Chapter II

History and our Family

o comprehend what brought the Shanas, Stracovsky and related families to Canada, it is necessary to understand the life they left in Ukrainian Russia at the turn of the 20th century.

How or why our families first got to what is now the independent Ukraine is not known. Jewish history commences in the Middle East. When the Roman Empire conquered Jerusalem in 70 A.D., Jews scattered to the far reaches of the empire, from what is now Portugal to the present Romania. By the 4th and 5th centuries, when the Roman Empire was collapsing, there were Jews throughout Europe, spreading across the continent as major acts of anti-Semitism took place. Until the tenth century most noted events in Jewish history took place in the Middle East. The decline of Babylon around the year 1000 was just about the time that the two great Jewish European centers started in Spain and along the Rhine in Germany. Jewish settlement continued to spread, and by the end of the eighteenth century, 75% of the world's Jewish population was living in Europe.

The early history of some Jews in Ukraine goes back well over 800 years. Kievís central position on the River Dnieper, at the commercial crossroads of Western Europe and the Orient, is known to have attracted Jewish settles from the time the city was founded in the 8th century.

But some historians believe that Jewish history goes back much earlier. They believe that the Khazars, a Turkish tribe that showed up in Ukraine around 400 A.D, had a mass conversion to Judaism in the first decade of the 9th century before they were defeated by the Rus

in 965 A.D., ending the Khazarian Empire. It was the Khazars who founded the city of Kiev, and then lost it to the Rus. According to that theory, the descendants of those Jewish Khazars who were left after their defeat merged with the mass migration of Jews who moved into the Kiev area from western Europe from the 14th to 16th centuries.

Other researchers feel the role of the Khazars on eastern European Jewry was rather minor.

nother recent theory, somewhat but thus far not fully supported by DNA research, suggests that only Jewish males can trace their roots back to the Mid-eastern population of 4,000 years ago. According to this theory, the men who were traders, established local Jewish populations in other parts of the world by marrying local women, and then raising Jewish families.

In any case, whatever theories one believes for the earliest Jewish history, certainly the major migration of Jews to the eastern European areas came at around the end of the 18th century, with the movement actually beginning after Jews were expelled from Spain in the middle ages. That expulsion of Jews set up a migration to Holland and then to other northern European countries. From there it went to Eastern Europe.

Much of the continuous Jewish movement was simply an attempt to stay out of the way of discrimination and brutality. Starting with the First Crusade in 1096, attacks against Jews were a common event. From the 13th to the 15th centuries, Jews were subjected to major expulsions from several countries. In 1290 they were thrown out of England and expelled from France. In the 14th century Jews throughout Europe were blamed for the Black Plague, and were beaten, tortured and killed. Many Jews that were living in Germany at that time migrated east into Poland and Lithuania. This was the great Ashkenazi migration (Germany was known in medieval Hebrew by the biblical name of Ashkenaz.) The Ashkenazi migration accounts for the fact that the Yiddish language has so much German in it. Interestingly, those who discount the theory that the Khazars were also early ancestors of eastern European Jews, point out as one reason that there is no Turkish influence in the Yiddish language.

The Jewish name-tracing scholar and genealogist Alexander Beider believes that eastern European Jews emigrated in the middle ages from three areas: (1) the Rineland in Western Germany (2) Bohemia, now the area of Czechoslovakia, and adjacent Moravia (3)

and to a much less extent, the area of what is now Ukraine according to the Khazarian theory. He feels that although the Yiddish language first developed in the Rhineland, most Polish migrants came from Bohemia and Moravia in what is now the Czech Republic, and then migrated down the Elbe River.

and to a much less extent, the area of what is now Ukraine according to the Khazarian theory. He feels that although the Yiddish language first developed in the Rhineland, most Polish migrants came from Bohemia and Moravia in what is now the Czech Republic, and then migrated down the Elbe River.

Since the Shanas, Stracovsky and related families were Yiddish-speaking

Ashkenazi Jews who

Ashkenazi Jews who spoke Yiddish, like those in our family,

probably migrated east across Germany and into the eastern

areas of Poland that became part of Ukraine.

probably lived in what was Poland before the borders changed and it became Ukraine (see below), they may also trace back to the Bohemia and Moravia areas in earlier times according to that theory.

But almost certainly our Russian-Ukrainian families were Polish families in an earlier period. That is because the city of Kiev, and the area of the four Shanas/Stracovsky shtetls of Brusilov, Kornin, Pavoloch and Popilnia (which range from 60 miles to 80 miles southwest of Kiev) were part of Poland, having been annexed by Poland in the early part of the 16th century. (The word "Ukraine" means borderlands). By the end of the 16th century what is now Ukraine contained 45% of the entire Polish Jewish population. By the 17th century there were 300,000 Jews in Poland, most of whom had come from western Europe in the centuries before.

