The Jewish Community of Zurawno from its Beginnings to 1919

Source: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities in Poland, Volume II, Eastern Galicia; Yad Vashem 1980

(continued from home page...) An organized community with various institutions already existed in the eighteenth century and the Jewish population continued to grow. Prior to WWI, the W. Kessler Foundation supported the old-age home. A certain amount of this institution's budget was set aside for hachnasat kalah to cover wedding and other expenses for one poor bride a year. After the First World War and the death of the foundation's trustees, the institution was supported by the va'ad hakehila (community council). Before WWI, a bank was established in Zurawno, which provided credit to those in need, especially small tradesmen. After its transfer to the va'ad hakehila, the bank stopped operating for all practical purposes.

Several famous rabbis served in Zurawno, among them Rabbi Moshe Shaul son of Rabbi Yehuda Leib (who was the town's rabbi during the second half of the eighteenth century and died in 1759). He was followed by Rabbi Yehuda Leib, son of Rabbi Moshe, the author of Shevet MeYehuda. More...

Several famous rabbis served in Zurawno, among them Rabbi Moshe Shaul son of Rabbi Yehuda Leib (who was the town's rabbi during the second half of the eighteenth century and died in 1759). He was followed by Rabbi Yehuda Leib, son of Rabbi Moshe, the author of Shevet MeYehuda. More...

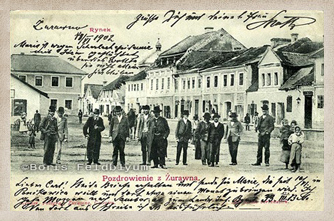

Postcard image courtesy of www.judaica.cz, permission granted March 7, 2010.

Visiting the Streets of Our Ancestors

Zurawno looks very much the same today as it did at the turn of the last century, when our families met and socialized in the town square, and this postcard image of Zurawno was produced. While many of the buildings were damaged during World War I and presumably rebuilt, the turreted roof in the center of the postcard image also can be seen in the background of the recent photo taken in 2003. Please visit the photo galleries to view larger versions of these images. Click to view a transcription and translation of the postcard text.

Postcard image courtesy of © Boris Feldblyum Collection, permission granted on March 23, 2010.

Occupations in Zurawno

The Ksiega Adresowa Polski 1929, "Polish Business Directory" provides a snapshot of what our ancestors did for a living. Occupations included carpenter, leather goods, watchmaker, hairdresser, tailor, tinsmith, baker, butcher, soft goods and sundries, bookbinder, grain merchant, lawyer, doctor and midwife.

The 1891 Galicia Business Directory's listings for Zurawno's Jewish residents included cattle dealer, tapestries dealer, fashion accessories and toy dealer, grocery store owner, textiles and notions, soap and candle maker, metalware dealer, and wood dealer.

Polish-Ottoman War Ended in Zurawno

The Polish-Ottoman War (1672-1676) was a war between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire, as part of the Great Turkish War. It ended in 1676 with the Treaty of Zurawno and the Commonwealth ceding control of most of its Ukraine territories to the Empire. More...

World War I and the Battle of Galicia

World War I and the Battle of Galicia

The Battle of Galicia was a major battle between Russia and Austria-Hungary during the early stages of World War I in 1914. In the course of the battle, the Austro-Hungarian armies were severely defeated and forced out of Galicia, while the Russians captured Lemberg and, for approximately nine months, ruled Eastern Galicia. More...

During the Galician campaign, the Austro-German army chose a site near Zurawno for a major offensive against the Russian forces. Even though it was not on a railroad line, it was selected because it was between the marshes of the upper Dniester and the impassable gorge of the lower Dniester. The conflict ended quickly due to the difficulty in conveying guns and ammunition across the deep river and slippery banks, and as a result the Austro-German army was forced to retreat to the south side of the valley. More...

A Brief History of Lvov, the Capital of Galicia

Lvov was the capital of Galicia. “Lvov” is the English name of the city. The city has undergone several name changes. In the 14th century, only a century after Prince Danylo of Galicia founded the city, Polish conquerors changed the name to “Lwow.” When the Austro-Hungarian Empire conquered the area in 1772, they changed the name from “Lwow” to “Lemberg.” It is now known as “Lviv" in western Ukraine.

Lvov was also the capital of Jewish Galicia, and many Jews of the surrounding shtetlach—like Zhuravno—came there for education, shopping, and religious training. The presence of Jews in Lvov dates back to the Tenth Century. There were two communities: one in the city and another outside the city walls. Though they shared a cemetery, they had distinct synagogues and mikvahs. The synagogue within the city walls was built in a gothic style in 1571. Rabbi Yitzhak ben Nahman and his descendants led the congregation for a hundred years. The second was built outside the walls in 1632. Both were destroyed in WWII. There were nearly a thousand Jews in Lvov by the mid-Sixteenth Century. Many were prominent in trade and moneylending, while some worked as silversmiths, tanners, and tailors. The poorer Jews were peddlers and mostly lived outside the city walls and were vulnerable to attacks.

