New Materials Collected After Publication of the Original Book

Appendix Was Not Part of the Original Yizkor Book Yurburg - Professor Dov Levin and Yosef Rosin

Holocaust in Jurbarkas - B. A. Thesis of Ruta Puisyte

"My Life, My Environment, My Epoch - Ze'ev Bernstein"

In the Kovno Ghetto - The Story of Gita Abramson Bereznitzky

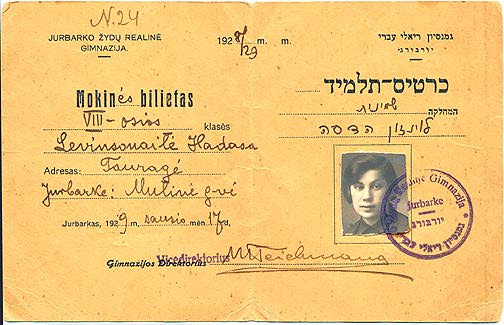

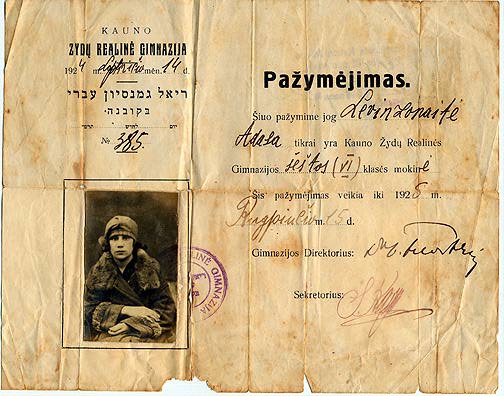

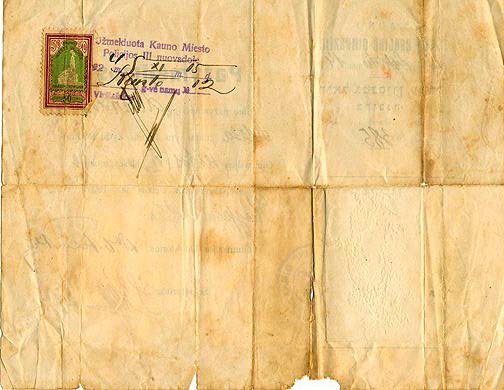

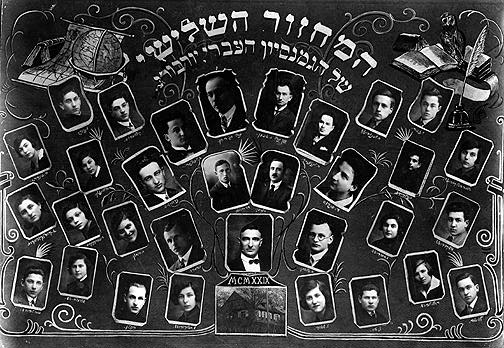

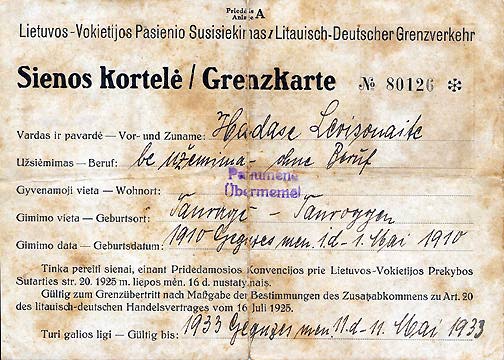

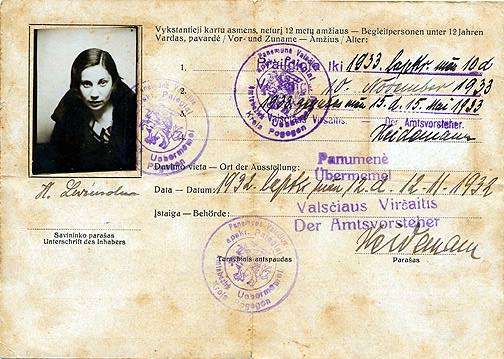

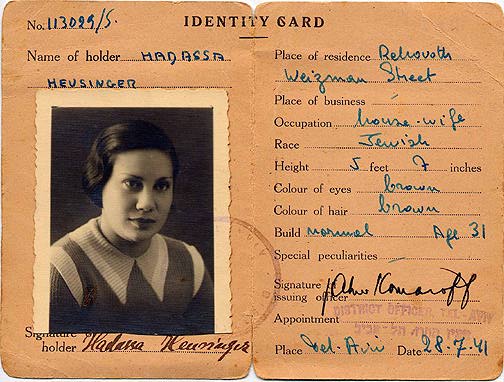

Documents of Her Life - Hadassah Levinsohn Heussinger

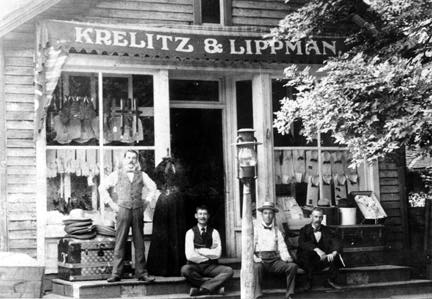

Naividel -Krelitz - Eliashevitz Families

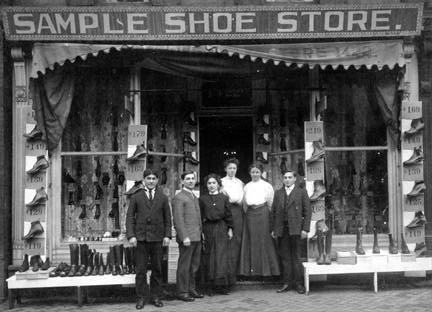

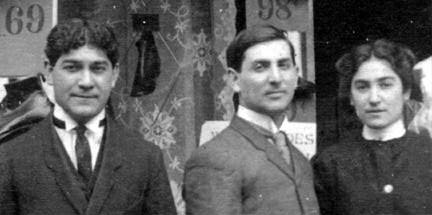

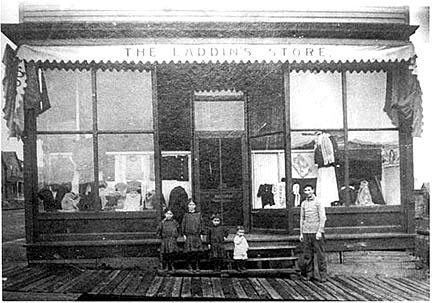

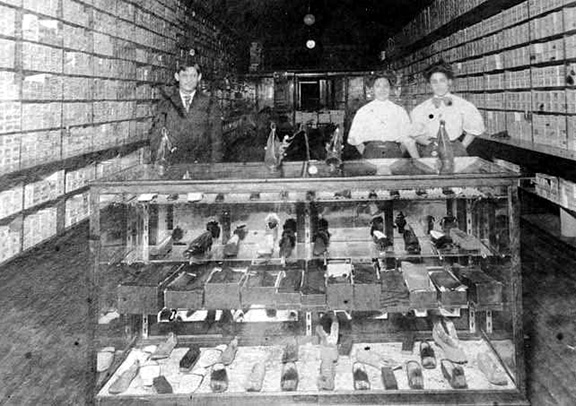

Home on the Iron Range - S. Aaron Laden

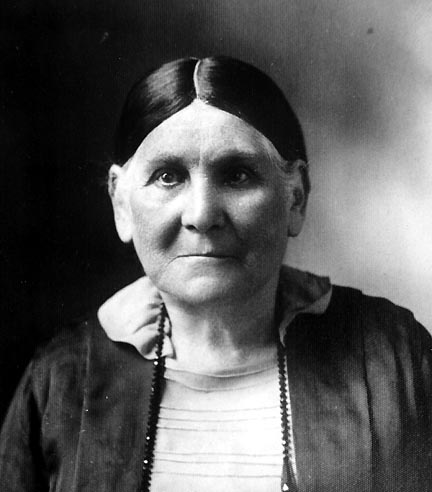

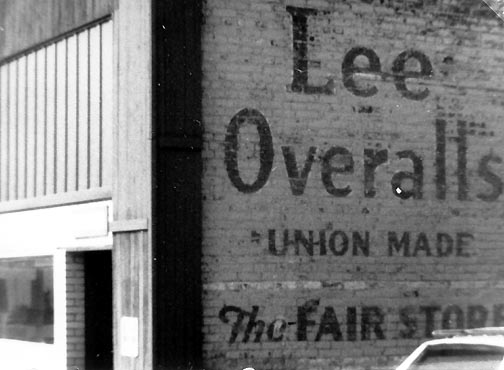

Fanny Ellis Bernstein Rubinstein - End of an Era

Sarah Eliashevitz Laden - Bernard Laden

Max Zarnitsky - Chief Land Appraiser in Israel

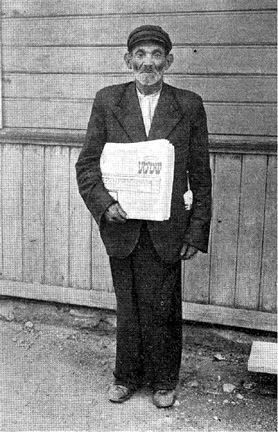

Ben Heshel Craine, Photographer of 1927 Yurburg film

Mordehai (Moti, Motel) Naividel

The Mexican Connection - Max Sherman-Krelitz

Letters from Yurburg 1939-1941 - Krelitz Family

Sudarg by Fania Hilelson Jivotovsky

A Journey to My Past - Fania Hilelson Jivotovsky

Photos from the 2000 Yurburg Family Reunion in Detroit, Michigan

The Yurburg Jewish Cemetery and List of Headstones

We hereby take advantage of the opportunity to add new material that has come to light since the publishing of the original Hebrew book in 1991 and hence it is included here. Since the tone of this material is different from the material in the original Yizkor Book, the editor hopes that the reader understands the intent of including this material is to enrich the content of the book, enhance the history of the town and its descendents and make it more appealing to a wider readership, who can read the history of our community of Yurburg.