According to Dr. Neil Rosenstein, a well-know Jewish genealogist, there were only about one million Ashkenazi Jews during the 1500s,

and all Ashenazi Jews today trace back to that million. Rosenstein notes, therefore, that most Ashenazi Jews today are related in some way to Rashi and other noted rabbinical families. In the 16th and 17th centuries, rabbinical families, like European royalty, married among themselves.

All this also means that if you trace back far enough, you will find common relationships between most Ashkenazi Jews today.

rom the 15th to the 19th centuries in Poland, the landowners lived in the manors, the peasants lived in peasant villages and the Jews lived in the shtetls. However many Jews at that time earned their living by managing the large estates of the landowners and nobles. When peasants in the Ukrainian part of Poland rose up against their landlords, they also took their anger out on the Jews who worked for them. In 1648, what was known as "the Golden Age of Polish Jewry" came to an end during the violent Cossack rebellion. The leader, Bogdan Chmielnicki, had aimed to eradicate Judaism in Ukraine. Over 100,000 Jews were killed, and 300 communities destroyed. Many Jews fled Poland, returning back west into Europe. But many others stayed and the Jewish population in Poland continued to grow.

During this period the eastern border of Poland extended quite far into what is present day Russia. The Polish commonwealth itself was comprised of Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine and various other territories. Thus, any Shanas, Stracovsky or related family members in that area at that time were Polish, not Russian.

In 1667, following a two-year war with Poland, the Russians won a major part of Polish Ukraine. The region east of the Dnieper River (which slices through the city of Kiev) had gone to Russia; the western part remained with Poland. Since the Shanas/Stracovsky shtetls of Brusilov, Kornin, Pavoloch and Popilnia, are west of Kiev, they remained in Poland. At the time of the split about 750,000 Jews were on the Russian side.

Arrow indicates area of family shtetls, which after 1792 had switched

from Polish to Russian territory.

he year 1772 marked the first of three partitions of Poland, when more than 620,000 additional "unwelcomed" Jews came under Russian rule. It was the second partition, in 1792-93, that Russia got the Ukraine and the Minsk regions. With that partition the four Shanas-Stracovsky shtetls were now in territories occupied by Russia. By the third partition in 1794 the four towns were well within the borders of Russia. Poland had ceased to exist, and was now split between Prussia, Austria and Russia, where a large number of Jews were. Poland wouldnít regain independence again until 1918.

Why the Shanas-Stracovsky families and most Jews settled in the shtetls around Kiev, rather than the city itself, probably had to do with the cityís history of anti-Semitism. Three years after the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, the small Jewish community living in Kiev was expelled from that city. When that decree was revoked in 1503, Kievís Jewish community was reestablished. However in 1619 the Christian merchants living in Kiev obtained from King Sigismund III a prohibition on permanent settlement of Jews or their acquisition of real estate in the town. That ban was lifted in 1793, and the Jewish community was reestablished. But Jews were still unwanted in Kiev.

The chain of four family shtetls lies about 55 miles from the City of Kiev.

n 1798, after the cityís small Jewish community acquired land for a cemetery, the earlier conflicts began again, with Christians seeking to continuously expel Jews based on King Sigismundís 180-year-old prohibition, coupled with the argument that "holy" Kiev was "profaned" by the presence of Jews. By 1827 Kiev was forbidden to Jews, and although that decree was twice deferred (on the grounds that the expulsion of Jews would worsen Kievís economic conditions), the decree became permanent in 1835. At that point whatever Jews were in Kiev, left the town for good. Jews, including those in the Shanas-Stracovsky and related families, didnít start settling in Kiev again until around 1917, after the Russian Revolution. After the revolution all residence restrictions were abolished, and Jews immediately began streaming into the city.

But from 1791 until the period of the Russian Revolution, Russian Jews throughout all of Eastern Europe became restricted to the area known as the Pale of Settlement. One major reason (in addition to the usual anti-Semitism) is that non-Jewish merchants had been complaining to the government about competition from Jewish merchants. Restricting Jews to a specific area helped eliminate that competition. The Pale included what had been the Polish and Lithuanian gubernii or provinces, the southern Black Sea territories recently conquered from the Ottoman Empire, and a few other provinces later opened to Jewish settlement. By 1800 another 450,000 Jews were in those parts of what was once Poland, and were now ruled by Austria and Prussia. Prior to the late 1700s, Jews pretty much ran their own courts, schools, government, etc. That would change with the Pale of Settlement.

Arrow points to area of Pale of our family shtetls. When Pale

collapsed following the Russian Revolution, members of our

family began moving into Kiev.

By the mid-19th century the Pale had come to include Russian Poland, Lithuania, Belorussia, the Crimea, Bessarabia, and most of Ukraine. There were now hundreds of shtetls of different sizes and shapes spread across the Pale, and in almost all of them the population was 50% to 90% Jewish. All four Shanas-Stracovsky shtetls were in the Ukrainian part of the Pale. Russia felt that Jews were a threat to national and economic interests as well as to Russian Orthodoxy. In all, the Pale of Settlement consisted of 25 provinces, and some five million Jews -- the largest concentration of Jews in the world. As previously noted, they would be confined to that area until the Russian Revolution in 1917. However, during the World War I period about half a million of the Jews living in the Pale would be uprooted and moved eastward.

