Wroclaw, Poland

Wrocław

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

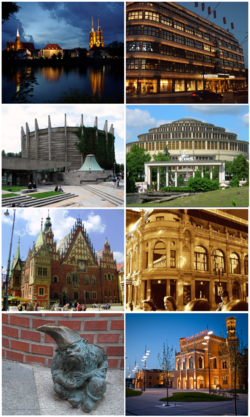

Top to bottom, left to right: Ostrów Tumski by night, Renoma mall, Rotunda of Racławice Panorama, Centennial Hall, City Hall, Monopol Hotel, Wrocław's dwarfs, Main Station

Flag

Motto: Wrocław – Miasto Spotkań / Wrocław – the meeting place

Coordinates: 51°6′28″N 17°2′18″E

city county

Established

10th century

City rights

1242

Government

• Mayor

Area

• City

292.92 km2 (113.10 sq mi)

Elevation

105-155 m (−400 ft)

Population (2012)

• City

631,188[1]

• Metro

1,164,600

• Demonym

Vratislavian, Wrocławster

• Summer (DST)

Postal code

50-041 to 54-612

+48 71

DW

Website

Wrocław is the historical capital of Silesia, and today is the capital of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship. At various times it has been part of the Kingdom of Poland, Bohemia, the Austrian Empire, Prussia, and Germany; it has been again part of Poland since 1945, as a result of border changes after World War II. Its population in 2011 was 631,235, making it the fourth largest city in Poland.

Wrocław was the host of EuroBasket 1963, FIBA EuroBasket 2009, and UEFA Euro 2012; it will host the 2014 FIVB Men's Volleyball World Championship and, in 2017, the World Games, a competition in 37 non-olympic sport disciplines. The city has been selected as a European Capital of Culture for 2016.

Etymology

The city's name was first recorded as "Wrotizlava" in the chronicle of German chronicler Thietmar of Merseburg, which mentions it as a seat of a newly installed bishopric in the context of the Congress of Gniezno. The first municipal seal stated Sigillum civitatis Wratislavie. A simplified name is given, in 1175, as Wrezlaw, Prezla or Breslaw. The Czech spelling was used in Latin documents as Wratislavia or Vratislavia. At that time, Prezla was used in Middle High German, which became Preßlau. In the middle of the 14th century the Early New High German (and later New High German) form of the name, Breslau, began to replace its earlier versions.

The city is traditionally believed to be named after Wrocisław or Vratislav, often believed to be Duke Vratislaus I of Bohemia. It is also possible that the city was named after the tribal duke of the Silesians or after an early ruler of the city called Vratislav.

The city's name in various other languages is: Hungarian: Boroszló, Czech: Vratislav, German: Breslau, Hebrew: ורוצלב (Vrotsláv), Yiddish: ברעסלוי (Brasloi), Silesian German: Brassel, and Latin: Vratislavia or Budorgis[2] or Wratislavia.[3] The city's name in other languages is available at the list of names of European cities.

Persons born or living in the city are known as "Vratislavians" (Polish: Wrocławianie).

History

Main article: History of Wrocław

The city of Wrocław originated as a Bohemian stronghold at the intersection of two trade routes, the Via Regia and the Amber Road. The name of the city was first recorded in the 10th century as Vratislavia, possibly derived from the name of a Bohemian duke Vratislav I. Its initial extent was limited to Ostrów Tumski (Cathedral Island, German: Dominsel).

Middle Ages

The Medieval Polish chronicle Gallus Anonymus written in the years 1112-1116, put Wrocław along with Kraków and Sandomierz as one of the three major capitals of the Polish Kingdom.

During Wrocław's early history, its control changed hands between Bohemia (until 992, then 1038–1054), the Kingdom of Poland (992–1038 and 1054–1202), and, after the fragmentation of the Kingdom of Poland, the Piast-ruled duchy of Silesia. One of the most important events in those times was the foundation of the Diocese of Wrocław by the Polish Duke (from 1025 king) Bolesław the Brave in 1000. Along with the Bishoprics of Kraków and Kołobrzeg, Wrocław was placed under the Archbishopric of Gniezno in Greater Poland, founded by Otto III in 1000, during the Congress of Gniezno. In the years 1034-1038 the city was affected by pagan reaction.[4]

