Wroclaw, Poland

University of Wrocław

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

An editor has expressed a concern that this article lends undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, controversies or matters relative to the article subject as a whole. Please help to create a more balanced presentation. Discuss and resolve this issue before removing this message. (September 2011)

The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until the dispute is resolved. (September 2011)

University of Wrocław

Uniwersytet Wrocławski

Latin: Universitas Wratislaviensis

Established

1945

Type

prof. dr hab. Marek Bojarski

Students

31 557[1]

Location

Former names

Leopoldina

Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Breslau

Website

University of Wrocław at night

The University of Wrocław (UWr) (Polish: Uniwersytet Wrocławski; German: Universität Breslau; Latin: Universitas Wratislaviensis) is a public, research university located in Wrocław, Poland. It is one of the oldest (established in 1702) collegiate-level institutions of higher education in Central Europe with around 40,000 students at present. The history of the contemporary Polish university begins on August 24, 1945, following the territorial changes of Poland immediately after World War II. It was established primarily by academics from the former University of Lwów, by restoring the building split in two after a severe bombardment. The first lectures were conducted in halls with broken windows.[2] At present, the University of Wrocław is the biggest university in Lower Silesia with over 100,000 graduates since 1945 including some 1,900 scientists many of whom received the highest medals for their contributions to the development of science.[2]

History

Leopoldina

Loepoldina, 1760

Not to be confused with Akademie Leopoldina.

The oldest mention of the university in Wrocław comes from the foundation deed signed on July 20, 1505 by King Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary (also known as Władysław Jagiellończyk) for the Generale litterarum Gymnasium in Wrocław. However, the new academic institution requested by the town council wasn't built because the King's deed was rejected by Pope Julius II for political reasons.[2] Also, the numerous wars and opposition from the Cracow Academy might have played a role. The first successful founding deed known as the Aurea bulla fundationis Universitatis Wratislaviensis was signed two centuries later, on October 1, 1702 by the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I of the House of Austria, King of Hungary and Bohemia.[2]

The predecessor facilities, which existed since 1638, were converted into Jesuit school, and finally, upon instigation of the Jesuits and with the support of the Silesian Oberamtsrat (Second Secretary) Johannes Adrian von Plencken, donated as a university in 1702 by Emperor Leopold I as a School of Philosophy and Catholic Theology with the designated name Leopoldina. On 15 November 1702, the university opened. Johannes Adrian von Plencken also became chancellor of the University. As a Catholic institute in Protestant Breslau the new university was an important instrument of the Counter-Reformation in Silesia. After Silesia passed to Prussia the university lost its ideological character but remained a religious institution for the education of Catholic clergy in Prussia.[citation needed]

Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität

The University of Breslau, 19th century

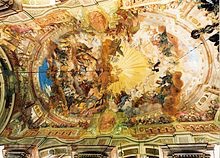

Aula Leopoldina

After the defeat of Prussia by Napoleon and the subsequent reorganisation of the Prussian state, the academy was merged on August 3, 1811, with the Protestant Viadrina University, previously located in Frankfurt (Oder) and re-established in Breslau as the Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Breslau. At first, the conjoint academy had five faculties: philosophy, medicine, law, Protestant theology, and Catholic theology.

Connected with the university were three theological seminars, a philological seminar, a seminar for German Philology, another seminar for Romanic and English philology, an historical seminar, a mathematical-physical one, a legal state seminar, and a scientific seminar. From 1842, the University also had a chair of Slavic Studies. The University had twelve different scientific institutes, six clinical centers, and three collections. An agricultural institute with ten teachers and forty-four students, comprising a chemical veterinary institute, a veterinary institute, and a technological institute, was added to the university in 1881. In 1884, the university had 1,481 students in attendance, with a faculty numbering 131

The library in 1885 consisted of approximately 400,000 works, including about 2,400 incunabula, approximately 250 Aldines, and 2840 manuscripts. These volumes came from the libraries of the former universities of Frankfurt and Breslau and from disestablished monasteries, and also included the oriental collections of the Bibliotheca Habichtiana and the academic Leseinstitut.[citation needed]

In addition, the university owned an observatory; a five-hectare botanical garden; a botanical museum and a zoological garden founded in 1862 by a joint stock company; a natural history museum; zoological, chemical, and physical collections; the chemical laboratory; the physiological plant; a mineralogical institute; an anatomical institute; clinical laboratories; a gallery (mostly from churches, monasteries, etc.) full of old German works; the museum of Silesian antiquities; and the state archives of Silesia.