By the mid-19th century the Pale had come to include Russian Poland, Lithuania, Belorussia, the Crimea, Bessarabia, and most of Ukraine. There were now hundreds of shtetls of different sizes and shapes spread across the Pale, and in almost all of them the population was 50% to 90% Jewish. All four Shanas-Stracovsky shtetls were in the Ukrainian part of the Pale. Russia felt that Jews were a threat to national and economic interests as well as to Russian Orthodoxy. In all, the Pale of Settlement consisted of 25 provinces, and some five million Jews -- the largest concentration of Jews in the world. As previously noted, they would be confined to that area until the Russian Revolution in 1917. However, during the World War I period about half a million of the Jews living in the Pale would be uprooted and moved eastward.

19th century drawing of a Jewish couple from the

Pale of Settlement

Spread of the Hassidic Movement

By 1760 the vast majority of Jews living

around the Kiev area were Hassidic.

Assuming our family was anywhere in

the area of the family shtetls, the chances

are overwhelming we descend from

Hassidic Jews.

lthough there were degrees of religious observance, for centuries the majority of Jews in the Pale followed traditional rabbinic Judaism. Then in the 18th century, two more religious groups emerged. The Hassidic movement, founded by the Bal Shem Tov in the period 1700-1760, looked at rabbinic study as mechanical and formal. Hassidics stressed religious ecstasy and charismatic leadership. The idea was to serve God with joy. The movement spread throughout Eastern Europe from its origins in Podolia, the province just south of Kiev province. Within 120 years of the Bal Shem Tovís death in 1760, 80% of eastern Europeanís Jews were Hassidic. Because the Jewish population in Eastern Europe was so much smaller at that time, most Ashkenazi Jews of today are descendents of Hassidic Jews. The Shanas-Stracovsky and related families, coming from the area that was the heart of the Hassidic movement, must have been Hassidic. Certainly, any of our family members in the area before 1860 were Hassidic. By that date Hassidim were dominant in the area of south-central Ukraine, and the chances are if you were Jewish, you were part of the movement. According to genealogist Raphael Gruber, Jewish names like "Yehuda Leb" and "Zvi Hersh" (both found in the Shanas family) are most likely from Hassidic lineage.

he religious Jewish practices that our grandparents continued once they arrived in Winnipeg reinforces the fact that they came from Hassidic backgrounds. For example, Mildred (Mickey) Gutkin(99), a granddaughter of Harry Shanas(14) could recall that Harry, once in Winnipeg, was one of a small group of disciples of Rabbi Twersky, the Makarover Rov (rabbi from Makarov). This is the kind of title given to a Hassidic rabbi. Twersky lived and had his congregation in a house on the corner of Boyd and Salter Streets, where Mildred and her brother, Leib Shanas(100), whose Hebrew name was Yehuda Leib grew up. Makarov, is a shtetl near Kiev. According to the Shtetl Finder Gazetteer by Chester G. Cohen, the Twersky family Hassidic dynasty began in Makarov with a Nachum Twersky (1805-1851).

The second religious movement was the Jewish Enlightenment or Haskalah. That movement arrived in Eastern Europe from Germany at the end of the 18th century. Its adherents, called Maskilim,

emphasized secular education, assimilation, and a more rational appeal to Judaism. During the Enlightenment, which came after 1860, people tried to obscure their Hassidic backgrounds.

Once in the New World the Shanas, Stracovsky and related families followed neither of those groups to their extremes, and like the vast majority of Jews, instead followed traditional rabbinical Judaism. The knowledge and strict observance of Jewish laws and

customs were an important part of their lives.

During the period of the Pale, there were no innate rights for most Russian citizens, not just Jews. At that time the government granted "privileges" to people, and citizens had to earn their rights. About 90% of the Russian population were surfs and had no right of movement at all. Jews, most of whom were lower middle class (not peasants) were "accorded the privilege" of living within the Pale.

In 1795 a Russian law was passed that the Jews had to

register in towns, although they didn't necessarily live in the towns they registered in. In December, 1804 all Russian Jews were required to have surnames for the first time (early rabbinical families had surnames long before that), and the census of 1811 was probably the first census according to the surnames. Names were taken from places, occupations, looks, etc. Sometimes the authorities would sell the rights to "better names." The name Shanas, pronounced "Shey-nees" in Russia, may have derived from the Yiddish word "shaina" (pretty) or perhaps from the Yiddish "Shamus," a rabbiís assistant. The name Stracovsky certainly came from the town of Stracov (Strokiv), in the region near Kiev our families came from. Perhaps original members of the Stracovsky family were from that town.

(Winnipeg, 1923)

My maternal grandparents, Moses(10) and Rebecca(11) Stracovsky possibly got that surname

because ancestors of Moses trace back to the town of Strociv, which forms a triangle with the

nearby family shtetls of Pavoloch and Polilnia. Jews began acquiring surnames around 1804.

