money to aid those still living in Ottynia, and

in later

years, in Israel.

One of the most important functions of the

lodge was social -- and in fact,

the constitution even specifies a four member entertainment committee.

The

frequent meetings, once every two weeks with refreshments served, and

other

gatherings throughout the year provided the members with an opportunity

to

socialize with their childhood friends, to speak in the comfortable

and expressive

Jewish language, and to reminisce about the good old days in Ottynia.

On the

occasion of the marriage of any member in good standing, a gift of

$10 would

be presented, and $5 would be given for the wedding of a daughter or

the Bar

Mitzvah of a son.

Naturally, the Kletters were involved. One

of the most active and

prominent officers has been Karl Forseter, also known as Forsetzer

in Europe

and Frost in his business, but probably best known affectionately as

just Kopel.

Kopel served as president and in other board functions for many years

as did his

brother Willie. Abe and Nathan Kletter were also active members who

attended

meetings regularly. In earlier years, Grandma Minnie's brother,

Morris Kletter

who owned a cigar store at Columbus Circle in Manhattan, was an influential

officer. In recent years, Sam Latner has been a faithful trustee,

while Herb

Latner is currently an officer, serving with our genial President,

Israel Rosenberg

and Ex-president, the charming Frieda Schmerler.

The destruction of the Jews of Ottynia in the

Holocaust, together with the

selectively restrictive immigration policies of this country and the

natural aging

of the membership, has caused a severe decline in the organization.

As a result,

attendance at meetings and other functions has been steadily declining,

and this

once active and vibrant organization which used to hold meetings every

two

weeks, has been reduced to having two meetings a year, one of these

being the

spring luncheon. It has been difficult to get the children and grandchildren

of the

original members to join and carry on the work of the society. To a

great extent,

this is because the original needs and goals have no meaning

to them, and no

effective enticements or ways to restructure the organization have

been found

that could attract the present generation.

Could the founder and driving force behind

this society, have guessed the

state of affairs that would exist some 93 years later? Who knows!

But what we

do know is that on the Saturday night of May 12, 1900, at the home

of the

Reverend Joseph Kramer, a dynamic young man with great foresight

named

Adolph Arbeit, called together 13 "landsman," and organized The

First

Ottynia Young Mens Benevolent Society. Time has not erased the names

of

these men - Adolph and Herman Arbeit, Jacob Altman, George and Isaac

Haber, Lou Bader, Phillip Hutt, Moses and Max Kramer, Kopel and Abe

Rauch,

Sam and Max Rinzler and Sigmund Shatzberg.

It is interesting to examine the constitution

of the Ottynia Society as a

means of understanding the thinking of the founding fathers.

In the very first

article, they look ahead some 90 to 100 years and address the issue

of

disbanding the Society. I quote: "Sec.2- The Association shall

never be

dissolved, nor the name changed as long as there remain 7 members who

wish

to continue it."

Section 3 states the object of the association

to be as follows:

A- To aid its members in case of sickness or need. B- To help

one another in

every possible way. C- To have social and cultural gatherings. D- To

maintain

true friendship among the members. and E- Burial of members and

their next of

kin as hereinafter provided. ----These benevolent and noble thoughts

serve as

well today as they did 100 years ago.

At the turn of the century in 1900, Ottynia

was a small quiet town in

Galicia, Austria-Hungary. It was located on the Czernowitz Railway

between

Stanislau and Kolomea. According to an 1890 atlas, the

total population was

4117, of which about 2000 were Jewish, if you include the small villages

around

Ottynia. Many young Jewish men of Ottynia were not satisfied to remain

in a

small town and started emigrating to the United States about 1890.

And in America, the "Ottynia" society grew

with the years. The

membership was young, had much in common, and worked hard for the success

of the organization. Immigration from 1900 to 1914 was not restricted

by

quotas and as "landsleit" arrived here, they were welcomed into the

Association.

At the outbreak of WWI, all immigration

stopped and the United

Ottynia Relief Committee was organized by the several Ottynia groups

in New

York City. Collections were quickly started, and by the end of the

war in 1918,

the then vast sum of $12,000 was available to aid our relatives abroad.

A

committee, which included two of our members, Israel Bader and Jacob

Dulberg, went to Ottynia to distribute this money. Thus was started

the

humanitarian relief for our unfortunate brethren abroad, which continued

through

the years until 1950 when all communication with Ottynia was severed.

In April 1929, under the leadership of the

then president, Charles Hutt, the

society initiated 35 members of the Ottynia Young Ladies & Young

Mens

Progressive Association into our organization. These young new

members

revitalized the society and soon many of them held office. They brought

with

them new ideas. The Loan Fund books were modernized and the account

books

were rewritten using a new bookkeeping system. Notices of meetings

that were

sent to members were now in English. The Ottynia Bulletin, published

for so

many years, was a result of their work. This group also brought

with them the

plots on Baron Hirsch Cemetery.

