The New Cemetery in Lodz

Contents

See also:

Background

The cemetery on

ul. Bracka and ul. Zmienna, the largest Jewish cemetery in Europe,

was created in 1892 when residents of the nearby neighborhood refused to

allow the expansion of the old cemetery on ul. Wesola,

containing over 3,000 graves. Izrael Poznanski donated the first 10.5 hectares

of land towards the establishment of a new cemetery. The

outbreak of a cholera epidemic in 1892 forced the Russian authorities to

give the final go ahead to establish the new cemetery. Thus, the first

people buried there in the winter of 1892 were approximately 700 cholera victims. In 1893, 1,139 people were buried at the new cemetery. From 1893

to 1896, the basic construction of the cemetery was completed under the

supervision of well-known architect Adolf Zeligson.

|

The Beit Tahara (Funeral

Home) was founded by Mina Dobrzynska Konsztat in 1896 and completed

in 1898. In 1900, the cemetery was greatly expanded by a purchase of land

from Albert Cukier and in 1913 other lands were added. In that year, houses

for cemetery workers and a wooden synagogue were built. The cemetery was

severely damaged during WWI and many buildings destroyed. Its renovation

was supported financially by factory owners. By 1925, the original wooden

fence surrounding the cemetery was replaced by the red brick wall that

still stands today. All tombstones in the cemetery face east. In the 19th

century, many were colorfully painted, traces of which can still be seen.

Right: Beit Tahara at the Lodz

Cemetery |

|

After the German occupation in 1939,

the cemetery became part of the eastern section of the enclosed Lodz ghetto.

A total of about 200,000 Jews were incarcerated in the ghetto. Between

1940 and 1944, approximately 43,000 burials took place in the spare part

of the cemetery that became known as the Pole Gettowe or Ghetto

Field. Many of those interred were victims of starvation, cold and

disease (especially typhus); they included Jews from Germany, Austria,

Czechoslovakia and Luxembourg, who were transported to the ghetto in 1941,

as well as Roma

(Gypsies) who died in the Gypsy Camp in the ghetto. The cemetery was the site of

mass executions of Jews, Roma and non-Jewish Poles: the

graves of the Polish scouts and soldiers of the Home Army are found

there. The Germans forbade the use of stone grave markers, so burial sites

were marked with metal bed frames or low cement posts. After the ghetto

was liquidated in August 1944, about 830 Jews were left as a clean-up crew.

They were forced to dig large holes for their own graves near the cemetery

wall. The Nazis did not have enough time to kill them, and the empty holes

have been left as a remembrance.

Right after WWII, Lodz became one

of the largest gathering places of Jewish survivors of concentration camps

and refugees from the U.S.S.R. This is the reason why so many graves from

the first post-war years can be found there. A

symbolic grave was constructed for 84

Jewish women from Lodz, from the Stutthof concentration camp, who were

murdered

Monument to the victims of the Lodz Ghetto |

by the Nazis in 1945 near Wejherowo. In 1956, a monument

in memory of the victims of the Lodz ghetto by Muszko was erected at the

cemetery. It features a smooth obelisk, a menorah (an important symbol

of the Jewish nation), and a broken oak tree with leaves stemming from

the tree (symbolizing death, especially death at a young age). Also in

1956, the city authorities widened a road that reduced the southwest area

of the cemetery. Tombstones were moved and remain in locations other than

the original ones. The cemetery deteriorated and was vandalized over the

following decades.

|

The first attempts to protect the

cemetery were made in the mid-1970s. In 1980, the cemetery was registered

as an historical site. In 1995, the city of Lodz and the Organization

of Former Residents of Lodz in Israel established the Monumentum

Iudaicum Lodzense Foundation

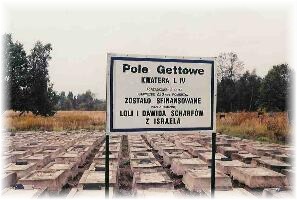

The Ghetto Field in the Lodz Cemetery, 1998. The

sign reads:

|

Pole

Gettowe, Kwatera

L IV

Porzadkowanie Oraz Ustawienie 250-CIU Pomników Zostalo

Sfinansowane przez Rodzinie

LOLI I DAWIDA

SCHARFÓW Z ISRAELA |

|

to preserve the cemetery and other remains

of Jewish culture in Lodz. In 1996, the World Restitution Organization

joined the foundation. In recent years, a project was begun to place low concrete markers

on the grave sites in the Ghetto Field. The Ghetto Field is marked by two

large Ohels -- a brick construction marking the graves of rabbis,

tzaddiks and spiritual masters of Chassidism -- covering the final resting

place of the rabbinical dynasty of Pabianice (see section "G-V" in

the cemetery plan) and the tzaddikim dynasty

from Sochaczew (see section "G-IV" in the

cemetery plan). Overgrown vegetation and moisture threaten the condition

of the tombstones and create a significant problem in negotiating one's

way through the cemetery. Recent efforts have focused on clearing vegetation

and leveling the ground, as well as restoration of specific tombstones

and mausoleums, the funeral home and the wall surrounding the cemetery.