In 1812 Napoleon invaded Russia, and even more Jews headed south toward Ukraine. It was Napoleon who started the modern civil record-keeping systems.

n 1827 Jews in Ukraine first became subject to the military draft. Czar Nicholas I had implemented a policy called "cantonment" in which Jewish boys, from ages 12 to 18 had to receive special instruction, and then begin a regular period of 25 years' army service. While the draft was 25 years for all Russians, many Jewish boys were forcibly taken as early as age 8 and converted to Christianity or killed. The 25-year draft was abandoned in 1856, but not before thousands of Jewish boys had been murdered. Many Jews ran away or did whatever they could to try to avoid the military.

In 1835 a new series of tougher regulations against Jews went into effect. Within five years, Jews were being classified into two groups: "useless" and "useful," with the vast majority falling into the first category. Those considered "useful" were merchants, craftsmen or anybody else who provided a needed service for the general population. "Useless" Jews were subject to the military; "useful" Jews could often escape the draft.

In 1844 town councils began governing the Jewish population and a special "candle tax" was established on Sabbath candles. During the period 1856 to 1881 Czar Alexander II was in power, and the situation for Jews became just a bit more liberal for awhile. Starting in 1859, wealthier Jewish merchants were allowed to live outside the Pale. Then in 1879 Jews with academic degrees could choose to live anywhere. From 1856-73 the military draft was "reduced" to 15 years. (After that, up to the Russian Revolution, it was five years). In that period Jews began migrating south to big cities such as Kiev and Odessa.

till, despite the "liberalization," in the 1870s the anti-Jewish press was in full force; in 1871 a 3-day anti-Jewish riot erupted in Odessa; in 1874 a universal draft began, and all Jewish males had to register. Starting in 1877 Jewish men could no longer serve on juries; and in 1879 ritual murder charges were brought against several Jews in the Caucasus.

The anti-Semitism begin in full force once again in March, 1881, when Czar Alexander was killed by a bomb and the assassination was blamed on the Jews. This, of course, was on top of the

The 1881 assassination of Czar Alexander II set anti-Semitism in full force once again.

"traditional" type of anti-Semitism which blamed Jews for the death of

Christ. Russian anti-Semitism also stemmed from the fact that the czars were considered the head of the Russian Orthodox Church,

and therefore felt an obligation to establish and maintain "the true faith."

One month after the Czarís assassination, the first pogroms started in Ukraine, spreading north in an unsystematic way. Over the

next several years a bloodbath of government-sanctioned pogroms took place. (The word pogrom is Russian, meaning "violent mass attacks.") Most Jews were once again restricted to living in little townlets or shtetls. In May 1882, a program of discriminatory legislation (known as the May Laws) put intolerable restrictions on Jewish life. For example, a quota system in the shtetls prevented the majority of Jews from getting a secondary education. By 1897, when Harry Shanas(14) was in his late 20s and Moses Stracovsky(10) was a late teenager, there were strict limits on Jewish education, and strict restrictions placed on where Jews could live.

By the end of the 19th century, the Russian government became committed to the "Russification" of minorities under its reign. Jews, who until then were had maintained their own language (Yiddish) and their own educational system, were encouraged to speak Russian, attend Russian schools and universities, and generally adopt the Russian culture. This process of "acculturation" continued to accelerate until the revolution of 1905, which transformed Russia into an autocracy from a constitutional monarchy.

lthough most Jews in the Pale were poor, self-employed people, trying to eke out a living as laborers, shopkeepers, peddlers, artisans, etc (most were listed in Russiaís 1897 census as petit bourgeois or "small businessman"), a very few who managed to achieve high positions in business and industry made it big. For example, the names Brodsky, Poliakov and Gunzburg were famous throughout the Pale (and later in the western world). But because the competition for jobs was fierce, most found it hard to make a living. After 1821, unemployment in the Pale was at 30%.

To make economic matters worse, starting around the 1860s the Russian/Ukrainian economy had begun to change. The shtetls were actually market towns where Jews could exchange their services and trades for cash. But the introduction of factories and more modern production techniques changed that market class economy Ė and it happened at a time that the Jewish population was growing enormously.

By the 1880s and 1890s 20% of all Jews in Ukraine were on relief, and shelters were being built for the destitute. One such shelter was located in Berdichev, about 30 miles west of Popilnia and Pavoloch where the Shanas family comes from. In Zhitomir, about 25 miles west of Brusilov and Kornin where the Shanas and Stracovsky family members lived, about one out of every four Jews turned to local Jewish charity for winter fuel. Beggars abounded, and Jewish criminality, prostitution and juvenile delinquency had become real problems.

In reaction to what was happening, the first Zionist movement sprang up among Jewish youth who advocated that national renewal can only be achieved in the land of Israel. But the Zionists were in the minority, and most Jews had more practical concerns, such as putting food on the table. Many looked toward The United States and Canada as the way out.