In the late 19th century, numerous internationally renowned and historically notable scholars lectured at the University of Breslau, Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet, Ferdinand Cohn, and Gustav Kirchhoff among them. According to Polish professor of history Henryk Barycz in the academic year of 1813/1814 Polish youth constituted the majority of students at the University.[3] Following Napoleon's defeat, the decisions made at the 1815 Congress of Vienna ceded the Polish territories of the Duchy of Warsaw to the Kingdom of Prussia establishing the autonomous Grand Duchy of Posen. In contrast to the other 11 provinces of Prussia, neither Duchy of Posen nor West Prussia possessed universities of their own.[4] The University maintained its multiethnic and international character.[5][6] All students, including German, Polish and Jewish, established their own student fraternities.

In 1827 Hieronim Zakrzewski petitioned Prussian authorities to fund University in Poznan during the first meeting of local parliament in Poznań in 1827.[7]

The Prussian government chose to not found universities there because of concerns about creating "bastions of Poledom", but instead to have the Lower Silesian Breslau university also serve the Grand Duchy of Posen (60% Polish majority) and the East Prussian University of Königsberg also serve West Prussia (30% Poles).[4]

Polish student organisations included Concordia, Polonia, and a branch of the Sokol association. Many of the students came from other areas of partitioned Poland. The Jewish students unions were the Viadrina (founded 1886) and the Student Union (1899). Teutonia, a German Burschenschaft founded in 1817, was actually one of the oldest student fraternities in Germany, founded only two years after the Urburschenschaft. The Polish fraternities were all eventually disbanded by the German professor Felix Dahn,[5] and in 1913 Prussian authorities established a numerus clausus law that limited the number of Jews from non-German Eastern Europe (so called Ostjuden) that could study in Germany to at most 900. The University of Breslau was allowed to take 100.[8]

As Germany turned to Nazism, the university became influenced by Nazi ideology. Polish students were beaten by NSDAP members just for speaking Polish.[9] In 1939, all Polish students were expelled and an official university declaration stated, "We are deeply convinced that [another] Polish foot will never cross the threshold of this German university".[10] In that same year, German scholars from the university worked on a scholarly thesis of historical justification for a "plan of mass deportation in Eastern territories"; among the people involved was Walter Kuhn, a specialist of Ostforschung. Other projects during World War II involved creating evidence to justify German annexation of Polish territories, and presenting Kraków and Lublin as German cities.[11]

The University of Wrocław

The University Church, vault

After the Siege of Breslau, the Soviet Red Army took the city in May 1945. The German population fled or was expelled. Wrocław became part of the Republic of Poland. Following postwar border shifts, the Polish Jan Kazimierz University of Lwów, complete with library and Ossolineum was moved from Kresy to Wrocław with thousands of staff, employees and their belongings, because the city of Lwów fell within the Soviet Ukrainian SSR.[12] Many of the buildings were partially destroyed during the defence of the city. Parts of the collection of the university library was burned by soldiers of the Red Army on 10 May 1945, four days after the German garrison surrendered the city.

The first Polish team of academics arrived in Wrocław in late May 1945 and took custody of the university buildings, and started to rearrange the university buildings, which were 70% destroyed. Very quickly some buildings were repaired, and a cadre of professors was built up, many coming from prewar Polish universities in Wilno and Lwów.

The university as known today was originally founded under its current name as a Polish state university by a decree issued on August 24, 1945. Its first lecture was given on November 15, 1945 by Ludwik Hirszfeld. From 1952 to 1989 the University of Wrocław was known as Uniwersytet Wrocławski im. Bolesława Bieruta, after Bolesław Bierut, The First Secretary of the Polish Communist Party.

In 2002 the university celebrated the 300th anniversary of its founding.

Notable alumni and faculty

University of Wrocław, Main Building

Nobel Prize winners from the former German University when it was known as the Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Breslau:

Rectors (presidents) of the University since 1945:

-

•Stanisław Kulczyński (1945–1951)

-

•Jan Mydlarski (1951–1953)

-

•Edward Marczewski (1953–1957)

-

•Kazimierz Szarski (1957–1959)

-

•Witold Świda (1959–1962)

-

•Alfred Jahn (1962–1968)

-

•Włodzimierz Berutowicz (1968–1971)

-

•Marian Orzechowski (1971–1975)

-

•Kazimierz Urbanik (1975–1981)

-

•Józef Łukaszewicz (1981–1982)

-

•Henryk Ratajczak (1982–1984)

-

•Jan Mozrzymas (1984–1987)

-

•Mieczysław Klimowicz (1987–1990)

-

•Wojciech Wrzesiński (1990–1995)

-

•Roman Duda (1995–1999)

-

•Romuald Gelles (1999–2002)

-

•Zdzisław Latajka (2002–2005)

-

•Leszek Pacholski (2005–2008)

-

•Marek Bojarski (from 2008)

Notable students and professors:

-

•Edith Stein (Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross)

Honorary Doctorates