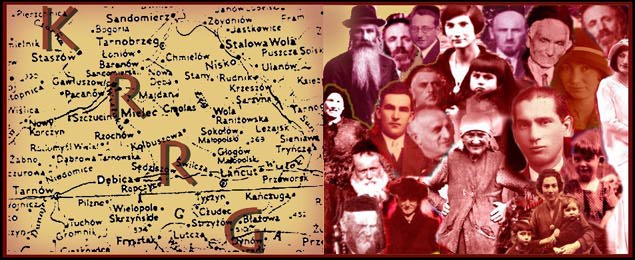

Norman Salsitz: How the Perished Community of Kolbuszowa was Saved

Norman Salsitz: How the Perished Community of Kolbuszowa was Saved

By David H. Lui

I met Norman Salsitz when I was 17 years old and in the time that has passed since then, I’ve discovered that with that meeting, I had fallen into the presence of the most interesting man I have ever met—in my 17 years before or the forty years since.

In the time I knew him, I was transformed from a high school student in Los Angeles who had a mild interest in history into a person driven to preserve the memory of the of the 1,700 Jews of Kolbuszowa, my family’s town-- all but nine of whom perished during the Second World War. And with him, my journey ultimately took me to Poland where a German film crew recorded Norman’s story ,as he searched the hiding places where the silver of the synagogue was buried, returned to his family home, and as he introduced me, his daughter and grandchildren to the lost Jews of Kolbuszowa-- meeting each family as if they were the characters leaping out of a story by Issac Bashevis Singer.

But how did I find and meet Norman? It was all happenstance. I wanted to know where my family was from. My great grandparents all came to the US in the 1880s, long before the holocaust. Long enough before the War for me to confidently say that “no one from my family died in the War.”

Yet I was always drawn to my history, and while my parents didn’t know the name of our shtetl in Poland, and my grandparents were dead, a Great Aunt remembered her father saying that his family came from “Culverseth—near Maden.”

But that made no sense—no index, no gazetteer, no matter how detailed, showed those two towns. But one day, my eye wondered across a map and I saw “Kolbuszowa,” next to another town, “Majdan.” How odd, I thought, that those two places should sound so similar to the name given to me by my aunt.

The year was 1977, and as I learned about those two towns, I found there was a Jewish organization from that town—A “landsmanschaft” or a social club where people born there would meet to talk, celebrate holidays, help each other-- and remember.

I went to a meeting of that group in Brooklyn where, one of the leaders of the organization, David Salz, confirmed that my family names were familiar—and he told me that the man I needed to speak to was Norman Salsitz-- one of the few survivors of the Jewish community of Kolbuszowa, and the only one willing to remember, and more importantly, willing to share.

Salz gave me a Kolbuszowa Yiskor book, which I still treasure, and on a family trip to New York, I took a trek on the Long Island Railroad and three buses to ultimately find myself at a strip mall in Springfield, New Jersey. After standing there for a minute or two, Norman drove up and asked if I was “David” and took me to his house.

If you ever saw the movie “Everything is Illuminated,” you’ll understand when I say that Norman’s house was the closest thing in the world to the house in the sunflower field, holding the remains of the mythical town of “Trechimbrod.” In his house in Springfield, New Jersey, the Jews of Kolbuszowa were still very much alive-- in the world of memory.

Every corner was filed with artificts, pictures, writings, rescued Judaica, and parcels being mailed, assembly line-like -- even 30 years after the war— to the righteous gentiles who had helped Norman escape and who still lived in Kolbuszowa under the Communist regime.

I didn’t know where to start.

Norman’s family had run Kolbuszowa’s general store. When the Nazis invaded, his father hid much of the merchandise with friendly peasant families, saying that if a member of the Salsitz family ever returned, they would have to give that person half of what had been hidden. And even then, sometimes that half could only be reclaimed by showing a pistol. Using those goods, Norman—Naftali Saleschutz, as he was known then-- escaped from the Kolbuszowa ghetto and was able to fight for four years from the nearby forests. Saving as many Jews from the town that he could—although many were ultimately killed-- and seeking retribution for those who killed his mother, father, five sisters, and their families. Before the movie “Defiance” was ever filmed, Naftali’s story was the story of defiance.

The Pictures. The most remarkable thing was that Norman saved thousands of pictures of the town before the war—and he still had them. Letters too.