To expand its benevolent work, the First

Ottynia Ladies Aid Society

was organized in 1938 and has been active in Hadassah and other causes.

At the outbreak of WWII, all immigration stopped

again. Most of the

young members and sons of members were called into the Armed Forces.

A

Service Men's Committee was organized, which raised money and sent

packages

to the 135 Servicemen involved, some of whom never returned from the

war.

On April 15,1944, The United Ottynia Relief

Committee was

reorganized, and a Victory Fund Drive was started which raised $22,000

for our

landsleit in Ottynia. Interestingly, Ben Gold #1, was Chairman and

Ben Gold #2

was secretary. Karl Forseter also served on this committee. When

the war in

Europe ended in 1945, word came from the survivors of Ottynia, and

money,

food and clothing were sent to them at once. Out of a Jewish population

of

about 1800, our organization was able to locate 390 survivors. Many

of them

were helped to emigrate to this country and to Israel. This committee

worked

closely with HIAS and the Joint Distribution Committee, and the name

"Ottynier" became known in all the refugee centers in Europe. The aid

given to

these survivors often gave them the courage to live until they could

leave the

camps.

During the early part of WWII, from September

1939 to June 1941,

Ottynia was occupied by the Russians, and little is known about that

period.

And then the Nazis took over, and the Jewish annihilation began in

earnest.

Two stories have emerged which share

a number of similarities and some

significant differences. Ben Gold #2, reported the following in 1967.

"From correspondence with the survivors, the

committee learned that the

Jewish inhabitants of Ottynia had been taken by truck, in two groups,

towards

Tolmitch, where a mass grave had been prepared. They were then

shot and

buried at the spot on that day of October 5, 1941, the first day of

Succoth. The

only survivors were those taken into the Russian Army, and the young

people

that fled into the woods where they lived for over two years

until the Russian

Army drove the Nazis from Ottynia."

Philip Spiegel, the son of a past society president,

found the second

version in "The Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities- Poland, Vol. II",

and has

translated a portion from the Hebrew. He states that in August

1941, during the

Nazi occupation, bloody pogroms occurred in Ottynia - carried out by

the local

Ukrainians and the Germans. Although they lasted only a few days, a

large

number of Jews were murdered. There exists no knowledge of the plight

of the

Jews of Ottynia from August 1941 until September 1942. But on the eve

of

Succoth, September 25, 1942, Gestapo troops came into Ottynia.

German and

Ukrainian policemen surrounded the city and set up machine guns at

street

corners. Then they went from house to house, rounding up the Jews and

putting

them on trucks. At this point, either most were killed at an unknown

place and

the remainder temporarily taken to Stanislav, or they were taken to

the Belzec

extermination camp. In any event, what is clear is that the Jews

of Ottynia,

about 1800 souls, were totally annihilated.

To perpetuate the memory of the Jews of Ottynia

who perished in those

nightmare times, the Society erected a memorial monument at its Long

Island

cemetery some years ago. A small group of members, led by Kopel

Forzetzer,

makes an annual pilgrimage there.

Click here to see photos of the monument at Beth Moses Cemetery.

At the end of the war, a few survivors drifted

back to Ottynia, where they

found themselves quite unwelcome by the new owners, the gentile peasants

who

had long ago taken their homes and property. The Jewish presence

was gone

forever from the town of Ottynia, and little remained to show that

it had ever

been there. Even the cemetery had been destroyed.

In 1967, when Ben Gold #2 was President and

wrote a short history of the

society, he estimated that, of the survivors, there were about 250

living in Israel

and 100 in America. Many more, he felt, were still in Russia

and other parts of

the world.

Today, there are perhaps 150 names left on

the membership rolls of the

society. Many are widows and still more live in Florida and some are

in Israel.

But, there are still at least 7 members who appear at meetings, and

so the

organization goes on a little longer.

The Ottynia Society is now some 93 years old,

and like an elderly Jewish

gentleman, has lost the vigor of it's youth. But this elderly

gentleman, who now

walks slowly and wears an out-of style suit, has much to be proud of

-- a

lifetime of good deeds, of charity and helping the needy, of camaraderie

and

friendship. While the future may be uncertain, the accomplishments

of the

First Ottynia Young Mens Society stand as a monument to its glorious

past.

