Recollections of Julius Bier. A transcript of a taped interview.

Submitted by Mary Bier Wilson.

Julius Bier

Born: September 9, 1870

Died: December 27, 1963

INTERVIEWER: Gerald Frolow-subjectís grandson

TRANSCRIBER: Mary Bier Wilson-subjectís granddaughter

Transcriberís note: Some of the verbatim text has been edited for clarity.

[...]-transcriberís comment

Gerald Frolow-his questions and comments in italics

Julius Bier-his commentary in bold

Whatís your name?

Julius Bier.

Whatís your name in Hebraic?

Ellah Bier (Elihuie)

Elihuie Ben what?

Ben Itzak

Elihuie Ben Itzak.

Thatís right. My name is Julius Bier. My Jewish name is Elihuie Ben Itzak.

Fine. What we are going to do today is that I want to get the whole story of what youíve been telling me all along. The story about when you first came here and what happened when you got here.

Iíll tell you the whole story.

All right you start. Tell me first about what you remember when you were a little boy. Tell me first about your mother and father.

I remember that I was since 3 Ĺ years and when my father died, I got left with my mother and two brothers.

What was your fatherís name?

My fatherís name was Icha (Itzak).

What kind of work did he do?

We had a little house-about 4 rooms and we had ground and we were working in the ground and we were making a living from it.

Was it a farm?

Little farm.

A little farm. Did he do any other kind of work?

Well, he used to go to buy stuff and sell it. He used to make a living.

You mean like a peddlar or blacksmith?

No he used to go to like to towns when people used to bring stuff and sell the stuff. He used to buy it and sell it and make a few dollars.

You mean at the marketplace?

At the marketplace.

Tell me what you remember about him.

Since the time I was working with my mother all the time. Helping her out.

You tell me what you remember about your father.

Thatís all that I remember about my father. I never remember my father.

You were telling me some stories about him. What stories were you telling me?

Well, I come to it.

OK

So, I know that people used to say that my father was very strong. Very strong. He wasnít afraid of 50 people. And, he had a father and mother. And they were living not very far from us.

Do you remember their names?

Yeah.

What were their names.

My grandfather was Rubin (Rieven). Rieven, they called him in Europe.

And your father--his names were Itzak ben Rieven. What kind of work did he do?

He had a saloon. A wholesale saloon. And my grandmotherís name was Leicha (Lya).

All right. Now you tell me more about your father. You said that he was very, very strong. You were telling me a story about...

One time he was going to his father and they just brought a big truck with 2 barrels of alcohol. They were supposed to take this off so there was in the place about 10 men. And the 10 men went to take off the 2 barrels of alcohol but it was very slow and my father just came and he took one on his shoulders and brought it in the cellar and then that wasnít enough, he went again and took the other barrel and put it in the cellar. And when he went down to lay it down, he broke a vein in his back. But he was so strong that he didnít feel this till a year. When a year passed, he started to get cold, he started shivering so my mother sent for a big doctor and the doctor came and he looked him over and he said that it was too late. He is all poisoned. Because the vein, the blood went out and poisoned the whole body and heís going to live about 3-4 days and heíd be dead.

And, what happened?

And thatís what it was.

Do you remember when that was?

I remember a little. Very little.

What was the date, do you know?

The date when he died? Easter. It was the second day of Easter. You know I got yahrzeit. The second day of Easter.

Thatís what I want to know. All right then, you also told me some other stories about he and his brother.

Listen, so I tell you. After this, I was helping my mother and I stayed with my mother until I was 14 years old. My father and his two friends, they were very strong people. When they come to a place, everybody was afraid and everybody was running from them.

What were their names? Do you know the friends?

One friendís name was Sura (?) Leib Schlanger.

He was a cousin, wasnít he?

He was a stranger. But the other man was the same name as my father, Icha Bier. They were 2 cousins. He was the cousin. And, when they come together, they knew that no one could start any fights. They were the 3 strongest men in the whole around 50 years around.

Here is one thing else that I want you to tell me. Do you remember the name of the town?

My town?

Your town.