The reason why he was not sent to Belzec with the rest of the Jews of Kolbuszowa was that the Germans pulled him, and a number of other young men, out of the line of people being deported demanding that they work to break down the dwelling places of the Jews—furniture here—pots and pans there—clothes piled there…

But trampled among the chaos left behind in each house were the family photo albums of the town’s Jewish families. Naftali stacked the goods as the Germans instructed, but each time he came across a photo album, he would take the pictures out and shove them the breast pocket of his leather jacket. Each night, he would hide them in the thatched roofs of the peasant farmhouses—each time, three large tiles from the bottom, and two tiles from the corner.

The Saleschutz family had an unusually close relationship with the farmers who lived around Kolbuszowa, as the Polish farmers routinely bought, sold and bartered dry goods that were in the family’s store. Because his relationship with the local farmers was strong, the Germans took advantage of this relationship and compelled Naftali to collect goods they needed from the farmers. This gave Norman the ability to hide the pictures outside the Ghetto.

Further, even though it was unusual for a boy from a small town in Poland, Naftali had his own Kodak Brownie camera that he had received as a Bar mitzvah present in 1933. Since his father was a merchant, film was always available as he went around town snapping pictures. He hid these pictures in the farmhouses too.

“When the people of Kolbuszowa come back, I’ll be a hero,” thought the 17 year old Naftali. But, of course, the Jews of Kolbuszowa never came back.

After the War, he retrieved the pictures, but as it became clear that no one would return from the “East,” he safeguarded the pictures himself. The pictures traveled with him for the rest of his life, through Europe and finally to America, ultimately landing in his small corner of Kolbuszowa in Springfield, New Jersey.

He never had the opportunity to be the hero of the perished families-- who I came to know through the pictures as smiling figures, posing on sunny days for their photo, proudly standing by the synagogue, tending their stores, doing the wash, or standing in front of the houses where they lived. While Norman couldn’t be their hero-- as he explained the photos to me, he quickly became mine, because he remembered everything.

The pictures were a window into the past. He’d pick one up: four smiling girls sitting on a fallen log, with their legs on either side as if they were on a horse. He’d start by telling me their names—their schools, how their families were related, and then their stories. “This was killed by the Nazis during the invasion, that one was killed by the girl who’s sitting behind her—He’d tell me the details, and that the girl who killed her was a Gentile, a friend until the Germans came, the third one was killed by the AK, the Polish underground which would hunt Germans by night and Jews by day.

We discussed picture after picture after picture.

It didn’t take me too long to know that I needed to video tape his discussions and that effort sent me on a 30 year odyssey of making pilgrimages to New Jersey, carrying bags of computer scanning equipment and generating scores of hours of video. He narrated each picture and the clips of film that still existed of the Jews in Kolbuszowa in the 1920s.

But more importantly, he remembered how everybody was related to one another—and all the sudden, my thoroughly American family, when I went back two additional generations, blossomed into a family tree of 1,300 Kolbuszowa Jews, and to my shock, I learned that I had more than 300 cousins who died during the War. I was dumbfounded.

The Forest. Naftali didn’t just survive the War: he fought. God help me the night I made the mistake of saying he “hid” in the forest. He told me in no uncertain terms: He fought. He killed as many Germans as he could, he was a Partisan-- and taught me to stand when the Partisan song was played. To him, it was the pre-statehood national anthem for the Jewish people. He got a pistol and wasted no time taking revenge against the Poles that killed his father in front of him. Those were, in fact, his father’s last words when he was shot: “Take revenge.”

But Norman also taught me to love the righteous gentiles: the Priest of the town who gave him papers to “pass” as a gentile, whose gravestone he lovingly prayed at when we returned to Poland. The Polish family that allowed him to live in their farmhouse: people who risked their lives for him, and people who he ensured were awarded honors as righteous gentiles by Yad Vashem, because Norman would not stop until they were recognized for the good they did.

And after Kolbuszowa was liberated and the full extent of the horror was clear, Norman, now a Polish Officer, reaped the whirlwind. He personally went to convents to reclaim Jewish children who had been hidden—forcibly taking them and turning them over to the representatives of the Haganah who were collecting survivors for the arduous trek over the alps to Palestine, and then returning to the Army, to fight his way into Krakow.

