Our Shtetl: Nagymegyer, Hungary, now Veľký Meder, Slovakia by Yehoshua Weiss |

|||||||

In the early 1940s, Nagymegyer was a small town, or a big village, of about 5,000 inhabitants, including a Jewish community of between 95 and 100 families (520 to 540 souls). It is situated between Bratislava and Komarno (Komárom). This region is an island, embraced by the Danube, from the South and its branch, the Small Danube, from the North. It is called Csallóköz (Žitný Ostrov in Slovakian), meaning Wheat Island, because of its fertile land that yields rich grain crops. The region changed political régimes during the first half of the twentieth century. Until the end of WWI it belonged to the Autro-Hungarian Monarchy; between 1918 and 1938 it was part of the Czechoslovak Republik; at the end of 1938 it was reattached to Hungary; and since the end of WWII, it has belonged to Slovakia.

The Jewish community was Orthodox and conducted an organized community life. It had a Rabbi, a cantor, a slaughterer, two teachers, two Melamdim (Torah teachers of children) and a synagogue attendant. It owned a spacious synagogue, a Beit Midrash (a special facility for adults studying Torah), a Talmud Torah (a school of religious Torah studies) of two classrooms, a basic school of two classrooms, a slaughterhouse and a Mikve (a ritual bath). Some voluntary associations acted in the community: The Charity Association, that aided the poor; The Talmud Torah A., that supported the religious education of the children; The Chevra Kaddisha (the "holy society"), that cared for the arrangements concerning the dead, organizing the funerals and maintaining the cemetery; Chevrat Nashim (The Women’s Association), dealing with charity and supporting, aiding needy women; and, maybe, some others. Their budgets came from donations of people called to the Torah on Saturdays and Holidays. Some generous community members made anonymous donations before the High Holidays.

The chairman of the community, the Rosh Hakahal, and the leading committee were elected once a year in the Beit Hamidrash by the general assembly of the community members who had paid their taxes. This assembly had to approve of the budget for the coming year. These occasions were always rather stormy, because the budget forecast was always deficient and the assembly had to decide what expenses should be reduced. There always was a group that wanted to “crop” the salaries of the community employees, mainly that of the Rabbi. Others fought vehemently to spare the Rabbi the abashment, the humiliation of decreasing his family’s standard of living. This battle repeated itself every time, before the general assembly and the election. A severe rift developed in the community around this issue. A certain part of the members, practically, separated themselves from the services in the synogogue and kept them in the classrooms of the Talmud Torah. They no longer recognized the Rabbinic authority. This happened due to the influence of a couple of young Chareidim, religious fanatics who had married local Jewish girls and managed to spread their ideas and “ideology” among those people who, gradually, became their “fans”. This process started some time about the mid 1930s, but it was not always so. Since its founding at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the community was strictly observant, but moderate. It led a peaceful life and everybody minded his own business. The first Rabbi of the community, Yoseph Dov Lock, (my Great Grandfather) a most cherished and praised pupil of the famous Orthodox rabbi and teacher Rabbi Moshe Schreiber (Rav Moshe Sofer in Hebrew), who is known for his main work Chatam Sofer, translated as Seal of the Scribe. Lock, who was in office from 1860-1880, was a man who always sought peace and even on his tombstone it was engraved that he was a man of mediation. During these years, the community developed peacefully and there is no record was found about controversy within the community.