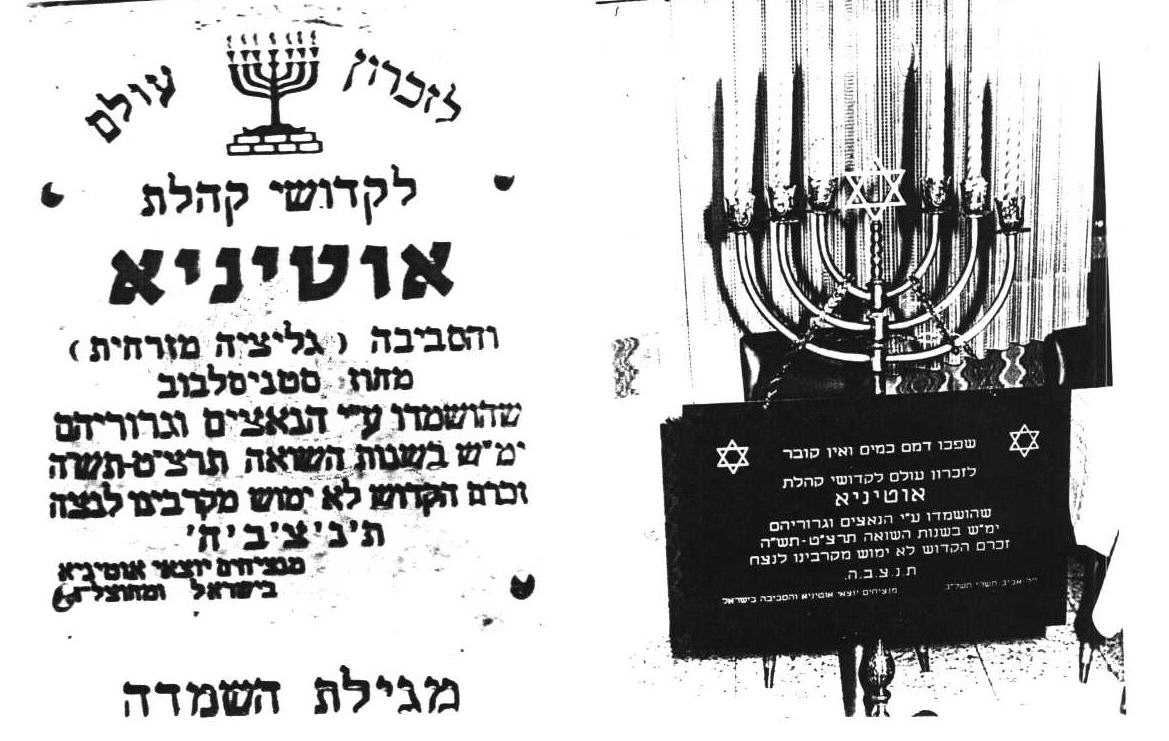

Memorial to Holocaust Victims

of Ottynia at Beth Moses Cemetery,

Farmingdale, New York

The Hebrew inscription at the top of the monument can be translated as “They poured their blood like water and there was no one to bury them.”

The families from Ottynia who perished in the Holocaust and whose names

are inscribed on the monument are:

| Abzug | Fortsetzer | Kramer | Schmerler |

| Shulim, Pesia | Moses, Lina, Klara, Max | Moshe, Hinda | Moses, Klara |

| Bardfeld | Gleiss | Kriegel | Schreier |

| Jacob, Reisel | Chaskel, Chacie | Mayer, Regina | Pinkas, Amalia |

| Blond | Grinberg | Kriegel | Schreier |

| Benjamin, Eda, Sylvia | Icyk, Soni | Abraham, Feige | Pinchas, Cipra |

| Bruch | Holder | Kriegel | Schreier |

| Israel-David, Chana | Meyer, Pesia, Branah,

Chaya, Mina |

Chaim, Mincia | Chaim, Hudia |

| Bruch | Hutt | Latner | Soffer |

| Israel-Itzik, Ruchel | Hersch, Joncie | Isaac, Bella | Anskel-David, Brancie |

| Dulberg | Kanter | Lempel | Sperber |

| Berish, Malcie | Shloime, Bertha | Israel, Miriam, Abraham | Regina, Theresa, Pola |

| Dulberg | Kanter | Mahler | Steinhart |

| Motie, Rivka | Joachim, Golde | Motel, Kreinci | Chaim, Sarah |

| Dulberg | Keller | Popik | Tauber |

| Samuel, Klara, David | Jacob, Cillia | Samuel, Clara, Solomon | Joseph, Rose |

| Eisenstein | Keshner | Rand | Teitelbaum |

| Mayer, Leah | Itzchok-Izik, Matei | Icek, Mircia, Mechel, Summer, Liby | Moses, Reisel |

| Engelstein | Kleinberg | Rinzler | Udelsmann |

| Jacob, Esther | Moses, Clara | Chaskel, Beila, Israel, Szymon, Gitel | Jacob, Malke-Rose |

| Falik | Kletter | Rinzler | Wachter |

| Abraham, Leah | Morris, Sarrah | Alter, Blimcia, Chaim | Devorah, Leib, Yosel |

| Faust | Kletter | Rosenberg | Wohl Family |

| Rubin, Anna | Samuel, Sara | Burach, Ruchel, Sally | |

| Feuer | Knisbacher | Rosenberg | Zimmerman |

| Meier, Pecie | Dov, Ciril | Solomon, Golda | Chaim, Ziena |

| Forsetzer | Knisbacher | Schleifer | Zweig |

| Leiser, Bincie | Meyer, Eidel | Leib, Sara-Gitel, Mendel | David, Eve |

| Zweig

Isaac, Elka |

|||

On October 2, 1983, the 41st Anniversary of the destruction of the holy community of Ottynia by the Nazis, the Ottynier Society in Israel erected a monument at Holon Cemetery dedicated to the memory of those who perished in the Holocaust.