This chapter contains new material from the autobiography of Professor Ze'ev Bernstein about his father, Boris, a newly written history of Yurburg written by Professor Dov Levin and Josef Rosin, editor and assistant editor respectively of the Hebrew volume Pinkas Kehilat Lita, Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities of Lithuania, descriptions of the lives of Yurburgers who settled in Israel, Canada and the United States, and a description of a trip to Yurburg and Sudarg taken by descendants of Yurburgers in 2001.

Yurburg

Note: This article was written by Professor Dov Levin and Josef Rosin, Editor and Assistant Editor, respectively, of Pinkas HaKehilat Lita, Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities of Lithuania (Yad VaShem, 1996). This article is based upon and expanded from their article on Yurburg in that book. This article was written especially for this book and was requested by Joel Alpert, compiler of this book.

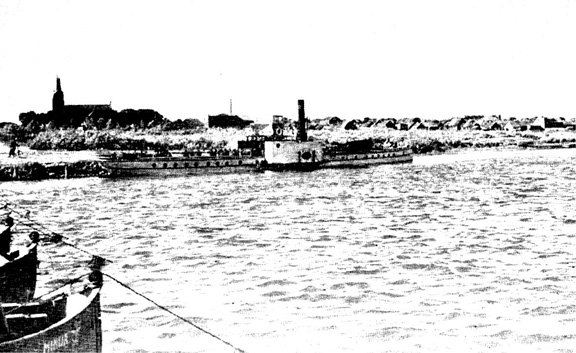

Yurburg is situated on the right hand shore of the Nieman (Nemunas) river where the tributaries Mituva and Imstra converge. The town used to be about 12 km (7.5 miles) to the east of the Prussian border, surrounded by woods. It began as a stronghold of the Knights Order of the Cross in the thirteenth century named Georgenburg or Jurgenburg, but after the border between Lithuania and Germany was defined in 1422, Yurburg became a border town and a customs point. During the thirteenth century the importance of Yurburg increased due to the harvesting of trees in the surrounding woods for commercial purposes, when the logs were floated on the Nieman River to Prussia. Thanks to the ethnic diversity of its inhabitants, its location on a main sailing route - the Nieman - and its proximity to Prussia, Yurburg became a communication and commercial center between east and west. During Russian rule (1795-1915) the town was included in the Kovno Gubernia (province).

As a result of railway construction and road improvement in the region during the nineteenth century, sailing on the Nieman subsided and the growth of Yurburg slowed down. The town was taken over by rebels for a short time during the Polish mutiny in 1831, but after the mutiny was repressed by the Tzar, Yurburg returned to its former life.

German culture from across the border influenced the social life greatly and affected the mode of living in town, which also continued to be the case during the period of Lithuania's independence (1918-1940).

Because of its topographic situation and location between the two rivers and the Nieman, the town frequently suffered from floods. In 1862 eighty houses were inundated and their residents rescued themselves by climbing onto the roofs. Yurburg also suffered from fires, the greatest fires being in 1906 when 120 of its houses burnt down.

Yurburg was first mentioned in the book of Rabbi Meir ben Gedalyah (1558-1616) from Lublin "Sheloth uTeshuvoth" (Questions and Answers) concerning the case of an "Agunah" (deserted wife) whose husband had been killed in Yurburg. The testimonies of this case were reported in 1593 and 1597. During the period of the autonomous organization of Jewish communities in Lithuania "Va'ad Medinath Lita" (1623-1764), Yurburg was included in the Keidan district, and by 1650 there were already seven Jewish houses in town.

In the middle of the 17th century, some Yurburg's Jews earned their living by renting the right to collect taxes for the government in Yurburg, Birzh and other towns, and this was done under the cover of Christians.

At the beginning of the 18th century the community wanted to replace the officiating Rabbi, but he complained to the authorities and received a " letter of protection " from the king. On the 17th of November 1714 Rabbi Aizik. Leizerovitz was mentioned in an official document, but detailed information of Jewish settlement of Yurburg exists only from 1766. At this time there were 2,333 Jews in the town who owned a few prayer houses, among them the magnificent wooden Synagogue built in 1790, one of the oldest in Lithuania. There was also a Jewish cemetery, as well as welfare and religious education institutions. In 1862 there were 2,550 Jews in Yurburg.

Yurburg Jews suffered during the Polish mutiny in 1831. A local resident, Reuven Rozenfeld, was hanged by rebels, who blamed him for aiding the Russian rulers. After the mutiny was quelled, a trial of those involved in the hanging took place for many months, among the accused was a Jew named Tuviyah ben Meir Danilevitz. After being imprisoned in Rasein for 13 months, he was acquitted due to lack of evidence.

In 1843 the Czar issued an order stipulating that Jews living in an area within 50 km of the western border of Russia should be transferred to some of the Gubernias (provinces) inside Russia. Yurburg's community was one of 19 communities that refused to obey this order.

Most of Yurburg Jews made their living from the timber trade, floating timber to Germany, commerce, customs commission, transport and shopkeeping. In 1865 a branch of one of the greatest commercial firms in Germany "Hausman et Lunz" opened in town.

The local garrison was also situated there, providing a living for Jewish merchants. In 1861 Jewish soldiers of the garrison donated money for writing a new "Torah Scroll," which was later brought into the synagogue by the Jewish soldiers, with due festivity. The celebration was attended by respected local people, headed by the commander of the garrison.

At the end of the 1880s a cooperative credit company was established, for which it took three years to receive permission from the authorities.

As a result of the general atmosphere in Yurburg, the "Haskalah" (Enlightenment) movement flourished there among the Jews more than in Zhamut's (Zemaityja region) other communities. This was demonstrated by the cooperation of the community heads in the establishment of a quite modern Talmud-Torah in 1884, where 100 poor children studied, and in addition to religious subjects, Hebrew and grammar, mathematics and Russian were also taught. Members of the management of this institution were: L.Valk, M.H. Kostin and L.Boger, one of the teachers being the famous Hebrew writer Avraham Mapu. Although the school was under the supervision of the government, its financial maintenance was mainly the responsibility of the community. Due to the fact that the 900 Rubles received from the "Meat tax" was not sufficient, the community heads appealed to former Yurburgers in New York, Saint Louis and Rochester in the United States for help. A partial list of donors (who donated from $0.50 to $750) was published in the Hebrew newspaper "HaMeilitz" in July 1889.

The Yurburg Jewish institutions also served smaller Jewish communities in the vicinity, such as Shaudine, Pakelnishok, Gaure. (After World War there were no more Jews in Pakelnishok).

In the Hebrew newspaper "HaMagid" from 1872 there is a list of 39 Utyan donors of assistance for starving Persian Jews. (See Jewishgen-Database-HaMagid-by Jeffrey Maynard).

During the years of famine (1869-1872) which affected many parts of Lithuania, Yurburg suffered less and its Jewish residents donated money to needy communities. The fundraisers were Yitshak-Aizik Volberg and Shelomoh Bresloi.

In a list of donors for the Settlement of Eretz-Yisrael dated 1896, names of 20 Yurburg Jews appear (see Appendix 3). The fundraisers were Tsevi Fain and Avraham-Yitshak Kopelov.

In the old Jewish cemetery in Jerusalem there is a headstone of Rivkah Gitel bat Mordehai Margalioth from Yurburg. During World War I many of Yurburg's Jews left the town, some returning later.

After the establishment of independent Lithuania, Yurburg was included in the Raseiniai district. The number of Jewish residents in Yurburg was smaller than before as some of those who had left did not return and also due to immigration abroad. However, their proportion amongst the whole population increased, as can be seen from the first census performed by the government in 1923. There were 4,409 residents including 1,887 Jews (43%), while in 1897 there were 7,391 residents, of them 2,350 Jews (32%).

In 1922 the elections for the first Lithuanian Seimas (Parliament) took place, with 774 Utyan Jews participating. 477 voted for the Zionist list, 199 for the Democrats and 98 for the religious list "Akhduth."

According to the autonomy law for minorities issued by the new Lithuanian government, the minister for Jewish affairs, Dr. Max Soloveitshik, ordered elections to be held in the summer of 1919 for community committees in all towns of the state. In Yurburg a committee was only elected five years later, in 1924, after much pressure from the National institutions of Lithuanian Jewry (Va'ad HaAretz). The committee (Va'ad) comprised five members of the Workers list, three Zionist-Merchants, two Religious, two Democrats, one "Tseirei-Zion", one Mizrahi and a representative of the butchers. The committee, which collected taxes as required by law and was in charge of all aspects of community life, was active till the end of 1925 when the autonomy was annulled.

Among the 14 members at the local council (later the municipality) elected in 1924, six were Jews, one of them serving as deputy chairman and another as a member of the management. The elections of 1931 resulted in three Lithuanians, one German andone Russian being elected, as well as five Jews: Z. Levitan, M. Shimonov, Y. Grinberg, Sh. Zundelevitz, Adv. H. Naividel, one of them as deputy chairman. In the elections of 1934, when two Jewish lists were presented, four Jews, four Lithuanians and one German were elected.

During this period, as previously, Yurburg's Jews made their living from trade with timber, fish, poultry, fruits and eggs that were exported to Germany. Others dealt in crafts, fishing and shipping, a large part of economic activity taking place on weekly market days (Monday and Thursday) and during the 24 annual fairs.

According to the government survey of 1931 there were 75 businesses in Yurburg, 69 being owned by Jews (92%).