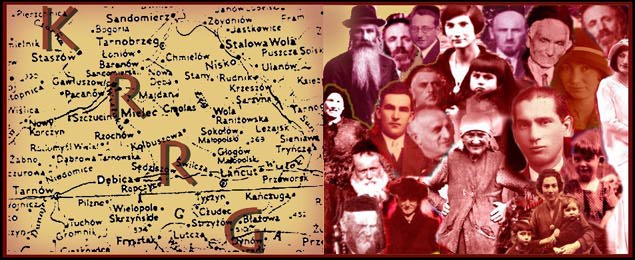

Sokołůw

Where was Sokołůw?

It was three miles from Rzeszůw. Rzeszůw was a big town.

Where is that?

In Austria. Austria-Poland.

That was the old Austria-Poland.

Thatís right.

Near Galicia?

Near Galicia. Yeah, it was Galicia.

With regard to Sokołůw, was it a big town?

My town where we were living was Trzeboś.

You mean after your father died?

No, no the same thing because

Sokołůw was a town and this was a village.I see, then you actually lived in the village.

Trzebo

ś (Chi bish!)by SokołůwNear Sokołůw

Near Sokołůw

All right. Was that a big village or a small village?.

Small.

About how many people do you think?

Oh, about three thousand people, thatís all.

How big was Sokołůw?

Sokołůw was big like that.

How big was Trzebo

ś?Trzebo

ś? Trzeboś was a town about three or four thousand people. It was like a village. Everybody had ground and were farmers, mostly.

Tell me about your mother. What was her name?

My motherís name was Geitalah Bier.

Geitalah.

Geitalah. My motherís name before she got married was Geitalah Tseitalbach. She came from a big farm about 6 miles away from my fatherís place.

Is this the same area of Trzebo

ś?The same area of Poland. You know, the same place. She was 6 miles away, one from the other.

Do you remember or do you know how old they were when they were married?

Oh, my father was about 22 years and my mother was about 18.

How old was your father when he died? Do you remember that?

Twenty eight years.

Was there anybody else in the family? Brothers or sisters?

Only two brothers.

What were the names of your brothers?

One was Meilech.

You were the oldest...

I was the oldest.

Meilech was the second brother?

The second and Leibisch was the third one.

Now, Meilech was your next youngest brother.

Yes.

How much older than he were you?

About a year and a half.

And how much younger was the little one?

Leibisch was another year and half or something like that and I was about a year and a half older. We were each about a year and a half.

What about Leibisch? You told me that he was a twin...

Yes, he was a twin.

What about the other twin?

The girl?

The girl...

She died when she was 18 months old.

Do you remember her name?

Fagin.

You donít remember what she died from...

No.

Now, you tell me what happened after your father died and before you went into the army.

Iíll tell you about that. When I was home and I was working, I was always thinking to go to America. I always was thinking to go to America.

Why was that?

Because everybody said America is very good. And when I was 14 years, now the story comes, listen! When I was 14 years of age, I said to my mother, "Mom, I canít stay home anymore. I would like to see and to come to something. I wonít work here and I wonít stay here." So my mother says, "what are you going to do?" So I told her that Iíll go to a big town and Iím going to see what I can do.

What were you doing up until this time? What kind of work were you doing?

