Our 1974 European Tour

by Lili Susser

|

Lili Susser (Cukier), survivor of the Lodz ghetto and Auschwitz,

is the author of a self published book about

her experiences during the Holocaust. Click the images for a larger view.

|

|

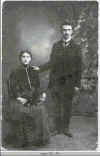

Lili's mother, Chaja Malka Rubinsztajn, circa 1910-1912, with Chaja's

brother, Theodor (Tevie) Rubinsztajn. Lili's mother was born in 1891 in

Plock, a town north of Lodz. This is the only photo Lili has of her family. |

NOTE: The following is Chapter I of "Our 1974 European Tour," a short story

by Lili Susser. Chapters II, III and IV deal with Krakow, Venice and Paris.

Ever

since being forced from my home by the Germans during the war in 1940,

my desire was to go back some day. I don’t know why, but I had this need

to see the place that was my home once again, perhaps to relive the past,

the “good and carefree” years when my family was still intact. I fantasized

for years about going there, knocking on the door to our apartment, and

asking the present tenant to please let me in for just a look to recover

some of those memories.

Travel to Poland before

1974 was next to impossible because of the cold war, and Poland was an

“Iron Curtain” country. Later when travel restriction eased, it was on

a small scale, on a guided tour only and to a select few cities, namely

those with tourist attractions. This did not interest me since Lodz, my

home, was not on their itinerary.

In 1974 restrictions

eased again and this time individual traveling was permitted to former

citizens of Poland. We applied and were granted entry visas. It was going

to be our first trip to Europe since our arrival in the USA in 1949. After

all these years of dreaming about returning to Poland, I never believed

it would come true and now the time was upon us.

Our main destination

was Germany, particularly Georgensgmund, where we had lived after having

been liberated from the concentration camps and where our son Herman was

born. We had friends there with whom we had stayed in touch all this time

and we decided to take them up on their frequent invitations to come for

a visit. It had been nearly 25 years since we had left there and I was

curious to see the place and the many friends. Mary was graduating college

and decided to get a bank loan so she could accompany us on the trip before

she started work. Once she got a job she may not have been able to get

time off. I longed to go to Poland just to see what it was like. I missed

my home and my friends. Although I knew they were all gone, something within

me would not let me come to terms with it. For years I had thought up ways

of approaching the people who must live in our apartment now, to ask them

to let me in for a look. That’s all I wanted, just a look. I don’t know

why the longing was so intense, and I certainly got enough flack from people

I dared mention it to. “Why do you want to go back there, didn’t you get

enough of it?” But, what I was looking for was what I had before the war.

There was a time, after all, when I had a happy home, a childhood. Perhaps

I was looking to find myself, my youth. Secretly I hoped everything to

be the way it was when I left; that what I experienced was just a bad nightmare

from which I would wake up once there. Maybe this is what I needed to face.

Could I possibly find any of my non-Jewish friends? Perhaps I wanted to

confront the ghosts that were haunting me every night since liberation.

I didn’t have answers to any of the questions. I just had this nagging

need to go back and I didn’t know why. It had been 34 years since I last

saw my home and now that we were going to Germany, it would be a good opportunity

to make a side trip there. Julius was very much against going to Poland!

He was apprehensive, and with good reasons: the television was portraying

the Iron Curtain countries as treacherous villains. The movies and news

articles were emphasizing the dangers one faced traveling in those countries.

For instance, hotel rooms being “bugged,” the KGB were following and spying

on tourists, people were being arrested and imprisoned for no reason, authorities

were manufacturing evidence and having false charges brought against you,

and generally, visitors were being mistreated and perhaps even being detained.

Eventually, I was able to convince Julius that we could get a visa for

10 days, and if we felt uncomfortable or threatened in any way we could

head back to Germany. We told our kids that if they didn’t hear from us

in a couple of weeks, “call a senator, congressman, the President, whoever

it takes, to let them know we were being held “against our will”. In order

to get our visas, we were to send $17.00 per person, in American money,

for each day of stay requested, to the Polish consulate in exchange for

vouchers redeemable for Polish zlotys upon arrival in Poland. The money

was not otherwise refundable. The kids came to see us off at the Denver

airport and we were on our way.