The list of traders according to the type of business is given in the table below:

|

Total |

Owned by Jews |

|

3 |

3 |

|

4 |

4 |

|

13 |

9 |

|

4 |

2 |

|

9 |

9 |

|

2 |

2 |

|

13 |

13 |

|

4 |

4 |

|

6 |

6 |

|

3 |

3 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

5 |

5 |

|

3 |

3 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

4 |

4 |

According to the same survey there were 19 light industries in Yurburg, including 18 owned by Jews (95%), as can be seen in the following table:

|

Total |

Jewish Owned |

|

1 |

1 |

|

2 |

2 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

8 |

7 |

|

3 |

3 |

|

4 |

4 |

In 1937 there were 93 Jewish artisans: 19 tailors, 12 butchers, 12 bakers, 8 shoemakers, 6 barbers, 5 stitchers, 4 painters, 3 hatters, 3 glaziers, 2 oven builders, 2 locksmiths 2 electricians, 2 watchmakers, 2 jewelers, 2 photographers, 1 tinsmith and 8 others. In 1925 there was also one Jewish doctor and 2 dentists.

The Jewish popular bank (Folksbank), established in 1922, which later had up to 400 members, played an important role in the economic life of Yurburg's Jews. Among the great businesses in town the private bank of the Bernshtein family, the "Export-Handel" company and the shipping companies in the Nieman River, should be mentioned.

By 1939 there were 116 phone owners, 41 of them belonging to Jews.

Throughout the ages mutual tolerance existed between the different ethnic groups in Yurburg, and this also continued during Lithuanian rule. However, there were exceptions from time to time, as in 1919, when Yurburg Jews complained to the minister for Jewish affairs in Kovno about a decision by the local authorities that all signs should be in the Lithuanian language only. Previously there had been some signs on Jewish shops in Yiddish or in Hebrew. One of the factors that fostered strong mutual relations was the local branch of the Organization of Jewish Combatants for the Independence of Lithuania, but during the thirties a significant decline took place in the relations between local Lithuanians, Germans and their Jewish neighbors. It expressed itself by the suppression of Jewish commerce, such as the closing of the "Export-Handel" company, in assaults and in the burning of Jewish property, i.e. the flourmill of the Fainberg family.

To the deterioration of the economic situation of Yurburg's Jews, the lower and middle classes in particular, added the many fires and floods caused by the rising water level in the Nieman during the melting of the ice.

Yurburg was famous in Lithuania for its nationalistic atmosphere and Hebrew culture that dominated it. One of the two public parks was almost officially called "Tel-Aviv," and the Hebrew high school was called "Herzl" after the founder of the Zionist organization. In addition to the old Talmud Torah, which was turned into a modern elementary school, a new Hebrew school of the "Tarbuth" chain was also established. There was a public Yiddish library called after "Mendele Mokher Sefarim" and a Hebrew library called after Y. H. Brener.

The "Maccabi" sports organization with about 100 members, an urban Kibbutz of HeHalutz named "Patish" and branches of all Zionist parties, were established. There was also much activity by Zionist youth organizations, such as "HaShomer-HaTsair," "Beitar " and "Benei-Akiva"

The Leftist-Yiddishist movement, the "Jewish Knowledge Society" and the sports organization the "Jewish Workers Club" were also active among Yurburg's Jews. Communist youth too had their supporters.

The table below shows how Yurburg Zionists voted for the different parties at five Zionist Congresses: (See the key below the table)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 -- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 -- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GZ = General Zionists Gm =Grosmanists Rn = Revisionists Mz= Mizrachi

During Nazi rule a member of the illegal Communist youth organization named Yekutiel Elyashuv, who had managed to escape to Russia at the beginning of the war, was parachuted in Lithuania. He fell in battle.

World War II broke out on the first of September 1939, when the German army attacked Poland. A German-Soviet agreement of August 23rd 1939 had stipulated that Lithuania would be under German influence, but that same year, in September 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union decided that Lithuania would be under Soviet influence. Accordingly the agreement of October 10th 1939 stipulated that the Soviet Union return Vilna to Lithuania, this ending its occupation by Poland. This included an area of 9000 square kilometers around the town, and Soviet troops were allowed to establish bases all over Lithuania.

On June 15, 1940, Lithuania was forced to establish a regime friendly towards the Soviet Union, and after the new government headed by Justas Paleckis was installed, the Red Army took over Lithuania. President Smetona fled, Lithuanian leaders were exiled to Siberia, and political parties were dissolved. A popular Seimas was elected, 99% of its members being communists, and decided unanimously that Lithuania join the Soviet Union.

Following new rules, the majority of factories and shops belonging to Jews of Yurburg were nationalized and commissars were appointed to manage them. Most of the artisans were organized into cooperatives (Artels). Some flats and buildings were confiscated. Some enterprises were turned into government institutions, others into public and communal companies.

After these events the supply of goods decreased and, as a result, prices soared. The middle class, mostly Jewish, bore most of the brunt, and the standard of living dropped gradually.

All Zionist parties and youth organizations were disbanded, the Hebrew "Tarbuth" school was closed, and the Yiddish school which was broadened, became an official Soviet institution. At this time Yurburg numbered about 600 Jewish families.

On the 22nd of June 1941 the war between Germany and the USSR began, the German army entering Yurburg on the same day. Many people connected to the Soviet regime tried to escape, but only a small number managed to board a steamer, which sailed to Kovno. Very few managed to escape to the USSR. (See also the BA Thesis of Ruta Puisyte from the University of Vilnius "Holocaust in Jurbarkas " in the next article on page 570.)

Those Jews who remained in town hid in the bathhouse, but German soldiers discovered them and forced them to return to their homes. Although the Gestapo should have processed Jews from Tilzit, during the first weeks of the occupation the fate of the Jews was in the hands of the local Lithuanian police and its newly appointed head, a teacher in the local high school. The Lithuanians forced Jewish youths to work in various jobs, including cleaning the streets. The Lithuanians also forced Jews to destroy the old and magnificent wooden synagogue (built in 1790) with their own hands, including the "Bimah" and "Eliyahu's Chair" with their splendid ornamental wooden carvings.

During this work, Jews were beaten and mistreated, one example being when a brick was fixed to the town cantor's beard (Alperovitz) and he was thus led through the streets. On Saturday, June 28, 1941, Lithuanian police forced the old Rabbi Hayim-Reuven Rubinshtein as well as Jewish family heads to bring all Torah scrolls and other holy books to the synagogue yard to burn them. The next day policemen made Jews run through the streets in a so-called procession, while a sculpture of Stalin was carried ahead. In front of a curious crowd, Jews were forced to dance and humiliate themselves by declaiming speeches that were dictated to them and similar actions. Several Jewish doctors and learned people were murdered, after having been humiliated and tortured by local Lithuanians.

On the 3rd of July 1941 (7th of Tamuz 5701) German and Lithuanian police detained 322 Jews, whom they led to the Jewish cemetery cruelly beating them on the way, and then shot them one by one near the pits which had previously been dug. One of the victims was the exporter Emil Max, who as a German soldier during World War I, was decorated with an Iron Cross, first degree. He attacked a Gestapo officer, and was shot dead immediately. After the carnage a party for the murderers was arranged in town.

On the 27th of July, 45 elderly Jews were put on carts to be taken to Rasein for a supposedly medical inspection. After a journey of 15 km they were murdered together with the coachmen who transported them and with Jews from neighboring villages. On the first of August, 105 elderly Jewish women were murdered in the same manner. On the 4th of September, 520 women, children and relatives of the 322 men, victims of the carnage of the 3rd of July, were imprisoned for 3 days in the yard of the Jewish school, after which they were transferred to the yard of Motl Levyush which served as a labor camp. At midnight, the 7th of September, these women and their children, who resisted and hit the Lithuanian murderers with their fists and shouted with anger, were led to the Smalininkai grove (seven kilometers from Yurburg), where they were shot with rifles and machine guns, with only a few girls managing to escape. One week later the last 50 Jews, who had been left temporarily in Yurburg for work, were murdered too. Only a few were hidden by peasants.

During the three years of Nazi occupation, several Jews who managed to sneak away from the hands of the rulers and also from local residents who were liable to betray them to the police, roamed around in the surroundings of Yurburg and Staki. The Fainshtein brothers, armed with automatic weapons, met a Soviet pilot whose plane had been shot down, and together they acted as a partisan group.

Later on several tens of Jews from the Kovno ghetto and from other places joined this group and in the spring of 1944 they numbered 35-40 armed fighters. From time to time they attacked German vehicles on the roads and punished Lithuanian collaborators. When the frontline approached their base, they were suddenly surrounded by German gendarmerie and after a short fight all fell in battle. From this group only two wounded women and five men (among them the Fainshtein brothers who were absent from the base during the fight) survived. Among Yurburg's Jews those who survived were those who had managed to escape to Russia, those who arrived in the Kovno ghetto and several others who fought with the partisans.

After the war a monument was erected on the mass graves.

In 1991 "The Book of Remembrance" of Yurburg Jewish Community" was published in Hebrew and Yiddish, edited by Zevulun Poran (Petrikansky).

The number of Jewish survivors who returned to live in Yurburg decreased, in 1970 there were nine Jews, in 1977 there were four, in 1998 only five, and in 2001 there were none!

In 1991-92 the government cleaned and restored the old Jewish cemetery.

Yad Vashem Archives: M-/Q-1314/133; M-9/15(6); TR-10/40,275 Koniukhovsky Collection 0-71, files 49,50.

Central Zionist Archives-Jerusalem, Z-4/2548; 13/15/131; 55/1788; 55/1701; JIVO, Collection of Lithuanian Communities, New-York, Files 507-509, 1388, 1523.

The Oral History Division of the Institute of Contemporary Jewry, the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, evidence 65/12 of J.Tarshish.

Gotlib, Ohalei Shem, -page 93 (Hebrew).

Kamzon J.D., Yahaduth Lita (Lithuanian Jewry), pages 147-154 (Hebrew), Rabbi Kook Publishing House, Jerusalem 1959.