The city became a commercial centre and expanded to Wyspa Piasek (pl) (Sand Island, German: Sandinsel), and then to the left bank of the River Oder. Around 1000, the town had about 1,000 inhabitants.[5] By 1139, a settlement belonging to Governor Piotr Włostowic (a.k.a. Piotr Włast Dunin) was built, and another was founded on the left bank of the River Oder, near the present seat of the University. While the city was Polish, there were also communities of Bohemians, Jews, Walloons[4] and Germans.[6]

In the first half of the 13th century Wrocław became the political centre of the divided Polish kingdom.[7]

Church of St Giles, built 1241-42

The city was devastated in 1241 during the Mongol invasion of Europe. While the city was burned to force the Mongols to withdraw quickly, most of the population probably survived.[8]

After the Mongol invasion the town was partly populated by German settlers[9] who, in the following centuries, would gradually become its dominant ethnic group; the city, however, retained its multi-ethnic character, a reflection of its position as an important trading city on the Via Regia and the Amber Road.[10]

With the influx of settlers the town expanded and adopted in 1242 German town law. The city council used Latin and German, and "Breslau", the Germanized name of the city, appeared for the first time in written records.[9] The enlarged town covered around 60 hectares, and the new main market square, which was surrounded by timber frame houses, became the new centre of the town. The original foundation, Ostrów Tumski, became the religious center. The city adopted Magdeburg rights in 1261, and joined the Hanseatic League in 1387. The Polish Piast dynasty[11] remained in control of the region, but the right of the city council to govern independently increased.

In 1335, Breslau, together with almost all of Silesia, was incorporated into the Kingdom of Bohemia, then a part of the Holy Roman Empire. Between 1342 and 1344, two fires destroyed large parts of the city.

In June 5, 1443 the city was affected by an earthquake of the strength of at least 6 degrees on the Richter scale, which destroyed or seriously damaged many buildings in the city.

In 1474 the city left the Hanseatic League.

Renaissance, Reformation and Counter-Reformation

Breslau in the 17th century

City Towers in 1736

The Protestant Reformation reached Breslau in 1518 and the city became Protestant. However, from 1526 Silesia was ruled by the Catholic House of Habsburg. In 1618, Breslau supported the Bohemian Revolt out of fear of losing the right to freedom of religious expression. During the ensuing Thirty Years' War, the city was occupied by Saxon and Swedish troops, and lost 18,000 of 40,000 citizens to plague.

The Austrian emperor brought in the Counter-Reformation by encouraging Catholic orders to settle in Breslau, starting in 1610 with the Franciscans, followed by Jesuits, Capuchins, and finally Ursulines in 1687. These orders erected buildings which shaped the city's appearance until 1945. At the end of the Thirty Years' War, however, Breslau was one of only a few Silesian cities to stay Protestant.

The precise recordkeeping of births and deaths by the city of Breslau led to the use of their data for analysis of mortality, first by John Graunt, and then later by Edmond Halley. Halley's tables and analysis, published in 1693, are considered to be the first true actuarial tables, and thus the foundation of modern actuarial science.

During the Counter-Reformation, the intellectual life of the city – shaped by Protestantism and Humanism — flourished, even as the Protestant bourgeoisie lost its role to the Catholic orders as the patron of the arts. Breslau became the centre of German Baroque literature and was home to the First and Second Silesian school of poets.

The Kingdom of Prussia annexed Breslau and most of Silesia during the War of the Austrian Succession in the 1740s. Habsburg empress Maria Theresa ceded the territory in the Treaty of Breslau in 1742.

Napoleonic Wars

Entry of Prince Jérôme to Breslau, January 7, 1807

During the Napoleonic Wars, Breslau was occupied by an army of the Confederation of the Rhine. The fortifications of the city were leveled and monasteries and cloisters were secularised. The Protestant Viadrina University of Frankfurt (Oder) was relocated to Breslau in 1811, and united with the local Jesuit University to create the new Silesian Frederick-William University (Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelm-Universität, now University of Wrocław). The city became the centre of the German Liberation movement against Napoleon, and the gathering place for volunteers from all over Germany, with the Iron Cross military decoration founded by Frederick William III of Prussia in early March 1813. The city was the centre of Prussian mobilisation for the campaign which ended at Leipzig.