On the farm--home. So, like every mother. She said, "all right, my kind [Yiddish-something to the effect of Ďall right, my child, if thatís what you want to do, itís O.K., go with luck and be well and donít forget about meí)" so I said goodbye and my mother gave me $10 and a little bundle with a little bread and butter, a piece of cheese and I was walking. So, I walked from one little place to the other and it took me about 8 days and I came to Przemysl [he pronounced it Premish but the correct pronunciation is PSHEH-mishl] a big town. It was a big town, a fancy town and when a little boy comes like that to a big town he first goes looking from one window to the other. So, I was looking in the windows and I came to a big, nice show window. There were all kinds of pictures. Pictures like Jesus and Mary. All Christian pictures. .religious pictures. And I looked at all the pictures. A man came out of the store, a nice man, nicely dressed and he said, "young man, you are a stranger here." I said yes, I just came in. He said, "do you like those pictures?" and I said, " yes, theyíre very nice." He said, "what are you going to do?" I said, "Iím looking for work--if I can get any work, Iím going to work." He said, "Iím going to make you rich. Iíll give you work and make you rich. Youíre going to have plenty of money." I said, "how?" He said, "come on in the store." So, I went in the store to look around. I saw that the store was full of pictures. He told me that he had boys and men who went around to peddle the pictures. He told me if I wanted to do the work, I would have a whole lot of money. So I asked him how to do it and he said that he would give me the pictures, put them on two straps on the back and go from one town to the other and from one house to the other and sell them. A picture will cost you 9 cents. You know, the pictures were oil pictures. He told me the other pictures that were the half size of it would cost 2 Ĺ cents. He said you can take for a picture a dollar, you can take a dollar and a half for one picture, you can take 75 cents--whatever you can get. But donít you think when you come in a house you sell one picture--you sell five or six pictures. And, thatís a whole lot of money! He said you donít need to rush, you donít have any bosses, you donít have nobody and you make money. He said youíre going to peddle around from now till fall and in the fall, youíll come home. Youíre going to see how much money you will make. When you come home, you stop in here and Iíll tell you how much business you made and youíre going to be all right. So, I said thatís going to be very good, but how will I get the pictures.

The man said, " when you come into a town and you see that you are low in pictures, drop me a postal to the next town youíre going to come in and Iíll send you the pictures by parcel mail. You go to the Post Office and you say that you have a package here, theyíll give you the package and youíll pay c and d [COD?] and take the package out and thatís yours and the money comes to me. You wonít owe me anything and I wonít owe you anything until you go home."

And thatís what I did. I bought myself a nice valise that fit on my back with two straps on my hands and I put in for $10 of pictures and I went. By foot I went. About two miles further up, I start to work and I worked and I sold a very good business. I used to sell to one house the woman came to the room and the daughter [?] and I used to sell 10, 15 pictures in one house and I made a very good business though the years. And the people didnít have any money but they had a whole lot linen, very fine linen and I used to take the linen and used to save that linen and used to sent it to my boss but he used to send me the pictures and he used to keep that linen for me till the time comes when I come back again before Easter to that man at the store and he took me around and he kissed me. I said that I was the best salesman they ever had. I made over a thousand dollar business. Do you know what it means a thousand dollar business? And he took me around and he gave me a very good time. I was with him for 3 days and I bought myself a beautiful suit, I bought a nice ring and I bought a watch and chain and I had about fifteen or sixteen hundred dollars with me alone that I made. So, I took the linen and I told him that he should send it home to my place and I got dressed nice and I went home. When I came home, everybody was running. They were thinking that I was dead! (Ooooh, I see). For six months I didnít write, I did nothing so that everybody was running to see me and see that I was dressed so well, I had a gold watch and chain, I had a ring on my finger, a beautiful ring...everybody started to ask me questions and I told them that I had been working and that I had a very good boss and the boss sent me home a big looking glass [mirror] from the top to the bottom for a present and it was very nice. Till the time after Easter, I said to my mother, I gave my mother a thousand dollars money when I came home and she told everybody I brought money, I brought a whole lot of linen and linen was very dear in our place--it was fine linen. She used to get a whole lot of money for that linen. She used to sell it by the yard--I used to get 5 yards, 10 yards, 15 yards in one strip. And after this, I said to my that now I was going again after Easter and Iím going away again. And we had a neighbor, a Jewish neighbor, his name was Yankel Greenfeld, and he was a man who had a son and that son was about my age and he used to go around with me and the father wanted me to take him along. And I said that I donít take anybody along. Iím going by myself, I work by myself and Iím going to work by myself. He said, "youíre going to be sorry." And I said, "why" and he said, "youíll see." So, I said to myself, all right.

So, I went by myself and I was gone all summer till fall and I made not so good as I had the first road. I took another road like to Hungarian and it wasnít so good, but I made money. I didnít make as much but I made plenty of money. I came home and my mother took me in the next room and she told me that we had trouble. I asked her what kind of trouble and she said you didnít take Mark (?)along so he now theyíre going to make you be a soldier. Theyíre going to report you that youíre going to America and you know how it is that in Europe they donít want to send boys to America.