Levin Sh.- "Lithuanian Jews in the 1831 Uprising"- YIVO Pages.

Poran Zevulun-Sefer haZikaron leKehilath Yurburg-Lita, (Hebrew and Yiddish) Jerusalem 1991.

Dos Vort -daily newspaper in Yiddish of the Z"S party, Kovno-30.10.1934; 11.11.1934; 12.2.1939.

Di Yiddishe Shtime-daily newspaper in Yiddish of the General Zionists-Kovno, 24.8.1919; 3.9.1919; 4.4.1922; 25.4.1923; 19.10.1924; 23.11.1924; 19.6.1931; 28.8.1931; 5.10.1937.

HaMeilitz, St.Petersburg, (Hebrew), 18.8.1886; 3.1.1889; 19.4.1889; 19.2.1899; 2.7.1893; 6.3.1901.

Folksblat - daily newspaper of the Folkists, Kovno (Yiddish), 7.3.1933; 10.4.1935; 16.7.1935; 21.3.1937; 29.3.1937; 5.10.1937; 20.11.1940.

Funken, Kovno (Yiddish), 8.5.1931.

Di Zeit (Time), Shavl (Yiddish)-5.6.1924; 6.5.1924.

Hamashkif - daily newspaper of the Revisionist party, Tel-Aviv (Hebrew) 22.4.1945.

Forverts -New York (Yiddish)-4.4.1946.

The Small Lithuanian Encyclopedia, Vilnius 1966-1971 (Lithuanian).

The Lithuanians Encyclopedia, Boston 1953-1965 (Lithuanian).

Lite, New-York 1951, volume 1 & 2 (Yiddish).

Yahaduth Lita, (Hebrew) Tel-Aviv, volumes 1-4.

Masines Zudynes Lietuvoje 1941-1944 (Mass Murder in Lithuania 1941-1944) vol. 1-2, Vilnius (Lithuanian).

Pinkas haKehilot Lita (Encyclopedia of the Jewish Settlements in Lithuania) (Hebrew). Yad Vashem. Jerusalem 1996, Editor Dov Levin, Assistant editor Yosef Rosin.

The Book of Sorrow, Vilnius 1997 (Yiddish, Hebrew, Lithuanian, English).

Cohen Berl,. Shtet, Shtetlach un Dorfishe Yishuvim in Lite biz 1918 (Towns, small Towns and Rural Settlements in Lithuania till 1918) (Yiddish) New-York 1992.

Gimtasis Krastas - (Country of birth) (Lithuanian) 8.9.1988.

Naujienos ,Chicago-(News) (Lithuanian) 8.9.1949.

Sviesa, Jurbarkas, (Light) (Lithuanian) 12.7.1990; 8.8.1990; 11.8.1990.

Valstieciu Laikrastis-(Farmers Newspaper) (Lithuanian) 26.4.1990.

Aizik Leizerovitz - mentioned in an official document in 1714.

Aryeh-Yehudah-Leib - during the18th century.

Yehushua-Zelig Ashkenazi (about 1785-1831), refused to accept a salary because he had a rich father-in-law.

Mosheh haLevi Levinson, from1861 in Yurburg.

Ya'akov-Yosef ben Dov-Ber (1841-1902), from 1888 a Rabbi in New York where he died.

Yehezkel Livshitz (1862-1932), in Yurburg 1887-1891.

Avraham Dimant (1863-1940), in Yurburg for several tens of years until his death.

Hayim-Reuven Rubinshtein (1888-1941), the last Rabbi of Yurburg, murdered by the Lithuanians.

Most of the above mentioned Rabbis published books on religious matter.

Shelomoh Fainberg (1821-1893), philantropist, moved to Kovno in 1857, married Baroness Rosa von Lichtenstein from Vienna, in Koenigsberg from 1866. He received the title of " Councellor of Commerce " from the Czar, and died in Koenigsberg.

Shelomoh Shakhnovitz - author of the book "The Skill of Reading the Torah" (Keidan 1924).

Mendel Shlosberg (1843-??), moved to Lodz, where he participated in the development of the Polish textile industry.

Shelomoh Goldstein (1914-1995), a graduate of the Hebrew high school in Yurburg and a graduate of Rome university in chemical engineering, one of the leaders of "HeHalutz" in Lithuania, was imprisoned in the Kovno ghetto. Lived in Skokie, USA, from 1948, a philanthropist who supported many Jewish and Zionist institutions in America and in Israel, among them the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. For many years a member of the Zionist executive.

Zalman and Tuviyah Samet, born in Yurburg in 1857 and 1858, founders and directors of the big firm "Brothers Samet" in Lodz.

William Zorach (1887-1966), sculptor and painter, also painted many pictures on Yurburg. He died in Bath, Maine, U.S.A

Shelomoh ben Yisrael Bresloi, a learned man and philanthropist, donated 500 Rubels for establishing a "Gemiluth Hesed" in town.

Hirsh Noteles, sent a Hebrew poem to the Czar and received a letter of thanks and a golden ring as a memorial gift.

- Gut Leib Segal Ya'akov

- Garzon Mordehai Fainberg Gavriel

- Homler Avraham-Leib Pustapedsky A.H.

- Helberg Shemuel Kopelov Avraham-Yitshak

- Hershelevitz Avraham Kaplitz Hertz

- Yablonsky David-Shelomoh Rubinovitz Max

- Yozefer Hayim-Nathan Dr.Tsezar Rabinovitz

- Yozelit Hayim Rochelson Shimon

- Leibovitz Aba Rivkin Dov

- Mendelson Leib

- Myakinin Avraham

- The fundraisers were Tsevi Fain and Avraham-Yitshak Kopelov.

Contents Introduction

1. The economic, social and cultural life of the Jews of Jurbarkas in Lithuania (1918 - June 1941) 2. The mass extermination of the Jews in Jurbarkas. (June 1941 - September 1941)

2.1 Events in June 1941

2.2 Events in July 1941

2.3 Events in August 1941

2.4 Events in September 1941

2.5 The Jewish Ghetto in Jurbarkas

3. The fate of the Jewish survivors of Jurbarkas in Lithuania after the June - September 1941 Events

Conclusions

Bibliography

Appendices

Footnotes

In 1941-1943 the Lithuanian Jewish Community, which had existed in Lithuania for centuries, was struck by a catastrophe never experienced before in world history: the community was cruelly massacred by the Nazis and their local collaborators. Only the graves, a handful of the living and a never-fading memory remained. Though more than half a century has passed since this horrible catastrophe, historians in Lithuania still have not conducted research into how and when such a regional community was destroyed. From this prospective, Ruta Puisyte's bachelor's thesis on the massacres of the community of Jurbarkas is the first attempt to fill this void. The author was not driven merely by scientific interest. She is a young and talented Lithuanian historian, whose conscience demanded that she reveal one of the bitterest truths in Lithuania's mid-century history.

One outstanding feature of this thesis is that the author details not only the dates and the places of massacres, but she also names the victims, their executioners, and those righteous Lithuanians who saved Jews.

I hope that the English translation of the paper will be useful to those people all around the world who carry out investigations of the Holocaust.

Professor Mejeris Subas, Head of the Center for Judaic Studies The University of Vilnius

As a person who has learned from his own personal experience about the massacre of the Lithuanian Jewry, fortunate to arrive to Eretz-Israel in 1945, and actually take part in the establishment of the State of Israel and for tens of years has been engaged in researching Lithuanian Jewry and its annihilation, I have a particular interest in presenting to the "Litvaks" (Lithuanian Jews and their descendants) and the general public the important work of Miss Ruta Puisyte. Her thesis was completed to fulfull the requirements of her Baccalurate degree under the guidance of my longtime colleague Professor Mejeris Subas (Meyer Shub), Head of The Center of Judaic Studies of the Vilnius University. Miss Puisyte systematically reviewed the history of the Jewish Community of Jurbarkas (Jurburg, Lithuania) and in particular its terrible fate during the Holocaust. She also precisely documented the names of the murderers. Her findings not only reveal her patience and the arduous work needed to collect data from a variety of sources, but the work also displays her objectivity in documenting the horrific details describing the cruelty and murders perpetrated on the Jews. In the social reality of present-day Lithuania she also exhibited a great deal of personal courage, integrity and bravery to reveal, by name, those who were the murderers. Therefore this work has a greater significance than it's scientific merit because it can serve as a model to others to also seek and report the truth intelligently and with integrity. As a consequence of this thesis it is clear that it would not be an exageration to say that such work merits respect and dignity to the Vilnius University which is striving to earn its place among the other research institutions in the western world.

It is my honour and pleasure to thank my good friend Joseph Rosin who volunteered to translate this book from Lithuanian into English so as to enable the English-speaking population all over the world access to its contents. Mr. Rosin was also my assistant in editing the Encyclopedia of the Lithuanian Jewish Communities (Pinkas haKehilloth. Lita, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem 1996) which also served as a primary source to Miss Puisyte in preparing her thesis.

Jerusalem, June 1998-Sivan 5658 Professor Dov Levin, Head of the Oral History of the Institute of Contemporary Jewry, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

A few comments on the English translation:

1. All the books and articles mentioned in this thesis were written in Lithuanian except The Encyclopedia of the Jewish Communities in Lithuania (Pinkas haKehiloth Lita) which was written in Hebrew.

2. All the Jewish names mentioned in this thesis were written without the Lithuanian endings in the English translation and spelled as they were pronounced in Yiddish.

3. I thank my friends Sarah and Mordechai Kopfstein for helping to translate this thesis.

Text added by Joel Alpert in further editing for clarification is contained in {brackets}.

During the years of the German Nazi occupation of Lithuania several hundred thousand people were murdered, among them about 170,000 to 180,000 Jews, i.e. about 94% of the Jews living in Lithuania before World War II. After three years of war, out of the 200,000 Jews who had lived there before the war, only 8,000 to 9,000 Jews remained alive in Lithuania.