Krakow. Once his unit entered Krakow, it became clear that the Nazis had wired the city for destruction. “Mines” or huge bombs were planted throughout the city, and all the wires lead to the offices of a German engineering company.

Norman ran along the line of the wires, following them back to an imposing office building, pausing for a moment for his comrades to catch up with him. Then together, they cocked their machine pistols and burst into the offices, where they were confronted by a beautiful young blond receptionist, calmly sitting at a desk, where the wires all came together at a lever which was next to her hand.

“I’ve been expecting you,” she said. “The Germans are all gone,” she said in perfect Polish.

Now with six guns trained on her, a mere squeeze of the trigger standing between her and certain death, Norman firmly said, “Don’t move your hands, but get up and move away from the desk.”

And with that, she slowly raised herself from her chair and explained, “the SS Oberstormgruppenfuhrer called me with the order to blow the mines five hours ago. I took the call and assured him that it would be done. I told no one that the call had come, and when the others left they instructed me to stay here as long as I could, in case the call finally came. They had no idea it already had come and I had ignored it.”

Now she was standing, her high heeled shoes together, her hands clasped in front of her waist-length jacket. “I waited here for you to be sure that no one else pulled the lever.”

Knowing that she worked for the Nazis, Norman didn’t believe her, and questioned her for hours on end. But as time went on, and his true identify became clearer to her, she allowed her identity to become clearer to him. She was Jewish. Hiding in plain sight for years, she revealed herself to him, and he protected her.

And every time I went to New Jersey, she would answer the door for me, feed me dinner and prepare a bed for me as I talked to Norman about his pictures late into the night. She and Norman were married in Poland and she remained his wife for 50 years.

Returning to Kolbuszowa. But while she was alive, I could never get Norman to do the one thing I really wanted: “Naftali, take me to Kolbuszowa,” I pleaded.

“I cannot do that. All Poland is a big cemetery, and as a Kohan, I cannot enter!” But while he wouldn’t go, nothing could stop me, and he prepared me for my trip. We looked at the modern pictures I could find, and he explained what each building was, who owned it, the names of the streets, the nature of the businesses—Jewish and non-Jewish, and the noteworthy things that happened in the town. By the time I went in 1995, I was an expert. I knew what I was looking at, and what I was looking for.

But it was a very strange experience: while my knowledge was all very precise, it all dated from 1942. The young people would look at me and cock their heads as I spoke through my translator—but the older people would listen to me and make the sign of the cross across their chest, wondering how I knew the things I did.

As time passed and life went on, Norman wrote three books on Kolbuszowa. One more interesting than the next, and not just about the War either—about Jewish life before the War too. Against all Odds, was his first book, an elaboration of the fascinating stories in the Yiskor book. His second book, A Jewish Boyhood in Poland, is in many ways my favorite book, because it gives a wonderful insight into the life of the Jews of Kolbuszowa before the War, before that way of life was destroyed. You can clearly see the thread that joined their life to our lives as modern Jews. His final book, Three Homelands, is a series of vignettes regarding his experiences during the War, but after the War too, and the difficulties of transition.

Norman and his Family Return to Poland. Years passed, and in about 2003, Norman’s wife died. I had a son in the intervening years, and one day—out of the blue, Norman called me. “I’m going back to Kolbuszowa with my daughter Esther and my grandchildren in two weeks. If you want join me, you can come.” It turned out that his story had been picked up by a German film maker, and the movie, “Coffee Beans for a Life” was to focus on Norman’s story.

I had a new Job and a new baby. My wife and I had just moved to our first house. But this was the moment my journey with Norman had taken me to. I had to go.

We flew in Warsaw and drove to Kolbuszowa. As we neared the town, we drove down country roads, and my video camera was always trained on Norman as he shared his memories. At one point, Norman looked out to the forests on either side of the small secondary road near Kolbuszowa.

“This was near the partition line with the Russians,” he said. “The last time I was on this road, the munitions were stacked here in huge boxes and artillery pieces towered 20 feet over my head. Everything was covered with camouflage netting and Nazi guards positioned every 50 feet, each with a motorcycle nearby. The invasion of Russia started the next week, I was passing through on a horsecart selling goods from our store.”

I could see the reflection of the German soldiers in his eyes and I was with him. But it was not 2004, it was 1941. We were quiet after that until the car reached Kolbuszowa.

