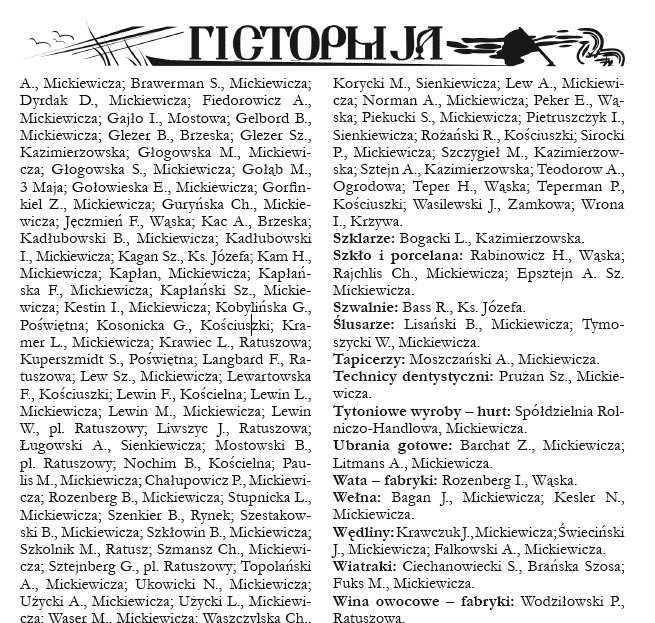

Fig. 4

In figure 4 - Zipora

Barchat, the founder of the Manufaktura and Ubrania

Gotowe. Also appears in the 1928 Bielsk's Business

Directory taken from p.55 Bielski Hostinec Journal 1 2010

(fig. 5).

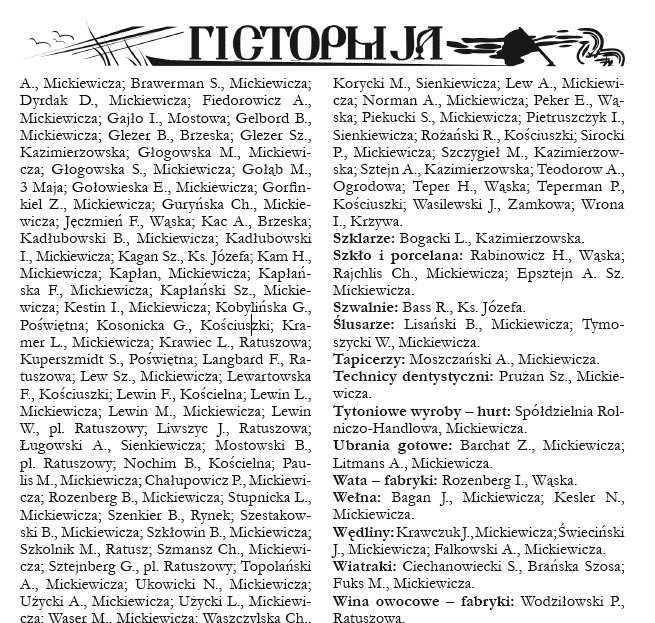

Fig. 5

The Barchat's business did

well and all three brothers lived a comfortable life. They

had a huge garden at the back of the house, planted with

flowers and orange trees. Two German- Shepherd dogs tied

with metal chains patrolled their garden. New toilets were

built in the garden as well as storerooms for their

merchandise. The Barchat's could afford 24 hour help in

the house. The help took care of the daily domestic tasks

such as cleaning, carrying water to the house, preparing

the laundry and ironing.

The children often went to the theatre

especially in Bialystok. The family used to travel a few

times a year to Druzgiennik, a resort area, for a holiday.

They rented a house in the woods for a couple of weeks and

enjoyed the wooded surroundings.

In figures 6 and 7 - Izaak Barchat with friends in Bielsk.

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

In figure 8 - from right to

left: Feigel and her husband Natan Barchat with their son

Izaak, Nechama and her husband Israel Barchat with their

son Janek. Far left: Jacob Barchat, Izaak's older brother.

Fig. 8

The only family member

who was very religious was my great grandpa – Natan.

Natan used to go to the nearby Synagogue and was very

active, providing concealed donations. He used to buy

firewood and deliver it confidentially to needy

families. In his later life in Israel he founded a

voluntary association named "Yad Achim" (literally

giving a hand to all brothers) to help the needed

ones. The rest of the family was not as religious and

did not dress as typical religious Jews.

Fig.9

In figure 9 - Natan Barchat in Israel in the 1950's

with his granddaughter Irit Barchat.