By 1900 about five million Jews lived in Russian territory, and the anti-Semitic Czarist rulers were trying to find ways to either expel them or contain them in the Pale, which stretched from the Black Sea to the Baltic.

Not all East European Jews lived in shtetls. Jews also inhabited cities (unless specifically banned from a city such as Kiev), rural villages and even some farms. By 1900 more than half of Russia's Jewish population had moved to cities. It should also be noted that Jews were not the only inhabitants of the Pale. Many gentiles lived in shtetls also, although there was little more than routine contact between the two groups.

In 1903, even greater anti-Semitism than was created by the publication of "The Protocols of the Elders of Zion," a fictitious document purporting to contain the Jewish plan for world domination. The document, later proven to be a forgery, was translated in many languages and spread from Russia throughout Europe.

One of the worst outbreaks of violence against Jews came on April 19-20, 1903, exactly three months before Harry Shanas(14) boarded his ship to the New World. In the city of Kishinev, about 250 miles south of our family shtetls, 45 Jews were killed, 586 injured and countless women were raped and children tortured over the two-day period.

Michael Davitt, an American journalist working for Hearst in the area, published a book in October 1903 describing what he saw in Kishinev, which today is the capital of independent Moldova. The following is excerpted from his book:

Mayer Weissman had a very small store in one of the poorest Jewish quarters of the city.

He had lost an eye, by an accident when young. The mob attacked and demolished his little

grocery on Easter Sunday. He offered them all the money in his possession to spare his

life. It was a sum of sixty rubles. The leader took the money and then said: "Now, we want

your eye; you will never again look upon a Christian child." He implored them to kill him

instead of making him blind for life. They gouged out his eye with a sharpened stick, and

left him. Amidst sobs and suffering he told me his story in the Jewish Hospital.

Near the bed of poor blind Meyer Weissman was that of Joseph Shainovitch, whose

head had been battered with bludgeons, and the victim left for dead. He told me that it

was the same gang who killed his mother-in-law by driving nails through her eyes into

the brain. This story I refused to believe, thinking it might be born of some horrible

nightmare following the poor fellowís terrible experience, But from no less than six different

sources, one of them being a Christian doctor, I learned that the facts were as stated by

Joseph. Among other witnesses were the men who dug the unfortunate womanís grave.

Also in the hospital was a girl of about seventeen. Her head was covered with

bandages. She had been alone for three hours in the hands of a dozen men, who had

killed her father and mother, and they left her for dead. At the Rabbiís house I met

several more victims of the mobís nameless infamies. One was a girl of sixteen,

named Simme Zeytchik, very pretty, and childish-looking for her years. She told the

Rabbi that fifteen young ruffians had outraged her,

It is not astonishing that when some of the rioters were arrested they expressed

surprise, asking: Why were they were being arrested since "it had been permitted

to kill the Jews?" Indeed, in their complaints addressed by the sufferers to the

public prosecutor, they pointed to cases where the police encouraged the rioters

by the words: "Kill the Jews!"

shows bodies of some of the slaughtered. In all, 45 Jews were killed, 586 injured and countless women were raped and children tortured over the two-day period of April 19-20, 1903.

t was in this atmosphere throughout the Pale of Settlement that in 1903 Harry Shanas(14) would become the first of the family to escape the area and settle in Winnipeg. Now, he had to worry about his relatives who remained in Russia.

In 1903-05, the Russo-Japanese War took place, and once again the Russians looked for a scapegoat for a loss. More pogroms broke out, and they were much more systematic than the earlier ones. These new pogroms were directly sponsored by the government, which released the "Black Hundreds," an army of Cossaks who carried out large numbers of pogroms with the Czar's money (often referred to as "black money."). The attacks were mainly directed against the poor suburbs of Kiev, where the Shanas-Stracovsky and related families were living.

The aftermath of the first Russian Revolution of 1905 sparked even more anti-Semitism. In 1906, 1907 and 1912 Jewish men were eligible to vote in national elections for the first time, but this liberal attitude toward the Jews was short lived.

"Itís his fault!" A 1915 political cartoon by noted artist, Abel Pann, shows how all the troubles of Europe

were being blamed on the Jew, who had become the universal scapegoat. Pann left Ukraine in 1903, the

same year that Harry Shanas(14) left for Canada.

n 1915 mass numbers of Jews were evacuated from the front lines as the Pale was engulfed by World War I. The Pale came to an end as about a million Jewish refugees moved to urban centers (Including members of our family who moved from Brusilov to Kiev) as noted later on in this story.

The was abolished as a "temporary" war measure, and never re-instituted as the Russian Empire collapsed in 1917, and the Bolsheviks took power under Lenin and Trotsky. Between 1900 and the Holocaust more than half of the Jews in the area that constituted the Pale would move to the larger cities.

About three-quarters of the two million Russian Jews who would leave between 1881 and 1914 came to either the U.S. or Canada. Although official exit papers were required to leave Russia, many did it illegally. Members of the Shanas, Stracovsky and related families would continued to arrive there up to World War I.