And once we were there, we wondered through the cemetery which contained the mass grave where Norman had buried his father. We dug into the cellar of this family’s home in the Ghetto, with representatives of the Polish State Museum, where Norman had buried the silver and torahs from the synagogue, but we found nothing. We said prayers over graves that had been abandoned for decades, and he confronted the people who had let his family die. He showed us where he grew up and we visited his house, saw his room and the room and school of his favorite sister, a beautiful young woman named Rachael whose face I knew well because her picture still hung in his house.

Rachael’s story was particularly sad, and Norman was always the most sad when he discussed her. She was four years older than Norman, and just before the War, she was engaged to be married. She and her betrothed both applied for visas to leave Poland as it became clearer that clouds were gathering on the horizon. Her visa was granted, but her fiancée’s visa was stalled. Time passed, and her permission to leave lapsed. Then, unexpectedly, her fiancée’s visa application was approved and he received permission to emigrate. When his papers were approved, he left without her. He survived the War and she was killed at Belzec. It is a story that can make me sit somberly whenever I tell it.

The most moving moment of the trip was in the synagogue of Kolbuszowa, a building which had been slated to be a museum of firefighting as there were no Jews left in Kolbuszowa. In spite of the “important” theme, the new museum had never really gelled, and synagogue building remained vacant and unused—probably a more fitting memorial to the Jews who had prayed there for centuries before they had been murdered.

Norman brought the German film crew, his daughter, and grandchildren into the building which had not been a site of Jewish prayer since 1942, and proceeded to sing a benediction and blessing over his family. Standing there, just out of sight of the cameras, I stood as the beautiful sound of his voice began to reverberate through the building which—while designed for the sound—had lost its voice.

I was overcome by the power of the sound and the moment, and the only thought, racing through my head was that I couldn’t let the camera pick up the sound of my emotion, as nothing could be allowed to detract from the beauty of that moment. I don’t know where Survivors can find the strength to do what they do. Perhaps, in the broader sense, that’s why those few were selected to survive by God. I, on the other hand, almost bit through my lip.

Going to Belzec. During that trip, we went to Belzec, where the Kolbuzower Jews who survived the massacre at the Glogow forest were all killed. We pondered the 40-foot tall pile of pumice which, from a distance looked like a hill, but as we came closer, we came to understand that it was the hardened ashes and remains of over a million Jews of the General Government, including the Jews of Kolbuszowa, and Norman’s favorite sister, Rachael.

Something happened to me at Belzec that I remember as though it was in a dream. For that visit to Belzec, I had brought a very large Israeli flag with me. The day we arrived at the Belzec memorial was the day the memorial opened to the public and I wanted a flag to represent the people killed. The Polish government sponsored a huge gathering and thousands of people, including a large number of American Jews were in attendance. The Israeli government sent a military delegation.

I had brought telescoping aluminium poles with me and constructed the flag and poles on the bus, but as I did it, my hand slipped and I cut my thumb. Not a big cut, but deep. It took about 20 minutes for it to stop bleeding. When I got off the bus, there was a strong wind, and all of us gathered around the flag, which whipped as I struggled to hold it straight.

A moment came where the wind died, and the flag stopped waiving, and as it drooped, it crossed my face, following the line of my arm, and started to waive in another direction. When I looked up at the flag, I saw a huge red stripe across it. I was confused. My eye followed the stripe to my arm, which was covered in blood. The cut on my thumb had opened up again and I was bleeding profusely.

I quickly rolled up the flag and ran to a first aid station where they gave me a bandage and helped me clean my clothes. But walking back, people had moved away from path I had taken to get first aid. All looked at the ground in disbelief. No one could understand why the fresh yellow concrete of the new memorial was splattered with drops of bright red blood.

It was on this trip that I learned about the rest of Norman’s story. In the years I had known him, I had only asked about Kolbuszowa. He told me about Krakow too. But I never knew that he was at Auschwitz within two days of the liberation.

“The ruins of the crematoria were still smoking,” he said as he described the horrors he saw. He went on to liberate Silesia, and expel the Germans from Breslow, as the treaties which ended the War had mandated the annexation of that region to Poland from Germany. When he told the story, the German Film producer who was with us said, “My family lived in Breslow—we had to leave when I was three years old and carry only what we could.” Circles within circles defined this story.