Well, let me just straighten one thing out. Everyone was supposed to go in the Army then? Every boy was supposed to serve a certain amount of time in the army?

Three years.

Three years in the army. How old were you supposed to be when you were going to be taken?

Twenty. But you could enlist at 16, 17 or 18.

If they thought that you were running away, then they would try to catch you before?

Yeah.

I see.

So the gendarmes in Europe had noticed as soon as I came home that they should lock me up.

How did they find out?

He, that neighbor, went and reported that I was going to go to America as soon as I came home. So from the government, the gendarmes got notice that they should lock me up. But when I came home, my mother told me this but she said, " Iíll tell you--I was talking with the sergeant like the PostenfŁherer, they say because the gendarmes used to come in our place and they used to drink, and they used to eat and they used to sleep (they were friendly). They were very friendly and they didnít want me to get locked up. So, the Postenfuherer said to mother that the best thing to do, I wonít take him along, but tomorrow morning, let him go to the recruiting officer and let him report that he wants to be a soldier. Theyíll examine him but they wonít take him because heís too young--heís only 15 Ĺ years old, so theyíll send him home and heíll be free and nobody can say anything. So, I did this. The next morning I got up, got dressed and it was 3 miles to go to the bureau where you enlist. I went up there and I went in the office and I saw a soldier at a desk, a sergeant, and I told him that I came to enlist. He said, "all right, sit down." I sat down and in came a lieutenant and he sat down, too. And then in came a captain and sat down at the table. They told me I should take all my clothes off. So I took all my clothes off and the doctor examined me. There was a major, the captain was the doctor--he examined me and he saw that I was all right and he said all right. He told me to get dressed and they swore me in and they sent me right from there away to Tarnůw.

Well, what happened--I thought they werenít going to take you?

They took me right away.

They fooled you.

Yah!

They sent you right to...

Tarnůw.

Tarnůw--to the camp.

Yeah.

You didnít go home.

No.

They didnít give you a chance to go home.

I came to Tarnůw and I was a feltsjager #4.

What is a feltsjager? Is that a little officer?

No, no, no. Feltsjager, thatís the first in the war. Theyíre very, very snappy.

You mean theyíre a certain branch.

Just like here the Marines.

I see, the fancy branch.

Just like the Marines, very good soldiers.

What is the number again?

Jagers--feltjager.

What number?

Number 4. I was number 4 and when I came there, like every recruit...

Letís stop here for just a little bit because I want to go back and I want to find out some other things before we talk about your time when you were in the Army. Of course I know that you have a lot of stories about the Army you want to tell me.

Yeah, lotís of stories.

Weíll go back and speak of other things--about your brothers. Now your middle brotherís name was Meilech and the youngestís name was Leibisch. While you were in the Army, what were Meilech and Leibisch doing?

They were with my mother home, on the farm. They were working together.

They were both on the farm, working...

Thatís right.

And the same thing while you were out on the road selling. When you were selling pictures, they were still on the farm?

Yeah, sure.

Tell me a little bit about Meilech. He was married.

He was married but when I was already here in America.

Do you remember the name of his wife?

No, who can remember? I know she was one daughter of her parents (garbled??).

Did he have any children?

You know who his wife was? Iíll you who she was..you know Itzy Schlanger?? (Yah.) The one that has two sons, thatís his sister.

His sister--Itzy Schlangerís sister?

Thatís right. Thatís who he married.

Ok. Thatís fine. Did Meilech have any children?

No.

None, at all?

No.

You said something about Meilech coming here to this country--tell me about that.

He came. When he got married, he took over a big farm and he owed a big mortgage so he came to this country and he was staying with me and he had board with me and he ate with me and he was working and he made nice money. He made about $38 a week and he put every cent in his pocket and when he went home, he had about sixteen hundred dollars. He had about sixteen hundred dollars at the time. When I went home, I bought him a golden watch and chain for a present, I gave him a big ring with my initials that I had with initials and I gave him everything for a present to take home. He took it home and after when he was home, he never even wrote me a letter. Honest, he never even wrote me a letter.