Whether most Jews who left the "Old Country" did it to better their economic lives or to escape the pogroms is a matter of historic debate. Dr. Michael Stanislawski, Nathan J. Miller Professor of History at New York Cityís Columbia University, argues that it was the former. He maintains that despite the fact that popular legend (Fiddler on the Roof, etc) has it that the Jews came to escape the harsh pogroms, that wasnít the reason. Most who left, came from towns that didnít have pogroms. Nor was the reason for the great migration that Jews were trying to escape the draft. Everybody was trying to escape the draft, he notes. According to Stanislawski, Jews left simply because "there was no way for the growing Jewish population to feed itself."

ertainly this theory makes some sense with regard to the Shanas, Stracovsky and related families. Although one or two family members were known to be victims of pogroms, some of the most severe pogroms in the areas of their shtetls occurred after the family began arriving in Winnipeg. According to Dr. Jeffrey S. Gurock, Libby M. Klaperman Professor of Jewish History at New Yorkís Yeshiva University, pogroms were a major factor to those who were directly effected by them; "those who were in the wrong place at the wrong time." But what was more of a factor in the Jewish migration to the New World was "a hundred years of Czarist oppression."

In the case of the Shanas-Stracovsky families, the direct reasons for the migration to the new world were probably a combination of three factors: economic plight, continuous oppression of various types by government and individuals and the threat of pogroms always hanging over their heads.

In a taped 1982 "oral history" interview about his life, conducted just three months prior to his death at the age of 88, Alexander Abraham Shanas(1), the eldest son of Harry Shanas(14), recalled life in his shtetl of Kornin in 1903, the year his father left for Winnipeg:

Father had to struggle to make ends meet. Adding to the economic difficulties was the fact

that in 1903 the revolutionary movement had reached our district, causing strife and hardship to our population (the Jews of Kornin). In addition, there was the possibility of a pogrom to come. So at the end of 1903 father, with a group of about 10 other people from our district, left Russia and came to Winnipeg."

ith Harry, Moses and several other family members now safely in Canada, the anti-Semitism continued back in Ukrainian Russia for those family members who remained there. The 1917-21 Civil War between that followed the Russian Revolution evolved into a new wave of pogroms which resulted in massive bloodshed for Jews in the area that our families came from. In those areas, the White Army, including the Ukrainian army, was fighting the Red Army, which included the Bolsheviks. The losing Ukrainians, with their long history of anti-Semitism, needed scapegoats. There were major pogroms in the cities of Berdichev and Zhitomir in the family region in January-February, 1919, and in hundreds of shtetlach in the area. Soldiers in the White army raped and killed Jews as they came through the shtetls; those in the Red Army merely robbed them.

Ida Pepperman(42), the daughter of Clara (Chaykeh) [Alpert] Shanas(29) and Alexander (Alex) Alpert(40), recalled(in a 1998 interview her paternal grandmother telling her of an incident in which Idaís grandmother was hanging some clothes on a line outside with some other women. "Suddenly," according to Idaís recounting of her grandmotherís story, "a band of Cossacks rode up on horses, swords drawn, and cut the arms off one of the women."

The Shanas Shtetl of Kornin had pogroms on June 24, July 9 and August 31, 1919. By this time the core of the Shanas-Stracovsky and related families that were to be in the New World had already arrived in Winnipeg. What happened to all members of the families that remained in the area is unknown, although we know for sure that at least one relative, a brother of Moses Stracovsky(10) was killed in a pogrom. We also know that part of the Kimmelfeld, the family of my maternal grandmother, left the shtetl of Brusilov and moved to nearby Kiev, probably just before a major pogrom hit the town around Chanukah of 1919.

ccording to a description in The Crimson Book of Pogroms in Ukraine, 1919-20, written in Russian by Sergey Gusev-Orenburgskij, a young student named "Shainiss" from the shtetl of Belaya Tzerkov (about 50 miles south of Kiev) was killed on July 23, 1919. We don't know if he was related.

The Crimson Book describes the Kornin pogroms in some detail. The following are key points from a partial translation done by scholar Katerina Kronick in 1984:

Kornin was devastated in the pogroms. The goal was to eliminate every Jew, and a bounty of 1,000 rubles was offered for Jewish heads. The goal was reached, and no Jew survived. Men, women and elderly people were killed. The corpses laid around for a long time because nobody survived who would take care of them.

It is estimated that between 1917 and 1921 there were some 2,000 separate pogroms in which 250,000 Jews were killed and uncountable thousands upon thousands more were maimed, injured, or raped. After that many of the shtetls were abandoned, as Jews moved into the larger cities.

ews in Russia had taken an active part in the Russian Revolution of 1917. They hoped that the revolution would bring about a rebirth of Jewish culture and life that had been repressed for so many years. It didn't. For a while, when the pogroms settled down, Jews of the Soviet Union made some progress under the communist government, especially in the larger cities during the 1920s. But then as the government became more oppressive Jews -- like all Russians -- could only advance if they abandoned their religious practices.