But while I was very unresolved in my attitudes toward the Poles and Germans, I learned from that trip not to hate the generations who followed the generation of the War. I watched, and learned, as the German producer showed her profound regard for Norman, and while Norman flirted with the young Polish women on the production staff. I learned to reserve my disdain for the perpetrators and not for their grandchildren.

After the War, Norman wanted to go to Israel, but his family there begged him to go to the US. “Here, you will just be another mouth to feed. There, you can help us, and send money which we need to survive.”

So Norman came to the U.S. He built houses and became rich. But always loved Israel. His pictures of the first Yom Ha’atzmaut parades in 1950, were almost as interesting as his pictures of Kolbuszowa. At some point, I decided that I’d need another life just to analyze how he spent his life. The walls of his den were filled with various plaques recognizing his commitment to Israel. If he was out of the room, I was lost in the treasures on the wall—Ben Gurion, Golda, Begin. They were all there.

But the thing I loved most about Norman was his sense of humor. For all the horror he lived through, and all the pain he suffered, he never forgot how to laugh. I often think that this simple thing was his greatest accomplishment.

Return From Poland. When we returned from Poland, I had one of the strangest moments of my life.

It was a few days before Kol Nidre, about two months after my visit to Kolbuszowa with Norman. I found myself in Redwood City, California, where I went one of the few stores in the country which specializes in the sale of Israeli Stamps. My Grandmother had started the collection for me and from time to time, I would update the set—mostly to remember her.

But I will never be able to explain the thing that happened next. The store was—how can one say kindly-- not well organized to the “untrained” eye. Stacks of ephemera, old abandoned stamp albums of collectors who had long been dead, old newspapers, and First Day of Issue stamps were in heaps from floor to ceiling. But I saw a group of notebooks that looked different. I don’t know why they caught my eye. They were unmarked—but not “of a piece” with everything else.

“What are those?” I asked.

“They’re wartime cancellations from Jewish ghettos,” said the shop-keeper.

I asked to see them. All the big cities were represented: Warsaw, Lodz, Danzig. But there were smaller towns too—lots of them.

“Does one of the books have cancellations for towns that start with a K?”

He handed me another notebook, which I opened and leafed through. Then, I saw it, “Kolbuszowa.” When I opened the book to that page, there were only two items, and I knew what they were immediately. I recognized both the addresses of the sender and recipient and my eyes slowly filled with tears. They were postcards, written in microscript, stamped by a half dozen Nazi censors from Norman’s sister Rachael to her Fiancée in America. It was sent after the German invasion of Poland in 1939 but before the United States entered the War, and before Rachael was killed at Belzec.

They had been sold after Rachael’s fiancée’s death by his family for the value of the unusual Nazi stamps, and the strange and rare cancellations.

The next time I saw Norman, we labored late into the night with a Sherlock Holmes-sized magnifying glass to translate the Yiddish. Finding that card is one of the strangest things that ever happened to me. How can you try to explain the odds of that? In the most profound sense, you can only say that they are astronomical.

Portscript. Norman died in 2005, when my son, Yonatan, was seven. We treasure the few pictures we have of Norman and Yoni together. Yoni only met him twice, and Norman gave him a small porcelain figure of a dog from his desk, which is still in Yoni’s room. But Norman’s memories of Europe, and my reverence for him, and Yoni’s early understanding of how the Jews were unable to protect themselves, all made their mark on my son. Norman’s daughter and I have remained close. That connection to him gives me great comfort.

My son is now a year older than I was when I met Norman. A generation has passed. This summer, he will be joining Garin Tzbar to become a lone soldier in the Israel Defense Forces. While I have been an active pro-Israel advocate for years, the army and emigration to Israel were never on my screen as a high school student in California.

But somehow, the bus ride I took to New Jersey, and the many pilgrimages I took afterward, sent my family down a different path-- a path inextricably linked with the fate of the Jews of Kolbuszowa.

Yoni will start his service in August and intends to stay in Israel. He swears that he will have a child named for Norman, an “N” for Naftali. Adding that name to the other Kolbuszower Jews on my family tree will be especially meaningful to me.

© Copyright 2017 Kolbuszowa Region Research Group. All rights reserved.

Back to Kolbuszowa Shtetl Page | Back to KRRG Travelogue Page