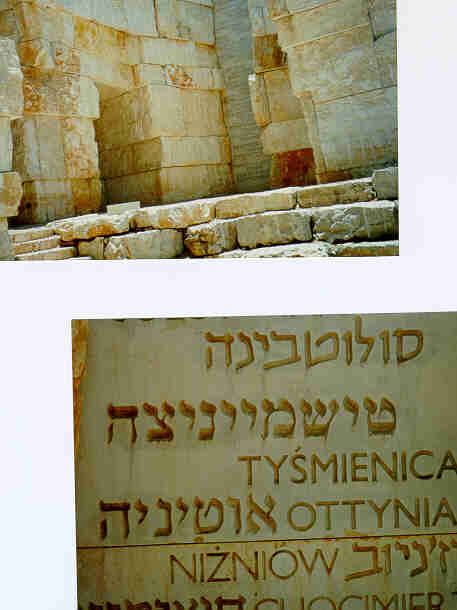

Valley of the Communities, Yad Vashem

The Valley of the Communities at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem has a section

devoted to the destroyed shtetlach of Galicia including Ottynia.

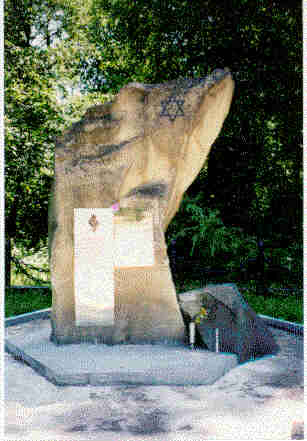

The Szeparowce (Sheparivtsi in Ukrainian) Forest is the site where thousands

of Jews from Kolomyja and surrounding towns including Otynya were murdered

by the Nazis. In 1993 a group of 28 survivors from Kolomyja, led

by David David of Milwaukee, Wisconsin returned to Ukraine to dedicate this monument at the

edge of the Szeparowce Forest on the side of the road between Otynya and

Kolomyja. The monument has plaques in Hebrew, Yiddish and Ukrainian

designed by the Organization of the Descendants of Kolomyja in Israel.

The Hebrew plaque may be translated as:

Milwaukee, Wisconsin returned to Ukraine to dedicate this monument at the

edge of the Szeparowce Forest on the side of the road between Otynya and

Kolomyja. The monument has plaques in Hebrew, Yiddish and Ukrainian

designed by the Organization of the Descendants of Kolomyja in Israel.

The Hebrew plaque may be translated as:

“In eternal memory of the Jews from Kolomyja and surroundings who were murdered here at the hands of the cruel Nazis and their helpers during the years 1941 – 1944.”

The Ukrainian portion of the monument was vandalized in June, 1994.

A protest was filed with the Ukrainian Ambassador to the United States

by David David. Several months later a new Ukrainian plaque was installed

and arrangements were made for ongoing maintenance.

In “Every Day Remembrance Day”, Simon Wiesenthal records July 7, 1941 as the day Ukrainians killed 1,200 Jews in a forest near Otynia. His entry for August 18, 1941 states: “The Ukrainian police take 2,000 Jews out of the ghetto of Kolomyja on the Prut River in the Ukraine, and, intending to shoot them, drive them to a forest nearby. But the Hungarian commander in chief prevents the execution.”

One of the witnesses at the trial of Adolf Eichmann was Shmuel Horowitz of Holon, Israel. Mr. Horowitz was a tailor ordered to work for the Gestapo in Kolomyja from 1941 until the end of 1943. He testified that soon after the German entered Kolomyja in 1941, the SS and Schutzpolizei came to Kolomyja and placed barrels of gasoline in the great synagogue and destroyed it. The next day they said there were communists hiding in the Jewish quarter so they carried out an enormous aktion and took away about 2,000 people. They were locked up and kept alive for a few days and then driven in closed trucks to the Szeparowce Forest where they were all shot dead.

Blanca Rosenberg, in her autobiograpical book, “To Tell at Last”, relates what a boy who survived the shootings reported to her:

The victims were forced to dig their graves by the light of lanterns the Ukrainian guards held over them. Then they were commanded to strip to the skin. One of the guards took out a harmonica and the victims were ordered to dance. When the Jews failed to obey, they were set upon with truncheons. Following the entertainment, they were sent through a close order drill by the German officers: attention, at ease, squat down, jump run… When the fun was over, the Jews were ordered to face the trench they had dug. The firing began.