We arrived in

Georgensgmund the following day and were guests of our old friends and

former landlords, the Riegelbauers. We were treated royally, but in all

this excitement I developed a terrific headache and had to go to bed to

cure it. After a short nap, I felt somewhat better. Friends started coming

by to see us. We had a lot to catch up on. Then, we went for a walk to

see the town. The changes were enormous. Like in the United States, new

buildings had sprung up, making some of the old places unrecognizable to

me. The people, however, recognized us and called to us from windows. Some

invited us for refreshments and would not let us leave until we had some.

As we walked in our old neighborhood, I looked in store windows. The neighborhood

had changed. There was now a new shoe store where before there were only

houses. As I checked out the goods in the window, I heard someone holler

from across the street, “Almighty God this can’t be anyone else but

the Sussers!” I turned to see a young woman in the front of the house.

At first I did not recognize her, but I recognized the house she was in

front of as the Schilling house. “You must be Gretel?” I asked. She was

just a child when we left and now she was a young married woman with children.

After a couple

days of rest, we went to Poland on the Polish airline, LOT. It was a short,

pleasant flight to Warsaw, the Capitol. We got off the plane with mixed

emotions—some excitement and some apprehension. For one thing, this used

to be my home and I missed certain aspects of it. This is where I grew

up, went to school, made friends. It was a carefree time. Then the storm

of war came and turned everything upside down. Here is where I learned

what starvation, cold, hunger, death, fear and extreme brutality were.

Apprehension of the unknown dimmed, at times, the excitement of having

arrived at the place I so often visited in my dreams. Julius headed for

the money exchange and Mary and I waited with the luggage. We had only

two suitcases and little cash or traveler’s checks, having left most of

it in Germany, just to be on the safe side. While Julius was gone, a man

approached, offering us a private cab fare to our destination. I told him

I was not sure what this might be, as we had not discussed it before hand.

We intended to go to Lodz, my hometown, and Krakow, Julius’ home, but had

not set priorities. We just expected to take a train to whichever came

first. "Well!" he said, "I’ll take you wherever you decide." When

Julius returned, we decided. Since Lodz was closer, we would go there first.

I asked the stranger what he would charge to take us there. His fee was

$100.00 in American money. While I had no sense of monetary value in Poland,

I knew that I was not going to pay $100.00 for approximately 120 kilometers.

I decided to make some inquiries. I walked up to a couple of men who had

come on the same plane from Frankfurt. They were Polish, but lived in Florida,

and visited their mother in Poland every year. I asked them what would

be a reasonable offer. They thought $20.00 should be sufficient and I took

the offer to the stranger. No, he could not accept it because it was a

long drive and he would have to come back "empty." We decided we did not

mind public transportation and were just about to board the airport shuttle

when the stranger walked up to us and whispered, "OK, I’ll take the $20.00."

"Well," I said, "you are a little late because our luggage is in the bus

already." "I know," he said, "I already spoke to the driver and he knows

I’m going to follow him into the blocks (the residential area). He’s to

drop you off there and I’ll pick you up." Since Polish is my native language,

I had no problem with the conversation, but rules of the country and motives

of its citizens were rather hard to understand. Many things came to mind,

but at a slow pace and not until a new situation presented itself. At the

time, we had no idea what the "blocks" were. How did the stranger know

we were Americans? (We found out later by the shoes and luggage.)

Who was he and what were his motives? Was he a member of the KGB baiting

us to do something illegal? There was no time for questions, only a "yes"

or "no" and I said yes, not knowing what I said yes to.

A few streets

into a residential area, the bus stopped and the driver announced, "This

is where you get off." My heart sank! What are they planning on doing to

us? I thought. But, by the time we were climbing from the bus, the

driver was moving our luggage into the stranger’s car. He had obviously

followed us as he said he would. We got in the cab, which did not have

a taxi sign, and placed ourselves at the mercy of the driver. The first

words the driver uttered to us were, "Do you have any dollars to exchange?"

Again a fearful moment. Was he trying to catch us at committing something

unlawful? The literature from the consulate warned us against deals

of this sort as illegal and severely punishable. "No," we said, "we already

made the exchange at the airport just as required by law." "Well," said

the stranger, "I could offer you three times the legal exchange. For instance,

you probably got 33.00 zloty per dollar and I’ll offer you a hundred."

Our fear increased. We stood our ground—we did not intend to do anything

illegal. Now, we found ourselves going through a forested area. It was

raining and there was hardly any traffic. The stranger put a folded newspaper

between the seats in the front and announced, "Now I get paid. Just put

the money in the paper." I can not describe the fear I felt at that moment.