Indexing of the Lodz Cemetery is in progress. To see the names

and locations of those already indexed, go to the website for

the Jewish Lodz Cemetery and see the

cemetery plan. You can search all the burial plots at one time

through

Steve Morse's One Step website. Indexing of the Lodz Cemetery is in progress. To see the names

and locations of those already indexed, go to the website for

the Jewish Lodz Cemetery and see the

cemetery plan. You can search all the burial plots at one time

through

Steve Morse's One Step website.

|

The cemetery contains approximately

180,000 graves, marked by approximately 65,000 tombstones, ohels and mausoleums,

many of which are of architectural significance.

|

One hundred of these have been declared historical monuments and are in

various stages of restoration. The mausoleum of Izrael

and Eleanora Poznanski is perhaps the largest Jewish tombstone in the

world and the only one decorated with mosaics. The Monumentum Iudaicum Lodzense Foundation, recently

initiated the idea to make the cemetery a UNESCO

World Heritage Site. As a result, it has now been formally tabled in

the Polish parliament by the Polish minister of culture. The present size

of the cemetery is 42.5 hectares. It continues to function as a Jewish

burial site.

|

Tombstones in the Lodz Cemetery, with the domed

Poznanski mausoleum visible in the background |

The International

Jewish Cemetery Project entries for the old and new cemeteries in Lodz contain

reports on the physical condition of these sites and additional information.

Facts obtained from: Przewodnik

po Cmentarzu Zydowskim w Lodzi (A Guide to the Jewish Cemetery in Lodz),

1997, Lodz City Office, A Guide to Jewish Lodz, 1994, by Jerzy Malenczyk,

and other sources.

Records of the Cemetery

The extant records of the new cemetery,

from 1892 to August 1944, are an excellent source of genealogical information.

By viewing the father's name of the deceased, family relationships may

be easily identified. After finding records of individuals in the LDS

microfilm of Lodz, their burial location in the cemetery records

may also be found, if the individual died in, or after, 1892. In some instances,

the cemetery records can supplement information found in the ghetto list,

Lodz-Names: List

of Ghetto Inhabitants, 1940-1944, by supplying the father's name

of those in the ghetto list and buried in the cemetery. Some ghetto victims

whose names are not found at all in Lodz-Names:

List of Ghetto Inhabitants, 1940-1944 are found in the cemetery

records. This is evidence that the published ghetto records are an incomplete

list of all Jews incarcerated in the ghetto. Limitations of the cemetery

records are the lack of maiden names of married women and, occasionally,

missing father's names.

These valuable records are held by

two entities: the Jewish community

of Lodz and the Organization

of Former Residents of Lodz in Israel. The best way to obtain information

from these entities is an on-site visit, either by yourself or your representative.

Be prepared to offer a donation along with your request.

The

Jewish Community of Lodz

Mr. Symcha Keller

Gmina Wyznaniowa Zydowska

ul. Pomorska 18

Lodz 90-201, Poland

Phone: 48-42-6320427

Fax: 48-42-6335156

Mr. Symcha Keller is the Secretary

of the Jewish Community of Lodz. He has a large card file of, one hopes,

all the burials in the large cemetery now in use. Each card gives, at minimum,

the name of the person, his or her last address, and the location of the

grave. He, as well as the caretaker at the cemetery itself, has a large

chart of the graves.

|

Tombstones in the Lodz Cemetery |

I visited

the cemetery in 1997. Once you get past the first several rows of graves,

which are on open ground, you enter a thicket, almost a jungle. The caretaker

put on hip boots before going there. Footing is precarious. Upheaval of

the ground here, and there, has thrown gravestones over. To find the grave

of one relative I had to keep reading headstones while the caretaker checked

against his chart. Back there, the alignment of the rows and columns is

not at all clear. At what had to be the grave site of my cousin, the stone

was lying on its face; we could not lift it.

- Arthur

S. Abramson

|

The

Organization of Former Residents of Lodz in Israel

158 Dizengoff Street

Tel Aviv 63461

Israel

Phone: 972-(0)3-524-1833

Fax: 972-(0)3-523-8126

This all volunteer group in Tel Aviv

maintains a database of those buried in the Lodz Jewish cemetery, between

approximately 1892 and the ghetto's liquidation in August 1944. This information

is printed in loose-leaf binders in alphabetical order. The burial list

includes an identification number, surname and first name(s), father's

name, age at death, date of death as year/month/day and exact site within

the cemetery and notes.

- Michael

J. Meshenberg

For more information, see:

Photos courtesy of Pawel B.

Dorman and Howard L. Rosen z"l

|