All three brothers were ardent Zionists. The family

helped financially and actively with many Jewish Youth

groups in order to make "Aliya" to "Eretz Israel",

which was still Palestine at that time. They insisted

that their children speak and learn in Hebrew

institutes. Few of their children travelled to nearby

Bialystok to study in the Hebrew Gimnazuim. Izaak, my

grandfather and his sister Halina studied in Bielsk at

the Polish Gimnazium. Halina wanted to study Medicine

in Warsaw but was refused because she was a Jew. She

then decided to study Economics and graduated in 1939.

Chaim and Israel traveled back and forth to Palestine

in 1933 and even earlier. Their plan was to sell the

house and store and move to settle in Palestine. They

were both in Palestine when things turned for the

worst in Bielsk Podlaski. Chaim's wife and daughter

had the good fortune to join Chaim during a holiday

visit.

In figure 10 - Chaim Barchat

Fig. 10

Deportation

In 1939 The Germans signed a nonaggression treaty with

the Soviets which resulted in turning Bielsk to a

Soviet territory. Under Russian rule, Natan and his

family and Nechama with her children were forced out

of their big house. The Barchat's suspected this was

coming and so began packing their personal belongings.

They were taken to another part of Bielsk on a shaky

horse and wagon, losing bits and pieces from their

possessions on the way. The Barchats moved to live in

one room in a house which belonged to a kind Christian

Polish woman. They were there for a long while, more

than a year.

Between 1939 and June 1941 about half a million polish

citizens who were accused of being capitalists i.e.,

citizens with high social status, members of the

intelligentsia and good education were deported to

labour camps in various parts of Siberia and

Kazakhstan.

On the 20th of June 1941, two days before the Germans

entered Bielsk, the Barchat family was deported on the

last of three big deportations of Polish citizens to

the Altai, the high mountains, in Siberia, near the

border with Mongolia and China. They were forced to

leave on a long train which consisted up to a hundred

freight cars and three locomotives on a journey that

lasted 3 weeks with several stops on the way. The

destination was far, unknown and the future seemed

darker than ever. Feigel Barchat was looking for a way

to save her daughter Halina. She found a Polish family

that agreed to accommodate her daughter for money and

gold until Halina would find a way to travel to a

distant family relative who lived in Moscow. Halina

did not want to leave her family but her mother

insisted, thinking it was the only chance for her to

survive. The decision turned out to be a tragic

one. Halina was killed. No one in the family until

today knows the circumstances of this painful event.

Upon entering the train in Bielsk, the names of the

passengers were called out loud from lists. Sima,

Nechama's daughter, turned out to be missing from the

list. Her mother did not think twice. She told her

daughter to depart immediately from the train in order

to save herself. Sima was crying because she was

frightened to leave her family. Her mother pushed her

off the train. Sima fell and the train took off

leaving her behind. Sima was shot soon after. Similar

to her cousin, Halina, no one knew the circumstances

surrounded her death.

Both girls had mothers who only wanted to save their

beloved daughters. Both mothers (who were also

sisters) blamed themselves for the tragic end of their

daughters for the rest of their lives.

On the train, together with the Barchat family was

another Jewish family named Frejdkies. The Frejdkies

were textile merchants who owned a store on the same

street as the Barchats. The rest of the families were

all Polish.

New life in Siberia

The train journey ended at the last stop in the middle

of nowhere. The family arrived in Siberia. Before

embarking on this journey, my great grandmother,

Feigel insisted on bringing her feather duvet from

home. This specially warm duvet was a life saver once

they reached the cold weather of Siberia. I am proud

to say that this particular duvet made it all the way

to Israel and is still being used today in my home.

The families were taken on horses and wagons. No

trains nor cars could reach the distant agricultural

labour camps called "Sovkhoz". The days were already

days of war and all the Russian men were drafted to

the army. The Sovkhoz were short on laborers so the

new labour shipments from Poland came in handy. The

labour camps had no fence. Despite the lack of fences

no one escaped. There was so much snow around that one

could not walk far. The family was separated. Nechama

and her children were placed in a room with a kitchen,

sharing it with a Polish family. They were placed in a

village named "Soloneshnoe" (according to Igor

Zakrzewski memoirs). Natan and his family were placed

elsewhere.

The new workers received short training and soon after

were all sent to work in outdoor farming. One of the

Barchats daughters remembers how she was told to cut

tangled bushes that grew in the high mountains. It was

a hard job for a 16 year old girl who never worked

physically in her life, so her mother bribed the

officer in charge by giving him women dresses and soon

her daughter got a better job. She was collecting the

branches that were cut by others. Grandfather Izaak

had a Polish driving license so he ended up driving a

tractor plowing and sowing the fields. Many people did

not survive working hard in the freezing weather

conditions.