What would stop him from taking our money forcibly and driving off, leaving

us stranded in the forest? What if he wanted the money bad enough? What

would keep him from harming us, taking what he wanted and leaving us to

be found dead? My brave husband said, "No, you’ll get it when we arrive

at the hotel." "What hotel are you going to?" The driver asked. "We don’t

know any hotels in Lodz. Can’t you recommend something?" "No," he

answered, "I have only been there once." "What do you mean you have been

there only once? Don’t you drive there regularly?" I inquired. "No, I am

not allowed to leave Warsaw. This is why I don’t have my sign up. My license

permits me to drive in Warsaw only," he replied. The only Hotel in Lodz

I knew was the Grand Hotel, which was really as grand as I remembered it,

but that was ages ago and it was old already then. Would it have withstood

the war—the Soviet occupation? "Yes, the Grand is still there," he said.

"Let’s go there then."

As we were leaving

Warsaw, I remembered a message my family had received from the Red Cross

in 1939, just before we were sent to the ghetto. The words are still engraved

in my memory. They told us that my brother, Herman, had been killed in

a battle in the defense of the capitol and was buried in a mass grave on

the estate, Czerwonka, "under" Warsaw. I had always wanted to find

this estate and wondered, if this may not be the opportunity I had been

waiting for—if perhaps this might be near by. I asked the driver, "Are

you a Warsaw native?" "What do you mean by native?" "Have you lived here

all your life?" "No." "Are you familiar with the area?" "What area?" "The

area around Warsaw. There was supposed to have been a heavy battle during

the war in defense of Warsaw, in which my brother was killed. Do you know

where this took place?" "No, I am from the east and have lived here only

a short time. Here is a map. See if you find something familiar." He handed

me a map of the Warsaw region. There in the center, in big letters, the

word Warszawa and nothing else close by. Further down, I noticed the lone

name of a city, "Sochaczew." I didn’t understand why this should make an

impression on me since it was not the name of a town I recalled, but my

heart was racing. There was something familiar about it, I didn’t know

what. No other city on the map had this effect on me. I returned the map

and mumbled, "The name Sochaczew strikes a note, but I don’t know why."

"Well, we are in Sochaczew now. I’ll ask around," announced the driver.

"Just ask for the Estate Czerwonka, there is supposed to be a mass grave,"

I responded. At the market square, the driver parked the cab and went up

to another cab driver for information. "Yes," he said, "There is this estate

about a block from here." We drove to the estate and found it overgrown

with weeds the height of a human being. It was about 6:00 p.m., raining,

and a long way from Lodz, but the driver pressed on. He was not giving

up on the mission of finding the graves. He located the caretaker, who

informed us that, indeed, there had been mass graves here holding the remains

of soldiers, but they were exhumed a couple of years earlier by the communist

regime and transferred to the local cemetery. In spite of Julius’ objections,

we went to the cemetery, a short distance away, and found a large number

of military graves. They were marked by the usual stone cross with a little

plaque identifying the dead soldier when the name was available. Otherwise,

they were marked "His Holy Memory [Soldier’s Name]", or, "His Holy Memory,

Unknown Soldier", or simply "Soldiers," if they held several bodies. Part

of my mission was now completed. I was happy I finally found my brothers

burial site, although not his grave. Now, too, we were relieved to know

that the cab driver was decent. He was also extremely helpful—far beyond

the call of duty. How many cab drivers would have gone to this much trouble

to help some Americans look for a grave? We decided to comply with his

wishes and pay for his fare in advance and exchange a larger amount of

money with him. It benefited both of us. The rest of the drive was uneventful.

Soon, we arrived

at the Grand Hotel. It did not even closely resemble the splendor I remembered.

Before I had time to slide out of the cab our suitcases were on the sidewalk

and the cab was gone. None of us knew what happened or why. We were suddenly

on the sidewalk like dropped from the sky. It was still raining and the

bellhop, in uniform and white gloves, came to get our luggage. We followed

him inside and I recognized, immediately, the old Otis elevator across

the entrance. Obviously, it had never been replaced from the time the hotel

was built. This was like a freight elevator you would see in a warehouse,

with the iron grating that clanked and squealed when in motion. We walked

up to the desk to ask for a room. The clerk asked, "Do you want a room

or a suite?" (Apparently Americans were able to afford the best.) When

she said "suite," I visualized one of those you see on TV with all the

comforts. "That’ll be fine, we’ll take the suite," I responded. "May I

have your passports?" We handed the clerk our passports. "You’ll get them

back tomorrow," she said, blandly. "Tomorrow!" I retorted, a little shocked.