By the end of 1919, the Bolsheviks had gained control of the area, and in 1920 most of Ukraine became part of the USSR. In 1925 Stalin was victorious over his political opponents and Trotsky was expelled.

In 1932 Stalin instituted the "collectivization" of agriculture throughout the Russian empire, and that, accompanied by a severe famine in Ukraine, resulted in the deaths by starvation of millions of Ukrainians. The families in Winnipeg would often send "care packages" to their relatives back in Ukraine. But around this period our Russian Jewish family in Winnipeg stopped hearing from their relatives back home. In essence, all contact was lost between the families in the Old and New worlds. In most cases that contact would be lost forever as World War II drew closer.

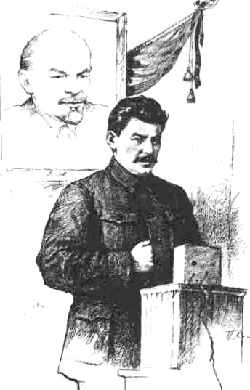

Once Joseph Stalin (seen with portrait of Lenin in background) came to power, all contact between our family in Russia and our family in Winnipeg would be lost.

n 1935 all Jewish schools in the Russian Empire were closed by Stalin. On November 1-2, 1939, the Soviet Union annexed the western Ukraine, which was formerly part of Poland. Before long, all Jewish institutions and organizations were abolished, and thousands of Jewish leaders and activists were exiled. Stalin, now thoroughly entrenched in power, had instituted a reign of terror in almost every aspect of Soviet life. Once again, the Jews suffered greatly. 1939 also marked the year of Stalin and Hitlerís "Non-Aggression Pact."

When the Nazis invaded the USSR on June 22, 1941, there were four million Jews living under the Soviet flag, most in the western part of the country. This included about 2.4 million in Ukraine's post -1939 borders. There were an estimated 140,000 Jews in Kiev; 153,200 in Odessa; 81,000 in Kharkov; 37,000 in Vitebsk; 28,000 in Zhitomir;

and 28,400 in Berdichev. These are all larger towns, around the four shtetles of the Shanas-Stracovsky and related families, for which there are records. By October, 1941 just about the entire Ukrainian republic was conquered. The invading armies received help from Ukrainian nationalist military units. Many Ukrainian nationals and church leaders welcomed the invading Germans as "liberators."

he entire Jewish populations of all these towns were virtually wiped out in the war. There were mass shootings done by killing squads, especially trained to wipe out large numbers of Jews; hangings and later, during the "Final Solution," mass gassings. The Jews of Zhitomir -- just 25 miles west of the Shanas-Stracovsky towns of Brusilov and Kornin -- become the first victims of the mass extermination process. By September 19, 1941, the city's entire Jewish population, then some 10,000 people, had been killed.

In the town of Belaya Tserkov, about 27 miles southeast of the Shanas shtetl of Popilnia, Several hundred Jewish adults and three truckloads of children were shot on August 19, 1941. Somehow 90 infants were not included, and on August 22 they were shot as a group by the Ukrainian police (whose deep-rooted anti-Semitism made them very happy to assist the conquering Germans).

In Berdichev, about 36 miles southwest of the Shanas-Stracovsky shtetl of Kornin, and not far from the other three family shtetls, the entire population of some 30,000 Jews (about half of the cityís total population) was shot. Some 10,000 men, women and children were shot in one day, September 5, 1941, at huge pits they were forced to dig about five miles south of Berdichev, near the village of Khazhin. On September 14, the remaining 20,000 -- mostly older men, and women, the sick, mothers, small children and infants -- were shot at ten pits at various locations just west of Berdichev. All this was done with the full help and cooperation of the Ukrainian police.

Throughout Ukraine hundreds of thousands of Jews and tens of thousands of other citizens suspected of being communists were murdered. Entire city populations were left to starve. Millions were put on forced labor. Most Jews still living at the time of the war in the four family shtetls of Brusilov, Kornin, Pavoloch and Popilnia just outside of Kiev, were exterminated.

On September 19, 1941, the city of Kiev fell to the Nazis. Some 60,000 of the 160,000 Jews in Kiev City were trapped. Another 100,000 escaped the town, but most probably were killed in the war. (We would`learn in 1995 that a good many of the Kimmelfelds escaped death by evacuating Kiev about a month before the Nazi invasion, and escaping to Alma-Alta, Kazakhstan, about 2,000 miles away, not far from the Chinese border (see Chapter XIII).

On September 29-30, 1941 about 33,000 of the Kievís Jews were brought to the nearby ravine of Babi Yar and machine gunned. The Babi Yar slaughter continued for months afterward, and ultimately over 100,000 Jews, Gypsies and Soviet prisoners of war were shot and dumped into the ravine. Among those known to have been killed at Babi Yar from our families were Frieda Gorstein(412), the daughter of Yirmiyahu (Yirmi) Gorstein(309). It was Yirmiís sister, Ghida Faiga Gorstein(275) who married Simcha Shanas(85), becoming the parents of Harry Shanas(14), the first to make it to Winnipeg.