Elie Wiesel’s friend and mentor, Moshe the Beadle, also experienced the horrors of an aktion in the Szeparowce Forest. Moshe was not a Hungarian so he was deported from Wiesel’s hometown of Sighet at the end of 1941. In “Night” Wiesel writes:

The train full of deportees had crossed the Hungarian frontier and on Polish territory had been taken in charge by the Gestapo. There it stopped. The Jews had to get out and climb on to lorries. The lorries drove toward a forest. The Jews were made to get out. They were made to dig huge graves. When they finished their work, the Gestapo began theirs. Without passion, without haste, they slaughtered their prisoners. Each one had to go up to the hole and present his neck. Babies were thrown into the air and the machine gunners used them as targets. This was in the forest of Galicia near Kolomyja. How had Moshe the Beadle survived? Miraculously. He was wounded in the leg and taken for dead.

At the end of January, 1942 the Jews of Kolomyja who had been deported from Germany to Poland in 1939 had to register at Gestapo Headquarters. They were then taken to Szeparowce Forest. According to Blanca Rosenberg 1,200 Jews with foreign passports were shot in that day’s aktion.

Through most of 1942 the Szeparowce Forest was silent. The Germans rounded

up Jews from the Kolomyja ghetto and transported them in cattle cars to

the concentration camp at Belzec. However in February, 1943 the Nazis

decided to make Kolomyja judenrein and again they chose to use the

Szeparowce Forest as their venue for murder. Wiesenthal states

that a total of 1,500 persons were shot there during this final aktion.

Horowitz testified that 6,000 people had been taken to the Criminal Police

for the last transport to the Szeparowce Forest and shot there.

References

Simon Wiesenthal, “Every Day Remembrance Day”, Henry Holt and Company, New York, 1987

The Trial of Adolf Eichmann, Session 30, Part 2 of 7, http://www.nizkor.org/hweb/people/e/eichmann-adolf/transcripts/Sessions/Session-030-02.html

Elie Wiesel, “Night”, Hill & Wang, New York, 1960

Blanca Rosenberg, “To Tell at Last”, University of Illinois Press, Urbana

and Chicago, 1993

Traveling to Otynya

by Phil Spiegel

Why did the Spiegels want to go there?

My father, Sol Spiegel, was born in Otynya in 1903. Helen Dulberg Spiegel, my mother, was born two years later in the village of Uhorniki (Hornig in Yiddish) which is about 2 miles from the center of Otynya. During World War I, when the Russians overran the area, the Spiegel and Dulberg families found refuge in a safer part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in what is now the Czech Republic. Sol and Helen became friends and were able to return to their homes in Poland when the war ended. The Spiegel family emigrated to America in 1920. My father worked as a seltzer salesman and studied English in Cleveland, Ohio. My mother went to high school in Stanislavov, Poland (now Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine). They exchanged letters and by 1928 Sol had enough money for a wedding and travel between Cleveland and Otynya – round trip for him and one-way for Helen.

My mother had two older sisters who had emigrated to New York with their husbands. Ephaim, a younger brother, emigrated to Argentina. But her youngest sister, Clara, and two younger brothers, Shmuel and David, were still living in Poland when World War II began. As a child during the war, I heard that terrible things were happening to Jews in Europe and I asked my mother about her siblings. She cried and told me that Shmuel and Clara were shot when the Nazis destroyed the Jewish community of Otynya and that David had joined the Russian armed forces but had not been heard from when the war ended.

Although he did not lose any close relatives in the Holocaust, my father held within his heart for many years a great sadness over the destruction of his shtetl. One day he told me that he always got a severe headache at the Kol Nidre service at the start of Yom Kippur. I asked why that was so since the fast was just beginning. He explained that it had nothing to do with fasting; it was the memory of Kol Nidre night in 1941 when the Nazis poured gasoline into a synagogue in Otynya that was filled with worshippers and set it ablaze.

When my wife, Carolyn, and I were in Israel in 1991 we visited the Yad Vashem archives. I was hoping to find information about Otynya but there was nothing in English. After we returned to California and attended a meeting of the San Francisco Bay Area Jewish Genealogical Society, I learned how I to do research about the community. I discovered that there was a history of the Jewish community of Otynya in the Pinkas HaKehilot, in Hebrew, published by Yad Vashem. With help from a Hebrew teacher I translated it into English. In July, 1998 the translation became the initial version of this ShtetLink.

My father was an active member and president of the First Ottynier Young Men’s Benevolent Association. Founded in 1900, it provided considerable support to new immigrants from Otynya to both America and Israel. In May, 2000 it will celebrate its 100th anniversary. My goal is to create a book in English about the Jewish community of Otynya for that event and help to preserve the memory of the Jewish community of Otynya for future generations. This ShtetLink will be the core of the book. As Carolyn and I planned to visit Otynya we had several objectives. Photographs and impressions of Otynya today would certainly enhance the web site. Perhaps I could learn more about what happened to my aunt and uncles by actually visiting the town. I wanted to see with my own eyes the place my parents came from.

What did the Spiegels find there?