"And what do we do for today if we want to go outside?" "What do you need

the passports for? You just go where you want." What if we are stopped?

We have no other identification." "Who do you expect to stop you?" "Well…

the police." "Just show them the hotel registration and you’ll be fine."

Reluctantly, we left the desk and went to our "suite." We had to take the

creaky elevator—which gave me the creeps—to the second floor. The suite

had two sets of heavy doors, like double windows, one in front of the other.

There was a key lock on each door and a chain for safety. A warning was

posted on the inside of the door to keep it locked at all times. We had

two large-sized rooms looking out the front. One room had two comfortable

beds, the other a couch and a table and chairs in the center. The bathroom

must never have had a coat of paint since it was built and the stool’s

plumbing was old and rusty. The water tank, with the old-fashioned pull

chain, hung from the wall near the ceiling. The first time we used the

stool, it plugged up and it took a whole day to have it cleared. The toilet

paper resembled crepe paper, only it was a dirty gray and much coarser—more

like sandpaper. But we were fortunate: the natives had to share a communal

bathroom down the hall.

I was anxious

to go outside and see what was left of my memories. First, we stopped at

the hotel’s restaurant for a bite to eat. Like the old times, the piano

player played an old romantic song from long, long ago, bringing back a

flood of memories and giving me goose bumps. At least here, at the hotel,

nothing seemed to have changed except for being badly run down. We went

outside and walked the street. This was the street where I had lived before

the war—we were just a few blocks from my home. This is where I walked

in my dreams all those years. It held a lot of memories. To my surprise,

the street and the houses had not changed at all, and even some of the

businesses looked the same. Here was the shoe store, "Renoma." I remember

this was where my mother tried to talk me out of buying a pair of shoes

that were too small for me. I insisted they fit because the clerk pointed

out to my mother it was salamander leather. That is what sold them to me.

Never mind I could not wear them, after all. Buildings in this part of

the world housed apartments, businesses, and factories alike. Here was

the house where I used to come to check out books from a private library.

Here was another that housed a blanket factory where my brother held his

first job. Here, time stood still. It was very emotional for me. It was

getting dark so we returned to the hotel. Now, Julius brought up a thought.

What if the money we exchanged with the cab driver was counterfeit?

What if we were to be asked how come we have more than we exchanged at

the Airport? What if? What if? Julius decided he would take a few bank

notes and try to exchange them with the desk clerk so we could compare

them with the other bills. The excuse he used was that they gave him too

many small bills at the airport and they did not fit in his wallet. When

he returned we compared the bills and they looked genuine.

Next morning we

set out to see the house on Piotrkowska St. 116 where I lived before being

deported to the Ghetto. The stores in the front of the building looked

the same as the day I left 35 years earlier with few exceptions. The lingerie

store was still there in the same place. Inside the courtyard, I was shocked

to find the air raid shelter just the way I left it, the rocks piled in

front of the entrance never touched by time. It gave me an eerie feeling.

The whole house was in great neglect. Over the years that I was gone, the

house had not shown any improvements or even basic upkeep. The only difference

was that the whole rear section of the house where I used to live, and

where a neighbor had his stocking factory, was torn down—gone! At the time,

I didn’t think of knocking on a neighbor’s apartment for a look inside.

The apartment would have been much the same as ours. I was too nervous

and tense. The house next door, which formed a complex with ours, also

looked the same as I remembered it. All the trade shops looked just like

I had left them, up to the smallest detail, including the school of higher

learning, which I used to be able to see from our apartment windows. Next,

we went to the house I lived in before I entered school. It also has not

changed; the little grocery store in front looked just the way it did when

I lived there, as if I never left. In spite of dreaming and preparing,

all those years, for the eventuality of seeing my house again—how I’d knock

on the door of the apartment and ask to be permitted in for a glance—when

I was in front of the house, my courage abandoned me. The park across the

street looked, to me, exactly the way I remembered it, including the "Buckeye

alley" where I used to play so often. Only the fence that used to surround

it was no longer there. The communists believed fences should not keep

people out of places that were "theirs"—the peoples. Even the market square

across the street was as before, except no stalls, no sellers or buyers—empty.