After Lithuania regained its independence, the subject of the Holocaust (Katastrofa in Lithuanian) was opened up for investigation. The murder of the Jews in Lithuania during the years of World War II was not only a great numerical loss of the country's citizens, but also an historic problem strongly related to justice being done for a crime actually committed and to the punishment of actual persons. It is a pity that this historic tragedy is essentially only being investigated half a century after it happened.

The mass extermination of the Jews in the chronological margin of the 1941-to-1944 period is part of the now popular research in Lithuania being carried out by historians and non-historians with regard to the 1940-to-1956 period. During this period, people experienced Soviet occupation and reoccupation, the uprising of June 23, 1941, resistance after the war, and exile. When conducting research into all the aspects of this period or of particular problems in it, the theme of the Jewish Holocaust became just one part of the whole process.

The search for the accused in the mass murders is a painful question for the Jews as well as for the Lithuanians. Is the nation guilty (moral responsibility)? Is the government guilty? Or maybe only individual people are guilty? Historic research could help to investigate the many aspects of this problem and answer these questions, also for people from the extreme fringes of society, amongst whom "all Lithuanians were Jew killers", and "all Jews were communists."

This work deals with events in Jurbarkas during the period of the three months (June to September 1941), starting from June 22, 1941 till the middle of September 1941. If we divide the extermination of Lithuania's Jews into three periods - a) June 1941 - December 1941; b) January 1942 - June 1943; c) July 1943 - July 1944 -, then the above three months take up less than a half of the first period and in this short time the town of Jurbarkas lost half of its inhabitants. 2,000 Jurbarkas Jews among the 170,000 murdered are but a drop in the ocean when referring to numbers, but we are dealing with human beings and therefore 2,000 people is a very significant number.

In 1941, the town of Jurbarkas was 10 kilometers (6 miles) distant from the Lithuanian SSR-German border. At 8 o'clock on the morning of June 22, 1941, the German Army marched into the town. The town was situated within the 25 kilometers border strip controlled by the Tilzit operative group. The future of the Jews was determined by German politics, but the fate of individual Jews depended on the friendship or hate of individual Lithuanians. During the first months of the war the Nazis did not as yet have an official plan for solving the Jewish Problem. "The Final Solution" was only drawn up in January 1942, during the Wannsee Conference.

One of the particular characteristics of Jurbarkas was that it was a border town, and the other, that it was situated in the Lithuanian provinces. Here the mass murders of the Jews were performed abruptly and quite "silently, with the same cruelty as in the big cities, and the perpetrators did not expect any massive resistance from the victims or other disturbances.

During the years of Soviet rule the Jews' mass extermination by German fascists and local collaborators was not investigated. Many books were published about the crimes of the Hitlerites and the "bourgeois nationalists." There were many documents3,4,5 and books dealing with particular regions of Lithuania and particular locations, such as Panevezys6, Kretinga7, Dzukija8 and others.

Some data about Jurbarkas can be found in the collection of documents "Mass Murders in Lithuania." In the second part of this book, where the crimes of the Tilzit operative group are detailed, mention is made that "on July 3, 1941, 322 persons were shot in Jurbarkas." Furthermore, mentioning the fate of the survivors, (the murderers knew that the number of the victims was greater), it said: "In some indefinite place on some indefinite day an indefinite number of people...."9 This intensifies the motivation and importance, from a Jurbarkas point of view, to search the archives for documents and supplementary collections of memoirs.

In the collection of memoirs of Mrs. S. Binkiene11, there is a story about the fate of Jurbarkas's Jews, by S. Rozental "Macijauskas." During World War II this man hid a few Jews and among them a native of Jurbarkas, David Levin.

Among the recent literature it is worthwhile mentioning a specially published book12 about Jurbarkas in which, in separate articles, particular themes are discussed, i.e. schools, the vocations of its inhabitants, healthcare and more. The information in this book was very important when writing the first part of this thesis - i.e. the economic, social and cultural life of the Jews in Jurbarkas between the two world wars.

This thesis also used a particular article from the Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities in Lithuania13 published in Israel, about the history of Jurbarkas Jews. I am very grateful to the Vilnius resident Mrs. Riva Bogomolnaja for her translation of the Hebrew text into Lithuanian.

This work was supported by documents from two archives: The Central Lithuanian State Archives (LCVA) and the Special Archives (LYA). From the central archives file Number 1753 was used, the documents of the municipality of Jurbarkas, paragraph Number 3, in which there were orders from the Siauliai (Shiauliai) Gebietskomissar, head of the Raseiniai region, from the mayor of Jurbarkas and others. Also statements and correspondence on the execution of orders by the town's occupation power, personal, economic and financial questions. Many files were reviewed, but there were only a few documents relating to the subject of this work.

In the special archives many files were found regarding the murderers of the Jews. But the murder of Jews was of minor importance, because the accused mentioned in these files very often took part in other "punishment deserving" activities - he would be a partisan (against the Soviets), or belonged to some "nationalist" organization and the like, which interested the Soviet courts a lot more. In these courts the questions to the accused were designed in such a way as to take into account that the answers had been arranged beforehand, always weighted against the accused. This does not mean that the files in the aforementioned archives are not a credible historic source. After these archives became accessible to researchers, the possibility opened up investigation into the Holocaust in Lithuania by relying not only on memoirs or the press of those days, or archives material of high German and Lithuanian institutions, but also took into account the evidence given after the war by murderers and witnesses in Soviet hearing and court institutions. A critical approach to these sources helps the historian to remain objective.

The second part of this thesis describing the Holocaust of the Jews in Jurbarkas, tries to record the events of this four-month period chronologically. It was impossible to order all the events chronologically by relying only on documents from government archives, and it was essential to obtain additional historical sources.

The bases of this work are the collected and recorded memoirs of Chayim Jofe. Chayim Jofe (1916-1995), a Jurbarkas Jew, who dedicated the last ten years of his life to collecting material about his murdered fellow-citizens. I am very thankful to his widow, Mrs. Brone Jofe, who willingly allowed me to use her husband's archives. I used them for the part they tell about the Holocaust, for parts 1 and 3 of this work, and the Appendices were taken from copies of Chayim Jofe's archives existing in the Lithuanian State Jewish Museum (LVZM).

Some of the events of June-September 1941, mentioned in short articles, were taken not from Chayim Jofe's personal archives, but from those published in the newspapers.

Speaking about the investigations of some Lithuanian authors into the Holocaust after the re-establishment of independence, it is worth mentioning that there were no wider studies and it was difficult to get a many-faceted view of the subject. Apart from this, almost everything which was written about Lithuanian - Jewish relations, was neither scientific nor journalistic, but rather emotional, with many prejudices and stereotypes being involved.

The goal of this B.A. thesis was to use the scientific research methodology to analyze the Holocaust in Lithuania.

The topics of this work include:

Jurbarkas was not chosen as the object of inquiry on the assumption that there would be source material available. On the contrary, this thesis' theme was chosen before having any knowledge of where to obtain any material. Therefore I am very thankful to the people who helped me collect material and delivered it to me. They were: Mr. Gediminas Grybas14; Mrs. Rachele Kastanjan15; Mr. Iliya Lampert; Mr. Josef Levinson16; Mr. Asher Meirovitz17; Mr. Zalman Kaplan.

Jurbarkas (in Yiddish - Jurburg/Jurburk) is situated in the valley of the river Nemunas (Nieman), on its right bank. It is difficult to state the exact period when the first Jews settled there, but it is known that in 1650 there were seven Jewish houses, i.e. about eight families18 in Jurbarkas. During the follwing years this number increased significantly.

During the years of the Lithuanian Republic, Jurbarkas was the regional center in the Raseiniai district. According to the first population census of Lithuania in 1923, Jurbarkas then had a population of 4,409 people, among them 2,031 (46%) Lithuanians and 1,887 (43.2%) Jews (880 men, 1,007 women)19 .

There now follows a description of the economic, social and cultural life of Jurbarkas's Jews during the period of the Lithuanian Republic, with emphasis on the end of the fourth decade - the eve of the Holocaust.

Due to the geographic situation of Jurbarkas throughout its history the main occupations of the town's citizens were concentrated in commerce. Most of Jurbarkas's merchants, i.e. 70 to 80 %, were Jews20, in other words, about 92% of Jurbarkas's Jews were engaged in commerce21 .

In 1931 there were 73 shops in the town, of which 66 belonged to Jews22.

|

Total |

Owned by Jews |

|

3 |

3 |

|

4 |

4 |

|

13 |

9 |

|

4 |

2 |

|

9 |

9 |

|

2 |

2 |

|

13 |

13 |

|

4 |

4 |

|

6 |

6 |

|

3 |

3 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

5 |

5 |

|

3 |

3 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

4 |

4 |

The Jewish merchants were different: there were small shops (selling so called ‘colonial' merchandise) and they were owners of big shops and warehouses, such as: Yakov Golde who owned a shoe warehouse; Bela Nevjark - cotton knitwear; Max Simonov traded in iron products and agricultural machines; Moshe Krelitz - silver and other metal products; Sarah Israel dealt with office equipment.

It should be mentioned that although it was a small town, at that time commerce was already quite specialized.

According to 1931 data, 19 light industries were actively producing in Jurbarkas, of which Jews owned 18:

|

Total |

Jewish Owned |

|

1 |

1 |

|

2 |

2 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

8 |

7 |

|

3 |

3 |

|

4 |

4 |

Most of these industries were small, employing one to three workers. But they also had shop outlets, i.e. the owner of a meat products factory also had a meat shop, a bakery owner also had a bread shop, etc.