During the summer of 1998 my son, Mike, and his girlfriend, Kristina Lamour, were working in London. They decided to tour Eastern Europe and include a visit to Otynya. At the 1998 Jewish Genealogy Society’s convention I heard excellent reports about a genealogical researcher, tour guide and interpreter who lives in Lviv, Ukraine named Alex Dunai. I also found an article in the Winter, 1997 issue of Avotanynu about a rabbi in Ivano-Frankivsk who has a treasure-trove of information on Galician Jewish history and genealogy. Its author, Susannah Juni, also spoke very highly of Alex Dunai. I sent all this information to Mike. He immediately contacted Dunai by e-mail and they made arrangements for a trip from Lviv to Otynya with side visits to Uhorniki and Tysmenica, my paternal grandmother’s hometown.

Mike and Kristina traveled to Lviv from Krakow, Poland by train. Alex Dunai met them in Lviv and drove them to Ivano-Frankisvsk while giving a brief lesson on Western Ukrainian history. They called on Rabbi Moshe-Leib Kolenik who was extremely gracious, charismatic and helpful. The rabbi took them through the former Jewish ghetto and to the Jewish cemetery. The next day Alex, Mike and Kristina went to a village called Uhorniki near Ivano-Frankivsk but no one there had ever heard of a family named Dulberg.

They then drove to Otynya. Alex talked several people in the street and learned that there was a local professor, named Mikhailo Havliuk, who was writing a history of Otynya. He has an office in the town administration building. A secretary there told the visitors that Havliuk was on vacation but she thought her neighbor might remember Mike’s grandparents. The secretary rode with Alex, Mike and Kristina to the home of Anna Slusarenko Nadvorniak who did indeed remember the Dulbergs. She also remembered that Feibisch Dulberg, my grandfather, owned a bakery next door to Anna’s father’s store. She pointed out that Uhorniki where the Dulbergs lived is only a mile from her house. This second and smaller Uhorniki was the next destination for Mike, Kristina and Alex. There they met an 83 year-old man named Petro Dubey who said he remembered the Dulbergs and even recalled the wedding of Helen Dulberg and Sol Spiegel. As a 12 year-old Petro saw Sol as a man from America who wore a suit and took photographs of the townspeople. “Somewhere in America there’s a picture of me,” he said.

Carolyn and I decided to travel to Otynya in June 1999 and follow up on Mike’s visits and meetings with Rabbi Kolesnik, Anna Nadvorniak and Petro Dubey. We also hoped to meet Mikhailo Havliuk. Alex Dunai met us at Lviv Airport upon our arrival from Warsaw. He drove us to Ivano-Frankivsk and we checked into the Hotel Roxolana, an oasis in a country where flush toilets are a luxury.

The next day we met Rabbi Kolesnik at the synagogue and learned about

the Jewish community of Ivano-Frankivsk – 150 people or 0.1 per cent of

the city’s population.  The

synagogue, sporadically supported by Chabad, has a dining room that serves

meals and has a minyan on Mondays, Thursdays and Saturdays.

The

synagogue, sporadically supported by Chabad, has a dining room that serves

meals and has a minyan on Mondays, Thursdays and Saturdays.

Rabbi Moshe-Leib Kolesnik is a native of Ivano-Frankivsk, only one of two rabbis in Ukraine who were not imported from America or Israel. Prior to becoming a rabbi he was teacher of Russian. As his father was a Communist party official, he was privileged to be sent to Moscow for further studies in Russian in 1984. There he met Rabbi Israel Kogan and for five years secretly added Judaic studies to his curriculum. After Ukraine became independent he returned to Ivano-Frankivsk to serve as rabbi for the city and about 25 surrounding communities.

We talked about Otynya and the destruction of its Jewish community during the Holocaust. He pointed out that before World War I the biggest synagogue in the region was in Otynya and that there were two Jewish newspapers published there. There were also four small synagogues in the town before World War II and one of them was burned down with people in it on a Jewish holiday. However, he said it is very hard to get documentation on events in Otynya because there was so much destruction there. The “front” came twice to Otynya and there were big battles each time. Actions against Jews started before the war with pogroms carried out by the local population. A Jewish woman reported that her parents and grandparents were killed and cut into pieces at their home. The first troops to occupy Otynya were the Hungarians in 1941. Some Jews from Otynya were brought to the ghetto in Stanislawow. Others were taken in trucks to the Szeparowce Forest and murdered.

The Jewish neighborhood in the center of Otynya no longer exists.

There are just remnants of the cemetery; no gravestones exist there.  A section of the Jewish cemetery in Ivano-Frankivsk is devoted to people

from Otynya including Rabbi Chaim Hager who

lived from 1864 to 1931. He was part of Wishnitzer dynasty of famous

rabbis. Rabbi Kolesnik gave me a picture of Rabbi Hager and showed

us his gravestone when we went to the cemetery. Over the past year

someone had built a protective cage around Rabbi Hager’s grave. The

inscription on the gravestone may be translated as: Here is buried

our teacher, the righteous Rabbi Chaim, may his memory be a blessing, from

Ottynia, author of books: "Comments of Chaim", "Dew of Chaim". Died on

Shabbat, the first day of Chanukah, 5692 (1931).