This was in contrast to the market I remembered, which was teeming with

people and goods, from fresh produce and flowers to live fowl. A square

without a market. As a matter of fact there was nothing to buy in the stores

now. If anything became available one could tell by the long lines. The

houses were badly in need of repair and the sidewalks were full of chuckholes,

making walking difficult. I stopped at a store to buy a couple of infants’

shirts to bring back just for fun. The style dated back to pre war times.

No one in the US would want to use one of these on their baby. We spent

the whole day walking, comparing sites to what I remembered. It was very

confusing as names of some streets had changed and some houses had been

torn down, turning what were once courtyards into streets or a little neighborhood

parks.

The next day I

wanted to see the Ghetto area. Mary was not feeling well and chose to stay

in bed. We decided to get a cab. This was not as easy as imagined. We had

to go to a taxi stop and wait in line. There were a few people ahead of

us. As we waited, a couple of men spotted our movie camera and struck up

a conversation. My husband made the fatal mistake of wearing the camera

around his neck—something I warned him against. I wished to keep it in

a bag, concealed, so we could avoid publicizing we were foreigners, especially

in a country where even bare necessities are unavailable. As I expected,

the camera did arouse a lot of curiosity. "What kind of camera is it? Where

are you from?" they asked. We spoke good Polish, but were not dressed as

Poles. "How long were you gone from Poland? 35 years?" One man took my

hand and kissed it as a sign of courtesy. To have been gone so long and

speak the language so well was amazing to him and deserving of respect.

The other man was so drunk he could barely stand on his feet. Several cabs

pulled up to pick up the waiting fares. The sober stranger offered us his

cab. We declined. The other man was not as easy to shake. He was determined

to show us Lodz. No matter what, we could not get rid of him or his overbearing

courtesy. Just when we thought we had convinced him to leave us alone,

he opened the cab door for us and as I was about to sit down he pushed

his way in before we could drive off telling the driver where to go. We

were flabbergasted, but afraid to "rock the boat." First, he took us to

the newly built theater, which was very impressive. He ushered us in and

convinced the guard to let us look inside the theater where a meeting of

communist party members was taking place. I was uncomfortable, but there

was no way out. I did not want to tell him I was anxious to see the Ghetto

area and I doubt he would have listened. He was our guide and was obligated

to show us places of interest to him and therefore to us. Next, he drove

us to Radogoszcz, a suburb of Lodz, to show us the remnants of a factory

where the Germans had gathered about 1000 Poles, sprayed the building with

gasoline, and set it afire, killing all but a few. A survivor, who had

a badly scarred face, told us he had survived by hiding in a water tank.

He also led us to a monument for 10,000 children on the site of a former

children’s camp. The monument was of a big heart with a hole through it,

symbolizing a mother’s heart. Now our host insisted we go to his house

where his wife would fix us a dinner of traditional pierogis, and bigos,

and he would treat us to vodka and other nonsense, too ridiculous to mention.

The situation was getting scarier by the minute. I was trying to convince

him that our daughter was sick and we needed to look in on her. He wanted

to go with us to the hotel, call an ambulance, and have her treated properly

in a hospital. "It is socialized medicine, you know, free to everybody,"

he told us. I was out of breath and excuses, so I whispered to Julius to

take him to the bar in the hotel and buy him enough drinks to knock him

out while I went upstairs to the room with some hot tea for Mary. It finally

worked and a short while later Julius came to the room alone.

We took a cab,

alone this time, to the Ghetto area, but there I found nothing familiar.

A lot of houses, including the one I had lived in, were torn down. Sometimes

the apartments on one whole side of the street were torn down, as were

those behind them, thus making one wide street out of two narrow ones.

Here, I saw a lot of new housing, too. The decrepit little houses of the

ghetto were being replaced by apartment buildings, several stories high.

The waiting time for an apartment was 10 years! This is why newlyweds

lived with their parents for years. We drove around a little longer, then

headed for the hotel. My mission was accomplished. Having seen Lodz, we

were now going to Julius’ hometown of Krakow.

Lili Susser (Cukier)

Pueblo, Colorado

E-mail: susserl@mindspring.com

|