In 1648-49, the city was under siege for a month during the Chmielnicki Massacres. Jews fought alongside their neighbors to defend Lvov. After the Polish mayor refused to hand over the Jews to the Cossacks, a heavy tribute was paid to lift the siege. The local Catholic Church brought blood libels against the Jews. A number of invasions put economic pressure on Lvov. Even though King John III Sobieski was sympathetic to the Jews, after his death in 1696, the government threatened Jews with trade regulations.

The Hapsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire conquered the area in 1772 and renamed the area Galicia. The rights of Jews were reduced. Shortly thereafter, only wealthy and educated Jews who espoused the German way of life were permitted to live outside the city’s Jewish quarter. By 1800, the two Jewish communities ended up living in the main Jewish quarter outside the city walls. Around this time, most Jews worked as shopkeepers or craftsmen. By 1826, the Jewish population was over 19,000, though many died due to unhygienic living conditions and a typhoid epidemic.

Jews were excluded from some trade. For instance, they could not trade in Danzig and Leipzig and could not participate in the grain trade or leaseholdings. However, they were allowed to partake in trade between Russia and Austria, thus contributing to Lvov’s industrial development. By 1820, Jews owned 265 of Lvov’s 290 stores. For the first time, Jews were accepted into Lvov University in 1806. Graduates and sons of wealthy merchants were part of the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment movement. Herz Homberg, a prominent figure in the movement, founded many schools. Other members of the movement included Yehudah Leib Mieses, Binyamin Tsevi Notkis, Yitsḥak Erter, and Shelomoh Yehudah Rapoport. Jews could enter the professional class. A Jewish hospital, orphanage, elementary school, and temple were built. Various sects of Judaism thrived in Lvov. Lvov became the center of the Hasidic movement by the end of the 18th Century, and a Reform synagogue was built in 1844.

During the 1880’s, the first Zionist organizations in Lvov emerged, publishing pamphlets and starting youth groups. Jews flourished at this time as leaders in business and as doctors and lawyers, though most Jews worked as artisans, shopkeepers, and peddlers. One of the best hospitals in Poland, a Jewish hospital, was founded. Jewish culture also thrived with the founding of a Jewish theatre and the spread of Hebrew and Yiddish literature. Artists such as Yosef Hayyim Brenner and Gershon Shofman were part of the cultural flourishing.

The Jewish population of Lvov reached over 57,000 by 1910. Thousands of refugees fled from the Cossacks to Lvov when World War I began. On September 3, 1914, the Russians took Lvov after the Austrians left. This was the first time since 1772 that Lvov was not under Austrian control. Some 16,000 Jews escaped. The Russians left the city in May 1915, and the Austrian empire ended at the conclusion of the war.

In the wake of World War I, the Poles and Ukrainians fought over Galicia, though Poland remained officially in control of Lvov between the world wars. The government had anti-Semitic policies. There were pogroms in 1917 and 1918, wherein over a hundred Jews were murdered and hundreds more were wounded.

Despite the adversities, Jewish cultural and educational life prospered during this time. There were myriad Jewish schools. Among them were three Jewish high schools with Hebrew language instruction and newspapers. Plus, Lvov had about fifty synagogues. In 1939, the Jewish population reached 110,000, one-third of Lvov’s total population and nearly double what is was only thirty years earlier. Thus, Lvov had the third largest Jewish community in the country.

While cultural life was thriving, professional life declined. Jewish shops closed due to an economic crisis. Jews were denied business licenses, and lawyers were prohibited from practicing. By the 1930s, anti-Semitism went beyond exclusion to outright violence. Thus the stage was set for the Second World War and the Holocaust.

Sources:http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/Lvov.html

https://jewish-guide.pl/sites/lwow

http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Lviv

http://www.history.ucsb.edu/projects/holocaust/Resources/history_of_lviv.htm

Jewish Life in Lvov

Permission to show "Jewish Life in Lvov"" granted by The Spielberg Jewish Film Archive.

Personal Perspectives on World War I

The fighting around Zurawno was very intense during World War I, and left its impact years later, as evidenced by the following story.

The Austrian Cooking Helmet

During the summer of 1943, after living outdoors or in temporary hideouts for several months, Yosef and Kalman Laufer's clay cooking pot broke and they were forced to improvise. "We took with us an Austrian tin helmet of World War I, which we had found in the forest. We spent a few days removing the layers of rust from it and it then became a cooking pot-as long as we had something to put in it. We also used it as a heating device. We kept it with us until the end of the war. In those summer days of plenty, it could hold some twenty potatoes, which were a real feast for us. We always waited hungrily for the darkness to fall and then, when my father had carefully checked the wind direction and the meaning of the rustling and noises around us-only then did we allow ourselves to light the fire and prepare our meal." (From The Fields of Ukraine, (Dallci Press 2009); permission granted by Dallci Press, 4/2/10.)