A section of the Jewish cemetery in Ivano-Frankivsk is devoted to people

from Otynya including Rabbi Chaim Hager who

lived from 1864 to 1931. He was part of Wishnitzer dynasty of famous

rabbis. Rabbi Kolesnik gave me a picture of Rabbi Hager and showed

us his gravestone when we went to the cemetery. Over the past year

someone had built a protective cage around Rabbi Hager’s grave. The

inscription on the gravestone may be translated as: Here is buried

our teacher, the righteous Rabbi Chaim, may his memory be a blessing, from

Ottynia, author of books: "Comments of Chaim", "Dew of Chaim". Died on

Shabbat, the first day of Chanukah, 5692 (1931).

Rabbi Kolesnik pulled out his file on Otynya for us. It had documents from 1925, in Polish, about Jewish community meetings. One of them had been rubber stamped with the name, Levi-Yitzhak Klüghaupt. He was the rabbi who officiated at my parents’ wedding.

I showed Rabbi Kolesnik a copy of my mother’s high school report card. He was able to direct us to the school building. However it is no longer Queen Vadiga (Polish) School; the Ukrainian sign on the front door calls it Elementary School # 7.

From the school in Ivano-Frankivsk we drove south toward Otynya. I thought we were in Kansas as the terrain is very flat. We shared the road with horse drawn carts and wagons as well as people walking their cows to and from pasture. More evidence that Ukraine isn’t participating in the global prosperity of 1999 came in the form of hundreds of partially built houses with no one working on finishing them. Alex explained that the economy just shriveled up in the past few years and finances are no longer available to finish construction.

Our first visit in Otynya was with Anna Nadvorniak who was born in 1923. She was delighted to meet us and served us homemade fruit compote as she reminisced about Jewish families who lived in Otynya before the war. She recalled the Baron, Dulberg, Forsetter, Hager, Kriegel, Rinzler, Rosenberg, Schreier, Spiegel, Steinhoren and Zimmerman families. She said that her father spoke perfect Yiddish and had many Jewish friends. When Otynya became part of the Soviet Union the family’s sausage business collapsed.

Her son and daughter-in-law live with her. They are doctors but they haven’t been paid for the last eight months. They survive by growing their own vegetables in their garden and by raising pigs and cattle. Anna’s pension is only 37 Hryvnia per month. This is about US$9 or what it cost to fill the gas tank of Alex’s Lada. Referring to the Russians as the “Muscovi”, Anna blames them for the economic problems. She said there are still many communists in the local government and in Kiev who don’t want to reform.

From Anna’s house we went to the center of town to find  Mikhailo

Havliuk, the history professor who was writing a book on Otynya.

He is currently the mayor of Otynya. It was Sunday and we found him at

the local sports club. He was delighted to meet some visitors from America

so he took us his office with us for a visit.

Mikhailo

Havliuk, the history professor who was writing a book on Otynya.

He is currently the mayor of Otynya. It was Sunday and we found him at

the local sports club. He was delighted to meet some visitors from America

so he took us his office with us for a visit.

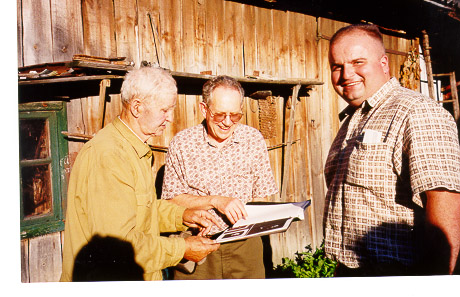

To our great surprise Mikhailo immediately gave Alex and me copies of his book on Otynya. They had been printed just two weeks prior to our visit. The book is in Ukrainian and consists of 148 pages with about 100 illustrations. He went through the book, pointing out items we would find interesting.

Mikhailo Havliuk (L) with Phil Spiegel

Documentation on Otynya dates back to 1144. It became a town in 1606.

The population of Otynya grew from 1100 in 1784 to 5000 in 1914. About 40% of the population in the 1900’s was Jewish.

The Baron Hirsch School was built in 1914. It was a large two-story school for Jewish boys and girls at first. Some time later the Hager School for Girls was established and the Baron Hirsch School was restricted to boys. It was destroyed during the war and a hospital stands on the site.

In the 1930s there were three synagogues in Otynya. Two old wooden ones were burned during the war. The third synagogue, built of bricks with two floors, was used for storing machines during the war and destroyed in 1952.

During the war 1,730 Jews were murdered in Otynya, starting during the summer of 1941 in the short-lived ghetto where now there is a supermarket. Some were shot in the Szeparowce Forest and others were taken to concentration camps. About 15 years ago a local worker told Havliuk that he was a witness to the one of the actions in the Szeparowce Forest. He related how an SS man went to a Jewish woman, seized her child by the feet and broke the child’s head.