There were also bigger factories or workshops. The brothers Fainberg owned a flourmill, a power station and a sawmill; Itzik Geselowitz had a lemonade factory (he also owned the cinema "Triumf"); Girsh Margolis, O. Sefler, K. Krom - each had a furniture workshop.24

Many of Jurbarkas's Jews were the owners of various means of transportation, such as, in those times were very expensive, buses, trucks, floating barges and steamships on the river Nemunas. For example, Yakov Golde was the owner of four buses and three trucks. In 1940, 14 steamships, 15 motor ships and 39 barges were sailing on Lithuanian rivers, a third of them belonging to Jews from Jurbarkas as follows: Israel Levinberg, L. Aizenshtat, J. Fainberg, Moris Arshtein, J. Lubin, Arel Aremjan and David Karabelnik25

There were two Jewish banks in Jurbarkas, one of which was established in 1922 and called the "Volksbank" with about 400 members, whereas the other was a private bank and belonged to Bernshtein26.

In 1939 Jurbarkas had 116 telephones, 41 belonging to Jews.27

In 1940 there were five hotels and lodging houses in Jurbarkas, of which four belonged to Jews. The hotels were owned by Yitzchak Fridman, Roza Berkover and Shmuel Limas and the lodging house belonged to Chashe Finberg. Chaya Polak, Motl Kaplan and Moshe Kaplan each had a restaurant. Mrs. Kabilkovsky28 was the owner of a teahouse.

The most popular crafts among the many Jewish craftsmen in Jurbarkas were shoemakers, tailors, blacksmiths and stove builders. There were also unskilled and part-time workers, such as porters, coachmen, raftsmen etc. being representatives of the less prestigious professions29 .

There were also workers in the liberal professions, in health and in education. N. G. Naividel was a lawyer.

In 1925 a government lung hospital was established in Jurbarkas, but there were also people engaged in private medicine. In a journal called "Medicine" (1920, Number 5) two practicing doctors are mentioned in Jurbarkas: Elias Levin with fully certified papers because he was a graduate of Dorpat University and passed the examinations in Russia, and Leib Gershtein, who did not pass those examinations.

In this "Medicine" journal (1920, Number 7) there is a list of dentists, mentioning two Jurbarkas citizens, Mordechai Simonov and Moshe Rikler.

Later on the Health Department started to publish, in the "Medicine" journal's supplement, lists of the practicing doctors, veterinarians, pharmacists and health institutions in Lithuania. In its list of 1922 there were three doctors who had temporary permission to practice medicine, being: Leib Gershtein, born 1891, completed medicine in 1923 in Kaunas; Tuviah Goldberg, born 1887, graduated in 1914 in Petrograd; Elias Levin, born 1890, graduated in 1916. Of them only L. Gershtein, who received his rights to practice in Kaunas in 1923, was mentioned in the list of 1928 to 192930.

Sources dating back to 1888 already mention the Jewish pharmacist Markus Bregovsky. His pharmacy continued to exist, managed by his heirs, till 1940, when it was nationalized. In 1923, two pharmacies were in business in Jurbarkas, belonging to Fania Bregovsky and Shmerl Fin. Josl Shabashevitz worked as assistant pharmacist, having concluded his studies in 1914 in Dorpat. Elias Rabinovitz - graduated in 1888 in Moskow - was a qualified pharmacist. Later Goldberg, M. Bregovsky, J. Fin, G. Zundelovitz were added to the list. In the list of 1923, a new doctor appeared, named Josef Karlinsky, born 1880, having received his rights to practice in Kaunas in 1923. In the list of 1936 another two new doctors are shown: Josef-Ber Girshovitz, born 1901, graduated in 1933 and Basia Naividel-Maizler, graduated in 1928 in Kaunas. In 1936 four dentists practiced in Jurbarkas, two of them Jews: Miriam Kopelov-Goldengeim, born 1902, graduated in 1926 in Kaunas and the already mentioned M. Simonov. During the fourth decade the number of pharmacies in Jurbarkas stabilized. There were two, one belonging to Bregovsky (director Miss Libe Katz, born 1906, graduated 1933 in Kaunas), and the other, the so-called " Central Pharmacy" (Owners Sh. Fin and L. Flier). In the list of 1938 we found the assistant pharmacist Elena Flier-Surasky, born 1895, who graduated in 1918 in Petrograd. Doctor Boris Reichman31, not mentioned so far, worked in Jurbarkas's hospital in 1940.

The Jewish children of Jurbarkas were able to study in three schools32

On September 1, 1921 the Jurbarkas Jewish High School was inaugurated, with Hebrew as the language of instruction. The initiator of the project for the establishment of this school and its organizer was J. Fainberg. At the end of 1921 the school had enrolled 104 pupils in four classes and during this year seven teachers worked there: the director A. Efros, Itzik Tzintovsky, D. Verblovsky, Miss E. Rabinovitz. In 1922 a fifth class was established and by the end of that year the school consisted of 140 pupils and nine teachers. According to 1924 data, 140 pupils studied in the school at that time. The tuition fee was then 30 to 60 lit ($1=10 lit) per month, but about 20% of the pupils were exempted from payment of tuition.

Being a private school, it did not receive any financial support from the Ministry of Education. By 1925 this school grew to include seven classes, 139 pupils and nine teachers. In 1926 there were eight classes and 144 pupils. On April 24, 1934, the director of the high school D. Kagansky, not being able to solve the financial problems of the school, announced that as from the first of July the Jewish High School in Jurbarkas would be closed down. In 1934 there were only 46 pupils studying in this high school, whose scholastic achievements were quite low.33

Two of the town's elementary schools were Jewish. One of them was school Number 3, called "Talmud-Torah", in which the teaching language was Hebrew. In 1944 the withdrawing Germans set fire to it. During the years 1924-1939 five teachers worked in this school: the director D. Gershon, Tchechanovsky, Chayim Sigel, Chayim V. Jozefer, Miss M. Joselzon.

Another Jewish elementary school was school Number 5, called the "Volksschule." In this school, situated in the poor Jewish neighborhood, the teaching language was Yiddish and there was no tuition fee. It had been established in 1921 and was kept going with the help of the Jewish Community. Its first director was Miss Dora Fainberg, and during the years 1931 to 1940 the director was Basia Gut. Forty to fifty pupils attended this school in four classes.

Jurbarkas Jews also participated in the town's administration. The town council of 1918 had 23 members, consisting of 16 Lithuanians, three Jews, three Germans and one Russian. On April 30, 1919 the town's social care department was established and on its board there also served a Jew, I.Rabinovitz. In 1931 three Lithuanians, one German, one Russian and five Jews (Levitan, Simonov, Grinberg, Zundelovitz, and Naividel) were elected to the town council. In the elections of 1934, four Jews won election to the town council, and one Jew, Sh. Fainberg, became the alternate mayor35.

Honorable and intelligent people were elected as leaders of the Jewish community36, so that at different times there were such leading figures as Hirsh Fin, Pinchas Shachnovitz, Israel Levinberg, Shmaya Fainberg, Alter Simonov, Meir-Zuse Levitan, Reuven Olshvanger, Josef Karlinsky. The members of the social committee in 1923-1924 consisted of five laborers, five merchants (two of them wholesalers), and two delegates of the intelligentsia and three of the synagogues.

The Rabbis of Jurbarkas: Jakov Josef Charif (emigrated to USA and became a Rabbi in New York); Jechezkel Lifshitz (later Rabbi in Kalish); Avraham Dimand (1863-1940, famous as a Gaon) and the last Rabbi Chayim Reuven Rubinstein (1888-1941, famous as a writer, who published his own book)37.

At the end of the eighteenth century the Jurbarkas's Jews had been able to build a big wooden synagogue, an interesting and valuable architectural structure, its interior being a carved work of art, the most beautiful wooden synagogue in Lithuania. During the nineteenth century and not far away, the Jews also erected a synagogue built of brick. Both were the center of the spiritual and public life of Jurbarkas's Jews.

Jurbarkas Jews had an extensive, varied cultural and public life, and following herewith is a description of some of the Jewish organizations.

The Jewish national- democratic educational association, which directed the athletic club "JAK", a library, a reading room, art circles. "Hapoel" (The Worker) - a leftist sports organization.

The Zionist organizations: Hashomer Hatsair" (Young Watchman) connected to the "Scouts." Their uniform was green blouses and blue neckties. "Hechalutz" (The Pioneer) prepared Jewish youth for agricultural work in Palestine. On the extreme right there was "Betar" (named after Joseph Trumpeldor) with its militant wing "Beit Hahashmal. There was also "Maccabi", the Zionist youth sports organization.

The Jewish volunteers who took part in Lithuania's battle for independence had their own association38.

Quite a few charity associations were active in Jurbarkas: "Hachnasat Orchim" (Shelter for Passersby) and cared for beggars; "Hachnasat Kala" collected money for poor brides' doweries; "Bikur Cholim cared for the sick; "Somech Noflim" aided the impoverished; "Gmilath Chesed" provided loans to poor people on easy terms; "Tzdaka Tatzil Mimaveth" (Charity Saves from Death) collected money for funerals.

A Jewish drama group also existed in Jurbarkas, whose members were: J.Arshtein, I. E. Pelbaum (or Perlbaum), D. Tchertok, M. Fidler, D. B. Portnoy, I. Purvas, Miss B. Jozefer, B. Shmulovitz, G. Kravetzky, H. Sh. Michelson, M. Beder, H. Zarkin, M. Shmulovitz, Katriel Levin and others (mostly youths)39.

The Jewish community of Jurbarkas, having a valuable cultural and a wealthy economic life had to face two foreign occupations of the Lithuanian Republic, one following the other.

On July 21, 1940, Soviet rule was proclaimed in Lithuania. This thesis does not deal with the Jews' reaction to this situation in detail, but it is interesting to note how many communists and commsomols (members of communists youth organization) were among Jurbarkas's Jews. In Chayim Jofe's list of Jurbarkas's Jews who were killed, there were four40: Miss Sheine Geselkovitz, Miss Mika Lubin, Leib Polak (these three were comsomols), Boris Reichman (a communist)41.