The shortage of food was acute but there were many

cows and horses in the surrounding fields. The workers

found a way of getting food. They used to tie the

front legs of a horse and push him into the

fast-moving water stream. The horse would lose

his balance, be swept down the stream, and be

killed. Then they would have horse meat at their

meals. They also had another method. There were

fields in which a poisonous weed (for cows only) grew.

The workers would drive a cow into those specific

fields, have her eat and when it died they would have

meat. Natan Barchat was the only one who did not touch

this non-kosher food but he was clever enough to

overlook when the rest of the family sat down to eat.

When the Sikorski –Mayski agreement was signed between

the Soviet Union and Poland in 30 July 1941, all

Polish citizens were allowed to leave the "Sovkhoz"

and move to nearby Biysk. Biysk was a relatively small

city but grew quickly due to the amount of wealthy

educated immigrants. Theatres and cinemas were

established and the place became a lively place. The

Barchats were united again. They found a room to live

in and the first thing they did was to send a telegram

to Israel Barchat who was in Palestine at the time and

soon after that, they began receiving parcels from

him. They traded the goods they received from him in

order to survive financially. Rose and Ada joined the

public school and finished their studies. Rose even

went on to study higher education. Janek worked as a

driver. Natan, being the religious one, soon found

himself socializing with other Jews and praying in a

local synagogue. The family spent 5 long years in

Biysk.

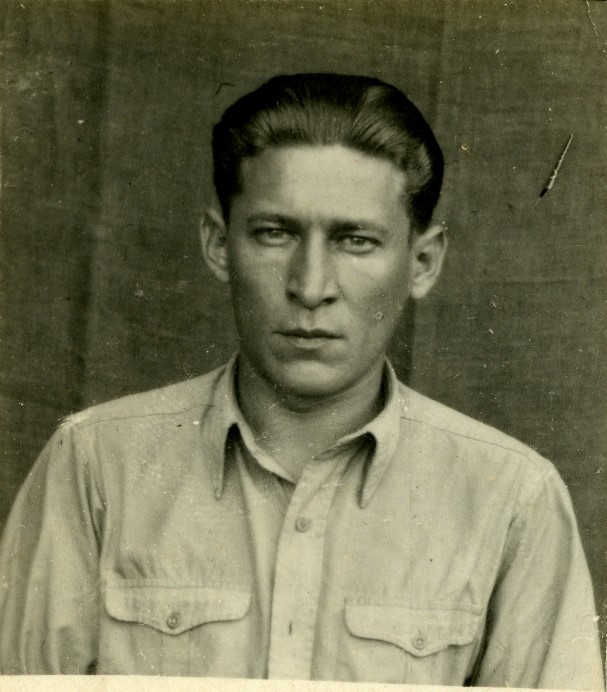

In figure 11 - Janek Barchat

Fig. 11

Epilogue

In 1945, when the war was over, the family was finally

able to begin their journey to Palestine to join the

rest of the family. Israel Barchat was working hard on

getting certificates for them to arrive legally to

Palestine (back then our country was ruled by the

British). They finally managed. The journey took them

through Poland. Natan and his family made a long stop

in Szczecin for almost a year waiting to receive the

certificates to enter Palestine from the British

Embassy in Warsaw. Nechama and her children received

their certificates in 1946 and managed to travel to

Marseille in France and boarded the ship to reunite

with their husband and father – Israel. In 1947 Natan

and his family arrived in Tel- Aviv (Palestine).

The three brothers settled with their families in Tel

Aviv not far from each other keeping close family ties

with one another. Today, my family tree consists of 50

grandchildren and great-grandchildren who are direct

descendants of those three Barchat brothers.

I would like to conclude my article by emphasizing the

meaning of my family's surname.

The Barchat surname is believed to be adopted, as with

many other Jewish and non-Jewish families, in the

1840s following new government rules. The name Barchat

means velvet in Russian which characterizes the

family's trade and business at the time.

Nowadays, the descendants of the Barchat family have

only girls and as hard as it is for me to admit, soon

the Barchat surname will no longer exist. As a

descendant to this remarkable family I feel that it is

my mission to strive to preserve the memory and the

name of the Barchat family as part of the rich legacy

of Bielsk's Jewish community.

Michal Itzhaki

Kochav-Yair, ISRAEL

February 2011