Be nice. This was while you were living in Hoboken?

Yeah.

What else do you know about Meilech? Do you remember anything else?

You know when he was in my place?? When the twins were born--Jerry and Betty--because he used to play with them. I remember they were small, just like Janny and he was playing around with them.

[

probably around 1906 since my ( Mary Wilson) father was born in 1904 "litte Janny" was born in 1954 making him about 2 when the interview was conducted]All right, now, what have you heard about Meilech since then?

Nothing.

Is he alive now?

The first letter he wrote me when he came home was that he arrived home. Thatís all and after, I never heard again.

All right. Letís talk about Leibisch.

Leibisch, I didnít know him?

You never saw him after you left?

No, he was a small, little boy when I left, like little Janny, and I never saw him again.

Do you remember anything about his being married?

Yeah, he got married twice. The first time he got married, he didnít have any children.

Do you know the woman that he married the first time? Any idea of who she was?

No, he told me that they were very nice girls--both of them. The first one didnít have any children and they wanted them and she couldnít have any. They went to doctors. And then he married another girl, some cousin of hers, a very nice girl and then he had three children, I think, a boy and two girls, so Hitler killed the two--only one is left and she is in Palestine.

What is her name? Is that Esther?

Esther, Esther Malka.

And Esther Malka is married?

Yes, and she had 3 children.

Do you know the childrenís names?

No. Two girls and one boy.

Theyíre in Israel now?

Yeah.

All right. You went into the Army.

Oh, you're back again to the Army?

Weíre back on the Army.

All right when I came to the Army every soldier got trained and when I got trained, they sent me to school. And I went for 4 months to school.

What kind of school?

To Officerís School, you know, Officerís School. I went to school in Vienna. I was in Vienna for four months and when I came back, I came back with stripes. Three stripes--I came back to the Company.

You were a sergeant then?

Like a sergeant--a little bigger than a sergeant.

What was the name of it, do you remember?

Cadet. And I was with the Army about a year and they promoted--gave me a higher rank, like a second lieutenant, must be like a second lieutenant. And then, thatís all. I was a big shot.

All right, tell me some more about the Army. Where were you stationed?

First I was stationed in Tarnůw and then they sent me to Vienna for 4 months and then from Vienna I came back again and every year I made three maneuvers. Every year I made it--all 3 maneuvers.

How long were you in the Army?

Three years and nineteen days.

How many minutes?

I donít know this....

Where else were you stationed after that?

I came to the United States.

No, I mean where were you stationed in the Army--anyplace else?

No.

Tell me about some of those maneuvers--you told me some stories...

About Kaiser Franz Joseph?

Thatís right!

Well, the first maneuver we had--you know in Austria the language is mostly German and everything that you speak, you talk to an officer and you have to talk German because he cannot understand anything else, so, naturally, they picked me out to be a messenger from one place to send to the other place.

Why did they pick you?

Well, they picked me because I could talk German. And, I used to deliver the message like to Kaiser Franz Joseph and to his son because they were both on maneuvers. One on one side with white bands on their hats and the other plain. It was like Russia and Austria, something like that.

Two sides...

Two sides, but when Karl came to his father and said, "father, I donít like this like that. We donít know who is winning or losing. How is it to get a couple of shots with real guns, with real munitions?" So the Kaiser Franz Joseph looked at him and said, " my son, youíre never going to be a Kaiser." He called the big honest (the trumpeter?)--the trumpeter and he immediately stopped the maneuvers. And when he got home, he called him (Karl ?)into his office and the Kaiser said, "you donít have a heart and Iím sorry I canít give you the title of Kaiser. If you canít take your own children and kill them. You know when they come together and shoot one and the other and it kills one or the other and thatís your children. You canít be by other with them, he says, if you donít have children, you are like a dead one [confusing]. You canít go anywhere, you canít keep warm anywhere and they take everything away from you. And the son said, "Iím sorry, I didnít mean it, I didnít think on it, but if I will live long enough to get to be a Kaiser." So, he got killed.