Prussia

On October 10, 1854, the Jewish Theological Seminary (Fränckelscher Stiftung) opened. The institution was the first modern rabbinical seminary in Central Europe.

Market Square 1890-1900

Breslau Town Hall 1900

Napoleonic redevelopments increased prosperity in Silesia and Breslau. The levelled fortifications opened space for the city to grow beyond its old limits. Breslau became an important railway hub and industrial centre, notably of linen and cotton manufacture and metal industry. The reconstructed university served as a major centre of sciences, while the secularisation of life laid the base for a rich museum landscape. Johannes Brahms wrote his Academic Festival Overture to thank the university for an honorary doctorate awarded in 1881.

In 1821 (Arch)Diocese of Breslau was disentangled from the Polish ecclesiastical province (archbishopric) in Gniezno and made Breslau an exempt bishopric.

German Empire

The Unification of Germany in 1871 turned Breslau into the sixth-largest city in the German Empire. Its population more than tripled to over half a million between 1860 and 1910. The 1900 census listed 422,709 residents. Important landmarks were inaugurated in 1910, the Kaiserbrücke (Kaiser bridge) and the Technische Hochschule (TH), which now houses the Wrocław University of Technology.

The 1900 census listed 5,363 people (just over 1% of the population) as Polish speakers, and another 3,103 (0.7% of the population) as speaking both German and Polish.[12] The population was 58% Protestant, 37% Catholic (including at least 2% Polish)[13] and 5% Jewish (totaling 20,536 in the 1905 census).[12] The Jewish community of Breslau was among the most important in Germany, producing several distinguished artists and scientists.[14]

In 1913, the newly-built Centennial Hall housed the "Ausstellung zur Jahrhundertfeier der Freiheitskriege", an exhibition commemorating the 100th anniversary of the historical German Wars of Liberation against Napoleon and the first award of the Iron Cross.

Weimar

Following World War I, Breslau became the capital of the newly created Prussian Province of Lower Silesia in 1919.

After the First World War the Polish community began holding masses in Polish in the Church of Saint Anne, and, as of 1921, at St. Martin's; a Polish consulate was opened on the Main Square, and a Polish School was founded by Helena Adamczewska (pl).[15]

In August 1920, during the Polish Silesian Uprising in Upper Silesia, the Polish Consulate and School were destroyed, while the Polish Library was burned down by a mob. The number of Poles as a percentage of the total population fell to just 0.5% after the reconstitution of Poland in 1918, when many returned home.[13] Antisemitic riots occurred in 1923.[16]

The city boundaries were expanded between 1925 and 1930 to include an area of 175 km2 (68 sq mi) with a population of 600,000. In 1929, the Werkbund opened WuWa (German: Wohnungs- und Werkraumausstellung) in Breslau-Scheitnig, an international showcase of modern architecture by architects of the Silesian branch of the Werkbund. In June 1930, Breslau hosted the Deutsche Kampfspiele, a sporting event for German athletes after Germany was excluded from the Olympic Games after World War I. The number of Jews remaining in Breslau fell from 23,240 in 1925 to 10,659 in 1933.[17] Up to the beginning of World War II, Breslau was the largest city in Germany east of Berlin.[18]

Rise of Nazis

Known as a stronghold of left wing liberalism during the German Empire,[19] Breslau eventually became one of the strongest support bases of the Nazis, who in the 1932 elections received 44% of the city's vote, their third-highest total in all Germany.[20]

After Hitler's appointment as German Chancellor in 1933, political enemies of the Nazis were persecuted, and their institutions closed or destroyed; the Gestapo began actions against Polish and Jewish students (see: Jewish Theological Seminary of Breslau), Communists, Social Democrats, and trade unionists. Arrests were made for speaking Polish in public, and in 1938 the Nazi-controlled police destroyed the Polish cultural centre.[21][22] Many of the city's 10,000 Jews, as well as many others seen as 'undesirable' by the Third Reich, were sent to concentration camps; those Jews who remained were killed during the Holocaust.[21] A network of concentration camps and forced labour camps was established around Breslau, to serve industrial concerns, including FAMO, Junkers and Krupp. Tens of thousands were imprisoned there.[23]

The last big event organised by the Nazi Sports Body, called Deutsches Turn-und-Sportfest (Gym and Sports Festivities), took place in Breslau from 26 to 31 July 1938. The Sportsfest was held to commemorate the 125th anniversary of the German Wars of Liberation against Napoleon's invasion.[24]