On September 29-30, 1941 about 33,000 of the Kievís Jews were brought to the nearby ravine of Babi Yar and machine gunned. The Babi Yar slaughter continued for months afterward, and ultimately over 100,000 Jews, Gypsies and Soviet prisoners of war were shot and dumped into the ravine. Among those known to have been killed at Babi Yar from our families were Frieda Gorstein(412), the daughter of Yirmiyahu (Yirmi) Gorstein(309). It was Yirmiís sister, Ghida Faiga Gorstein(275) who married Simcha Shanas(85), becoming the parents of Harry Shanas(14), the first to make it to Winnipeg.

It was leaned as part of this family history research that members of our family were among

the tens of thousands killed in the mass executions of Babi Yar, then just outside of Kiev.

Also killed at Babi Yar were many in the family of Gregory Goldfarb(345), whose wife, Shifra [Goldfarb] Zaydenberg(344) was a descendent of the Kimmelfeld family, the family of my maternal grandmother.

Throughout Ukraine, Jews were held in ghettos, not knowing they were awaiting extermination. In all, an estimated 1.5 million Jews in the Soviet Union were murdered in the war between September, 1939 and June, 1945. About 800,000 of Ukraineís 1.5 million Jews were evacuated or escaped.

After the "liberation" of Ukraine (Kiev was liberated by Russiaís Red Army on November 6, 1943), many Jews tried to return home, and encountered fierce anti-Semitism. In Kiev it reached the level of a pogrom. So between 1945 and 1950 some 200,000 death camp survivors emigrated to Israel; 72,000 to the U.S. and 16,000 to Canada. Another 300,000 did return to the Soviet Union, many of them to Ukraine after the War. This included many of the members of the Kimmelfeld-Goldfarb family. It is estimated that by 1960 there were more than 200,000 Jews in Kiev and 14,000 more in the smaller towns of the Kiev district. Zhitomir had 15,800 in 1960; Berdichev had an estimated 15,000 in 1970. There were virtually no Jews living in the Shanas-Stracovsky and related families shtetls after the war.

eanwhile, under Communism, employment and religious discrimination was practiced on a large scale against the Jews. In 1948 Stalin launched a new anti-Semitic campaign, this one aimed at eradicating Jewish culture. Many Jewish writers and poets were executed after being charged with "espionage," "Zionism," or "Imperialism." After the war, the borders were closed and Jewish emigration in any meaningful numbers stopped until the fall of communism in 1989. Although not as tough as Stalin, anti-Semitic controls of a various nature continued through the years under Nikita Khruschev. In 1958, for example, author Boris Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for his novel, "Dr. Zhivago," but forced to decline the prize. The situation for Soviet Jews became even worse under Leonid Brezhnev and Alexei Kosygin, following Israelís 1967 victory over Soviet-allied Arab states.

The situation began to change a bit after the death of Brezhnev in 1982. By 1988 emigration to Israel began to increase, and picked up greatly in 1991 with the breakup of the Soviet Union into the Commonwealth of Independent States. It was in 1990 that Alexander Goldfarb(346), a decendent of the Kimmelfelds, and his family, would emigrate to Israel from Kiev. Four years later, in 1994, I was able to contact him, and a year later meet him in Israel Ė the meeting at which we proved that the Kimmelfeld-Stracovsky descendents in the western world still had relatives in the former Soviet Union. In July, 1997, I would go to Kiev to meet Alexanderís sister, Faina Grigorievna [Savenko] Goldfarb(107), and several of the Kimmelfeld relatives living in Ukraine. Earlier that year, in January, 1997, Alexander Goldfarb(346) and his family had emigrated to Los Angeles from Israel.

ccording to a Yeshiva University study, in 1990, just after the collapse of the Soviet Union, there were no organized educational opportunities to learn about Judaism. Ten years later, in the year 2000, the countries that comprised the former Soviet Union, with some two million Jews, had more than 300 Jewish kindergartens, Sunday schools and day schools. Some 50 universities were offering Jewish Studies courses and several had established full departments of Jewish Studies. Interestingly, a significant percentage of students majoring in Jewish Studies were not Jewish.

On March 22, 2000, the Jewish community of Kiev, re-opened its 102-year-old Central Synagogue, which had been used as a puppet theater during decades of Soviet rule. The synagogue had been built in 1898 at the time that Ukraineís massive Jewish migration to the western world was starting to grow, and closed down by communist officials in 1926. Renovation began in 1997, a few years after the collapse of communism. But, despite the renovation of the synagogue, and despite new religious and cultural freedoms, Ukraineís 500,000 Jewish population was shrinking rapidly with the start of the millennium Ė mainly because of emigration to Israel and the United States as well as intermarriage.

However the Jews who remained, including those family members I met with on my 1997 visit to the Old World, were now free to practice their religion after centuries of brutal anti-Semitism. In discussing it with them, they still considered their ancestors who had made it to Winnipeg the more fortunate ones.