Tell me about the time that you delivered the message to Franz Joseph--when you saw him.

When you come to him, you have to stop six steps before the Kaiser, you salute, he looks at you and he salutes you back and then he puts out his hand and that means that you have to give him what you have. So you go forwards and hand him the paper that you have--you keep it very safe so that no one can get it away because when you go there, there is somebody on the road that wants to catch and get the paper away from you. He reads this over, and on the other side, he signs that he received it and puts what ever [message] he wants and you have to take it back.

Where did you see him--in Vienna, or in a tent or on the field?

Oh, on the field. And in one week, I was about seven times saluting him.

How long did you stay in the Army?

Three years and 19 days.

And then you were discharged?

Yeah, I got discharged and I got my books and my papers and they asked me where I wanted to go and I told them I wanted to go to Vienna and it didnít cost me anything to come to Vienna.

Why did you want to go to Vienna?

Because I was thinking right away to go to Hamburg, to go to America.

Werenít you going home?

No, I didnít want to go home.

Why not?

Because, you know if a young man comes home from the Army, they want to give you right away shothunen [Yiddish - "matchmaker"] and they want you to get married and I didnít want that.

So you didnít see anybody at all? You didnít see your family?

No.

You went straight to Vienna and then where did you go?

To Hamburg.

And then?.....

In Hamburg, I bought myself a ticket.

From Hamburg you took the ship. Do you remember the name of the ship?

Sure--Victoria.

The Victoria. Where did the Victoria go? From Hamburg it went where?

To New York.

Did it stop anyplace? England?

No.

You didnít go to Liverpool?

No...to Liverpool? That was before--with a small, thatís what I was going to say, we come to Liverpool and from Liverpool we took the Victoria.

The Victoria left from Liverpool. And then how many days did it take you?

About eight days.

Eight days...

Eight days to come to New York. Oh, we had a wonderful time.

What kind of trip did you have? Were you in first class, second class....

First class.

First class? You were rich! The fellow with all the money!

You know when I came here, nobody came with me, I came myself, I didnít have any addresses and I found my uncle [garbled].

Thatís where you went first--to your uncle? What was your uncleís name?

Lieb Bier.

Where was he living then?

In (New York?)--yeah, New York. Suffolk Street. 131 Suffolk Street--I remember this all my life.

All right--and what did you do--did you move in with him?

The first time I came to my uncle, it was on a Friday, so he took me after the first supper I had, he took me to a room and he said, "come here my child, I want to tell you a nice story." So I went to the room and it was him and me in the room. He said he was going to tell me a little story but that I was to remember it all my life. In America [in Yiddish he says, "if you go, thereís no father, thereís no mother, thereís no sister, thereís no brother, thereís no uncle"] if youíre going to work, youíll be all right and everybody will like you but if you donít work, donít ask, no one will like you at all. Even, he said, for that supper that you just ate today with me, youíve got to pay me for it and from today on youíre going to pay $3 every week. So, I said "all right" and I asked him how much it was for the whole month and he said $12 so I said, "here, Uncle" and I took out money from my pocket and said, "here is the twelve dollars for a whole month you donít need to worry at all." It was nice.

How much money did you have when you came here?

I had in American money about $175 in my pocket. I had over a thousand dollars in Austrian money. I had it in the bank and I took it out when I left from Tarnůw to Hamburg.

What did you do here in the United States?

So, I paid him the board and I said "donít worry about it." And he said (my uncle), "now we got to think what to do--what are you going to do?" And I told him not to worry, I would do something. So he told me that he wanted me to be all right. So he said, "do you want to be a tailor?" So, I said that I would be a tailor as long as I could make money. He told me that I could make a whole lot of money. On a Sunday morning, he would leave the house maybe 5, maybe 6 oíclock and he came running by and said [garbled], "Kind, Iíve got a job for you." So we went to a big shop, the machines were working like anything and he said, "you see, there is a big boss and youíre going to pay him $10 and heíll learn you for a whole month and youíll be an apprentice and youíll make a whole lot of money. Thatís the best trade there ever is now." So, I said all right--I was a good boy and I took everything that somebody told me.