World War II and afterwards

Delegation of German officers walking for negotiations before capitulation of Festung Breslau, 6 May 1945

The ruins of Breslau, photographed on the day of its surrender, 6 May 1945

For most of World War II, the fighting did not affect Breslau. In 1941 the remnants of the pre-war Polish minority in the city, as well as Polish slave labourers, organised a resistance group called Olimp. The organisation gathered intelligence, carrying out sabotage, and organizing aid for Polish slave workers. As the war continued, refugees from bombed-out German cities, and later refugees from farther east, swelled the population to nearly one million,[25] including 51,000 forced labourers in 1944, and 9,876 Allied PoWs. At the end of 1944 an additional 30,000-60,000 Poles were moved into the city after Nazis crushed the Warsaw Uprising.[26] In February 1945 the Soviet Red Army approached the city. Gauleiter Karl Hanke declared the city a Festung (fortress) to be held at all costs. Hanke finally lifted a ban on the evacuation of women and children when it was almost too late. During his poorly organised evacuation in January 1945, 18,000 people froze to death in icy snowstorms and −20 °C (−4 °F) weather. By the end of the Siege of Breslau, half the city had been destroyed. An estimated 40,000 civilians lay dead in the ruins of homes and factories. After a siege of nearly three months, Hanke surrendered on 6 May 1945, days before the end of the war.[27] In August the Soviets placed the city under the control of German anti-fascists.[28]

Along with almost all of Lower Silesia, however, the city became part of Poland under the terms of the Potsdam Conference. The Polish name of "Wrocław" was declared official. There had been discussion among the Western Allies to place the southern Polish-German boundary on the Glatzer Neisse, which meant post-war Germany would have been allowed to retain approximately half of Silesia, including Breslau. However, the Soviets insisted the border be drawn at the Lusatian Neisse farther west.

In August 1945 the city had a German population of 189,500, and a Polish population of 17,000; that was soon to change.[28] Almost all of the German inhabitants fled or were forcibly expelled between 1945 and 1949 and were settled in Allied Occupation Zones in Germany. A small German minority remains in the city,[29] although the city's last German school was closed in 1963. The Polish population was dramatically increased by the resettlement of Poles during postwar population transfers (75%) as well as during the forced deportations from Polish lands annexed by the Soviet Union in the east region, many of whom came from Lviv (Lwów).

Wrocław is now a unique European city of mixed heritage, with architecture influenced by Bohemian, Austrian and Prussian traditions, such as Silesian Gothic and its Baroque style of court builders of Habsburg Austria (Fischer von Erlach). Wrocław has a number of notable buildings by German modernist architects including the famous Centennial Hall (Hala Stulecia or Jahrhunderthalle) (1911–1913) designed by Max Berg.

Wrocław - flood 1997

In July 1997, the city was heavily affected by a flood of the River Oder, the worst flooding in post-war Poland, Germany and the Czech Republic. About one-third of the area of the city was flooded.[30] An earlier equally devastating flood of the river took place in 1903.[31] A small part of the city was also flooded during the flood in 2010.

Tourism

Centennial Hall in Wrocław

Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List

The Hall

Type

Cultural

i, ii, iv

Reference

Inscription history

Inscription

2006 (30th Session)

The Tourist Information Centre (Polish: Centrum Informacji Turystycznej) is located on the Market Square in building No.14.

On the market there is free wireless Internet (Wi-Fi).

Landmarks and points of interest

Ostrów Tumski is the oldest part of the city of Wrocław. It was formerly an island (ostrów in Old Polish) known as the Cathedral Island between the branches of the Oder River, featuring the Wrocław Cathedral built originally in the mid 10th century. The 13th century Main Market Square (Rynek) prominently displays the Wrocław Town Hall. In the north-west corner of the market square there is the St. Elisabeth's Church (Bazylika Św. Elżbiety) with its 91,46 m tower, which has an observation deck. North of the church are the Shambles with Monument of Remembrance of Animals for Slaughter (pl). At south-west corner of the market square there is the Salt Square (now a flower market). Close to the square, between Szewska and Łaciarska streets, there is the St. Mary Magdalene Church (Kościół Św. Marii Magdaleny) established in the 13th century.