During this year of Soviet rule, the organizations were closed down, private and public property was nationalized, and this disaster included both Jews and Lithuanians. The banishment into exile of June 14 and 15, 1941 badly effected several Jurbarkas Jewish families. In the list of those "deported to Soviet Russia"42, drawn up during the years of the German occupation, these Jews can be found:

Chayim Polovin, son of David, born 1896,

The family of Moshe Polovin, son of David, born 1896; his wife Tzile Polovin-Golberg, daughter of Shlomo, born 1917; his daughter Tzile (?) Polovin, born 1939,

Asher Meirovitz, son of Levi, born 1909,

The family of Yakov Leshzh, son of Yankel (?), born 1895; his wife Lika Leshzh-Finkelshtein, daughter of Motel, born1904; her mother Dveire-Chane

Finkelshtein-Maltovsky, daughter of Yudel, born 1861,

The family of David Lapinsky, son of Yankel, born 1874; his son Berl Lapinsky, born 1904; daughters Feige, born 1900 and Yese, born 1908;

Referring to additional sources investigating their banishment43 44, a few more of Jurbarkas's Jews should be added to this list:

The family of E. Geselovitz: his wife Tzipa, daughter of Avraham, born 1890; his daughter Bete, born 1915,

The daughter of J. Leshzh, Hanna, born 1927,

The children of M. Polovin: son Faivel, born 1937; his daughter Gita, born 1935,

Rachel Shugam, daughter of Leon, born 1904 with her children Yankel, born 1920; Kushel, born 1924; Sheitele born 1927; Lina, born 1940. Although he was the head of this family, Mr. Shugam was not mentioned in these sources, he was also oppressed.

Zalman Kaplan, a Jurbarkas Jew living in Vilnius, pointed out the exiled Grinberg family members: Motel Grinberg, son of Zalman, born 1864; his second wife Ema, his daughter in law Zhene and his son Robert, born 192845.

Speaking about all Jurbarkas's citizens, we may suppose that in the wagons taking them to exile on June 14, 1941 there were no less then 60 people46 and among them 29 Jews.

In this part of this thesis many Jewish names and family names have been mentioned, but almost none of their special vocations, such as merchants, teachers, coachmen etc. This is important, because {note added in editing by Joel Alpert: it was due to that fact that} all of them or their offspring were shot during those few months in 1941.

Every name and family name belonged to an individual human being. It is a fact that in history a person often becomes a mere number. For this reason it is important to know who the Jews were who lived in Jurbarkas on the eve of the German occupation.

The Encyclopedia of Lithuania indicates that in 1940 the town's population numbered 5,400 inhabitants, of them 42%, about 2,300, Jews47. The data of the Central Lithuanian State Archive (LCVA) show different numbers: ."..according to the registration of the citizens on December 26, 1940, there were within the boundaries of Jurbarkas 4,439 people, of them 1319 Jews, i.e. 29.7%48." C. Jofe refers to the number of 2,500 Jews. From the Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities in Lithuania published in Israel one learns that in 1941 2,000 Jews (600 Families)49 lived in Jurbarkas.

2.1 Events in June 1941

In 1941 Jurbarkas was about 10 kilometers distance from the German border. On June 22, 1941 the war between Germany and the Soviet Union began and on that same day the German army entered the town at 8 o'clock in the morning. Jurbarkas's Jews quickly felt the changes of the new order.

After the German occupation of Lithuania, local government authorities were established in the provinces. All the former functionaries from the time of the Lithuanian Republic returned to their previous jobs, this being done in accordance with orders of the Temporary Government of Lithuania, but local initiative was important in establishing institutions of self-government, committees, police. These institutions, established de facto, were later legalized de jure, mostly without any changes50.

Jurgis Gepneris, an elderly Jurbarkas citizen acquainted with every resident of the town and fluent in Lithuanian, Russian, German, Polish and Yiddish, again became Mayor of Jurbarkas. On the order of Tchaponsas, the commander of the town, Mykolas Levickas was appointed head of Police on June 24, 1941 and thereafter. He organized a group of policemen, composed mainly of former policemen and soldiers; an auxiliary police company was also established in sufficient numbers for defense purposes, from which members from the civilian security units were recruited 51. During the years 1941 to 1943 Romualdas Levickas served in the Jurbarkas Gestapo and wore an SS uniform.

Jurbarkas was inside the 25-kilometer zone operated by the Gestapo of Tilzit. Among the Germans arriving from Tilzit as SD agents were the officials in charge Grigalavicius, Voldemaras Kriauza, Richardas Sperbergas, Oskaras Sefleris and Karstenis52. The Germans played the managerial role, but the responsibility of the local executors for the fate of the Jews is indisputable.

The first Jewish victims in Jurbarkas apparently were the Es brothers. In a letter written by J. Gepneris on January 6, 1941 to the principal of the Raseiniai District it was said that "at this time there was no registration of those killed, but according to unofficial reports two Jews (the Es brothers) were killed during the shooting in the town"53. I wrote "apparently", because in another document J. Gepneris wrote to the Commissioner of the department about the victims in Raseiniai, that in Jurbarkas " no people became invalids or were killed by German weapons"54. On the first days of the occupation the Germans conducted themselves in a "calm" manner, in order to convince the Jews to obey the orders of the government and not to frighten them. One day a German took Chatzkel Jofe55, Leib Meigel and Leib Karabelnik to a nearby abandoned beer factory, ordered them to dig a hole, to undress and kneel by the side of the hole. Stepping back about ten steps, he used an automatic weapon to shoot over their heads. After that he approached them laughing, offered them cigarettes and released them, saying, that Germans do not shoot people. On their return they told their families and neighbors everything. This had a soothing effect, but nevertheless the Jews instinctively felt great anxiety and fear56. These events happened during the very first days, but soon the murder of the Jews started, although not yet the mass murders. Mykolas Levickas, during investigation, admitted "the first shooting of Jews took place on the fourth day of the German occupation. The perpetrators were Germans SS members, the place - the Jewish cemetery. How many were shot - I don't know"57. Witness J. Keturauskas testified to these facts: "One night at the end of June 1941, policemen V. Ausiukaitis and V. Muleikas went to carry out a special task, from which they returned with many valuables." Later, in the summer of 1941, J. Keturauskas had an opportunity to speak with V. Muleikas. He told him that during that night, together with V. Ausiukaitis, they took part in the shooting of Jews and Soviet activists, and for this they got 3,000 Mark58. Witness P. Mikutaitis related: "I saw (policeman) Kairaitis rushing up the street to a Jew whom I knew, whose first name was Yoshke, I have forgotten his second name, arrested him and took him to the Ghetto. Yoshke was about 60 years old, did not work anywhere and lived with relatives. He was kept in the Ghetto for three days and then shot in the Jewish cemetery"59.

Those events had occurred by the end of June. J. Bogdanskis also reported that the chief of police ordered him and P. Greiciunas to arrest the Jewish doctor B. Raichman and about a week later, on July 3rd, the doctor was shot to death60.

2.2 Events in July 1941

On July 3, 1941, a Thursday afternoon, in the office of J. Gepneris the Mayor of the town, the first Jewish mass extermination was decided upon, to be carried out in the Jewish cemetery61. A group of 40 Gestapo men62 arrived in the town, and together with the local policemen began to round up Jewish men, pulling them out of their houses or their places of work. N. Bregovsky the pharmacist was arrested in his pharmacy in similar manner by policemen K. Almonaitis, P. Kairaitis and M. Urbonas, who also performed "a personal search" on him. N. Bregovsky was led through the town63wearing his white gown. (By the way, the policemen exploited these situations - when arresting a Jew they would steal some of his valuables. For example, A. Dravenikas, who worked in the Jurbarkas police as an interpreter, was arrested by the Germans and imprisoned for two months in Siauliai prison because of "stealing a lot of Jewish property, with which he afterwards speculated" 64). The policemen gathered up groups of about 30 Jews and led them to the police station. Policeman P. Krescinas, the leader of one of these groups which included the Most family, snatched a little child from Most's hands and banged him down onto the road, while at the same time Most himself was pushed forward. Jewish women picked up the child, but they were also shot later. The above mentioned policeman arrested many Jews: Karabelnik, Michelson, the brothers Most and others65. A large empty shed was filled with people, who had been evicted from their homes to the market place. By one o'clock about 300 Jews were gathered there as well as several tens of Soviet activists66. Lacking the required number, 60 more Jews and three women with children, who did not want to be separated from their husbands (the fathers of their children), were brought along. Upon the command: "One step to the left - we shoot! One step to the right - we shoot! One word - we shoot! March!" the column moved in the direction of the cemetery. During the first "actions" a column of about 350 was assembled, three in line, who were then driven to their death. At the end of these columns there would be a few motor cars. The first car held the machine guns, Germans sat in the others, and a car with shovels67 brought up the rear. On that day policemen K. Almonaitis and A. Dravenikas found Most and his son hiding in the kitchen garden. They were torn away from their family and pushed into the death column68. The town's doctor J. Karlinsky was shot as an enemy of the (German) Reich. A Lithuanian doctor, A. Antanaitis, tried to save him, asking the German in charge of the execution to free the doctor from the column since he was needed as a specialist, but the SS man struck A. Antanaitis several times with his stick and threatened to push him too into the column of the condemned. Doctor J. Karlinsky even turned to the chief of the Auxiliary Police Mykolas Levickas whom he had treated and cured. But Mykolas Levickas made a helpless gesture with his hands and, turning away, shouted "Forward!"69. Those Jews who had been driven to the cemetery earlier, had already dug a long trench, and were to dig three more later on. The people arriving now (who were not made to dig, because there were not enough shovels for all) were ordered to break branches from the trees in order to camouflage this place from the road and the town. After finishing this task, the condemned were ordered to beat one another "as much as possible, and whoever refused to do so, would be whipped to death." Nobody moved; nobody raised a hand. Then Jankel Rizman was ordered to climb onto a nearby pear tree and chirp like a lark. He climbed to the top of the tree, shots rang out and Yankel's body fell through the branches70. Emil Max, who had served in the German Army during the First World War and had been decorated with the" Iron Cross", was among the Jews. Standing at the side of the trench, he took hold of a German policeman and tried to throw him into the trench, but a shot "silenced" Max 71. The story of witness Narjauskaite72 confirmed of Chayim Jofe's reports: " At the cemetery the condemned were ordered to break branches from the trees, to dig trenches and to beat each other. The actual shooting was carried out by Germans from the "Dead Head" battalion, the Lithuanians guarded the site. The shooting took place at 4 o'clock in the afternoon, before which the condemned were tortured, and the moaning and crying was even heard in Jurbarkas"73. Several tens of Lithuanians were among those murdered there - communists, comsomols, trade union activists and the Jurbarkas sculptor Vincas Grybas. Some people found themselves alive in the trench, managed to scramble out and escape, among them Antanas Leonavicius74, Povilas Striaukas75 and Abel Vales76. Also Leizer Michailovsky survived this "action", but by different means. When in the death column march, he walked last in line and managed to escape, at the beginning to "some ditch where he hid", later Lithuanian peasants harbored him77.