During the forty years of his successor, his son-in-law Rabbi Yehoshua-Heshl Weiss (my Grandfather), this situation did not change. All the community members honored their spiritual leader, whose fame reached even the remote communities of the Monarchy and were loyal to him during the long years of his service (1880–1920). Like his father in law, he bequeathed his rabbinical position to his scholarly son-in-law, Rabbi Shimon Shatin (1920–1938), who had married his daughter, Beile Haye. As previously discussed, he conducted his service peacefully, until the new ideas began to undermine his authority and embitter his and his family’s lives. He also wanted to leave the high office to his son-in-law, Rabbi Pinkhas Asher Goldberger, but due to the controversy and the opposition of the Chareidim, only the “loyal” part of the community accepted him as Rabbi. In 1944, the whole community was deported to Auschwitz along with Rabbi Goldberger with his wife and three children, his brother in law and three sisters-in-law. Only Rabbi Goldberger and his youngest sister-in-law, Adele, returned from the infernal “journey”. They married and, shortly afterward, immigrated to the United States. Rabbi Pinkhas established a new community and a Shul (a small synagogue) in Forest Hills, New York. He was well known in the Orthodox circles of New York. He passed away some years ago and was put to his eternal rest in the Har Hamenuhot cemetery in Jerusalem, where he and his wife had brought her both parents’ and the remains of our Grandfather Rabbi Yehoshua Heshl Weiss, from the Nagymegyeri cemetery, years earlier. This was the end of our Rabbinical “dynasty”. Apart of the succession of Rabbis, the community conducted its normal life. The Jewish families occupied the Main Square and the commercial life of the town was concentrated there. The Catholic population, with their church and graveyard, lived at one end of the town, the Evangelic occupied the other end, whereas the Jews, with their shops, kept to the center of the town. Very few of them lived on the outskirts, among the Gentiles. There were no officials among them. Neither the Monarchy, nor even the Czechoslovak Republic liked Jews in official positions, not to speak about the Hungarian Horthy régime. Most families were low middle class but there were a few well-to-do, or even rich ones. Apart of shopkeepers and merchants of all kinds, there were quite a few craftsmen, tinkers, carpenters, watchmakers, jewelers and tailors.

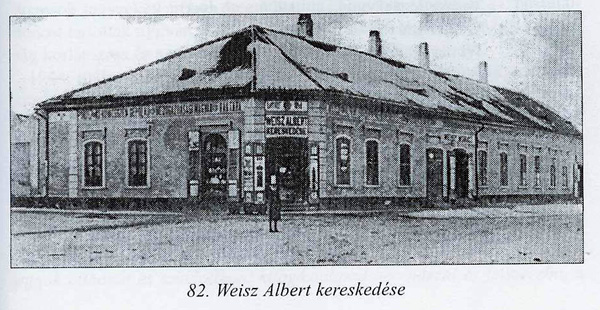

The local historian, Mr. Varga, has, recently, “unearthed” from the municipal archives, an old picture of a warehouse, situated in the very center of the town, that belonged to Mr. Albert Weisz in the middle of the nineteenth century. The house still exists, although after some alterations. Our basic school of 8 grades had two classrooms, where two teachers taught about 100 pupils. The Small School contained grades 1 through 3 and the Big School the remaining 5. The Small School teacher divided his time between the first grade and the second and third grades. While he was busy with one group, the other one had to do a writing job. The groups learned with the teacher for half an hour and made written lessons during the other half. The pupils of the Big School learned in the same way. The grades 4 and 5 were in one group and the grades 6 through 8 were in the other one. It seems, even to me, now, rather absurd, but it worked. Our school always was the best one among the three local ones. The district inspector of the ministry of education visited all the schools before the end of every quarter. After every visit, he had to admit, to the community board of education, that our Jewish school was the most advanced and had the highest qualification, not only among the three local schools, but it was the leading one in the whole county. These officials never liked to praise anything Jewish, but, in this case, he had no choice. I lovingly remember that school, where the old headmaster taught us, not only grammar and math, but also good manners and proper behavior, for lifelong use. The valuable knowledge we acquired in that strange school, has remained with us until old age. On Fridays, the last lesson was borrowing books from the library of the school. There were all kinds of books in that library, for all levels and ages. This happened under the supervision of the teachers, who cared that all the pupils get the suitable books. I acquired my reading habits, my attraction to books, owing to that precious library of my early childhood. |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||