The Centennial Hall (Hala Stulecia; German: Jahrhunderthalle) designed by Max Berg in 1911–1913 is a World Heritage Site inscribed by UNESCO in 2006.

The National Museum at pl. Powstańców Warszawy, one of Poland's main branches of the National Museum system, holds one of the largest collections of contemporary art in the country.[33]

Other points of interest include:

-

•Multimedia Fountain - are the most attractive night special programs

-

•Zoo - The oldest and largest (in terms of the number of animals) Zoo in Poland

-

•Botanical Garden in Wrocław (pl) - founded 1811

-

•Municipal Stadium - UEFA Euro 2012 arena

-

•Panorama Racławicka ("Racławice Panorama")

-

•Wrocław Palace in which now houses the Wrocław City Museum

A popular way of sightseeing the city is sailing the small passenger vessels floating on the Oder river. The nearby Ślęża mountain is a frequent destination for tourists.

Education

Wrocław University of Technology - Faculty of Architecture

Wrocław is the third largest educational centre of Poland, with 135,000 students in 30 colleges which employ some 7,400 staff.[34]

List of ten public colleges and universities:

-

•Wrocław University (Uniwersytet Wrocławski):[35] over 47,000 students, ranked fourth among public universities in Poland by the "Wprost" weekly ranking in 2007[36]

-

•Wrocław University of Technology (Politechnika Wrocławska):[37] over 40,000 students, the best university of technology in Poland by the "Wprost" weekly ranking in 2007[38]

-

•Wrocław Medical University (Uniwersytet Medyczny we Wrocławiu)[39]

-

•University School of Physical Education in Wrocław (pl)[40]

-

•Wrocław University of Economics (Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny we Wrocławiu)[41] over 18,000 students, ranked fifth best among public economic universities in Poland by the "Wprost" weekly ranking in 2007[42]

-

•Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Sciences (Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy we Wrocławiu):[43] over 13,000 students, ranked third best among public agricultural universities in Poland by the "Wprost" weekly ranking in 2007[44]

-

•Academy of Fine Arts in Wrocław (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych we Wrocławiu),[45]

-

•Karol Lipiński University of Music (Akademia Muzyczna im. Karola Lipińskiego we Wrocławiu)[46]

-

•Ludwik Solski Academy for the Dramatic Arts, Wrocław Campus (Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Teatralna w Krakowie filia we Wrocławiu)[47]

-

•The Tadeusz Kościuszko Land Forces Military Academy (Wyższa Szkoła Oficerska Wojsk Lądowych)[48]

Economy

Sky Tower - the residential complex, office and commercial space and recreation

FagorMastercook main building

Wrocław's industry manufactures buses, trams, railroad cars, home appliances, chemicals and electronics. The city houses factories and development centers of many foreign and domestic corporations, such as WAGO ELWAG, Siemens, Nokia Siemens Networks, Volvo, HP, IBM, Google, Opera Software, QAD, Bombardier Transportation, DeLaval, Whirlpool Corporation, Bosch, WABCO, FagorMastercook, Tieto, PPG Deco Poland and others. The offices of multiple major Polish companies, including Getin Holding, Akwawit-Polmos Wrocław, Telefonia Dialog, Gazoprojekt, MCI Management, Protram, Selena, Koelner, AB SA, Impel, Kogeneracja SA, EKO Holding are located there as well.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the city has had a developing high-tech sector.

Many high-tech companies are located in the Wrocław Technology Park, such as Baluff, CIT Engineering, Caisson Elektronik, ContiTech, Ericsson, Innovative Software Technologies, IT-MED, Mitsubishi Electric, Maas, IT Sector, Technology Transfer Agency Techtra, Vratis, PGS Software and IBM. In Biskupice Podgórne (Community Kobierzyce) there are factories of LG (LG Display, LG Electronics, LG Chem, LG Innotek), Dong Seo Display, Dong Yang Electronics, Toshiba and many other companies, mainly from the electronics and home appliances sectors.

The following banks have their headquarters in Wrocław: Crédit Agricole Bank of Poland, Bank Zachodni WBK, Euro Bank, Santander Consumer Bank; as well as financial and accounting centers: Volvo, Hewlett-Packard, KPIT Cummins, UPS, GE Money Bank, Credit Suisse. The city is home to the largest number of leasing companies and debt collection in the country, including the largest European Leasing Fund, there is also a headquarters of AmRest, a franchisee network of KFC, Pizza Hut, Burger King and Starbucks. Wrocław is a major center for the pharmaceutical industry: U.S. Pharmacia, Hasco-Lek, Galena, 3M, Labor, S-Lab, Herbapol, Cezal.