After the "action" of the men on July 3, 1941, the Jurbarkas occupation authority ordered all elderly Jews to register every morning and evening with the police department. On July 21, 1941, 45 aged men were detained during registration. They were put on carts and each was given a shovel. The official version was that they were going to Raseiniai for a health check up, after which those not fit for physical work would be brought back, whereas the others would be left in Kalnujai to repair a gravel road. "The carts started to move. Rotuliai, Antkaniskiai, Molyne, the small towns of Skirsnemune (already "cleansed" of the few local Jews), Zvyriai, Siline ...passed out of sight. On arrival in Kalnujai, the policemen ordered the Jews to write letters to their families. Leading them farther away from the road and the individual farms, they were ordered to dig a "gravel pit." The men dug slowly, knowing what awaited them, and for that the policemen beat and kicked them. The carrier David Portnoy (whose 12 year old daughter was raped) came to blows with a Lithuanian, called on the other Jews to take the shovels and attack"78. But the end was predetermined and final - all 45 Jews were shot.

From a document dated July 23, 1941 written by the town's mayor J. Gepneris to the Raseiniai district office in connection with the population survey, we learn how many Jews still remained in alive Jurbarkas at this date:" They numbered 1,055 Jews, including 25 children of up to two years old, 39 children aged two to four and 46 children from four to six years old"79.

On of July 25, 1941 the occupation authorities ordered the Jews to tear down the wooden synagogue and with trembling hands they obeyed the order. A group of spectators {Lithuanian Non-Jews} quickly gathered near the synagogue; some of them shrugged their shoulders, being afraid to voice their protest or to show it by the look on their faces. Others looked intently at how the Gothic style roof, the wooden walls, the interior carved decorations were being torn down, and some more active spectators hurried to take parts of those decorations home. After the synagogue had been destroyed, the Jews were ordered to dance and sing. Soon thereafter, the small building situated near the wooden synagogue that had been used as a poultry slaughterhouse was also destroyed. While tearing this building down and cleaning the plates full of blood (which the Germans, apparently, used for some other purposes later on), the Jews dirtied themselves with the blood of the poultry and feathers stuck to their garments. After this work the Jews were ordered to march in formation to the Nemunas River in order to clean up. Arriving by the river, a new order was given: to wade waist deep into the water and then to wash. People who tried to resist were kicked, beaten and pushed into the water by force. The Lithuanians did the beating, while the Germans took photographs. The Jews were cruelly tortured, such as being scalped, and their bodies combed with a sharp iron rake80.

On the following day, July 26, 1941, this vicious mockery of human suffering continued, and this time the victim chosen was the elderly Jurbarkas Cantor Alperovitz. He was a tall, corpulent, gray-headed man, who had graduated from a conservatory in Germany and composed music. A Lithuanian policeman pulled him out of his house on Butchers Street, tied a brick to his beard and led him through the streets, while the Germans took photographs81. Later Cantor Alperovitz was cruelly murdered together with others who remained alive from previous "actions."

On July 27, 1941, 18 Jurbarkas citizens were shot, but it is not clear how many of them were Jews. Policeman P. Bakus confessed that he shot Zilber82 himself.

On the morning of July 28, 1941, (a Shabbath), an order was given to weed some grass. On the same day at 4 p.m., all Jewish books had to be delivered to the site of the ruined synagogue. Jurbarkas Rabbi Chayim Rubinstein brought his books and writings on a handcart. At 5 o'clock the Torah scrolls were ordered to be brought from the brick synagogue (now a three-story dwelling) and the other smaller synagogues (there were five of them) and put on top of the books already piled up. Petrol was poured over the heap and then ignited. For the religious Jews this was a catastrophe.

On July 29, 1941, another order was proclaimed, "all Jurbarkas Jews were to gather beside the town's library," and warned that "anyone who did not appear would be found in any case (with the help of Lithuanian collaborators, of course) and shot." The Jews gathered and were drawn up three in line. Three elderly men were given the bust of Stalin taken from the library, pictures of the Soviet leaders were put into the hands of the women, and then they were ordered to march through the streets of Jurbarkas. The procession was led by Mykolas Levickas, who was assisted by policemen P. Budvinskas, J. Kilikevicius and others. The procession turned in the direction of Nemunas, where a group of spectators had already gathered, and the spectacle began. The Jews put Stalin's bust on a previously arranged table, while all the others stood around. A policemen ordered Fridman (formerly a well known artist) to read a text abusing and slandering the Jewish nation, after which a bonfire was lit into which the Jews threw all the pictures they had brought as well as Stalin's bust. Again they were ordered to sing and dance, and again the Germans photographed83 the spectical At the end of July the chief of police P. Mockevicius summoned policemen V. Almonaitis, P. Kairaitis and J. Marcinkus, ordering them to shoot three elderly (50 to 70 years old) Jewish men from the Ghetto. Each of the Jews were given a shovel and then driven in the direction of Smalininkai. At the seventh kilometer along the road leading from Jurbarkas to Smalininkai, the group turned to the right and walked about one kilometer into the heart of the forest, where the policemen forced the men to dig a hole for themselves, about 1.5 m deep. The condemned men were made to stand at the edge of the hole and then the policemen shot at them from a distance of 50 m. Every policemen shot one bullet at his victim. The shovels they left in the forest. They did not bother to take the clothes of these elderly men, as they were dressed84 rather poorly.

The protocol of J. Grybas' investigation was similar. Not only in this, but also in other investigation protocols it could be clearly evident, that the investigator was more interested in the fate of Soviet activists than in the Jews (inspite of the fact that they were also Soviet citizens). J. Grybas hid from the occupation authorities in a forest not far from Jurbarkas, and four times he witnessed the policemen drive Jews to be shot in large groups of about 100 people. After the words: " I secretly crawled near those places and saw how Jews were shot", the investigator stopped J. Grybas and changed the subject, asking about events after the war, not going into the details of who had shot, or when and where the shooting occurred85.

2.3 Events in August 1941

August, actually Tuesday, August 1, 1941, started with an "action" of elderly women, children and the newborn, the younger and healthy women still being kept back for work. The arrested women were driven into the yard of the elementary school "Talmud-Torah" and in the evening they were ordered to stand in line two-by-two. It was difficult to obey the German order because children got in the way everywhere, and pushing started, with beating and shouting. The pits had been readied beforehand and the shooting took place at night (at the seventh kilometer on the road between Jurbarkas and Smalininkai). There was great panic, the laughing and crying of women who had gone crazy was heard. Not all the women were killed, as some fell into the pit alive or were only wounded. Policemen split the heads of the small children on trees in order to save bullets.

The events of August became known from the file of policeman P. Kresciunas: "At 2 o'clock at night two carts arrived near the Ghetto, and we dragged about 20 Jews into the carts. We drove them six to seven kilometers in the direction of Smalininkai near the village of Kalnenai, having told them that they were going to work in Germany. Then some of us drove the Jews into the forest, whereas the others stayed on the road to guard. After 10 minutes shots were heard. V.Ausiukaitis arrived and ordered us four men to go into the forest. Four to five Jews were still alive and we were ordered to shoot them. If we did not participate in the shooting, he would tell the others about it. I (Kresciunas), P. Greceiunas, B. Angeleika and S. Sibaitis did the shooting. Whether I killed my Jew I don't know, as it was dark. We, the four of us, returned to Jurbarkas on one cart and the others remained in the forest. After a few days V. Ausiukaitis called me, ordering me to proceed to the police station, where V. Ausiukaitis, S. Gylys, P. Bakus, M. and R. Levickai, P. Greiciunas, S. Sibaitis, B. Angeleika, Narvydas, K. Kilikevicius, Rimkus and three Germans were already present. Everyone got a rifle, and we were told to accompany the remaining twelve Jews. Again we went into the same forest and again we four watched on the road. After 10 to 15 minutes shots were heard..."86

In a document from August 21, 1941, in which the chief of the Raseiniai district was informed of the number of Jewish residents within the boundaries of Jurbarkas, these data were given: " Number of Jews - 684; working on the road - 64"87 . The list of people in the liberal professions dated August 7, 1941, included these Jews: Mrs. Miryam Kopelov (dentist), Miss Gita Zaveliansky (midwife)88 . The list of specialist workers from August 28, 1941 included Yerachmiel Shmulovitz (tailor) and Shepsel Maister (tailor)89.

2.4. Events in September 1941