On the road between Otynya and Kolomya there is a memorial honoring the Jews who were murdered in the Szeparowce Forest.

At Yad Vashem there is a tree in the Valley of the Righteous Gentiles named for the Lutsenko family. One Jew saved by them now lives in Australia.

Mikhailo Havliuk spoke about another project of his. He is also a musician and is gathering local songs. He finds many of them have Jewish origins. For example, “Hava Nagila” and “Zibin Fiertzig” are played at every Ukrainian wedding.

From the Otynya Administration Building we drove to the village of Uhorniki

to find 84 year old Petro Dubey. He was at home with his daughters

and grandchildren. I gave him photos taken by Michael last year and

showed him my parents’ wedding pictures.

.

L. to R: Petro Dubey, Phil Spiegel, Alex Dunai

He said he remembered the Dulberg family very well and could take us

to the place where they had lived.  The

Dulberg family home was destroyed during the war and a new house was built

on the site a few years ago.

The

Dulberg family home was destroyed during the war and a new house was built

on the site a few years ago.

While we were there he told us that he had been a slave laborer in Germany during the war. When he returned to Uhorniki he learned from others what had happened to one of my mother’s brothers. Shmuel, who had managed family’s grocery store was hidden with his friend Schmerler for a while but someone informed the Nazis about them. The Nazis seized them and forced them to dig their own graves and then shot them. The observer told Petro that the earth was still shaking after the earth was shoveled over them! Shmuel’s wife and daughter were shot in the Szeparowce Forest. My mother’s younger brother, David, had worked in the grocery delivering food to resorts in the Carpathian Mountains and in 1941 joined the Soviet Army. Petro did not know what had happened to David or to my mother’s youngest sister, Clara. He asked if another brother, Ephraim, was in Israel and I told him that he had emigrated to Argentina in the 1930’s and died there about 35 years ago.

The next day we visited Tysmenica where my great-grandfather, Berel

Spiegel, and my grandmother were born. We then drove to Kolomya and

saw the memorial at the Szeparowce Forest. From there we drove to

Pechenezhen, the birthplace of my grandfather, Chaim-Sholem Ratzer.

Alex thought that we might be able to find someone who remembered the Ratzer

family so he asked people on the street, “Who is the oldest person in this

town?” He was referred to a 101-year-old man named Mr. Kolyik who

lived in the hills overlooking the town. We found him and his daughter

but he didn’t remember anything. His daughter claimed that he had

hid den a Jew named Ancelowicz in his farmhouse during the war. We

also found the Jewish cemetery of Pechenzhen. It is in relatively good

shape and the people who live adjacent to it were helpful in allowing us

to go through their garden to enter it and in helping to keep some of the

gravestones intact. Our final visit of the day was to the picturesque resort

town of Jariemcza in the Carpathian Mountains.

The Return of Israel Rosenberg

Israel Rosenberg was born in Otynya in 1920 and joined the Soviet Army

in 1941. When the war ended he managed to get out of Siberia and

immigrated to the United States. He is an Ex-President of the First

Ottynier Young Men’s Benevolent Association. In 1996 he traveled

to Otynya with his wife and daughter. To his great surprise he found

his house still standing. It had settled deeper into the ground than

it was back in 1935 when it was built. Three families live there

now.

Israel Rosenberg is still fluent in Ukrainian. He met a 91-year-old woman who confessed to him, “My husband was a drunkard; he robbed and killed Jews!” The Rosenbergs also drove to the memorial at the Szeparowce Forest and took a photograph of it.

If you are not fluent in Ukrainian and you are planning to do more than casual sightseeing, by all means get an interpreter. I highly recommend Alex Dunai. His English is excellent and he has a superb ability to find people who can help in genealogical research. He can be reached via email at dunai@iname.com or by telephone: 38-0322-337-769. His address is Oleny Stepanivny Street 17/2, Lviv, Ukraine 290016. He can also make hotel reservations for you. We were very pleased with the Roxolana Hotel in Ivano-Frankivsk.

Carolyn and I flew non-stop (70 minutes) on LOT Polish Airlines between Warsaw and Lviv. Mike and Kristina rode to Lviv by train from Krakow. It takes about nine hours because the train stops for 2 to 3 hours at the Polish-Ukrainian border near Przemysl to have its wheels changed.

Once you have received your itinerary, hotel reservations and train

or plane tickets you can apply for a visa to enter Ukraine. This

can be done by mail to the Ukrainian Consulate in New York. It’s

best to call them at 212-371-5690 at least three weeks before your arrival

in Ukraine and ask for an application and the latest requirements or download

them from http://www.brama.com/ua-consulate/visa.html.

Page created by Phil Spiegel.

Latest Revision: 2/29/2016 PS

Copyright © 1998-2016 Phil Spiegel

ShtetLinks

Directory | JewishGen Home page

Link to

Gesher Galicia

Return to top of this page