In February 2013, Qatar Airways launched its Wrocław European Customer Service.

Closely tied to Wrocław are Bielany Retail Park and Bielany Trade Center, located in Bielany Wrocławskie.

Due to the proximity of the borders with Germany and the Czech Republic, Wrocław and the region of Lower Silesia is a large import and export partner with these countries.

Transport

Wrocław is skirted on the south by the A4 motorway, which allows for a quick connection with Upper Silesia, Kraków and further east to Ukraine, and Dresden and Berlin to the west. The A8 motorway (Wrocław ring road) around the west and north of the city connects the A4 motorway with the National road 5 that leads to Poznań, Bydgoszcz and S8 express road that leads to Oleśnica, Łódź, Warsaw and Białystok. Under construction is the eastern part of the ring road.

The city has an International Airport supported by Ryanair, Wizz Air, Lufthansa, LOT and other; the main rail station Wrocław Główny; and, adjacent to the railway station, a central bus station with services offered by PKS, PolskiBus.com, Eurolines and other.

The city has a river port on the Oder.

Public transport in Wrocław includes bus lines and 22 tram lines operated by Miejskie Przedsiębiorstwo Komunikacyjne (MPK, the Municipal Transport Company).[49] Rides are paid for, tickets can be bought above kiosks and vending machines, which are located at bus stops and vehicles. You can also purchase a ticket in electronic form on the phone. Tickets are one-ride or temporary (0,5h, 1h, 1,5h, 24h, 48h, 72h, 168h).

A number of private taxicab firms operate in the city.

Wrocław has a network of bike paths and a bike rental system, Wrocław City Bike.

Religion

Wrocław Cathedral in the oldest district of Ostrów Tumski

Like all of Poland, Wrocław's population is predominantly Roman Catholic; the city is the seat of an Archdiocese. However, post-war resettlements from Poland's ethnically and religiously more diverse former eastern territories (known in Polish as Kresy) and the eastern parts of post-1945 Poland (see Operation Vistula) account for a comparatively large portion of Greek Catholics and Orthodox Christians of mostly Ukrainian and Lemko descent. Wrocław is also unique for its "Dzielnica Czterech Świątyń" (Borough of Four Temples) — a part of Stare Miasto (Old Town) where a Synagogue, a Lutheran Church, a Roman Catholic church and an Eastern Orthodox church stand near each other. Other Protestant churches are also existent in Wrocław and include: Baptist, Pentecostal, Methodist, Adventist and Free Christians.

In 2007, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Wrocław established the Pastoral Centre for English Speakers, which offers Mass on Sundays and Holy Days of Obligation, as well as other sacraments, fellowship, retreats, catechesis and pastoral care for all English-speaking Catholics and non-Catholics interested in the Catholic Church. The Pastoral Centre is under the care of Order of Friars Minor, Conventual (Franciscans) of the Kraków Province in the parish of St Charles Borromeo (Św Karol Boromeusz).

International relations

See also: List of twin towns and sister cities in Poland

Twin towns and sister cities

Wrocław is twinned with:[54]

Partnerships

Gallery

-

•

Famous people

See also: Category:People from Wrocław, List of people from Wrocław, and List of people from Breslau

-

•Đorđe Andrejević-Kun - Serbian and Yugoslav painter

-

•Fritz Haber - chemist, received Nobel Prize in Chemistry

-

•Clara Immerwahr - wife of Fritz Haber, first woman to receive a PhD at University of Breslau

-

•Wojciech Kurtyka - Polish mountaineer

-

•Wanda Rutkiewicz - climber, the first woman on K2

-

•Max Simon - Waffen SS Knights Cross holder

-

•Daniel Speer - author "Ungarischer oder Dacianischer Simplicissimus", one version of Simplicius Simplicissimus

-

•Bartholomäus Stein (de) (1477-1520) - Silesian geographer and historian, head of the cathedral school of the early 16th century. His life's work is the book Descriptio Tocius Silesie et Civitatis Regie Vratislviensis.