So I said, "all right--Iíve got to learn something." So, the boss told me, " you have to pay me $10 and you have to work four weeks and when you come out from my place, youíre going to get money." So, I sat down right away at a machine and by the end of the second day, I knew more than the people who had been working a year there. I took everything up so quick so the apprentice saw that I could make pockets, I could make collars--I could turn the collars out--and then they gave me sleeves to put together and then they gave me linings to put together and everything I saw, I did. So I was working two weeks and I came home and said to my uncle, "why should I work for that man? I gave him the $10 and Iím going to look for a job. And, Iíll get a job." So he said, "well, you said 4 weeks...." And I said, "what is the difference--so he got my $10."

So, Friday, I come and I see him and I said when we stopped work--we didnít work Saturday--we worked Friday and I said, "Mr. Wolf, I wonít come to work on Sunday." He said, "why?" And I said, "why I should I work for you for nothing. I gave you the $10 and I donít want to work anymore. Iíll get myself a job." He said, "why do you want a job somewhere else--get a job from me. Take a job from me and the third week, Iíll give you $2.

Two dollars for the whole week?

For the whole week--give me two dollars. So, I told him OK that I would take the $2 but first I want you to give me the money, right away, because I told him "I know if I work it, you wonít give me the money." He said, "Iíll give it." So, I told him all right and that I would take his word. On Friday, he gave me an envelope with $2 and I said, "now I quit." He said, " why do you want to quit now? Iíll give you $3." And I said, "$5." So, he talked to one of his partners and the partner told him to give me $5. And I told him I wanted the $5 first and he gave me the $5. So, I got $7 back again and it cost me $3 and I worked 4 weeks.

What was his name?

Wolf. So, after the 4th week, I left. I told him that I was going that I didnít want to work anymore there and I went to Broom Street, they used to call it a chuzzamach [Yiddish for pigmarket]. They need all the operators and all the tailors used to go to that place. It was near [?] Ritz Street. We used to get jobs and the bosses used to come and get the working men, whatever they needed--they used to get there. So, I remember like today, there was a high man there and he was looking around, looking around and he came to me and said, "are you an operator?" I said, "no, I know [?] Ishbanel Rosenfeld" and he said, "come with me." So I went with him--his name was Pesach, I remember like today, he took me in on Fifth Street, I donít remember the number but it was between Rivington and Stanton on a stoop and there was about 4 rooms there. In the front, he had one machine stand and he said, "youíre going to operate and youíre going to sew on the machine and Iím going to baste and Iíll put it in your hand and Iím going to make you an operator." And thatís what happened. He was a very nice man. He basted everything for me. He basted in the sleeves. Everything he basted and I used to sew it around. And I was working with him for about 6 weeks and I was a full operator. See, I was the head. So, he used to pay me $20/week. And he made me an operator, that Pesach, and I was working with him for 2 years.

When did you come to the United States?

I came on a Friday, 1888.

What month?

It was March. March, it must about the 8th or 9th.

What happened after that?

After we had a big blizzard.

That was the big blizzard of...

1888.

And that was when?

Three days before Purim.

Three days before Purim in Ď88.

Thatís right.

How old were you then?

I was going on 19.

You werenít 19 yet, you were 18 Ĺ. In March of 1888 you were 18 Ĺ years old.

Thatís right. And I was here for three years...........TAPE ENDS!

This booklet is dedicated to the memory of my grandfather, Julius Bier, with gratitude for the hardships he endured as a young man in an effort to seek a better life for himself in getting to this country. I am also grateful for the foresight my cousin, Gerald Frolow, had in sitting down and making this tape with Grandpa back in 1956 when it wasnít fashionable to do so. Our family will be long indebted to him for not allowing a large and significant portion of our familyís history to pass into eternity unnoticed.

October, 1997

Mary Bier Wilson

P.O. Box 777

Fellsmere, Florida

© Copyright 2017 Kolbuszowa Region Research Group. All rights reserved.

Compiled by Susana Leistner Bloch